According to the New Testament, a woven crown of thorns (Ancient Greek: στέφανος ἐξ ἀκανθῶν, romanized: stephanos ex akanthōn or ἀκάνθινος στέφανος, akanthinos stephanos) was placed on the head of Jesus during the events leading up to his crucifixion. It was one of the instruments of the Passion, employed by Jesus' captors both to cause him pain and to mock his claim of authority. It is mentioned in the gospels of Matthew (Matthew 27:29),[1] Mark (Mark 15:17)[2] and John (John 19:2, 19:5),[3] and is often alluded to by the early Church Fathers, such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen and others, along with being referenced in the apocryphal Gospel of Peter.[4]

Since at least around the year 400 AD, a relic believed by many[who?] to be the crown of thorns has been venerated. In 1238, the Latin Emperor Baldwin II of Constantinople yielded the relic to French King Louis IX. It was kept in the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris until 15 April 2019, when it was rescued from a fire and moved to the Louvre Museum.[6]

Reproductions of the crown are available to tourists from shops in Jerusalem.[7]

As a relic

editThis section is written like a research paper or scientific journal. (May 2024) |

Jerusalem

editThe three Biblical gospels that mention the crown of thorns do not say what happened to it after the crucifixion. The oldest known mention of the crown already being venerated as a relic was made by Paulinus of Nola, writing after 409,[8] who refers to the crown as a relic that was adored by the faithful (Epistle Macarius in Migne, Patrologia Latina, LXI, 407). Cassiodorus (c. 570) speaks of the crown of thorns among other relics which were "the glory" of the city of Jerusalem. "There", he says, "we may behold the thorny crown, which was only set upon the head of Our Redeemer in order that all the thorns of the world might be gathered together and broken" (Migne, LXX, 621). When Gregory of Tours in De gloria martyri[9] avers that the thorns in the crown still looked green, a freshness which was miraculously renewed each day, he does not much strengthen the historical authenticity of a relic he had not seen, but the Breviary of Jerusalem[10]: 16 (a short text dated to about 530 AD),[10]: iv and the itinerary of Antoninus of Piacenza (6th century)[11]: 18 clearly state that the crown of thorns was then shown in the "Basilica of Mount Zion," although there is uncertainty about the actual site to which the authors refer.[11]: 42 et seq. From these fragments of evidence and others of later date (the "Pilgrimage" of the monk Bernard shows that the relic was still at Mount Zion in 870), it is shown that a purported crown of thorns was venerated at Jerusalem in the first centuries of the common era.

Constantinople

editSome time afterwards, the crown was purportedly moved to Constantinople, the then capital of the Roman empire. Historian François de Mély supposed that the whole crown was transferred from Jerusalem to Constantinople not much earlier than 1063. In any case, Emperor Justinian is stated to have given a thorn to Germain, Bishop of Paris, which was long preserved at Saint-Germain-des-Prés, while the Empress Irene, in 798 or 802, sent Charlemagne several thorns which were deposited by him at Aachen. Eight of these are said to have been there at the consecration of the basilica of Aachen; the subsequent history of several of them can be traced without difficulty: four were given to Saint-Corneille of Compiègne in 877 by Charles the Bald; Hugh the Great, Duke of the Franks, sent one to the Anglo-Saxon King Athelstan in 927, on the occasion of certain marriage negotiations, and it eventually found its way to Malmesbury Abbey; another was presented to a Spanish princess about 1160; and again another was taken to Andechs Abbey in Germany in the year 1200.[12]

France

editIn 1238, Baldwin II, the Latin Emperor of Constantinople, anxious to obtain support for his tottering empire, offered the crown of thorns to Louis IX of France. It was then in the hands of the Venetians as security for a great loan of 13,134 gold pieces, yet it was redeemed and conveyed to Paris where Louis IX built the Sainte-Chapelle, completed in 1248, to receive it. The relic stayed there until the French Revolution, when, after finding a home for a while in the Bibliothèque Nationale, the Concordat of 1801[verification needed] restored it to the Catholic Church, and it was deposited in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris.[13]

