The Royal National Theatre of Great Britain,[1] commonly known as the National Theatre (NT) within the UK and as the National Theatre of Great Britain internationally,[2][3] is a performing arts venue and associated theatre company located in London, England. The theatre was founded by the actor Laurence Olivier in 1963, and many well-known actors have performed with it since.

The National Theatre from Waterloo Bridge | |

| Former names | National Theatre Company (while based at the Old Vic from 1963) |

|---|---|

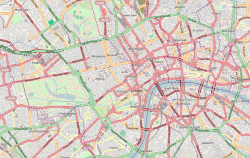

| Address | Upper Ground, South Bank London England |

| Coordinates | 51°30′26″N 0°06′51″W / 51.5071°N 0.1141°W |

| Public transit | |

| Designation | Grade II* |

| Type | National theatre |

| Capacity |

|

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1976 (building) |

| Architect |

|

| Website | |

| nationaltheatre | |

The company was based at The Old Vic theatre in Waterloo until 1976. The current building is located next to the Thames in the South Bank area of central London. In addition to performances at the National Theatre building, the National Theatre tours productions at theatres across the United Kingdom.[4] The theatre has transferred numerous productions to Broadway and toured some as far as China, Australia and New Zealand. However, touring productions to European cities was suspended in February 2021 over concerns about uncertainty over work permits, additional costs and delays because of Brexit.[5] Permission to add the "Royal" prefix to the name of the theatre was given in 1988,[6] but the full title is rarely used. The theatre presents a varied programme, including Shakespeare, other international classic drama, and new plays by contemporary playwrights. Each auditorium in the theatre can run up to three shows in repertoire, thus further widening the number of plays which can be put on during any one season. However, the post-2020 covid repertoire model became straight runs, required by the imperatives of greater resource efficiency and financial constraint coupled with the preference (and competition for the availability) of creatives working across stage and screen, thus bringing it in line with that of most theatres.

In June 2009, the theatre began National Theatre Live (NT Live), a programme of simulcasts of live productions to cinemas, first in the United Kingdom and then internationally. The programme began with a production of Phèdre, starring Helen Mirren, which was screened live in 70 cinemas across the UK. NT Live productions have since been broadcast to over 2,500 venues in 60 countries around the world. In November 2020, National Theatre at Home, a video on demand streaming service, specifically created for National Theatre Live recordings, was introduced. Videos of plays are added every month, and can be "rented" for temporary viewing, or unlimited recordings can be watched through a monthly or yearly subscription programme.[7][8]

The NT had an annual turnover of approximately £105 million in 2015–16, of which earned income made up 75% (58% from ticket sales, 5% from NT Live and Digital, and 12% from commercial revenue such as in the restaurants, bars, bookshop, etc.). Support from Arts Council England provided 17% of income, 1% from Learning and Participation activity, and the remaining 9% came from a mixture of companies, individuals, trusts and foundations.[9]

Origins

editIn 1847, a critic using the pseudonym Dramaticus published a pamphlet[10] describing the parlous state of British theatre. Production of serious plays was restricted to the patent theatres, and new plays were subjected to censorship by the Lord Chamberlain's Office. At the same time, there was a burgeoning theatre sector featuring a diet of low melodrama and musical burlesque; but critics described British theatre as driven by commercialism and a "star" system. There was a demand to commemorate serious theatre, with the "Shakespeare Committee" purchasing the playwright's birthplace for the nation demonstrating a recognition of the importance of "serious drama". The following year saw more pamphlets on a demand for a National Theatre from London publisher Effingham William Wilson.[11] The situation continued, with a renewed call every decade for a National Theatre. Attention was aroused in 1879 when the Comédie-Française took a residency at the Gaiety Theatre, described in The Times as representing "the highest aristocracy of the theatre". The principal demands now coalesced around: a structure in the capital that would form a permanent memorial to Shakespeare; an "exemplary theatre" company producing at the highest level of quality; and a centre from which appreciation of great drama could be spread as part of education throughout the country.[12]

The Shakespeare Memorial Theatre was opened in Stratford upon Avon on 23 April 1879, with the New Shakespeare Company (now the Royal Shakespeare Company, RSC); then Herbert Beerbohm Tree founded an Academy of Dramatic Art at Her Majesty's Theatre in 1904. This still left the capital without a national theatre. A London Shakespeare League was founded in 1902 to develop a Shakespeare National Theatre and – with the impending tercentenary in 1916 of his death – in 1913 purchased land for a theatre in Bloomsbury. This work was interrupted by World War I.

In 1910, George Bernard Shaw wrote a short comedy, The Dark Lady of the Sonnets, in which Shakespeare himself attempts to persuade Elizabeth I of the necessity of building a National Theatre to stage his plays. The play was part of the long-term campaign to build a National Theatre.

| National Theatre Act 1949 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| Long title | An Act to authorise the Treasury to contribute towards the cost of a national theatre, and for purposes connected therewith. |

| Citation | 12, 13 & 14 Geo. 6. c. 16 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 9 March 1949 |

| Commencement | 9 March 1949 |

| Other legislation | |

| Amended by |

|

Status: Amended | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Text of the National Theatre Act 1949 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk. | |

| National Theatre Act 1969 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| Long title | An Act to raise the limit imposed by section 1 of the National Theatre Act 1949 on the contributions which may be made under that section. |

| Citation | 1969 c. 11 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 27 March 1969 |

| Other legislation | |

| Amends | National Theatre Act 1949 |

| National Theatre Act 1974 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| Long title | An Act to remove the limits imposed by the National Theatre Act 1949 on the contributions which may be made under that Act towards the cost of erecting and equipping a national theatre. |

| Citation | 1974 c. 55 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 29 November 1974 |

| Other legislation | |

| Amends | National Theatre Act 1949 |

| Repealed by | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 2013 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

