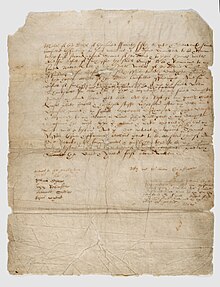

A devise is real property given by will.[1] A bequest is personal property given by will.[2] Today, the two words are often used interchangeably due to their combination in many wills as devise and bequeath, a legal doublet. The phrase give, devise, and bequeath, a legal triplet, has been used for centuries, including the will of William Shakespeare.

The word bequeath is a verb form for the act of making a bequest.[3]

Etymology

editBequest comes from Old English becwethan, "to declare or express in words" — cf. "quoth".

Interpretations

editPart of the process of probate involves interpreting the instructions in a will. Some wordings that define the scope of a bequest have specific interpretations. "All the estate I own" would involve all of the decedent's possessions at the moment of death.[4]

A conditional bequest is a bequest that will be granted only if a particular event has occurred by the time of its operation. For example, a testator might write in the will that "Mary will receive the house held in trust if she is married" or "if she has children," etc.

An executory bequest is a bequest that will be granted only if a particular event occurs in the future. For example, a testator might write in the will that "Mary will receive the house held in a trust set when she marries" or "when she has children".

In some jurisdictions a bequest can also be a deferred payment, as held in Wolder v. Commissioner, which will impact its tax status.

Explanations

editIn microeconomics, theorists have engaged the issue of bequest from the perspective of consumption theory, in which they seek to explain the phenomenon in terms of a bequest motive.

Oudh Bequest

editThe Oudh Bequest is a waqf[5] which led to the gradual transfer of more than six million rupees from the Indian kingdom of Oudh (Awadh) to the Shia holy cities of Najaf and Karbala between 1850 and 1903.[6] The bequest first reached the cities in 1850.[7] It was distributed by two mujtahids, one from each city. The British later gradually took over the bequest and its distribution; according to scholars, they intended to use it as a "power lever" to influence Iranian ulama and Shia.[8]

American tax law

editRecipients

editIn order to calculate a taxpayer's income tax obligation, the gross income of the taxpayer must be determined. Under Section 61 of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code gross income is "all income from whatever source derived".[9] On its face, the receipt of a bequest would seemingly fall within gross income and thus be subject to tax. However, in other sections of the code, exceptions are made for a variety of things that do not need to be included in gross income. Section 102(a) of the Code makes an exception for bequests stating that "Gross income does not include the value of property acquired by gift, bequest, or inheritance."[10] In general this means that the value or amount of the bequest does not need to be included in a taxpayer's gross income. This rule is not exclusive, however, and there are some exceptions under Section 102(b) of the code where the amount of value must be included.[10] There is great debate about whether or not bequests should be included in gross income and subject to income taxes; however, there has been some type of exclusion for bequests in every Federal Income Tax Act.[11]

Donors

editOne reason that the recipient of a bequest is usually not taxed on the bequest is because the donor may be taxed on it. Donors of bequests may be taxed through other mechanisms such as federal wealth transfer taxes.[11] Wealth Transfer taxes, however, are usually imposed against only the very wealthy.[11]

References

edit- ^ Devise

- ^ Black's Law Dictionary 8th ed, (West Group, 2004)

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bequest". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 761.

- ^ Law.com, Law Dictionary: all the estate I own

- ^ Algar, Hamid (January 1980). Religion and State in Iran, 1785–1906: The Role of the Ulama in the Qajar Period. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520041004. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ Litvak, Meir (1 January 2001). "Money, Religion, and Politics: The Oudh Bequest in Najaf and Karbala', 1850–1903". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 33 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1017/S0020743801001015. JSTOR 259477. S2CID 155865344.

- ^ Nakash, Yitzhak (16 February 2003). The Shi'is of Iraq. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691115753. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Litvak, Meir (1 January 2000). "A Failed Manipulation: The British, the Oudh Bequest and the Shī'ī 'Ulamā' of Najaf and Karbalā'". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 27 (1): 69–89. doi:10.1080/13530190050010994. JSTOR 826171. S2CID 153498972.

- ^ "US CODE: Title 26,61. Gross income defined". Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ^ a b "US CODE: Title 26,102. Gifts and inheritances". Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ^ a b c Samuel A. Donaldson (2007). Federal Income Taxation of Individuals: Cases, Problems and Materials, 2nd Edition, St. Paul: Thomson/West, 93