This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2022) |

Emperor Yuan of Han, personal name Liu Shi (劉奭; 75 BC – 8 July 33 BC), was an emperor of the Chinese Han dynasty. He reigned from 48 BC to 33 BC. Emperor Yuan promoted Confucianism as the official creed of the Chinese government. He appointed adherents of Confucius to important government posts.

| Emperor Yuan of Han 漢元帝 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

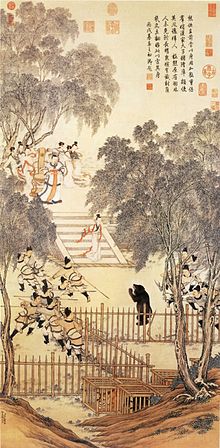

Jieyu Fighting against Bear by Jin Tingbiao, Palace Museum, China. Emperor Yuan was depicted at the top of the flight of steps. | |||||||||

| Emperor of the Han dynasty | |||||||||

| Reign | 29 January 48[1] – 8 July 33 BC | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Emperor Xuan | ||||||||

| Successor | Emperor Cheng | ||||||||

| Born | 75 BC Chang'an, Han Empire | ||||||||

| Died | 8 July 33 BC (aged 42) Chang'an, Han Empire | ||||||||

| Burial | Wei Mausoleum (渭陵), Xianyang | ||||||||

| Consorts | Empress Xiaoyuan Consort Fu Consort Feng Consort Wei | ||||||||

| Issue | Emperor Cheng of Han Liu Kang, Prince Gong of Dingtao Liu Xing, Prince Xiao of Zhongshan Princess Pingdou Princess Pingyang Princess Yingyi | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| House | Liu | ||||||||

| Dynasty | Han (Western Han) | ||||||||

| Father | Emperor Xuan | ||||||||

| Mother | Empress Gong'ai | ||||||||

| Emperor Yuan of Han | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 漢元帝 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉元帝 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | The Primal Emperor of Han | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 劉奭 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 刘奭 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | (personal name) | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

However, at the same time that he was solidifying Confucianism's position as the official ideology, the empire's condition slowly deteriorated due to his indecisiveness, his inability to stop factional infighting between officials in his administration, and the trust he held in certain corrupt officials. He was succeeded by Emperor Cheng.

Family background

editWhen Emperor Yuan was born Liu Shi in 75 BC, his parents Liu Bingyi and Xu Pingjun were commoners without titles. Bingyi was a great-grandson of Emperor Wu, and his grandfather Liu Ju was Emperor Wu's crown prince, until Emperor Wu's paranoia forced him into a failed rebellion in 91 BC while Bingyi was still just an infant. The aftermath of the failed rebellion was that Prince Ju committed suicide and his entire family was executed. Bingyi was spared because of his young age, but became a commoner and survived on the largess of others. One of his supporters was chief eunuch Zhang He, who had been an advisor for Prince Ju before his rebellion, and who was punished by being castrated.

Around 76 BC, Zhang wanted to marry his granddaughter to Bingyi, but his brother Zhang Anshi (張安世), then an important official, opposed his decision, fearing that it would bring trouble to his family. Zhang, instead, invited one of his subordinate eunuchs (who had also been castrated by Emperor Wu), Xu Guanghan (許廣漢), to dinner, and persuaded him to marry his daughter Xu Pingjun to Liu Bingyi. When Xu's wife heard this, she was furious and refused her permission, but because Zhang was Xu's superior, Xu did not dare to renege on the promise. Bingyi and Pingjun were married in a ceremony entirely paid for by Zhang (because Bingyi could not afford the cost). Zhang also paid the bride price. After their marriage, Bingyi heavily depended on his wife's family for support.

Childhood and career as a crown prince

editShi was less than a year old when something very unusual happened to his father. Shi's great-granduncle, Emperor Zhao(漢昭帝), had died that year and the regent, Huo Guang霍光, having been dissatisfied with his initial selection of Prince He of Changyi, deposed Prince He and offered the throne to the commoner Bingyi instead. Bingyi accepted and took the throne as Emperor Xuan. Shi's mother Xu Pingjun was made empress.

This action would cost Empress Xu her life, however, and cost Prince Shi his mother. Huo Guang's wife, Xian (顯), would not be denied her wish of making her daughter Huo Chengjun (霍成君) an empress. In 71 BC, Empress Xu was pregnant when Lady Xian came up with a plot. She bribed Empress Xu's female physician Chunyu Yan (淳于衍), under guise of giving Empress Xu medicine to help ease her pain and control blood flow after she gave birth, to poison Empress Xu. Chunyu did so, and Empress Xu died shortly after she gave birth. Her doctors were initially arrested to investigate whether they cared for the empress properly. Lady Xian, alarmed, informed Huo Guang what had actually happened, and Huo, not having the heart to turn in his wife, instead agreed to Chunyu's release.