Finally, in 1948, the London County Council (LCC) presented a site close to the Royal Festival Hall for the purpose, so the National Theatre Act 1949 (12, 13 & 14 Geo. 6. c. 16), offering financial support, was passed by Parliament.[13] Ten years after the foundation stone had been laid in 1951, the government declared that the nation could not afford a National Theatre; in response, the LCC offered to waive any rent and pay half the construction costs. The government still tried to apply unacceptable conditions to save money, attempting to force the amalgamation of the existing publicly supported companies: the RSC, Sadler's Wells and Old Vic.[13]

Following some initial inspirational steps taken with the opening of the Chichester Festival Theatre in Chichester in June 1962, the developments in London proceeded. In July 1962, with agreements finally reached, a board was set up to supervise construction, and a separate board was constituted to run a National Theatre Company, which would lease the Old Vic theatre in the interim. The "National Theatre Company" opened on 22 October 1963 with Hamlet, starring Peter O'Toole in the title role.[14] The company was founded by Laurence Olivier, who became the first artistic director of the company. As fellow directors, he enlisted William Gaskill and John Dexter. Among the first ensemble of actors of the company were Robert Stephens, Maggie Smith, Joan Plowright, Michael Gambon, Derek Jacobi, Lynn Redgrave, Michael Redgrave, Colin Blakely and Frank Finlay.

Meanwhile, construction of the permanent theatre proceeded with a design by architects Sir Denys Lasdun and Peter Softley and structural engineers Flint & Neill containing three stages, which opened individually between 1976 and 1977.[15] The construction work was carried out by Sir Robert McAlpine.[16]

The Company remained at the Old Vic until 1976, when construction of the Olivier was complete.[13]

Theatre building and architecture

editTheatres

editThe National Theatre building houses three separate theatres. Additionally, a temporary structure was added in April 2013 and closed in May 2016.

Olivier Theatre

editNamed after the theatre's first artistic director, Laurence Olivier, this is the main auditorium. Modelled on the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus, it has an open stage and a fan-shaped audience seating area for 1160 people. A "drum revolve" (a five-storey revolving stage section) extends eight metres beneath the stage and is operated by a single staff member. The drum has two rim revolves and two platforms, each of which can carry ten tonnes, facilitating dramatic and fluid scenery changes. Its design ensures that the audience's view is not blocked from any seat, and that the audience is fully visible to actors from the stage's centre. Designed in the 1970s and a prototype of current technology, the drum revolve and a multiple "sky hook" flying system were initially very controversial and required ten years to commission, but seem to have fulfilled the objective of functionality with high productivity.[17]

Lyttelton Theatre

editNamed after Oliver Lyttelton, the National Theatre's first board chairman, it has a proscenium arch design and can accommodate an audience of 890.

Dorfman Theatre

editNamed after Lloyd Dorfman (philanthropist and chairman of Travelex Group),[18] the Dorfman is "the smallest, the barest and the most potentially flexible of the National Theatre houses . . . a dark-walled room" with an audience capacity of 400.[19] It was formerly known as the Cottesloe Theatre (named after Lord Cottesloe, Chairman of the South Bank Theatre Board), a name which ceased to be used with the theatre's closure under the National's NT Future redevelopment.

The enhanced[19] theatre reopened in September 2014 under its new name.[20]

Temporary Theatre

editThe Temporary Theatre, formerly called The Shed, was a 225-seat black box theatre which opened in April 2013 and featured new works; it closed in May 2016, following the refurbishment of the Dorfman Theatre.[21]

In 2015 British artist Carl Randall painted a portrait of actress Katie Leung standing in front of The Shed as part of the artist's "London Portraits" series, where he asked various cultural figures to choose a place in London for the backdrop of their portraits.[22][23] Leung explained she chose The Shed as her backdrop because she performed there in the 2013 play The World of Extreme Happiness, and also because "... it's a temporary theatre, it's not permanent, and I wanted to make it permanent in the portrait".[24][25]

Architecture

editThe style of the National Theatre building was described by architecture historian Mark Girouard as "an aesthetic of broken forms" at the time of opening. Architectural opinion was split at the time of construction. Even enthusiastic advocates of the Modern Movement such as Nikolaus Pevsner found the Béton brut RAAC concrete both inside and out overbearing. Most notoriously, the future Charles III described the building in 1988 as "a clever way of building a nuclear power station in the middle of London without anyone objecting". John Betjeman, a man not noted for his enthusiasm for brutalist architecture, wrote to Lasdun stating ironically that he "gasped with delight at the cube of your theatre in the pale blue sky and a glimpse of St Paul's to the south of it. It is a lovely work and so good from so many angles...it has that inevitable and finished look that great work does."[26][27]

Despite the controversy, the theatre has been a Grade II* listed building since 1994.[28] Although the theatre is often cited as an archetype of Brutalist architecture in England, since Lasdun's death the building has been re-evaluated as having closer links to the work of Le Corbusier, rather than contemporary monumental 1960s buildings such as those of Paul Rudolph.[29] The carefully refined balance between horizontal and vertical elements in Lasdun's building has been contrasted favourably with the lumpiness of neighbouring buildings such as the Hayward Gallery and Queen Elizabeth Hall. It is now in the unusual situation of having appeared simultaneously in the top ten "most popular" and "most hated" London buildings in opinion surveys. A recent lighting scheme illuminating the exterior of the building, in particular the fly towers, has proved very popular, and is one of several positive artistic responses to the building. A key intended viewing axis[30] is from Waterloo Bridge at 45 degrees head on to the fly tower of the Olivier Theatre (the largest and highest element of the building) and the steps from ground level. This view is largely obscured now by mature trees along the riverside walk but it can be seen in a more limited way at ground level.

Foyers and interior spaces

editThe National Theatre's foyers are open to the public, with a large theatrical bookshop, restaurants, bars and exhibition spaces. The terraces and foyers of the theatre complex have also been used for ad hoc, short seasonal and experimental performances and screenings. The riverside forecourt of the theatre is used for regular season of open-air performances in the summer months.

