This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2008) |

Constantinos A. Doxiadis[a] (14 May 1913 – 28 June 1975), often cited as C. A. Doxiadis, was a Greek architect and urban planner. During the 1960s, he was the lead architect and planner of Islamabad, which was to serve as the new capital city of Pakistan. He was later known as the father of ekistics, which concerns the multi-aspect science of human settlements.[2]

C. A. Doxiadis | |

|---|---|

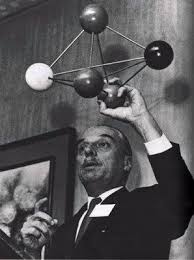

Doxiadis teaching the principles of ekistics | |

| Born | 14 May 1913 |

| Died | 28 June 1975 (aged 62) Athens, Greece |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Occupations |

|

| Children | Apostolos K. Doxiadis |

| Practice | Doxiadis Associates |

| Buildings | Teacher–Student Centre, University of Dhaka (Bangladesh) |

| Projects | Islamabad (Pakistan) |

Theories

editDoxiadis is the father of "ekistics", which concerns the science of human settlements, including regional, city, community planning and dwelling design.[2] The term was coined by Doxiadis in 1942 and a major incentive for the development of the science is the emergence of increasingly large and complex settlements, tending to regional conurbations and even to a worldwide city[dubious – discuss]. However, ekistics attempts to encompass all scales of human habitation and seeks to learn from the archaeological and historical record by looking not only at great cities, but, as much as possible, at the total settlement pattern.

Doxiadis also coined the term entopia, coming from the Greek words έν ("in") and τόπος ("place"). He quoted "What human beings need is not utopia ('no place') but entopia ('in place') a real city which they can build, a place which satisfies the dreamer and is acceptable to the scientist, a place where the projections of the artist and the builder merge."

Influence

editIn the 1960s and 1970s, urban planner and architect Constantinos Doxiadis authored books, studies, and reports including those regarding the growth potential of the Great Lakes Megalopolis.[3] At the peak of his popularity, in the 1960s, he addressed the US Congress on the future of American cities, his portrait illustrated the front cover of Time magazine, his company Doxiadis Associates was implementing large projects in housing, urban and regional development in more than 40 countries, his Computer Centre (UNIVAC-DACC) was at the cutting edge of the computer technology of his time and at his annual "Delos Symposium" the World Society of Ekistics attracted the worlds foremost thinkers and experts.

In Greece, he faced persistent suspicion and opposition and his recommendations were largely ignored. Having won two large contracts (National Regional Plan for Greece and Master Plan for Athens) from the Greek Junta he was criticised by competitors, after its fall in 1974, portrayed as a friend of the colonels. His visions for Athens airport to be constructed on the adjacent island of Makronissos, where political prisoners were held, together with a bridge, a rail link and a port at Lavrion were never realised.[citation needed]

His influence had already diminished at his death in 1975, as he was unable to speak for the last two years of his life, a victim of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).[4] His company Doxiadis Associates changed owners several times after his death, the heir to his computer company remained but without any links to planning or ekistics. The Delos Symposium was discontinued, and the World Society of Ekistics is today an obscure organisation.[citation needed]

Works about Doxiadis have appeared in the Museum of Brisbane, Milani Gallery, Brisbane and feature in the To Speak of Cities exhibition at the University of Queensland Art Museum.[5][6]

Works

editOne of his best-known town planning works is Islamabad. Designed as a new city it was fully realised, unlike many of his other proposals in already existing cities, where shifting political and economic forces did not allow full implementation of his plans. The plan for Islamabad, separates cars and people, allows easy and affordable access to public transport and utilities and permits low cost gradual expansion and growth without losing the human scale of his "communities".

In Riyadh, Doxiadis reoriented the city on a southwest-northeast axis, rendering "the planned city... similar to an immense mosque facing Mecca."[7] His work was also part of the architecture event in the art competition at the 1936 Summer Olympics.[8]

- The Sacrifices of Greece in the Second World War (exhibit, San Francisco City Hall, 1945)

- Sadr City of Baghdad, Iraq (1959)

- Master Plan of Islamabad, The capital of Pakistan;1960

- Master Plan for Skopje, city reconstruction plan following a major earthquake 1963.

- Teacher-Student Centre (TSC), University of Dhaka, Bangladesh; 1961

- Plan Doxiadis, Rio de Janeiro, 1965.