In April 70 BC, Emperor Xuan made Huo Chengjun empress. Accustomed to luxury living, her palace expenditures far exceeded the late Empress Xu.

Huo Chengjun becoming empress was a threat to Prince Shi's life. On 24 May 67 BC,[2] Emperor Xuan made the eight-year-old Prince Shi into Crown Prince and awarded Empress Xu's father and Prince Shi's grandfather, Xu Guanghan, the title of Marquess of Ping'en. Huo Guang opposed these actions. Huo's wife, Lady Xian was shocked and displeased, because if her daughter ever had a son, why would he only be forever a prince and not the future emperor. She instructed her daughter to murder the crown prince. Allegedly, Empress Huo did make multiple attempts to do so, but failed each time. Around this time, the emperor also heard rumours that the Huos had murdered Empress Xu, which led him to begin stripping the Huos of actual power, while giving them impressive titles.

In 66 BC, after there had been increasing public rumours that the Huos had murdered Empress Xu, Lady Xian finally revealed to her son and grandnephews that she had, indeed, murdered Empress Xu. In fear of what the emperor might do if he had actual proof, Lady Xian, her son, her grandnephews, and her sons-in-law formed a conspiracy to get the emperor deposed of. The conspiracy was discovered, and the entire Huo clan was executed by Emperor Xuan. Empress Huo was striped of all her titles but not executed, Emperor Xuan decided 12 years later that he wanted her to be exiled, in response, she committed suicide.

What Empress Huo tried to do influenced Emperor Xuan in his choice of the next Emperess. At the time, his favoured consorts were consorts Hua, consorts Zhang, and consorts Wei, each of whom he had children with. He almost settled on Consort Zhang as his new empress. However, he hesitated, remembering how Empress Huo had tried to murder the crown prince. He therefore resolved to making an empress who was childless and kind. He decided on the gentle Consort Wang, and made her empress in 64 BC. Emperor Xuan put Prince Shi in her care, and she cared for him well.

Empress Wang would have a role in Crown Prince Shi's eventual choice of a wife. In the middle of the 50s BC, Consort Sima, the favourite consort of Prince Shi, died from an illness. Prince Shi was grief-stricken and became ill and depressed. Emperor Xuan was concerned, so he had Empress Wang select the most beautiful of the young ladies in waiting and had them sent to Prince Shi. Wang Zhengjun was one of the ladies in waiting chosen. With her, he had his first-born son Liu Ao (劉驁, later Emperor Cheng) c. 51 BC. Prince Ao became Emperor Xuan's favourite grandson and often accompanied him.

During his years as crown prince, Prince Shi did not have a major role in governing the country, given the forceful nature of his father. He was taught the Confucian classics by a succession of Confucian scholars during his pre-teen and teenage years. Prince Shi became a mild-mannered and strict adherent of Confucian principles, unlike his father who made effective use of both Legalist and Confucian principles in his governance. This would bring his father's ire on him.

In 53 BC, when Emperor Xuan and Prince Shi were having dinner, he suggested that Emperor Xuan employ more Confucian officials in key positions. Emperor Xuan became extremely angry and commented that Confucian scholars were impractical and could not be given responsibilities, and further commented that Emperor Yuan's reign would lead to the downfall of the Liu imperial clan, words that would turn out to be prophetic. This would also bring his father to consider changing the succession plans, as he was also disappointed by Prince Shi's general lack of resolve. He considered making Prince Shi's younger brother, Liu Qin, the Prince of Huaiyang, crown prince instead. However, he could not bring himself to do so, remembering how Prince Shi's mother, Empress Xu, was his first love and had been murdered by poisoning, and also how he depended on his father-in-law in his youth. Prince Shi's position therefore was not seriously threatened.

In 49 BC, Emperor Xuan became seriously ill. Before his death, he commissioned his cousin-once-removed Shi Gao (史高), Prince Shi's teacher Xiao Wangzhi (zh:蕭望之), and Xiao's assistant Zhou Kan (周堪) to serve as regents. After he died, Prince Shi ascended the throne as Emperor Yuan.