The Clore Learning Centre is a new dedicated space for learning at the National Theatre. It offers events and courses for all ages, exploring theatre-making from playwriting to technical skills, often led by the NT's own artists and staff. One of its spaces is The Cottesloe Room, so called in recognition of the original name of the adjacent theatre.

The dressing rooms for all actors are arranged around an internal light-well and air-shaft and so their windows each face each other. This arrangement has led to a tradition whereby, on the opening night (known as "Press Night") and closing night of any individual play, when called to go to "beginners" (opening positions), the actors will go to the window and drum on the glass with the palms of their hands.[31]

Backstage tours run throughout the day and the Sherling High Level Walkway, open daily until 7.30 pm, offers visitors views into the backstage production workshops for set construction and assembly, scenic painting and prop-making.

NT Future

edit2013 saw the commencement of the "NT Future" project; a redevelopment of the National Theatre complex which it was estimated would cost about £80 million.[32]

National Theatre Studio

editThe Studio building across the road from the Old Vic on The Cut in Waterloo. The Studio used to house the NT's workshops, but became the National's research and development wing in 1984. The Studio building houses the New Work Department, the Archive, and the NT's Immersive Storytelling Studio.

The Studio is a Grade II listed building designed by architects Lyons Israel Ellis.[33] Completed in 1958, the building was refurbished by architects Haworth Tompkins and reopened in autumn 2007.

The National Theatre Studio was founded in 1985 under the directorship of Peter Gill, who ran it until 1990.[34] Laura Collier became Head of the Studio in November 2011, replacing Purni Morrell who headed the Studio from 2006.[35] Following the merge of the Studio and the Literary Department under the leadership of Rufus Norris, Emily McLaughlin became the Head of New Work in 2015.

National Theatre Live

editNational Theatre Live is an initiative which broadcasts performances of their productions (and from other theatres) to cinemas and arts centres around the world. It began in June 2009 with Helen Mirren in Jean Racine's Phedre, directed by Nicholas Hytner, in the Lyttelton Theatre.

The third season of broadcasts launched on 15 September 2011 with One Man, Two Guvnors with James Corden. This was followed by Arnold Wesker's The Kitchen. The final broadcast of 2011 was John Hodge's Collaborators with Simon Russell Beale. In 2012 Nicholas Wright's play Travelling Light was broadcast on 9 February, followed by The Comedy of Errors with Lenny Henry on 1 March and She Stoops to Conquer with Katherine Kelly, Steve Pemberton and Sophie Thompson on 29 March.

One Man, Two Guvnors returned to cinema screens in the United States, Canada and Australia for a limited season in Spring 2012. Danny Boyle's Frankenstein also returned to cinema screens worldwide for a limited season in June and July 2012.

The fourth season of broadcasts commenced on Thursday 6 September 2012 with The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, a play based on the international best-selling novel by Mark Haddon. This was followed by The Last of the Haussmans, a new play by Stephen Beresford starring Julie Walters, Rory Kinnear and Helen McCrory on 11 October 2012. William Shakespeare's Timon of Athens followed on 1 November 2012 starring Simon Russell Beale as Timon. On 17 January 2013, NT Live broadcast Arthur Wing Pinero's The Magistrate, with John Lithgow.[36]

The performances to be filmed and broadcast are nominated in advance, allowing planned movement of cameras with greater freedom in the auditorium.

Learning and participation

editNational Theatre Connections

editNational Theatre Connections is the annual nationwide youth theatre festival run by the National Theatre. The festival was founded in 1995, and features ten new plays for young people written by leading playwrights. Productions are staged by schools and youth groups at their schools and community centres, and at local professional theatre hubs. One of the productions of each play is invited to perform in a final festival at the National Theatre, usually in the Olivier Theatre and Dorfman Theatre.

National Theatre Collection

editThe National Theatre Collection (formerly called On Demand. In Schools) is the National Theatre's free production streaming service for educational establishments worldwide, which is free to UK state schools. The service is designed for use by teachers and educators in the classroom, and features recordings of curriculum-linked productions filmed in high definition in front of a live audience.[37]

The service was launched initially to UK secondary schools in 2015 with productions for Key Stage 3 pupils and above. In November 2016, the National Theatre launched to service to UK primary schools, adding a number of new titles for Key Stage 2.[38] Productions currently offered by the service include Frankenstein (directed by Danny Boyle, starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller), Othello (directed by Nicholas Hytner, starting Adrian Lester and Rory Kinnear), Antigone (directed by Polly Findlay, starring Christopher Eccleston and Jodie Whittaker), and Jane Eyre (directed by Sally Cookson).

In 2018, the National Theatre reported that over half of UK state secondary schools have registered to use the service. On Demand. In Schools won the 2018 Bett Award for Free Digital Content or Open Educational Resources.[39]

In March 2020, in light of the coronavirus pandemic, the National Theatre Collection was made available for pupils and teachers to access at home to aid blended learning programmes.[40] In April 2020, six new titles were added to the service to bring the total up to 30 productions. These include Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (directed by Benedict Andrews for the Young Vic, starring Sienna Miller and Jack O'Connell) and Small Island (directed by Rufus Norris for the National Theatre).[41]

Public Acts

editPublic Acts is a community participation programme from the National Theatre working with theatres and community organisations across the UK to create large-scale new work. The first Public Acts production was Pericles in August 2018, at the National Theatre, in the Olivier Theatre. The Guardian described this as 'a richly sung version with brilliant performances from a cast of hundreds.'[42] The second production was As You Like It performed in August 2019 at the Queen's Theatre, Hornchurch.[43][44]

Since 2019, Public Acts has been working on a third production in Doncaster in partnership with Cast and six local community partners.[45] The new adaptation of The Caucasian Chalk Circle was originally planned for 2020 but has been postponed, due to COVID-19.[46]

In December 2020, in partnership with The Guardian, Public Acts released an online musical called We Begin Again by James Graham (Quiz) as a music video and a standalone track released by Broadway Records.[47][48]

Outdoor festivals

editRiver Stage

editRiver Stage is the National Theatre's free outdoor summer festival that place over five weekends outside the National Theatre in its north-east cornersquare. It is accompanied by a number of additional street food stalls and bars run by the NT.

