The Corsican Republic (Italian: Repubblica Corsa) was a short-lived state on the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean Sea. It was proclaimed in July 1755 by Pasquale Paoli, who was seeking independence from the Republic of Genoa. Paoli created the Corsican Constitution, which was the first constitution written in the Italian language. The text included various Enlightenment principles, including female suffrage,[1] later revoked by the Kingdom of France when the island was taken over in 1769. The republic created an administration and justice system, and founded an army.

Corsican Republic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1755–1769 | |||||||||

| Motto: Amici e non di ventura (English: Friends, and not by mere accident) | |||||||||

| Anthem: Dio vi salvi Regina ("God save you Queen") | |||||||||

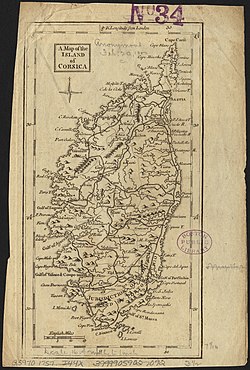

Corsica in 1757 | |||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||||

| Capital | Corte | ||||||||

| Official languages | Italian | ||||||||

| Common languages | Corsican | ||||||||

| Government | Modified parliamentary constitutional republic

| ||||||||

| General | |||||||||

• 1755–1769 | Pasquale Paoli | ||||||||

| Legislature | General Diet | ||||||||

| Historical era | Age of Enlightenment | ||||||||

• Independence declared | July 1755 | ||||||||

| 18 November 1755 | |||||||||

| 15 May 1768 | |||||||||

| 8–9 October 1768 | |||||||||

| 9 May 1769 | |||||||||

| Currency | Soldo | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | France ∟ Corsica | ||||||||

Foundation

editAfter a series of successful actions, Pasquale Paoli drove the Genoese from the whole island except for a few coastal towns. He then set to work re-organizing the government, introducing many reforms. He founded a university at Corte and created a short-lived "Order of Saint-Devote" in 1757 in honour of the patron saint of the island, Saint Devota.[2]

The Republic minted its own coins at Murato in 1761, imprinted with the Moor's Head, the traditional symbol of Corsica.

Paoli's ideas of independence, democracy and liberty gained support from such philosophers as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, Raynal, and Mably.[3] The publication in 1768 of An Account of Corsica by James Boswell made Paoli famous throughout Europe. Diplomatic recognition was extended to Corsica by the Bey of Tunis.[4]

Pasquale Paoli and Italian irredentism

editThe Corsican revolutionary Pasquale Paoli was called "the precursor of Italian irredentism" by Niccolò Tommaseo because he was the first to promote the Italian language and socio-culture (the main characteristics of Italian irredentism) in his island; Paoli wanted the Italian language to be the official language of the newly founded Corsican Republic.

Pasquale Paoli's appeal in 1768 against the French invader said:

We are Corsicans by birth and sentiment, but first of all we feel Italian by language, origins, customs, traditions; and Italians are all brothers and united in the face of history and in the face of God ... As Corsicans we wish to be neither slaves nor "rebels" and as Italians we have the right to deal as equals with the other Italian brothers ... Either we shall be free or we shall be nothing... Either we shall win or we shall die (against the French), weapons in hand ... The war against France is right and holy as the name of God is holy and right, and here on our mountains will appear for Italy the sun of liberty

— Pasquale Paoli[5]

Paoli was sympathetic to Italian culture and regarded his own native language as an Italian dialect (Corsican is an Italo-Dalmatian tongue closely related to Tuscan). Paoli's Corsican Constitution of 1755 was written in Italian and the short-lived university he founded in the city of Corte in 1765 used Italian as the official language.