Reign as emperor

editAs emperor, Emperor Yuan immediately started a regimen of reducing governmental spending, with the objective of reducing the burdens of the people. He also started a program for social assistance to provide stipends for the poor and also for new entrepreneurs. Contrary to his father's governing philosophy, he relied heavily on Confucian scholars and put them into important governmental positions.

In 48 BC, Emperor Yuan made Consort Wang Zhengjun, the mother of his first-born son, Prince Ao, empress. On 17 June 47 BC,[3] he made Prince Ao crown prince.

In 46 BC, alarmed at the high human and monetary cost of occupying Hainan and suppressing the frequent native rebellions, Emperor Yuan decreed that the two commanderies on the island be abandoned. Similarly, in 40 BC, alarmed at the high cost of maintaining imperial temples, he reduced the number of standing temples.

Factionalism

editEarly in Emperor Yuan's administration a factional schism developed, a phenomenon that would plague his entire reign and cause officials to concentrate on infighting rather than effective governance. One faction included mainly Confucian scholars, his teachers, Xiao and Zhou, aligned with an imperial clan member who was also a Confucian scholar, Liu Gengsheng (劉更生, later named Liu Xiang 劉向), and imperial assistant Jin Chang (金敞). The other faction was his cousin-twice-removed Shi, imperial secretary Hong Gong (弘恭) and chief eunuch Shi Xian (石顯). Hong Gong and Shi Xian are recorded as being the Emperor's lovers.[4] Yuan gave them both key administrative positions, which eventually proved disastrous as they plotted the deaths of many officials who opposed them.

The Confucian faction derived their power from the fact that Emperor Yuan trusted and respected their advice. The "court faction" derived their power from their physical closeness to the emperor and their key roles in processing reports and edicts for Emperor Yuan. Policy-wise, the Confucian faction advocated returning to the ancient policies of the early Zhou dynasty, while the court faction advocated keeping the traditions of the Han dynasty.

In 47 BC, Hong and Shi used procedural traps which led to Zhou and Liu being demoted to commoners and Xiao retired. Later that year, the court faction further pressed Xiao into committing suicide. They did this by tricking Emperor Yuan into deciding to have Xiao investigated for inducing his son to make a petition for him, something considered inappropriate. Hong and Shi calculated that Xiao would rather commit suicide than face an investigation, and that was what Xiao did. As a result, the court faction prevailed. Consistent with his personality, Emperor Yuan rebuked Hong and Shi harshly for misleading him and buried Xiao with great honour, but did not punish Hong (who died later that year) and Shi.

In 46 BC, Emperor Yuan summoned Zhou back to his administration and gave him a mid-level office, along with Zhou's student Zhang Meng (張猛, a grandson of the great explorer Zhang Qian). Despite the relatively low positions that Zhou and Zhang had, their advice was highly valued by Emperor Yuan. In 44 BC, he promoted the highly regarded Confucian scholar Gong Yu (貢禹), who tried not to engage himself in factional politics, to the position of vice prime minister, and heeded many of his suggestions to further reduce governmental spending and to encourage the study of Confucianism.

In 43 BC, there were a number of unusual astronomical and meteorological signs that were considered signs of divine disapproval. Shi Xian and his allies, the Xu and Shi clans, alleged that this was a sign of divine disapproval of Zhou and Zhang's policies. Zhou and Zhang were demoted to local posts. In 42 BC, he promoted another Confucian scholar, Kuang Heng (匡衡), to be his key advisor, and Kuang, aware of the fate of the other Confucian scholars, entered into an alliance with Shi Xian to ensure his own safety and power.

In 40 BC, more unusual signs occurred and Emperor Yuan asked the court faction to explain how they could continue to occur if, as they alleged, they were signs of divine disapproval of Zhou and Zhang. They could not, and so Emperor Yuan summoned Zhou and Zhang back to the capital to serve as advisors. However, this would not last long, as Zhou soon died of a stroke, and Shi Xian found an opportunity to falsely accuse Zhang of crimes and forced him to commit suicide.

In 37 BC, another Confucian scholar would try to shake the influence of Shi Xian. He was Jing Fang (京房), who, in addition to studying Confucianism, was also an accomplished fortune teller. (At this time, fortune telling was still considered to be a part of Confucian studies, indeed, a highly honoured part; it was not until several decades later that Confucians began to disfavour fortune telling.) Jing, who had become a trusted advisor of Emperor Yuan after Emperor Yuan greatly favoured his proposed system for examining and promoting regional officials, accused Shi and Shi's assistant Wulu Chongzong (五鹿充宗) of being corrupt and evil. Initially, Emperor Yuan believed him, but took no action against Shi and Wulu. Shi and Wulu soon found out and fought back by accusing Jing of conspiring with Emperor Yuan's brother Liu Qin, the Prince of Huaiyang, and Prince Qin's uncle. As a result, Jing was executed.