The event features programmes developed by various companies for the first four weekends, with the National Theatre itself programming the fifth weekend. Participating organisations have included The Glory, HOME Manchester, Sadler's Wells, nonclassical, WOMAD, Latitude Festival, Bristol's Mayfest and Rambert. The festival launched in 2015 and is produced by Fran Miller.

Watch This Space

editThe annual "Watch This Space" festival was a free summer-long celebration of outdoor theatre, circus and dance, which was replaced in 2015 by the River Stage festival.

"Watch This Space" featured events for all ages, including workshops and classes for children and adults. "Watch This Space" had a strong national and international relationships with leading and emerging companies working in many different aspects of the outdoor arts sector. Significant collaborators and regular visitors included Teatr Biuro Podrozy, The Whalley Range All Stars, Home Live Art, Addictive TV, Men in Coats, Upswing, Circus Space, Les Grooms, StopGAP Dance Theatre, metro-boulot-dodo, Avanti Display, The Gandinis, Abigail Collins, The World-famous, Ida Barr (Christopher Green), Motionhouse, Mat Ricardo, The Insect Circus, Bängditos Theater, Mimbre, Company FZ, WildWorks, Bash Street Theatre, Markeline, The Chipolatas, The Caravan Gallery, Sienta la Cabeza, Theatre Tuig, Producciones Imperdibles and Mario Queen of the Circus.[49]

The festival was set up by its first producer Jonathan Holloway, who was succeeded in 2005 by Angus MacKechnie.

Whilst the Theatre Square space was occupied by the Temporary Theatre during the NT Future redevelopment, the "Watch This Space" festival was suspended.[50] but held a small number of events in nearby local spaces. In 2013 the National announced that there would be a small summer festival entitled "August Outdoors" in Theatre Square. Playing Fridays and Saturdays only, the programme included The Sneakers and The Streetlights by Half Human Theatre, The Thinker by Stuff & Things, H2H by Joli Vyann, Screeving by Urban Canvas, Pigeon Poo People by The Natural Theatre Company, Capses by Laitrum, Bang On!, Caravania! by The Bone Ensemble, The Hot Potato Syncopators, Total Eclipse of the Head by Ella Good and Nicki Kent, The Caravan Gallery, Curious Curios by Kazzum Theatre and The Preeners by Canopy.[51]

Artistic directors

edit- Sir Laurence Olivier (1963–1973)

- Sir Peter Hall (1973–1988)

- Sir Richard Eyre (1988–1997)

- Sir Trevor Nunn (1997–2003)

- Sir Nicholas Hytner (2003–2015)

- Rufus Norris (2015–2025)

Laurence Olivier became artistic director of the National Theatre at its formation in 1963. He was considered the foremost British film and stage actor of the period, and became the first director of the Chichester Festival Theatre – there forming the company that would unite with the Old Vic Company to form the National Theatre Company. In addition to directing, he continued to appear in many successful productions, not least as Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. In 1969 the National Theatre Company received a Special Tony Award which was accepted by Olivier at the 23rd Tony Awards. He became a life peer in 1970, for his services to theatre, and stepped down in 1973.

Peter Hall took over to manage the move to the South Bank. His career included running the Arts Theatre between 1956 and 1959 – where he directed the English language première of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot. He went on to take over the Memorial Theatre at Stratford, and to create the permanent Royal Shakespeare Company, in 1960, also establishing a new RSC base at the Aldwych Theatre for transfers to the West End. He was artistic director at the National Theatre between 1973 and 1988. During this time he directed major productions for the Theatre, and also some opera at Glyndebourne and the Royal Opera House. After leaving, he ran his own company at The Old Vic and summer seasons at the Theatre Royal, Bath also returning to guest direct Tantalus for the RSC in 2000 and Bacchai in the National Theatre's Olivier and Twelfth Night in the Dorfman some years later. In 2008, he opened a new theatre, The Rose, and remained its Director Emeritus until his death in 2017.

One of the National's associate directors under Peter Hall, Richard Eyre, became artistic director in 1988; his experience included running the Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh and the Nottingham Playhouse. He was noted for his series of collaborations with David Hare on the state of contemporary Britain.

In 1997, Trevor Nunn became artistic director. He came to the National from the RSC, having undertaken a major expansion of the company into the Swan, The Other Place and the Barbican Theatres. He brought a more populist style to the National, directing My Fair Lady, Oklahoma! and South Pacific.

In April 2003, Nicholas Hytner took over as artistic director. He previously worked as an associate director with the Royal Exchange Theatre and the National. A number of his successful productions have been made into films. In April 2013 Hytner announced he would step down as artistic director at the end of March 2015.[52][53]

Amongst Hytner's innovations were NT Future, the National Theatre Live initiative of simulcasting live productions, and the Entry Pass scheme, allowing young people under the age of 26 to purchase tickets for £7.50 to any production at the theatre.

Rufus Norris took over as artistic director in March 2015. He is the first person since Laurence Olivier to hold the post without being a University of Cambridge graduate. In June 2023 it was announced that Norris would be stepping down in 2025.[54]

It was announced in December 2023 that Indhu Rubasingham would take over as artistic director in 2025.[55]

Notable productions

edit1963–1973

edit- In 1962, the company of The Old Vic theatre was dissolved, and reconstituted as the "National Theatre Company" opening on 22 October 1963 with Hamlet. The company remained based in The Old Vic until the new buildings opened in February 1976. The National Theatre Board was established in February 1963, formally gaining the Royal prefix in 1990.

- Hamlet, directed by Laurence Olivier, with Peter O'Toole in the title role and Michael Redgrave as Claudius (1963)

- The Recruiting Officer, directed by William Gaskill with Laurence Olivier as Captain Brazen, Maggie Smith as Sylvia and Robert Stephens as Captain Plume (1963).

