The black wildebeest or white-tailed gnu (Connochaetes gnou) is one of the two closely related wildebeest species. It is a member of the genus Connochaetes and family Bovidae. It was first described in 1780 by Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann. The black wildebeest is typically 170–220 cm (67–87 in) in head-and-body length, and the typical weight is 110–180 kg (240–400 lb). Males stand about 111–121 cm (44–48 in) at the shoulder, while the height of the females is 106–116 cm (42–46 in). The black wildebeest is characterised by its white, long, horse-like tail. It also has a dark brown to black coat and long, dark-coloured hair between its forelegs and under its belly.

| Black wildebeest Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene – present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Black wildebeest in Mountain Zebra National Park, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Alcelaphinae |

| Genus: | Connochaetes |

| Species: | C. gnou

|

| Binomial name | |

| Connochaetes gnou (Zimmermann, 1780)

| |

| |

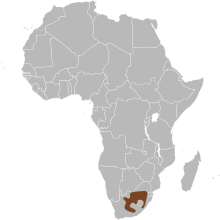

| Distribution range | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The black wildebeest is an herbivore, and almost the whole diet consists of grasses. Water is an essential requirement. The three distinct social groups are the female herds, the bachelor herds, and the territorial bulls. They are fast runners and communicate using a variety of visual and vocal communications. The primary breeding season for the black wildebeest is from February to April. A single calf is usually born after a gestational period of about 8 and 1/2 months. The calf remains with its mother until her next calf is born a year later. The black wildebeest inhabits open plains, grasslands, and karoo shrublands.

The natural populations of black wildebeest, endemic in the southern part of Africa, were almost completely exterminated in the 19th century, due to their reputation as pests and the value of their hides and meat, but the species has been reintroduced widely from captive specimens, both in private areas and nature reserves throughout most of Lesotho, Eswatini, and South Africa. The species has also been introduced outside its natural range in Namibia and Kenya.

Taxonomy and evolution

editThe scientific name of the black wildebeest is Connochaetes gnou. The animal is placed in the genus Connochaetes and family Bovidae and was first described by German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann in 1780.[3] He based his description on an article written by natural philosopher Jean-Nicolas-Sébastien Allamand in 1776.[2] The generic name Connochaetes derives from the Greek words κόννος, kónnos, "beard", and χαίτη, khaítē, "flowing hair", "mane".[4] The specific name gnou originates from the Khoikhoi name for these animals, gnou.[5] The common name "gnu" is also said to have originated from the Hottentot name t'gnu, which refers to the repeated calls of "ge-nu" by the bull in the mating season.[2] The black wildebeest was first discovered in the northern part of South Africa in the 1800s.[6]

The black wildebeest is currently included in the same genus as the blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus). This has not always been the case, and at one time the latter was placed under a genus of its own, Gorgon.[7] The black wildebeest lineage seems to have diverged from the blue wildebeest in the mid- to late Pleistocene, and became a distinct species around a million years ago.[8] This evolution is quite recent on a geologic time scale.[9]

Features necessary for defending a territory, such as the horns and broad-based skull of the modern black wildebeest, have been found in their fossil ancestors.[8] The earliest known fossil remains are in sedimentary rock in Cornelia in the Free State and date back about 800,000 years.[10] Fossils have also been reported from the Vaal River deposits, though whether or not they are as ancient as those found in Cornelia is unclear. Horns of the black wildebeest have been found in sand dunes near Hermanus in South Africa. This is far beyond the recorded range of the species and these animals may have migrated to that region from the karoo.[2]

Hybrids

editThe black wildebeest is known to hybridise with its taxonomically close relative, the blue wildebeest. Male black wildebeest have been reported to mate with female blue wildebeest and vice versa.[11] The differences in social behaviour and habitats have historically prevented interspecific hybridisation, but it may occur when they are both confined within the same area. The resulting offspring is usually fertile. A study of these hybrid animals at Spioenkop Dam Nature Reserve in South Africa revealed that many had disadvantageous abnormalities relating to their teeth, horns, and the wormian bones in the skull.[12] Another study reported an increase in the size of the hybrid as compared to either of its parents. In some animals, the auditory bullae are highly deformed, and in others, the radius and ulna are fused.[13]

