This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2014) |

The copperbelly water snake or copperbelly (Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta) is a subspecies of nonvenomous colubrid snake endemic to the Central United States.

| Copperbelly water snake | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Genus: | Nerodia |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | N. e. neglecta

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta (Conant, 1949)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

editCopperbelly water snakes have a solid dark (usually black but bluish and brown) back with a bright orange-red belly. They grow to a total length of 3 to 5 feet (91 to 152 cm). They are not venomous.

The longest total length on record is 65.5 inches (166 cm) for a specimen from the northern edge of their range.

Newborn copperbellies are 6 inches (15 cm) in total length, and in a year are about 18 inches (46 cm) in total length. They are patterned with two-toned, reddish-brown, saddle-like crossbanding with reddish-orange chins and lips. Their bellies are light orange. They are cryptic, camouflaged, secretive and hardly ever seen.

Habitat

editCopperbellies live in lowland swamps or other warm, quiet waters.

Lowland and some upland woods are almost always part of the swamp habitat. Recent studies have shown that at least 500 acres (200 ha) of more or less continuous swamp-forest habitat is necessary to sustain a viable population over time.

Vernal wetlands are necessary and frequently used by copperbellies in the spring through June, because of prey species' reproduction and growth.

Permanent, vegetated, shallow-edged wetlands are an important part of the habitat, but less so than vernal wetlands. A mix/matrix of both types within continuous swamp-forest and woodlots may be ideal for sustaining all age/size classes.

Crushing tiles to restore ponds in farm country enhances the habitat in case of drought, but keep Spring temporary swamps, regardless of size, that normally dry up in mid-late summer, as they are crucial to the habitat and associated flora and fauna.

Upland woods and slightly-elevated lowland chimney crayfish (Cambarus diogenes) burrows are used as winter hibernation sites. Barns and other outbuildings are also used.

Reproduction

editYoung snakes are born in the fall near or in the winter hibernation site. The average litter size is 18 young. The largest brood on record is 38 young born, in the northern part of their range.

Diet and feeding behavior

editThe snakes feed on frogs, tadpoles, salamanders, small fish, and maybe crayfish (crawdads).

Adults have been observed hunting in small groups, although this behavior is rarely seen.

An entire colony of all age/size classes has once been observed just underwater, foraging together in the shallows of a small woodland shrub swamp, their heads moving back and forth with mouths open, even along with a few common water snakes. They were apparently foraging for tadpoles.

Peak foraging times are 900–1300 hrs with a secondary, smaller peak between 1700–1900 hrs, depending on weather conditions. Nocturnal foraging has been observed in the southern part of the range, and after hot, humid summer days in the northern sector.

Prey species are caught in water and on land, often far from wetlands. The snakes find food in the woods after the late spring rains, especially if there is a high water table, cover items and chimney crayfish burrows.

Rivers, farm ditches, small streams, rocky areas and any fast-moving waters are avoided. Adjacent ditches and streams are often used, especially if enhanced by beaver and muskrat activity.

Geographic range and conservation status

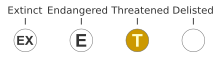

editThe population of copperbelly water snakes that lives in southern Michigan, northeastern Indiana (north of 40 degrees latitude in that state), and northwestern Ohio has been listed as threatened by the US Fish And Wildlife Service (USFWS). They are listed as endangered by the states of Michigan, Ohio and Indiana. Another population of these snakes lives in southwestern Indiana and adjacent Illinois and Kentucky, and southeastern Indiana. That population is not listed as threatened by the USFWS, but is protected by conservation agreements with State Departments of Natural Resources, various other State and Federal agencies, and coal companies.

Threats

editHabitat loss or degradation

editThese snakes have declined mainly because of the drainage, pollution, loss and filling over of their lowland swamp habitat and clearing of adjacent upland woods where they spend the winter (hibernation sites).

Collection

editCopperbelly water snakes are collected fairly regularly because of their rarity, large size, unique color, and value in the pet trade. Under the Endangered Species Act, collection is illegal without a permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Predation

editDuring migration, they are vulnerable to predation, especially when their migration routes are interrupted by cleared areas such as roads, mowed areas, and farmlands.

Efforts to prevent extinction

editListing

editThe copperbelly water snake was added to the U.S. List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants on February 28, 1997. The population that was listed as threatened occurs in southern Michigan, northeastern Indiana, and northwestern Ohio. The population that occurs in southern Illinois, southern Indiana, and western Kentucky was not listed but has been protected by conservation agreements with coal companies and other developers.

Recovery plan

editIn September 2007, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service completed a draft recovery plan that describes and prioritizes actions needed to conserve this subspecies.

Research

editResearchers are and will continue monitoring and surveying the copperbelly water snake to find current population status and the best ways to continue enhancing and managing for the snake and its habitat.

Law enforcement will be regularly on-site to prevent any collection, harassment and disturbance of this species and habitats. If any of these activities are found, legal action, including arrests and citations, will ensue.

All radiotracking and other invasive studies have been done 1987–2006, with all necessary baseline data gained. There is no longer a reason or need to continue with that disruptive practice.

Observing and monitoring copperbellies in the wild and their habitats should continue, as well as expanding and securing existing, confirmed habitats.

Habitat protection and management

editWhere possible, the snake's habitat (lowland swamps and adjacent upland woods) will be protected and improved. Endangered Species Act grants have funded habitat management on private lands that support copperbellies in Indiana and Michigan.

Captive breeding and release

editIn 2022, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service partnered with the Toledo Zoo to begin a captive propagation and release program.[3]

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ "Copperbelly water snake (Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Pruitt, Scott; Szymanski, Jennifer (29 January 1997). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Determination of Threatened Status for the Northern Population of the Copperbelly Water Snake". Federal Register. 62 (19): 4183–4192. 62 FR 4183

- ^ Wagner, Ryan (20 February 2023) [Originally published 14 February 2023]. "'They aren't mean and they aren't trying to get you': saving the copperbelly water snake". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

Further reading

edit- Conant, R. (1949). Two New Races of Natrix erythrogaster. Copeia. (1):1-15.

- Conant, R. (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Second Edition. Houghton Mifflin. Boston. xii + 429 pp. ISBN 0-395-19977-8 (paperback). (Natrix erythrogaster neglecta, pp. 143 + Map 103.)

- Smith, H.M., and E.D. Brodie, Jr. (2001). Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. Golden Press. New York. 240 pp. ISBN 0-307-13666-3 (paperback). (Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta, p. 154.)

- Wright, A.H., and A.A. Wright. (1957). Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada. Comstock. Ithaca and London. 1,105 pp. (in 2 volumes) (Natrix erythrogaster neglecta, pp. 484–486 + Map 39. on p. 478.)

External links

edit- Copperbelly Water Snake, Reptiles and Amphibians of Iowa