- Othello, directed by John Dexter, with Laurence Olivier in the title role, Frank Finlay as Iago and Maggie Smith as Desdemona (1964)

- The Royal Hunt of the Sun by Peter Shaffer, directed by John Dexter (1964); the National's first world premiere

- Hay Fever, directed by Noël Coward starring Edith Evans as Judith, Maggie Smith as Myra, Derek Jacobi as Simon, Barbara Hicks as Clara, Anthony Nicholls as David, Robert Stephens as Sandy, Robert Lang as Richard, and Lynn Redgrave as Jackie (1964).

- Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Franco Zeffirelli with Maggie Smith, Robert Stephens, Ian McKellen, Lynn Redgrave, Albert Finney, Michael York and Derek Jacobi among others (1965).

- Miss Julie by August Strindberg, directed by Michael Elliott with Albert Finney and Maggie Smith in a double bill with Black Comedy by Peter Shaffer, directed by John Dexter with Derek Jacobi and Maggie Smith. (1965/66)

- As You Like It directed by Clifford Williams, the all-male production with Ronald Pickup as Rosalind, Jeremy Brett as Orlando, Charles Kay as Celia, Derek Jacobi as Touchstone, Robert Stephens as Jaques (1967)

- Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by Tom Stoppard, directed by Derek Goldby, with John Stride and Edward Petherbridge (1967)

- The Dance of Death by August Strindberg, with Laurence Olivier as Edgar, Geraldine McEwan as Alice and Robert Stephens as Kurt (1967)

- Oedipus by Seneca translated by Ted Hughes, directed by Peter Brook, with John Gielgud as Oedipus, Irene Worth as Jocasta (1968)

- The Merchant of Venice, directed by Jonathan Miller, with Laurence Olivier as Shylock and Joan Plowright as Portia (1970)

- Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen, directed by Ingmar Bergman, with Maggie Smith as Hedda (1970)

- Long Day's Journey into Night by Eugene O'Neill, directed by Michael Blakemore, with Laurence Olivier as James Tyrone (1971)

- Jumpers by Tom Stoppard, directed by Peter Wood, starring Michael Hordern and Diana Rigg (1972)

- The Misanthrope by Molière, translated by Tony Harrison, directed by John Dexter with Alec McCowen and Diana Rigg (1973–74)

1974–1987

edit- The Tempest with John Gielgud as Prospero, directed by Peter Hall (1974)

- Eden End by J.B. Priestley, with Joan Plowright as Stella and Michael Jayston as Charles (1974)

- No Man's Land by Harold Pinter, directed by Peter Hall, with Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud (1975)

- Illuminatus!, an eight-hour five-play cycle from Ken Campbell's The Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool (1977)

- Bedroom Farce by Alan Ayckbourn, directed by Peter Hall (1977)

- Lark Rise by Keith Dewhurst, directed by Bill Bryden (1978)

- Tales from the Vienna Woods by Ödön von Horváth, translated by Christopher Hampton, directed by Maximilian Schell, with Stephen Rea and Kate Nelligan

- Plenty by David Hare, directed by the author, with Stephen Moore and Kate Nelligan (1978)

- Amadeus by Peter Shaffer, directed by Peter Hall, with Paul Scofield and Simon Callow (1979–80)

- Galileo, by Bertolt Brecht, translated by Howard Brenton directed by John Dexter with Michael Gambon (1980)

- The Romans in Britain by Howard Brenton, directed by Michael Bogdanov, subject of an unsuccessful private prosecution by Mary Whitehouse (1980)

- The Oresteia by Aeschylus, translated by Tony Harrison, directed by Peter Hall (1981)

- A Kind of Alaska, one-act play by Harold Pinter, directed by Peter Brook, with Judi Dench. Inspired by Awakenings, by Oliver Sacks. (1982)

- Guys and Dolls, the National's first musical, directed by Richard Eyre, starring Bob Hoskins, Julia McKenzie, Ian Charleson, and Julie Covington (1982)

- Glengarry Glen Ross by David Mamet, directed by Bill Bryden (1983)

- Jean Seberg, musical with a book by Julian Barry, lyrics by Christopher Adler, and music by Marvin Hamlisch; directed by Peter Hall (1983)

- Fool for Love by Sam Shepard, starring Ian Charleson and Julie Walters, directed by Peter Gill (1984)

- The Mysteries from medieval Mystery plays in a version by Tony Harrison, directed by Bill Bryden (1985)

- Pravda by Howard Brenton and David Hare, directed by David Hare, with Anthony Hopkins (1985)

- The American Clock by Arthur Miller, directed by Peter Wood (1986)

- Antony and Cleopatra directed by Peter Hall, with Anthony Hopkins and Judi Dench (1987)

- Happy Birthday, Sir Larry directed by Mike Ockrent and Jonathan Myerson, with a cast including Peggy Ashcroft, Peter Hall, Antony Sher, Albert Finney (31 May 1987) an 80th Birthday Tribute to Sir Laurence Olivier[56]

1988–1997

edit- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, directed by Howard Davies, starring Ian Charleson and Lindsay Duncan (1988)

- Fuente Ovejuna by Lope de Vega, translated by Adrian Mitchell, directed by Declan Donnellan (1989)

- Hamlet, starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Judi Dench, later Ian Charleson, directed by Richard Eyre (1989)

- The Voysey Inheritance, starring Jeremy Northam, directed by Richard Eyre

- Richard III starring Ian McKellen and directed by Richard Eyre (1990)

- Sunday in the Park with George by Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine, directed by Steven Pimlott (British premiere) (1990)

- The Madness of George III by Alan Bennett, directed by Nicholas Hytner, starring Nigel Hawthorne (1991)

- Angels in America by Tony Kushner, directed by Declan Donnellan (1991–92)

- Carousel by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, directed by Nicholas Hytner (1993)

- An Inspector Calls by J. B. Priestley, directed by Stephen Daldry (1992)