Description

editBlack wildebeest are sexually dimorphic, with females being shorter and more slender than males.[2][14] The head-and-body length is typically between 170 and 220 cm (67 and 87 in). Males reach about 111 to 121 cm (44 to 48 in) at the shoulder, while females reach 106 to 116 cm (42 to 46 in).[15] Males typically weigh 140 to 157 kg (309 to 346 lb) and females 110 to 122 kg (243 to 269 lb). A distinguishing feature in both sexes is the tail, which is long and similar to that of a horse.[15] Its bright-white colour gives this animal the vernacular name of "white-tailed gnu",[16] and also distinguishes it from the blue wildebeest, which has a black tail. The length of the tail ranges from 80 to 100 cm (31 to 39 in).[15]

The black wildebeest has a dark brown or black coat, which is slightly paler in summer and coarser and shaggier in the winter. Calves are born with shaggy, fawn-coloured fur. Males are darker than females.[15] They have bushy and dark-tipped manes that, as in the blue wildebeest, stick up from the back of the neck. The hairs that compose this are white or cream-coloured with dark tips. On its muzzle and under its jaw, it has black bristly hair. It also has long, dark-coloured hair between its forelegs and under its belly. Other physical features include a thick neck, a plain back, and rather small and beady eyes.[14]

Both sexes have strong horns that curve forward, resembling hooks, which are up to 78 cm (31 in) long. The horns have a broad base in mature males, and are flattened to form a protective shield. In females, the horns are both shorter and narrower.[14] They become fully developed in females in the third year, while horns are fully grown in males aged four or five.[2] The black wildebeest normally has 13 thoracic vertebrae, though specimens with 14 have been reported, and this species shows a tendency for the thoracic region to become elongated.[2] Scent glands secrete a glutinous substance in front of the eyes, under the hair tufts, and on the forefeet. Females have two teats.[2][15] Apart from the difference in the appearance of the tail, the two species of wildebeests also differ in size and colour, with the black being smaller and darker than the blue.[17]

The black wildebeest can maintain its body temperature within a small range in spite of large fluctuations in external temperatures.[18] It shows well-developed orientation behaviour towards solar radiation, which helps it thrive in hot, and often shadeless, habitats.[19] The erythrocyte count is high at birth and increases till the age of 2–3 months, while in contrast, the leucocyte count is low at birth and falls throughout the animal's life. The neutrophil count is high at all ages. The haematocrit and haemoglobin content decreases till 20–30 days after birth. A peak in the content of all these haemological parameters occurs at the age of 2–3 months, after which the readings gradually decline, reaching their lowest values in the oldest individuals.[20] The presence of fast-twitch fibres and the ability of the muscles to use large amounts of oxygen help explain the rapid running speed of the black wildebeest and its high resistance to fatigue.[21] Individuals may live for about 20 years.[14]

Diseases and parasites

editThe black wildebeest is particularly susceptible to anthrax, and rare and widely scattered outbreaks have been recorded and have proved deadly.[22] Ataxia related to myelopathy and low copper concentrations in the liver have also been seen in the black wildebeest.[23] Heartwater (Ehrlichia ruminantium) is a tick-borne rickettsial disease that affects the black wildebeest, and as the blue wildebeest is fatally affected by rinderpest and foot-and-mouth disease, it is also likely to be susceptible to these. Malignant catarrhal fever is a fatal disease of domestic cattle caused by a gammaherpesvirus. Like the blue wildebeest, the black wildebeest seems to act as a reservoir for the virus and all animals are carriers, being persistently infected, but showing no symptoms. The virus is transmitted from mother to calf during the gestation period or soon after birth.[24]

Black wildebeest act as hosts to a number of external and internal parasites. A study of the animal in Karroid Mountainveld (Eastern Cape Province, South Africa) revealed the presence of all the larval stages of the nasal bot flies Oestrus variolosus and Gedoelstia hässleri. The first-instar larvae of G. hässleri were found in large numbers on the dura mater of wildebeest calves, specially between June and August, and these later migrated to the nasal passages.[25] Repeated outbreaks of mange (scab) have led to large-scale extinctions.[2] The first study of the protozoa in blue and black wildebeest showed the presence of 23 protozoan species in the rumen, with Diplodinium bubalidis and Ostracodinium damaliscus common in all the animals.[26]

