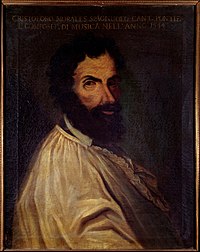

Cristóbal de Morales (c. 1500 – between 4 September and 7 October 1553) was a Spanish composer of the Renaissance. He is generally considered to be the most influential Spanish composer before Tomás Luis de Victoria.[citation needed]

Life

editCristóbal de Morales was born in Seville and, after an exceptional early education there, which included a rigorous training in the classics as well as musical study with some of the foremost composers, he held posts at Ávila and Plasencia. All that is known about his family is that he had a sister, and that his father died prior to his sister's marriage in 1530. Others who lived in Seville are considered to be potential relatives of Morales. These include Cristóbal de Morales, a singer employed by Duke of Medina Sidonia in 1504; Alonso de Morales, treasurer of the cathedral in 1503; Francisco de Morales (d. 1505), a canon; and Diego de Morales, who was the cathedral notary in 1525.

Earlier Spanish popes of the Borja family held a long tradition of employing Spanish singers in the papal chapel’s choir. This had a significant effect on Morales' success. Starting in 1522, there are three different occurrences where a Cristóbal de Morales was indicated to be an organist. There is little information of the whereabouts of Morales from January 1532 to May 1534. Morales is documented three times in Rome as ‘presbyter toletanus’ in May and December 1534. By 1535 he had moved to Rome, where he was a singer in the papal choir, evidently due to the interest of Pope Paul III who was partial to Spanish singers. He remained in Rome until 1545, in the employ of the Vatican; then, after a period of unsuccessfully seeking other employment in Italy (with the emperor, as well as with Cosimo I de Medici) he returned to Spain, where he held a succession of posts, many of which were marred by financial or political difficulties. The last of these was as maestro di capilla at Málaga Cathedral in his native Andalusia from 1551–53. While he was renowned by this time as one of the greatest composers in Europe, he seems to have been unpopular as an employee, for he began to have difficulty finding and keeping positions.

Morales’s fame was due in part to the numerous testimonials of those around him. The Spanish theorist Juan Bermudo declared him “the light of Spain in music”, while in 1559, a Mexican choir – Spanish polyphony in particular was quick to reach the New World – sang his music at a service commemorating the death of Charles V the previous year. This fame continued into the 18th century when Andrea Adami da Bolsena, biographer of many papal musicians, praised him as the papal chapel’s most important composer between Josquin des Prez and Palestrina.

There is recurrent evidence that he was a difficult character, aware of his exceptional talent, and probably came across as arrogant and incapable of getting along with those of lesser musical abilities. He made severe demands on the singers in his employ and alienated employers. In spite of this, he was regarded as one of the finest composers in Europe around the middle of the 16th century.[1]

On 4 September 1553 he asked to be considered for the position of maestro de capilla at the Cathedral of Toledo, where he had previously worked, but shortly afterwards he died in Marchena; the actual date is not known, but was before October 7.[1]

Music and influence

editAlmost all of his music is sacred, and all of it is vocal, though instruments may have been used in an accompanying role in performance. He wrote many masses, some of spectacular difficulty, most likely written for the expert papal choir; he wrote over 100 motets; and he wrote 18 settings of the Magnificat, and at least five settings of the Lamentations of Jeremiah (one of which survives from a single manuscript in Mexico). The Magnificats alone set him apart from other composers of the time, and they are the portion of his work most often performed today. Stylistically, his music has much in common with other middle Renaissance work of the Iberian peninsula, for example a preference for harmony heard as functional by the modern ear (root motions of fourths or fifths being somewhat more common than in, for example, Gombert or Palestrina), and a free use of harmonic cross-relations rather like one hears in English music of the time, for example in Thomas Tallis. Some unique characteristics of his style include the rhythmic freedom, such as his use of occasional three-against-four polyrhythms, and cross-rhythms where a voice sings in a rhythm following the text but ignoring the meter prevailing in other voices. Late in life he wrote in a sober, heavily homophonic style, but all through his life he was a careful craftsman who considered the expression and understandability of the text to be the highest artistic goal.

Morales was the first Spanish composer of international renown. His works were widely distributed in Europe, and many copies made the journey to the New World. Many music writers and theorists in the hundred years after his death considered his music to be among the most perfect of the time.