Government

editAccording to the constitution, the legislature, the Corsican Diet (or Consulta Generale), composed of over 300 members, met once a year on call of the head of state and was composed of delegates elected by acclamation from each parish for three-year terms. The Diet enacted laws, regulated taxation, and determined national policy. Executive powers were handled by the Council of State, elected by the Diet initially for life and which met twice a year, in the absence of which powers were held by the General (chair of the Council) or in their absence, by the President General or by one president from each of the three magistracies of the Council (rotated monthly), one councilor (rotated between the three magistracies every 10 days), and the secretary of state. The General was elected by the Council and had to maintain their confidence in order to remain in the position, although there were no term limits.[6] The General also had a right to summon particular congresses on specific issues separate from the Diet. In the council, two-thirds of its members were to come from Deçà des Monts, while the remainder were to come from Delà des Monts. The members were also split into two tiers: 36 first class Presidents, and 108 second class Councillors. The Council was divided into three magistracies: the Chamber of Justice (in charge of political affairs and the most serious criminal cases), the Chamber of War (in charge of military affairs), and the Chamber of Finance (in charge of economic affairs). Petitions made to the Council were addressed to the General, who according to importance, passed them to the applicable magistracy. From there, once studied, it would pass to the full Council for a vote. The head of the Council received two votes while other members received one. In the case of a tie, the secretary of state would vote to break it.

Other than the most serious crimes, other business was delegated to various tribunals. The chief civil court, the Rota Civile (from 1763 also entrusted with criminal cases), was composed of three doctors of law nominated for life by the Council. Provincial Magistratures were also established over time, able to judge minor criminal and civil offences. Minor civil cases were handled by the local judge in each of the 68 pieve (traditional administrative divisions). The Sindicato was a body that enabled the Diet to scrutinize the conduct of magistrates and officials except those from the Junta of War, being composed of the President of the Council and four members elected by the Diet. The Junta of War was in times of crisis authorized to condemn to prison and corporal punishment, and to confiscate and/or destroy property. It was able to mobilize local militias to enforce its sentences. It could also impose the death penalty in some cases.[6]

Suffrage was extended to all men over the age of 25,[7][8] and those men over the age of 35 could become members of the Council. Traditionally, women had always voted in village elections for podestà (i.e. village elders) and other local officials,[9] and it has been claimed that they also voted in national elections under the Republic if they were head of the family.[10]

Modifications

editIn 1758, the Diet reduced the Council from over 100 to 18 members (each of which had to live in Corte), and limited each of their terms to six months. In 1764 the number of Council members was reduced again to 9, each elected for a year.

From 1763, members of the clergy were allowed to send around 137 members to the Diet, and their influence grew such that by the following year the elected speaker of the diet until the dissolution of the republic was always a member of the clergy. Prior to 1763, members of the clergy were not allowed (by legislation) to be judged by canon law, and de facto were not allowed to give asylum to criminals.

In December 1763, the Diet passed legislation modifying the method of election of its members, where a reduced 68 members were to be indirectly elected. In this legislation, the number of clerical members were unchanged, as was the recently introduced practice of allowing the head of state to invite others to participate in the Diet. However, this legislation was never respected, de facto continuing under the old system. The following year elected members of the diet were made to be equipped with an notarial affidavit, stating they also had a right to, with other members of the pieve, elect one or more of themselves to represent the pieve as a whole, allowing the election of more than one person to represent a pieve.

In 1764, the Council of State was granted a suspensive veto, allowing them to suspend a resolution voted on by the Diet until it gave its motives for refusal, after which the Diet had an opportunity to reconsider and pass it again with no opportunity for a veto. In the sane session, resolutions were changed such that they required a two-thirds majority to be passed, although those that gained at least 50% support were allowed to be brought up again in the same session (while those that did not were not allowed, and could only be re-introduced in a future session with the consent of the Council).

In 1766, another attempt was made to change the method of election in each parish for its Diet representative(s), where he "was to be elected from a choice of three candidates proposed by the Podestats and 'Fathers of the Commune'; he had to win a two-thirds majority. Only heads of families had the right to vote. If none of the three won the required majority, another election was to take place. In this case, candidates were to be proposed by the heads of families. Three were to be selected by majority vote in a primary election; one of the three was to be elected in a secondary election by a two-thirds majority. If none of them won this majority, the parish forfeited its representation in that session of the Diet." This attempted change, similar to the prior one attempted in 1763, was seldom followed.[6]

French invasion

editIn 1767, Corsica took the island of Capraia from the Genoese who, one year later, despairing of ever being able to control Corsica again, sold their claim to the Kingdom of France with the Treaty of Versailles. France invaded Corsica the same year, with Paoli's forces fighting to keep the republic intact. However, in May 1769, at the Battle of Ponte Novu they were defeated by vastly superior forces commanded by the Comte de Vaux, and obliged to take refuge in the Kingdom of Great Britain.