Ecology and behavior

editBlack wildebeest are mainly active during the early morning and late afternoon, preferring to rest during the hottest part of the day.[27] The animals can run at speeds of 80 km/h (50 mph).[27] When a person approaches a herd to within a few hundred metres, the wildebeest snort and run a short distance before stopping and looking back, repeating this behaviour if further approached. They communicate with each other using pheromones detected by flehmen and several forms of vocal communication. One of these is a metallic snort or an echoing "hick", that can be heard up to 1.5 km (1 mi) away.[28] They are preyed on by the lion, spotted hyena, Cape hunting dog, leopard, cheetah, and Nile crocodile. Of these, the calves are targeted mainly by the hyenas, while lions attack the adults.[2]

The black wildebeest is a gregarious animal with a complex social structure comprising three distinct groups, the female herds consisting of adult females and their young, the bachelor herds consisting only of yearlings and older males, and territorial bulls. The number of females per herd is variable, generally ranging from 14 to 32,[14] but is highest in the densest populations[2] and also increases with forage density.[14] A strong attachment exists among members of the female herd, many of which are related to each other. Large herds often get divided into smaller groups. While small calves stay with their mothers, the older ones form groups of their own within the herd.[2] These herds have a social hierarchy,[2] and the females are rather aggressive towards others trying to join the group.[29] Young males are generally repelled by their mothers before the calving season starts. Separation of a young calf from its mother can be a major cause of calf mortality. While some male yearlings stay within the female herd, the others join a bachelor herd. These are usually loose associations, and unlike the female herds, the individuals are not much attached to each other.[2] Another difference between the female and bachelor herds is the lesser aggression on the part of the males. These bachelor herds move widely in the available habitat and act as a refuge for males that have been unsuccessful as territorial bulls, and also as a reserve for future breeding males.[2]

Mature bulls, generally more than 4 years old, set up their own territories through which female herds often pass. These territories are maintained throughout the year,[2] with animals usually separated by a distance around 100–400 m (330–1,310 ft), but this can vary according to the quality of the habitat. In favourable conditions, this distance is as little as 9 m (30 ft), but can be as large as 1,600 m (5,200 ft) in poor habitat.[27] Each bull has a patch of ground in the centre of his territory in which he regularly drops dung, and in which he performs acts of display. These include urinating, scraping, pawing, and rolling on the ground and thumping it with his horns - all of which demonstrate his prowess to other bulls.[2] An encounter between two bulls involves elaborate rituals. Estes coined the term "challenge ritual" to describe this behaviour for the blue wildebeest, but this is also applicable to the black wildebeest, owing to their close similarity in behavior.[2] The bulls approach each other with their heads lowered, resembling a grazing position (sometimes actually grazing). This is usually followed by movements such as standing in a reverse-parallel position, in which one male urinates and the opponent smells and performs flehmen, after which they may reverse the procedure. During this ritual or afterwards, the two can toss their horns at each other, circle one another, or even look away. Then begins the fight, which may be of low intensity (consisting of interlocking the horns and pushing each other in a standing position) or high intensity (consisting of their dropping to their knees and straining against each other powerfully, trying to remain in contact while their foreheads are nearly touching the ground). Threat displays such as shaking the head may also take place.[2]

Diet

editBlack wildebeest are predominantly grazers, preferring short grasses, but also feeding on other herbs and shrubs, especially when grass is scarce. Shrubs can comprise as much as 37% of the diet,[15] but grasses normally form more than 90%.[30] Water is essential,[31] though they can exist without drinking water every day.[32] The herds graze either in line or in loose groups, usually walking in single file when moving about. They are often accompanied by cattle egrets, which pick out and consume the insects hidden in their coats or disturbed by their movements.[2]

Before the arrival of Europeans in the area, wildebeest roamed widely, probably in relation to the arrival of the rains and the availability of good forage. They never made such extensive migrations as the blue wildebeest, but at one time, they crossed the Drakensberg Range, moving eastwards in autumn, searching for good pastures. Then they returned to the highvelds in the spring and moved towards the west, where sweet potato and karoo vegetation were abundant. They also moved from north to south as the sourgrass found north of the Vaal River matured and became unpalatable, the wildebeest only consuming young shoots of sourgrass.[2] Now, almost all black wildebeest are in reserves or on farms, and the extent of their movements is limited.[1]