- Quaid-e-Azam Campus, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan, 1973.

Awards

editHis awards and decorations are as follows:[citation needed]

- Greek War Cross, for his services during the war of 1940-41 (1941)

- Order of the British Empire, for his activities in the Greek Resistance and for his collaboration with the Allied Forces, Middle East (1945)

- Order of the Cedar of Lebanon, for his contribution to the development of Lebanon (1958)

- Order of the Phoenix for his contribution to the development of Greece (1960)

- Sir Patrick Abercrombie Prize of the International Union of Architects (1963)

- Cali de Oro (Mexican Gold Medal) Award of the Society of Mexican Architects (1963)

- Award of Excellence, Industrial Designers Society of America (1965)

- Aspen Award for the Humanities (1966)

- Order of the Yugoslav Flag with Golden Wreath (1966)

Publications by Doxiadis

editBooks

edit- Dynapolis: The City of the Future. Doxiadis Associates. 1960. OL 16592889M.

- Doxiadis, Constantinos A. (1966). Emergence and Growth of an Urban Region: The Developing Urban Detroit Area. Detroit: Detroit Edison.

- Doxiadis, Constantinos A. (1966). Urban Renewal and the Future of the American City. Chicago: Public Administration Service.

- Doxiadis, Constantinos A. (1968). Ekistics: An Introduction to the Science of Human Settlements. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Doxiadis, Constantinos A. (1972). Architectural Space in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Doxiadis, Constantinos A. (1974). Anthropopolis: City for Human Development. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Doxiadis, Constantinos A.; Papaioannou, J.G. (1974). Ecumenopolis: The Inevitable City of the Future. Athens: Athens Center of Ekistics.

- Doxiadis, Constantinos A. (1975). Building Entopia. Athens: Athens Publishing Center.

- Doxiadis, Constantinos A. (1976). Action for Human Settlements. New York: W.W. Norton.

Journal articles

edit- Doxiadis, Constantinos A. (1965). "Islamabad, the creation of a new capital" (PDF). Town Planning Review. 36 (1): 1. doi:10.3828/tpr.36.1.f4148303n72753nm. S2CID 147532909.

- Doxiadis, Constantinos A. (1967). "On Linear Cities". Town Planning Review. 38 (1): 35. doi:10.3828/tpr.38.1.70733287173p06k8.

- Doxiadis, Constantinos A. (1968). "Man's Movement and His City". Science. 162 (3851): 326–334. Bibcode:1968Sci...162..326D. doi:10.1126/science.162.3851.326. PMID 17836649.

Publications on Doxiadis

edit- Kyrtsis, Alexandros-Andreas (2006). Constantinos A. Doxiadis: Texts, Design Drawings, Settlements. Athens: Ikaros

- Tsiambaos, Kostas (2018). From Doxiadis' Theory to Pikionis' Work: Reflections of Antiquity in Modern Architecture. London & New York: Routledge.

- Amygdalou, K., Kritikos, C. G., Tsiambaos, K. (2018). The Future as a Project: Doxiadis in Skopje. Athens: Hellenic Institute of Architecture.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Αποστόλου Δοξιάδης (pronounced [konstanˈdinos apoˈstolu ðoksiˈaðis]); also spelled Konstantinos.

References

edit- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (June 29, 1975). "Constantinos Doxiadis, City Planner, Is Dead at 62". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ a b Doxiadis, Constantinos Apostolos (1968). Ekistics: An Introduction to the Science of Human Settlements. Oxford University Press. OCLC 441332859.

- ^ "Cities: Capital for the New Megalopolis". Time. November 4, 1966. Retrieved on July 16, 2010.

- ^ Biographical Note, Doxiadis.org. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- ^ Brown, Phil (March 18–24, 2020). "Bold type". Brisbane News. 1267: 15.

- ^ The University of Queensland (2020). "Window commission sparks conversations about future cities". UQ News. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- ^ Menoret, Pascal (2014). Joyriding in Riyadh: Oil, Urbanism, and Road Revolt. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University. p. 69.

- ^ "Constantinos Apostolou Doxiadis". Olympedia. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

External links

edit- Doxiadis Foundation

- Center for Spatially Integrated Social Science

- An arieal view of a portion of Islamabad whose planning Doxiadis was involved with.

- Doxiadis on YouTube

- Doxiadis Associates

·