Victory over western Xiongnu and complete hegemony over central Asia

editAround the same time, despite Emperor Yuan's general tendency for pacificism, a military confrontation had developed with one branch of Xiongnu, which had split into competing courts ruled by Chanyus Huhanye in the east and Zhizhi in the west. During Emperor Xuan's reign, Chanyu Huhanye had officially submitted to Han as a subject and received Han assistance. Chanyu Zhizhi, then the stronger of the two, tried to maintain a détente with Han by sending his son Juyulishou (駒于利受) to the Han court, but was not so willing to submit, and soon found himself out-powered by the Han-assisted Huhanye. In 49 BC, the last year of Emperor Xuan's reign, Chanyu Zhizhi headed north-west and conquered several Xiyu kingdoms, basing his capital in Jiankun (modern Altay, Xinjiang). From there, he frequently attacked one of the Han's ally, the Wusun.

In 44 BC, Chanyu Zhizhi sent an ambassador to offer tributes to Han, but at the same time demanded that Han deliver his son Juyilishou back to him. Emperor Yuan commissioned a guard commander, Gu Ji (谷吉), to escort Juyilishou. Initially, based on advice from Gong and other key officials, who reasoned that Zhizhi had no real intention to submit and was far away, Emperor Yuan instructed Gu to escort Juyilishou only to the Han borders, and let him travel the remaining journey on his own. Gu reasoned that by escorting Juyilishou all the way to Jiankun, he might be able to persuade Zhizhi to submit, and that he was willing to risk his own life to do so. Emperor Yuan agreed and Gu escorted Juyilishou to Jiankun. Chanyu Zhizhi was not impressed and had Gu executed. Zhizhi then realized that he made a major mistake, and he allianced with Kangju to conquer Wusun, a traditional enemy of Kangju. They repeatedly inflicted heavy victory appon victory against the Wusun over the course several years.

In 36 BC, two Han commanders, Gan Yanshou (甘延壽) and his lieutenant Chen Tang (陳湯), took the initiative start a war on Zhizhi. Zhizhi, after winning many victories over the Wusun and other Xiyu kingdoms, had become exceedingly arrogant, and treated his ally, the king of Kangju, as a subject, he even executed king Kangju's daughter, who had been married to him as part of the alliance. He also forced the other kingdoms in the region, including the powerful Dayuan, to pay him tribute.

Chen felt that Chanyu Zhizhi would eventually become a major threat and devised a plan to eliminate him. Reasoning that Zhizhi was a powerful warrior but lacked the affection to kingdoms that subjected to him, and also that his new capital (on the banks of Lake Balkhash) had only recently been built and lacked strong defences, his plan was to use the colonization forces that the Han army had in Xiyu as well as Wusun forces to advance to and capture Zhizhi's capital. Gan agreed with his plan and wanted to request approval, but Chen feared that civilian officials would disapprove of this plan. Therefore, when Gan fell sick, Chen forged of imperial edicts and requisitioned the colonization military forces as well as forces of the other kingdoms that submitted to Han authority. Once Gan recovered, he tried to reverse Chen's actions, but Chen warned him that it was too late to do so. They then set out (after submitting reports admitting to forging edicts but providing the reasons for doing so), marching along two routes, one force taking a route through Dayuan and the other through Wusun. The forces rejoined when they entered Kangju. They then set a trap for Zhizhi, by pretending that they were running low on supplies, to ward off the possibility that Zhizhi would flee. Zhizhi took the bait and stayed in his capital. The coalition forces soon arrived at his capital and besieged it later killing Chanyu Zhizhi in the subsequent battle.

After this Chanyu Huhanye made an official visit to the Han capital of Chang'an in 33 BC and formally asked to become a "son-in-law of Han". In response, Emperor Yuan gave him five ladies in waiting as a reward, and one of them was the beautiful Wang Zhaojun. Impressed that Emperor Yuan gave him the most beautiful woman that he had ever seen, Huhanye offered to have his forces serve as the northern defence forces for Han, a proposal that Emperor Yuan rejected as ill-advised, but the relationship between Han and Xiongnu thereafter grew stronger.