In a study of the feeding activities of a number of female black wildebeest living in a shadeless habitat, they fed mostly at night. They were observed at regular intervals over a period of one year, and with an increase in temperature, the number of wildebeest feeding at night also increased. During cool weather, they lay down to rest, but in hotter conditions they rested while standing up.[18]

Reproduction

editMale black wildebeest reach sexual maturity at the age of 3 years, but may mature at a younger age in captivity. Females first come into estrus and breed as yearlings or as 2-year-olds.[2] They breed only once in a year.[14]

A dominant male black wildebeest has a harem of females and will not allow other males to mate with them. The breeding season occurs at the end of the rainy season and lasts a few weeks between February and April. When one of his females comes into estrus, the male concentrates on her and mates with her several times. Sexual behaviour by the male at this time includes stretching low, ears down, sniffing of the female's vulva, performing ritual urination, and touching his chin to the female's rump. At the same time, the female keeps her tail upwards (sometimes vertically) or swishes it across the face of the male. The pair usually separates after copulation, but the female occasionally follows her mate afterwards, touching his rump with her snout. During the breeding season, the male loses condition, as he spends little time grazing.[15] Males are known to mount other males.[33]

The gestation period lasts for about 8.5 months, after which a single calf is born. Females in labour do not move away from the female herd and repeatedly lie down and get up again. Births normally take place in areas with short grass when the cow is in the lying position. She stands up immediately afterwards, which causes the umbilical cord to break, and vigorously licks the calf and chews on the afterbirth. In spite of regional variations, around 80% of the females give birth to their calves within a period of 2–3 weeks after the onset of the rainy season - from mid-November to the end of December.[34] Seasonal breeding has also been reported among wildebeest in captivity in European zoos. Twin births have not been reported.[2]

The calf has a tawny, shaggy coat and weighs about 11 kg (24 lb). By the end of the fourth week, the four incisors have fully emerged and about the same time, two knob-like structures, the horn buds, appear on the head. These later develop into horns, which reach a length of 200–250 mm (8–10 in) by the fifth month and are well developed by the eighth month. The calf is able to stand and run shortly after birth, a period of great danger for animals in the wild. It is fed by its lactating mother for 6–8 months, begins nibbling on grass blades at 4 weeks, and remains with the mother until her next calf is born a year later.[14]

Distribution and habitat

editThe black wildebeest is native to southern Africa. Its historical range included South Africa, Eswatini, and Lesotho, but in the latter two countries, it was hunted to extinction in the 19th century. It has now been reintroduced there and also introduced to Namibia, where it has become well established.[1]

The black wildebeest inhabits open plains, grasslands, and karoo shrublands in both steep, mountainous regions and lower, undulating hills. The altitudes in these areas vary from 1,350–2,150 m (4,430–7,050 ft).[1] The herds are often migratory or nomadic, otherwise they may have regular home ranges of 1 km2 (11,000,000 sq ft).[27] Female herds roam in home ranges around 250 acres (100 ha; 0.39 sq mi) in size. In the past, black wildebeest occurred on temperate grasslands in highveld during the dry winter season and the arid karoo region during the rains. However, as a result of massive hunting of the animal for its hide, they vanished from their historical range, and are now largely limited to game farms and protected reserves in southern Africa.[32] In most reserves, the black wildebeest shares its habitat with the blesbok and the springbok.[2]

Threats and conservation

editWhere it lives alongside the blue wildebeest, the two species can hybridise, and this is regarded as a potential threat to the maintenance of the species.[1][11] The black wildebeest was once very numerous and was present in Southern Africa in vast herds, but by the end of the 19th century, it had nearly been hunted to extinction and fewer than 600 animals remained.[15] A small number of individuals was still present in game reserves and at zoos, and from these, the population was rescued.[1]

More than 18,000 individuals are now believed to remain, 7,000 of which are in Namibia, outside their natural range, and where they are farmed. Around 80% of the wildebeest occurs in private areas, while the other 20% is confined in protected areas. The population is now trending upward (particularly on private land) and for this reason the International Union for Conservation of Nature, in its Red List of Threatened Species, rates the black wildebeest as being of least concern Its introduction into Namibia has been a success and numbers have increased substantially there from 150 in 1982 to 7,000 in 1992.[1][14]

Uses and interaction with humans

editThe black wildebeest is depicted on the coat of arms of the Province of Natal in South Africa. Over the years, the South African authorities have issued stamps displaying the animal and the South African Mint has struck a 5-rand coin with a prancing black wildebeest.[2][35]