- Racing Demon, Murmuring Judges, and The Absence of War, by David Hare, directed by Richard Eyre (1993)

- Arcadia by Tom Stoppard, directed by Trevor Nunn (1993)

- Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street by Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler, directed by Declan Donnellan (1993)

- Hedda Gabler starring Fiona Shaw, directed by Deborah Warner (1993)

- Les Parents Terribles by Jean Cocteau, directed by Sean Mathias (1994)

- Women of Troy by Euripides, directed by Annie Castledine, starring Josette Bushell-Mingo, Rosemary Harris and Jane Birkin (1995)

- A Little Night Music by Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler, directed by Sean Mathias, with Judi Dench (1995)

- Anna Karenina adapted by Helen Edmundson, with Anne-Marie Duff (1996)[57]

- King Lear directed by Richard Eyre, with Ian Holm (1997)

- The Caucasian Chalk Circle by Bertolt Brecht, translated by Frank McGuinness, directed by Simon McBurney (1997)

1998–2002

edit- Copenhagen by Michael Frayn, directed by Michael Blakemore (1998)

- Oklahoma! by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, directed by Trevor Nunn, with Maureen Lipman and Hugh Jackman (1998)

- Our Lady of Sligo by Sebastian Barry, directed by Max Stafford-Clark, with Sinéad Cusack (1998)

- Candide by Leonard Bernstein, directed by John Caird assisted by Trevor Nunn (1999)

- The Merchant of Venice directed by Trevor Nunn, with Henry Goodman (1999)

- Summerfolk by Maxim Gorky, directed by Trevor Nunn (1999)

- Honk!, Laurence Olivier Award winner (1999)

- Money by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, directed by John Caird (1999)

- Albert Speer by David Edgar, with Alex Jennings (2000)

- Blue/Orange by Joe Penhall directed by Roger Michell, with Chiwetel Ejiofor, Bill Nighy and Andrew Lincoln (2000)

- The Island by Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona, directed by Peter Brook and performed by Kani and Ntshona (2000)

- Far Side of the Moon written, directed and performed by Robert Lepage (2001)

- Humble Boy by Charlotte Jones directed by John Caird, with Simon Russell Beale (2001)

- South Pacific by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, directed by Trevor Nunn, with Philip Quast who won the 2002 Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical and Lauren Kennedy (2001)

- The Winter's Tale by William Shakespeare directed by Nicholas Hytner, with Alex Jennings and Phil Daniels (2001)

- Vincent in Brixton by Nicholas Wright, directed by Richard Eyre, with Clare Higgins (2002)

- The Coast of Utopia, a trilogy by Tom Stoppard, comprising: Voyage, Shipwreck and Salvage, directed by Trevor Nunn, with computerised video designs by William Dudley (2002)

- Anything Goes by Cole Porter, directed by Trevor Nunn, with John Barrowman and Sally Ann Triplett (2002)

- Dinner by Moira Buffini, with Harriet Walter, Nicholas Farrell and Catherine McCormack, directed by Fiona Buffini (2002)

- A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams, with Glenn Close, Iain Glen and Essie Davis, directed by Trevor Nunn (2002)

2003–2014

edit- Henry V by William Shakespeare, directed by Nicholas Hytner starring Adrian Lester (2003)

- Jerry Springer: The Opera, a musical by Stewart Lee and Richard Thomas (2003)

- His Dark Materials, a two-part adaptation of Philip Pullman's novel directed by Nicholas Hytner starring Anna Maxwell Martin, Dominic Cooper, Patricia Hodge and Niamh Cusack (2003)

- The History Boys by Alan Bennett, directed by Nicholas Hytner, starring Richard Griffiths, Frances de la Tour and Dominic Cooper (2004)

- Coram Boy by Helen Edmundson, with Bertie Carvel and Paul Ritter (2005–2006)[58]

- Laurence Olivier Celebratory Performance directed by Nicholas Hytner and Angus MacKechnie. A one-off tribute to Lord Laurence Olivier, the National's first director, in his centenary year and starring Richard Attenborough, Claire Bloom, Rory Kinnear, and Alex Jennings (23 September 2007)

- War Horse based on a novel by Michael Morpurgo, adapted by Nick Stafford, directed by Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris, presented in association with Handspring (2007–2009)

- Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Nicholas Hytner, with Simon Russell Beale and Zoë Wanamaker (2007–2008)

- Never So Good by Howard Brenton, directed by Howard Davies with Jeremy Irons (2008)

- Mother Courage and Her Children, by Bertolt Brecht, with Fiona Shaw (2009)

- Phèdre featuring Helen Mirren, Margaret Tyzack and Dominic Cooper, directed by Nicholas Hytner (2009)

- The Habit of Art, by Alan Bennett, with Richard Griffiths, directed by Nicholas Hytner(2010)

- Frankenstein, directed by Danny Boyle and starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller (2011)

- One Man, Two Guvnors, based on Servant of Two Masters by Richard Bean, with James Corden, directed by Nicholas Hytner (2011)[59]

- London Road, a musical by Alecky Blythe and Adam Cork, directed by Rufus Norris (2011)

- The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Simon Stephens, adapted from the novel of the same name by Mark Haddon, with Luke Treadaway, Nicola Walker, Niamh Cusack and Paul Ritter (2012).[60]

- Othello by William Shakespeare with Adrian Lester and Rory Kinnear, directed by Nicholas Hytner (2013)

- National Theatre: 50 Years on Stage. Celebrating the 50th anniversary, a selection of scenes from various productions in the National Theatre's history, featuring Angels in America, One Man, Two Guvnors, London Road, Jerry Springer: The Opera and Guys and Dolls, featuring Maggie Smith, Derek Jacobi, Adrian Lester, Joan Plowright, Judi Dench, Rory Kinnear, Helen Mirren and Alex Jennings. Directed by Nicholas Hytner and designed by Mark Thompson(2013)

- King Lear by William Shakespeare, with Simon Russell Beale, directed by Sam Mendes (2014)[61]