Succession issues

editEmperor Yuan had two favourite concubines in addition to Empress Wang, Consort Fu (傅昭儀) and Consort Feng Yuan (馮昭儀), each of whom bore him one son. Empress Wang apparently tried to maintain a cordial relationship with both, and she was largely successful, at least as far as Consort Feng was concerned. However, a struggle between Empress Wang and Consort Fu for their sons' heir status erupted.

As Crown Prince Ao grew older, Emperor Yuan became increasingly unhappy with his fitness as imperial heir and impressed with Consort Fu's son, Prince Kang of Dingtao (山陽王劉康). Several incidents led to this situation. One happened in 35 BC, when Emperor Yuan's youngest brother Prince Liu Jing of Zhongshan (中山王劉竟) died. Emperor Yuan became angry because he felt that the teenage Crown Prince Ao was not grieving sufficiently, particularly because Princes Ao and Jing were of similar age and grew up together as playmates, thus showing insufficient respect to Prince Jing. Prince Ao's head of household, Shi Dan (史丹), a relative of Emperor Yuan's grandmother and a senior official respected by Emperor Yuan, managed to convince Emperor Yuan that Crown Prince Ao was trying to stop Emperor Yuan himself from over-grieving, but the seed of dissatisfaction was sown.

As the princes grew older, Emperor Yuan and Prince Kang became closer. They shared a love of and skills in music, particularly the playing of drums. Prince Kang also showed high intelligence and diligence, while Crown Prince Ao was known for drinking and womanizing. When Emperor Yuan grew ill during 35 BC, an illness that he would not recover from, Consort Fu and Prince Kang were often summoned to his sickbed to attend to him, while Empress Wang and Crown Prince Ao rarely were. During his illness, apparently encouraged by Consort Fu, Emperor Yuan reconsidered whether he should make Prince Kang his heir instead. Only the intercession of Shi Dan, who risked his life by stepping onto the carpet of the imperial bed chamber, an act that only the empress was allowed to do (on pain of death) led Emperor Yuan to cease those thoughts. When Emperor Yuan died in 33 BC, Crown Prince Ao ascended the throne (as Emperor Cheng).

Era names

edit- Chuyuan (初元) 48 BC – 44 BC

- Yongguang (永光) 43 BC – 39 BC

- Jianzhao (建昭) 38 BC – 34 BC

- Jingning (竟寧) 33 BC

Family

editConsorts and Issue:

- Empress Xiaoyuan, of the Wang clan (孝元皇后 王氏; 71 BC – 13), personal name Zhengjun (政君)

- Liu Ao, Emperor Xiaocheng (孝成皇帝 劉驁; 51–7 BC), first son

- Zhaoyi, of the Fu clan (定陶共王母 傅氏; d. 2 BC)

- Princess Pingdou (平都公主)

- Liu Kang, Emperor Gong (恭皇 劉康; d. 23 BC), second son

- Zhaoyi, of the Feng clan (昭儀 馮氏; d. 6 BC), personal name Yuan (媛)

- Liu Xing, Prince Xiao of Zhongshan (中山孝王 劉興; d. 8 BC), third son

- Jieyu, of the Wei clan (婕妤 衛氏)

- Princess Pingyang (平陽公主)

- Unknown

- Princess Yingyi (潁邑公主)

- Married Du Ye (杜業)

- Princess Yingyi (潁邑公主)

Ancestry

edit| Liu Ju (128–91 BC) | |||||||||||||||

| Liu Jin (113–91 BC) | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Li (d. 91 BC) | |||||||||||||||

| Emperor Xuan of Han (91–48 BC) | |||||||||||||||

| Wang Naishi (d. 70 BC) | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Dao (d. 91 BC) | |||||||||||||||

| Emperor Yuan of Han (75–33 BC) | |||||||||||||||

| Xu Guanghan (102–61 BC) | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Gong'ai (89–71 BC) | |||||||||||||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ guisi day of the 12th month of the 1st year of the Huang'long era, per vol.27 of Zizhi Tongjian

- ^ wushen day of the 4th month of the 3rd year of the Di'jie era, per vol.25 of Zizhi Tongjian

- ^ dingsi day of the 4th month of the 2nd year of the Chu'yuan era, per vol.28 of Zizhi Tongjian

- ^ B.C., Sima, Qian, approximately 145 B.C.-approximately 86 (1993). Records of the grand historian. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08164-2. OCLC 904733341.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Book of Han, vol. 9.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vols. 24, 25, 27, 28, 29.

- Yap Joseph P. Chapters 11–12. Wars With The Xiongnu - A Translation From Zizhi Tongjian, Author House (2009) ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4