Though they are not present in their natural habitat in such large numbers today, black wildebeest were at one time the main herbivores in the ecosystem and the main prey item for large predators such as the lion. Now, they are economically important for human beings, as they are a major tourist attraction, and provide animal products such as leather and meat. The hide makes good-quality leather, and the flesh is coarse, dry, and rather tough.[27] Wildebeest meat is dried to make biltong, an important part of South African cuisine. The meat of females is more tender than that of males, and is at its best during the autumn season.[36] The wildebeest can provide 10 times as much meat as a Thomson's gazelle.[37] The silky, flowing tail is used to make fly-whisks or chowries.[27]

However, black wildebeest can also affect human beings negatively. Wild individuals can be competitors of commercial livestock and can transmit fatal diseases such as rinderpest, and cause epidemics among animals, particularly domestic cattle. They can also spread ticks, lungworms, tapeworms, flies, and paramphistome flukes.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Vrahimis, S.; Grobler, P.; Brink, J.; Viljoen, P.; Schulze, E. (2017). "Connochaetes gnou". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T5228A50184962. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T5228A50184962.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y von Richter, W. (1974). "Connochaetes gnou". Mammalian Species (50). The American Society of Mammalogists: 1–6.

- ^ Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 676. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Benirschke, K. "Wildebeest, Gnu". Comparative Placentation. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Gnu". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ a b Talbot, L. M.; Talbot, M. H. (1963). Wildlife Monographs:The Wildebeest in Western Masailand, East Africa. National Academies. pp. 20–31.

- ^ Corbet, S. W.; Robinson, T. J. (November–December 1991). "Genetic divergence in South African Wildebeest: comparative cytogenetics and analysis of mitochondrial DNA". The Journal of Heredity. 82 (6): 447–52. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111126. PMID 1795096.

- ^ a b Bassi, J. (2013). Pilot in the Wild: Flights of Conservation and Survival. South Africa: Jacana Media. pp. 116–8. ISBN 978-1-4314-0871-9.

- ^ Hilton-Barber, B.; Berger, L. R. (2004). Field Guide to the Cradle of Humankind : Sterkfontein, Swartkrans, Kromdraai & Environs World Heritage Site (2nd revised ed.). Cape Town: Struik. pp. 162–3. ISBN 177-0070-656.

- ^ Cordon, D.; Brink, J. S. (2007). "Trophic ecology of two savanna grazers, blue wildebeest Connochaetes taurinus and black wildebeest Connochaetes gnou" (PDF). European Journal of Wildlife Research. 53 (2): 90–99. doi:10.1007/s10344-006-0070-2. S2CID 26717246. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- ^ a b Grobler, J. P.; Rushworth, I.; Brink, J. S.; Bloomer, P.; Kotze, A.; Reilly, B.; Vrahimis, S. (5 August 2011). "Management of hybridization in an endemic species: decision making in the face of imperfect information in the case of the black wildebeest—Connochaetes gnou" (PDF). European Journal of Wildlife Research. 57 (5): 997–1006. doi:10.1007/s10344-011-0567-1. hdl:2263/19462. ISSN 1439-0574. S2CID 23964988.

- ^ Ackermann, R. R.; Brink, J. S.; Vrahimis, S.; De Klerk, B. (29 October 2010). "Hybrid wildebeest (Artiodactyla: Bovidae) provide further evidence for shared signatures of admixture in mammalian crania". South African Journal of Science. 106 (11/12): 1–4. doi:10.4102/sajs.v106i11/12.423. hdl:11427/27315.

- ^ De Klerk, B. (2008). "An osteological documentation of hybrid wildebeest and its bearing on black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou) evolution (doctoral dissertation)".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Lundrigan, B.; Bidlingmeyer, J. (2000). "Connochaetes gnou: black wildebeest". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Estes, R. D. (2004). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals : Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates (4. [Dr.]. ed.). Berkeley [u.a.]: University of California Press. pp. 156–8. ISBN 0-520-08085-8.

- ^ "Definition of WHITE-TAILED GNU". Merriam-Webster. 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- ^ Stewart, D. (2004). The Zebra's Stripes and Other African Animal Tales. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 186-8729-516.