2015–present

edit- Everyman adapted by Carol Ann Duffy, starring Chiwetel Ejiofor, directed by Rufus Norris (2015)

- People, Places & Things by Duncan MacMillan, directed by Jeremy Herrin, starring Denise Gough (2015)

- Cleansed by Sarah Kane, directed by Katie Mitchell (2016)

- The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan, directed by Carrie Cracknell starring Helen McCrory (2016)

- Amadeus by Peter Shaffer, directed by Michael Longhurst, starring Lucian Msamati and Adam Gillen (2016 and 2018)

- Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen, directed by Ivo van Hove, starring Ruth Wilson, a re-working of the production previously staged at the Toneelgrope Amsterdam and New York Theatre Workshop (2016)

- Les Blancs by Lorraine Hansberry, final text adapted by Robert Nemiroff, directed by Yaël Farber, starring Danny Sapani and Siân Phillips (2016)[62]

- Angels in America by Tony Kushner, directed by Marianne Elliott, starring Andrew Garfield, Denise Gough, James McArdle, Russell Tovey and Nathan Lane (2017)

- Follies, music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and book by James Goldman, directed by Dominic Cooke, starring Imelda Staunton, Janie Dee, Philip Quast and Tracie Bennett (2017; return engagement in 2019)

- Beginning by David Eldridge, directed by Polly Findlay (2017)

- Network, directed by Ivo van Hove, based on the Sidney Lumet film, adapted by Lee Hall, starring Bryan Cranston (2017)

- John by Annie Baker, directed by James Macdonald (2018)

- Nine Night by Natasha Gordon, directed by Roy Alexander Weise, starring Cecilia Noble (2018)

- Translations by Brian Friel, directed by Ian Rickson, starring Colin Morgan and Ciarán Hinds (2018)

- Julie by Polly Stenham, directed by Carrie Cracknell, starring Vanessa Kirby and Eric Kofi Abrefa (2018)

- An Octoroon by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, directed by Ned Bennett, a co-production with Orange Tree Theatre (2018)

- The Lehman Trilogy by Stefano Massini, adapted by Ben Power, directed by Sam Mendes, starring Adam Godley, Ben Miles, and Simon Russell Beale, a co-production with Neal Street Productions (2018)

- Pericles by William Shakespeare, adapted by Chris Bush, directed by Emily Lim, the first Public Acts production (2018)

- Antony and Cleopatra by William Shakespeare, directed by Simon Godwin, starring Ralph Fiennes and Sophie Okonedo (2018)

- Hadestown, music, lyrics, and book by Anaïs Mitchell, directed by Rachel Chavkin (2018)[63]

- When We Have Sufficiently Tortured Each Other: Twelve Variations on Samuel Richardson's Pamela by Martin Crimp, directed by Katie Mitchell, starring Cate Blanchett and Stephen Dillane (2019)

- The Ocean at the End of the Lane based on a novel by Neil Gaiman (2019)

- The Crucible by Arthur Miller, directed by Lyndsey Turner and designed by Es Devlin (2022)

- Standing at the Sky's Edge book by Chris Bush with songs by Richard Hawley (2023)

- Dear England by James Graham directed by Rupert Gould (2023)

- The Witches (2023–2024)

- The House of Bernarda Alba (2023–2024)

- Dear Octopus (2024) directed by Emily Burns [64]

Royal patrons

edit- Queen Elizabeth II 1974 – 2019

- Meghan, Duchess of Sussex January 2019 – February 2021[65][66]

- Queen Camilla March 2022 – present[67]

Gallery

edit-

An artistic lighting scheme illuminating the exterior of the building

-

The statue of Laurence Olivier as Hamlet was unveiled in September 2007

-

The terrace entrance between the mezzanine restaurant level and the Olivier cloakroom level, reached from halfway up/down Waterloo Bridge

-

The main entrance on the ground floor

-

The ensemble shows a varying range of geometric relationships.

-

River Thames and Waterloo Bridge, with National Theatre, centre-right

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Hartnoll, Phyllis; Found, Peter (1 January 2003), Hartnoll, Phyllis; Found, Peter (eds.), "National Theatre", The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780192825742.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-282574-2, retrieved 20 December 2023

- ^ Lister, David (11 January 2003). "Wales and Scotland need a cultural revolution". The Independent. London.

- ^ "Home page". The National Theatre. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

Welcome to the National Theatre

- ^ "National Theatre Near You". Royal National Theatre. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Slawson, Nicola (17 February 2021). "National Theatre to halt Europe tours over Brexit rules". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ The Cambridge History of British Theatre, Volume 3, p. 319

- ^ Marshall, Alex (December 2020). "U.K. National Theater Enters the Streaming Wars". New York Times. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "National Theatre at Home". National Theatre. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ National Theatre Annual Report 2012-13

- ^ Dramaticus The stage as it is (1847)

- ^ Effingham William Wilson A House for Shakespeare. A proposition for the consideration of the Nation and a Second and Concluding Paper (1848)

- ^ Woodfield, James (1984). English Theatre in Transition, 1881–1914: 1881–1914. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 95–107. ISBN 0-389-20483-8.

- ^ a b c Findlater, Richard The Winding Road to King's Reach (1977), also in Callow. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ "Monitor - Prince of Denmark". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Denys Lasdun and Peter Hall talk about the building". History of the NT. Royal National Theatre. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ "A portrait of achievement" (PDF). Sir Robert McAlpine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ History of the Drum Revolve Archived 30 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine at National Theatre website

- ^ Brown, Mark (28 October 2010). "National Theatre's Cottesloe venue to be renamed after £10m donor". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Dorfman Theatre". Royal National Theatre. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Quinn, Michael (2 July 2014). "National's Dorfman Theatre to open with Fatboy Slim musical". The Stage. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "National Theatre reveals closing date for Temporary Theatre". The Stage. 19 April 2016.