French control was consolidated over the island, and in 1770 it became a province of France. Under France, the use of Corsican (a regional language closely related to Italian) has gradually declined in favour of the standard French language. Italian was the official language of Corsica until 1859.[11]

Aftermath

editThe fall of Corsica to the French was poorly received by many in Great Britain, which was Corsica's main ally and sponsor. It was seen as a failure of the Grafton Ministry that Corsica had been "lost", as it was regarded as vital to the interests of Britain in that part of the Mediterranean.[12] The Corsican Crisis severely weakened the Grafton Ministry, contributing to its ultimate downfall. A number of exiled Corsicans fought on the British side during the American Revolutionary War, serving with particular distinction during the Great Siege of Gibraltar in 1782.

Conversely, at the beginning of the same war, the New York militia later named Hearts of Oak - whose membership included Alexander Hamilton and other students at New York's King's College (now Columbia University) - originally called themselves "The Corsicans", evidently considering the Corsican Republic as a model to be emulated in America.[citation needed]

The aspiration for Corsican independence, along with many of the democratic principles of the Corsican Republic, were revived by Paoli in the Anglo-Corsican Kingdom of 1794–1796. On that occasion, British naval and land forces were deployed in defence of the island; however, their efforts failed and the French regained control.

To this day, some Corsican separatists, such as the (now-disbanded) Armata Corsa, advocate the restoration of the island's republic.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Lucien Felli, "La renaissance du Paolisme". M. Bartoli, Pasquale Paoli, père de la patrie corse, Albatros, 1974, p. 29. "Il est un point où le caractère précurseur des institutions paolines est particulièrement accusé, c'est celui du suffrage en ce qu'il était entendu de manière très large. Il prévoyait en effet le vote des femmes qui, à l'époque, ne votaient pas en France."

- ^ "The Church of St Devote of Monaco". www.gouv.mc. Archived from the original on 2009-02-21.

- ^ Scales, Len; Oliver Zimmer (2005). Power and the Nation in European History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 289. ISBN 0-521-84580-7.

- ^ Thrasher, Peter Adam (1970). Pasquale Paoli: An Enlightened Hero 1725-1807. Hamden, CT: Archon Books. p. 117. ISBN 0-208-01031-9.

- ^ N. Tommaseo. "Lettere di Pasquale de Paoli" (in Archivio storico italiano, 1st series, vol. XI).

- ^ a b c Carrington, Dorothy (1973). "The Corsican Constitution of Pasquale Paoli (1755-1769)". The English Historical Review. 88 (348): 481–503. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXVIII.CCCXLVIII.481. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 564654.

- ^ Gregory, Desmond (1985). The ungovernable rock: a history of the Anglo-Corsican Kingdom and its role in Britain's Mediterranean strategy during the Revolutionary War, 1793-1797. London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-8386-3225-4.

- ^ Gama Sosa, Michele (2021-06-21). "THE HEROIC STORY OF THE ISLAND THAT INSPIRED THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION". Grunge. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

- ^ Gregory, Desmond (1985). The ungovernable rock: a history of the Anglo-Corsican Kingdom and its role in Britain's Mediterranean strategy during the Revolutionary War, 1793-1797. London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-8386-3225-4.

- ^ Felli, Lucien (1974). "La renaissance du Paolisme". In Bartoli, M (ed.). Pasquale Paoli, père de la patrie corse. Paris: Albatros. p. 29.

Il est un point où le caractère précurseur des institutions paolines est particulièrement accusé, c'est celui du suffrage en ce qu'il était entendu de manière très large. Il prévoyait en effet le vote des femmes qui, à l'époque, ne votaient pas en France.

- ^ Abalain, Hervé, (2007) Le français et les langues historiques de la France, Éditions Jean-Paul Gisserot, p.113

- ^ Simms, Brendan (2008). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, 1714-1783. London: Penguin Books. p. 663. ISBN 978-0-14-028984-8.

External links

edit