- ^ a b Maloney, S. K.; Moss, G.; Cartmell, T.; Mitchell, D. (28 July 2005). "Alteration in diet activity patterns as a thermoregulatory strategy in black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou)". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 191 (11): 1055–64. doi:10.1007/s00359-005-0030-4. ISSN 1432-1351. PMID 16049700. S2CID 19400435.

- ^ Maloney, S. K.; Moss, G.; Mitchell, D. (2 August 2005). "Orientation to solar radiation in black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou)". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 191 (11): 1065–77. doi:10.1007/s00359-005-0031-3. ISSN 1432-1351. PMID 16075268. S2CID 106063.

- ^ Vahala, J.; Kase, F. (December 1993). "Age- and sex-related differences in haematological values of captive white-tailed gnu (Connochaetes gnou)". Comparative Haematology International. 3 (4): 220–224. doi:10.1007/BF02341969. ISSN 1433-2973. S2CID 32186518.

- ^ Kohn, T. A.; Curry, J. W.; Noakes, T. D. (9 November 2011). "Black wildebeest skeletal muscle exhibits high oxidative capacity and a high proportion of type IIx fibres". Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (23): 4041–7. doi:10.1242/jeb.061572. PMID 22071196.

- ^ Pienaar, U. de V. (1974). "Habitat-preference in South African antelope species and its significance in natural and artificial distribution patterns". Koedoe. 17 (1): 185–95. doi:10.4102/koedoe.v17i1.909.

- ^ Penrith, M. L.; Tustin, R. C.; Thornton, D. J.; Burdett, P. D. (June 1996). "Swayback in a blesbok (Damaliscus dorcas phillipsi) and a black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou)". Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 67 (2): 93–6. PMID 8765071.

- ^ Pretorius, J. A.; Oosthuizen, M. C.; Van Vuuren, M. (29 May 2008). "Gammaherpesvirus carrier status of black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou) in South Africa" (PDF). Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 79 (3): 136–41. doi:10.4102/jsava.v79i3.260. PMID 19244822.

- ^ Horak, I. G. (14 September 2005). "Parasites of domestic and wild animals in South Africa. XLVI. Oestrid fly larvae of sheep, goats, springbok and black wildebeest in the Eastern Cape Province". Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 72 (4): 315–20. doi:10.4102/ojvr.v72i4.188. PMID 16562735.

- ^ Booyse, D. G.; Dehority, B. A. (November 2012). "Protozoa and digestive tract parameters in Blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) and Black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou), with description of Entodinium taurinus n. sp". European Journal of Protistology. 48 (4): 283–9. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2012.04.004. hdl:2263/21516. PMID 22683066.

- ^ a b c d e f Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1184–6. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- ^ Estes, R. D. (1993). The Safari Companion : A Guide to Watching African Mammals, Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores and Primates. Halfway House: Russel Friedman Books. pp. 124–6. ISBN 0-9583223-3-3.

- ^ Huffman, B. "Connochaetes gnou, White-tailed gnu, Black wildebeest". Ultimate Ungulate. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ P., Apps (2000). Wild Ways : Field Guide to the Behaviour of Southern African Mammals (2nd ed.). Cape Town: Struik. p. 146. ISBN 186-8724-433.

- ^ Stuart, C.; Stuart, T. (2001). Field guide to mammals of southern Africa (3rd ed.). Cape Town: Struik. p. 202. ISBN 186-8725-375.

- ^ a b Estes, R. D. (2004). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals: Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates (4. [Dr.]. ed.). Berkeley [u.a.]: University of California Press. p. 133. ISBN 052-0080-858.

- ^ Gunda, M. R. (2010). The Bible and Homosexuality in Zimbabwe : A Socio-historical Analysis of the Political, Cultural and Christian Arguments in the Homosexual Public Debate with Special Reference to the Use of the Bible. Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-392-3507-740.

- ^ "Wildebeest". African Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ "Circulation Coins: Five Rand (R5)". South African Mint Company. 2011. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ Hoffman, L. C.; Van Schalkwyk, S.; Muller, N. (October 2009). "Effect of season and gender on the physical and chemical composition of black wildebeest meat". South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 39 (2): 170–4. doi:10.3957/056.039.0208. S2CID 83957360.

- ^ Schaller, G. B. (1976). The Serengeti Lion : A Study of Predator-prey Relations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 217. ISBN 022-6736-601.

External links

edit- Information at ITIS