- ^ Carl Randall's "London Portraits" on display in National Portrait Gallery., The Royal Drawing School, London, 2016, retrieved 20 March 2021

- ^ Actress Katie Leung and The Shed., Carl Randall's artist website, 2016, archived from the original on 20 March 2021, retrieved 20 March 2021

- ^ Carl Randall's London Portraits – Video Documentary., The Daiwa Anglo Japanese Foundation London, 2016, archived from the original on 10 August 2016, retrieved 20 March 2021

- ^ London Portraits – Video Documentary., Youtube, 2016, archived from the original on 20 March 2021, retrieved 20 March 2021

- ^ Pearman, Hugh (21 January 2001). "Gabion: The legacy of Lasdun 2/2". Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- ^ Richard J. Williams. "What is: Brutalism?". HENI Talks.

- ^ Historic England (23 June 1994). "Royal National Theatre (1272324)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ Rykwert, Joseph (12 January 2001). "Sir Denys Lasdun obituary". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ Denys Lasdun: Architecture, City, Landscape by William J R Curtis Phaidon Press 1994

- ^ Lithgow, John (13 January 2013). "A Lone Yank Takes Joy in Togetherness". The New York Times. p. AR7. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "Welcome to National Theatre NT Future" Archived 6 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Royal National Theatre. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Historic England. "Royal National Theatre Studio (1391540)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ Cavendish, Dominic (28 November 2007). "National Theatre Studio: More power to theatre's engine room – Telegraph". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- ^ "Collier to Head NT Studio" Archived 12 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The British Theatre Guide, 20 October 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ The Magistrate Archived 7 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Royal National Theatre.

- ^ "National Theatre On demand. In Schools". schools.nationaltheatre.org.uk. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Third of secondary schools sign up to National Theatre's streaming service | News | The Stage". The Stage. 4 November 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "2018 winners | Bett Awards". bettawards.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "National Theatre collection available to pupils and teachers at home for free". Voice Online. 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Davies, Alan (26 April 2020). "Teachers and students able to access National Theatre Collection". Welwyn Hatfield Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "Pericles review – musical Shakespeare adaptation is a joy". The Guardian. 30 August 2018. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "Review: As You Like It (Queen's Theatre, Hornchurch) | WhatsOnStage". www.whatsonstage.com. 27 August 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Gillinson, Miriam (27 August 2019). "As You Like It review – musical take on Shakespeare inspires and thrills". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ "National Theatre announces new works and star casts". British Theatre. 13 June 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "Public Acts | National Theatre". www.nationaltheatre.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "James Graham on his uplifting 2020 musical: 'We want to look forward'". The Guardian. 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "National Theatre's Public Acts Community Members Perform in Online Musical "We Begin Again" Produced by The Guardian, in Partnership with National Theatre - Theatre Weekly". 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "Watch This Space Festival" Archived 19 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Royal National Theatre

- ^ "Watch This Space Festival" Archived 12 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Royal National Theatre

- ^ "Watch this Space presents August Outdoors". Royal National Theatre. Archived from the original on 5 August 2013.

- ^ Charlotte Higgins (10 April 2013)."Sir Nicholas Hytner to step down as National Theatre artistic director" Archived 20 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ "Sir Nicholas Hytner to leave National Theatre" Archived 20 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 10 April 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ "Rufus Norris to step down as Director in 2025". www.nationaltheatre.org.uk. 15 June 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ Khomami, Nadia; Bakare, Lanre (13 December 2023). "Indhu Rubasingham chosen as National Theatre's next director". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Theatre programme for Happy Birthday, Sir Larry, dated 31 May 1987

- ^ "Tolstoy's epic novel "War and Peace" has been reduced to just a few hours on stage | the Independent | the Independent". Independent.co.uk. 7 February 2008. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "Coram Boy, National Theatre, London | the Independent". Independent.co.uk. 21 December 2006. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ One Man, Two Guvnors Archived 8 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Onemantwoguvnors.com.

- ^ The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time Archived 23 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Royal National Theatre.

- ^ King Lear Archived 20 May 2014 at archive.today. Royal National Theatre.

- ^ "Les Blancs | National Theatre". www.nationaltheatre.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Paulson, Michael (19 April 2018). "The Underworld Will Stop in London en Route to Broadway". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Swain, Marianka (15 February 2024). "Dear Octopus: Lindsay Duncan is a catty delight in this forgotten West End hit". telegraph.

- ^ "Meghan made patron of National Theatre". BBC News. 10 January 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Harry and Meghan not returning as working members of Royal Family". BBC News. 19 February 2021. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Camilla replaces Meghan as royal patron of National Theatre". Sky News. 18 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

Bibliography

edit- Elsom, John and Tomalin, Nicholas (1978): The History of the National Theatre. Jonathan Cape, London. ISBN 0-224-01340-8.

- Hall, Peter, (edited Goodwin, John) (1983): Peter Hall's Diaries: The Story of a Dramatic Battle (1972–79). Hamish Hamilton, London. ISBN 0-241-11047-5.

- Goodwin, Tim (1988), Britain's Royal National Theatre: The First 25 Years. Nick Hern Books, London. ISBN 1-85459-070-7.

- Callow, Simon (1997): The National: The Theatre and its Work, 1963–1997. Nick Hern Books, London. ISBN 1-85459-318-8.

Further reading

edit- Rosenthal, Daniel (2013). The National Theatre Story. Oberon Books: London. ISBN 978-1-84002-768-6

- Dillon, Patrick [Tilson, Jake – designed by] (2015). Concrete Reality: Building the National Theatre National Theatre: London. ISBN 978-0-95722-592-3

External links

edit- Official website

- NT Live

- NT Connections Archived 6 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- History of the National Theatre with archive images and press reports on the building at The Music Hall and Theatre Site dedicated to Arthur Lloyd

- Shakespeare at the National Theatre, 1967–2012, compiled by Daniel Rosenthal, on Google Arts & Culture

- National Theatre's Black Plays Archive, supported by Sustained Theatre and Arts Council England

- National Theatre Act 1949 on the UK Parliament website