Masses

editMorales's masses, of which 22 survive, use a variety of techniques, including cantus firmus and parody. Six masses are based on Gregorian chant, and these are mostly written in a conservative cantus-firmus style. Eight of his masses use the parody technique, including one for six voices based on the famous chanson Mille regretz, attributed to Josquin des Prez. The melody is arranged so that it is clearly audible in every movement, usually in the highest voice, giving the work considerable stylistic and motivic unity. Morales also wrote two masses on the famous L'homme armé tune, which was so often set by composers in the late 15th century and 16th century; one of these is for four voices, and the other for five. The four voice mass uses the tune as a strict cantus firmus, and the setting for five voices treats it more freely, migrating it from one voice to another.[2]

In addition, he wrote a Missa pro defunctis (a Requiem mass). Its peculiarities of transmission, as well as its apparent incomplete editing, suggest that it may be his last work.[1]

Works

edit- 22 masses

- Missarum Liber primus (Rome, 1544)

- Missa Aspice Domine 4v

- Missa Ave Maris Stella 4v

- Missa De Beata Virgine 4v

- Missa L'homme armé 5v

- Missa Mille Regretz 6v

- Missa Quaeramus cum pastoribus 5v

- Missa Si bona suscepimus 6v

- Missa Vulnerasti cor meum 4v

- Missarum Liber secundus (Rome, 1544)

- Missa Benedicta est regina caelorum [= Missa Valenciana] 4v

- Missa De Beata Virgine 5v

- Missa Gaude Barbara 4v

- Missa L’homme armée 4v

- Missa Pro defunctis 5v

- Missa Quem dicunt homines 5v

- Missa Tu es vas electionis 4v

- Others:

- Missa Caça

- Missa Cortilla

- Missa Desilde al cavallero 4v

- Missa Super Ut re mi fa sol la 4v

- Missa Tristezas me matan 5v

- Officium defunctorum 4v (ca. 1526–28)

- Missarum Liber primus (Rome, 1544)

- 18 settings of the Magnificat

- 5 Lamentations of Jeremiah

- over 100 motets

Recordings

edit- Cristóbal de Morales, Messe Mille Regretz. Victor Alonso, Concert de les Arts. CD Accord 204662.

- Cristóbal de Morales, Missa de Beata Virgine (a5). Collegium Vocale Gent, Philippe Herreweghe. The V. Sessions, 2009.

- Cristóbal de Morales, Missa de Beata Virgine. Ensemble Jachet de Mantoue. CD Calliope 9363.

- Cristóbal de Morales, Missa mille regretz. Paul McCreesh, Gabrieli Consort & Players. CD Archiv 474 228-2.

- Cristóbal de Morales, Missa Si bona suscepimus. The Tallis Scholars, Peter Phillips. Gimell CDGIM 033.

- Cristóbal de Morales, Missa Vulnerasti cor meum. – Canticum Canticorum. Orchestra of the Renaissance, Richard Cheetham, Michael Noone. Glossa cabinet GCD C81403.

- Cristóbal de Morales, Morales en Toledo. Michael Noone, Ensemble Plus Ultra. GCD 922001

- Cristóbal de Morales, Office des Ténèbres. Denis Raisin-Dadre, Doulce Mémoire. Naïve E 8878

Office of the Dead/Requiem

edit- Cristóbal de Morales, Officium (Parce mihi Domine). Jan Garbarek and the Hilliard Ensemble. ECM 1525

The 'Parce mihi Domine' from his Officium Defunctorum was used as the key track (in three versions) on the best selling Jazz and Classical Album of 1994, Officium, by Jan Garbarek and the Hilliard Ensemble.

- Cristóbal de Morales, Morales: Requiem. Paul McCreesh, Gabrieli Consort. CD Archiv 457 597-2

- Cristóbal de Morales, Officium defunctorum, Missa pro Defunctis. La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Hespèrion XX, Jordi Savall. Naive ES 9926.

Notes

editReferences

edit- Blanche Gangwere, Music History During the Renaissance Period, 1520–1550. Westport, Connecticut, Praeger Publishers. 2004.

- Robert Stevenson/Alejandro Planchart: Cristóbal Morales, Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed November 9, 2006), (subscription access) Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

edit- Article "Cristóbal de Morales," in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. 20 vol. London, Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1980. ISBN 1-56159-174-2

- Stevenson, Robert M. Cristóbal de Morales (ca. 1500-1553): Light of Spain in Music. "Inter-American Music Review" 13/2 (Spring-Summer 1993): 1–105.

- Gustave Reese, Music in the Renaissance. New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 1954. ISBN 0-393-09530-4

- Atlas, Allan W. Renaissance music: music in Western Europe, 1400-1600. New York, N.Y. W.W. Norton and Company, 1998.

- G. Edward Bruner, DMA: Editions and Analysis of Five Missa Beata Virgine Maria by the Spanish Composers: Morales, Guerrero, Victoria, Vivanco, and Esquivel. DMA diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1980. Facsimile: University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

External links

edit- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Free scores by Cristóbal de Morales at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Cristóbal de Morales in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Maestros del Siglo de Oro, Morales, Guerrero, Victoria, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Hespèrion XX, dir. Jordi Savall, Alia Vox AVSA9867

- Morales Mass Book (CC-BY-NC, 2017)