The exact plant species used to make the crown is not confirmed. The relic that the church received was examined in the nineteenth century, and it appeared to be a twisted circlet of rushes of Juncus balticus,[14] a plant native to maritime areas of northern Britain, the Baltic region, and Scandinavia.[15][16] The thorns preserved in various other reliquaries appeared to be Ziziphus spina-christi,[14] a plant native to Africa and Southern and Western Asia, and had allegedly been removed from the crown and kept in separate reliquaries since soon after they arrived in France.[14] New reliquaries were provided for the relic, one commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte, another, in jeweled rock crystal and more suitably Gothic, was made to the designs of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. In 2001, when the surviving treasures from the Sainte-Chapelle were exhibited at the Louvre, the chaplet was solemnly presented every Friday at Notre-Dame. Pope John Paul II translated it personally to Sainte-Chapelle during World Youth Day. The relic can be seen only on the first Friday of every month, when it is exhibited for a special veneration Mass, as well as each Friday of Lent[17] (see also Feast of the Crown of Thorns).

Members of the Paris Fire Brigade saved the relic during the Notre-Dame de Paris fire of April 15, 2019.[18]

The Catholic Encyclopedia states:

Authorities are agreed that a sort of helmet of thorns must have been plaited by the Roman soldiers, this band of rushes being employed to hold the thorns together. It seems likely according to M. De Mély, that already at the time when the circlet was brought to Paris the sixty or seventy thorns, which seem to have been afterwards distributed by St. Louis and his successors, had been separated from the band of rushes and were kept in a different reliquary. None of these now remain at Paris. Some small fragments of rush are also preserved [...] at Arras and at Lyons. With regard to the origin and character of the thorns, both tradition and existing remains suggest that they must have come from the bush botanically known as Ziziphus spina-christi, more popularly, the jujube tree. This reaches the height of fifteen or twenty feet and is found growing in abundance by the wayside around Jerusalem. The crooked branches of this shrub are armed with thorns growing in pairs, a straight spine and a curved one commonly occurring together at each point. The relic preserved in the Capella della Spina at Pisa, as well as that at Trier, which though their early history is doubtful and obscure, are among the largest in size, afford a good illustration of this peculiarity.[19]

Third-class relics

editNot all of the reputed holy thorns are considered to be "first-class" relics (relics held to be of the original crown). In Roman Catholic tradition, a relic of the first class is a part of the body of a saint or, in this case, any of the objects used in the Crucifixion that carried the blood of Christ; a relic of the second class is anything known to have been touched or used by a saint; a relic of the third class is a devotional object touched to a first-class relic and, usually, formally blessed as a sacramental.

M. de Mély was able to enumerate more than 700 holy thorns relics.[20] The statement in one medieval obituary that Peter de Aveiro gave to the cathedral of Angers, "unam de spinis quae fuit apposita coronae spinae nostri Redemptoris" ("one of the spines which were attached to the thorny crown of our Redeemer")[20] indicates that many of the thorns were relics of the third class—objects touched to a relic of the first class, in this case some part of the crown itself. Again, even in comparatively modern times, it is not always easy to trace the history of these objects of devotion, as first-class relics were often divided and any number of authentic third-class relics may exist.

Purported remnants

editPrior to the Seventh Crusade, Louis IX of France bought from Baldwin II of Constantinople what was venerated as Jesus' Crown of Thorns. It is kept in Paris to this day, in the Louvre Museum. Individual thorns were given by the French monarch to other European royals: the Holy Thorn Reliquary in the British Museum, for example, containing a single thorn, was made in the 1390s for the French prince Jean, duc de Berry, who is documented as receiving more than one thorn from Charles V and VI, his brother and nephew.[21]

Two "holy thorns" were venerated, one at St. Michael's church in Ghent, the other at Stonyhurst College, both professing to be thorns given by Mary, Queen of Scots to Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of Northumberland.[22][19]

The "Gazetteer of Relics and Miraculous Images" lists the following, following Cruz 1984:

- Belgium: Parochial Church of Wevelgem: a portion of the crown of thorns (since 1561)[23]

- Belgium: Ghent, St. Michael's Church: A thorn from the crown of thorns.[22]

- Czech Republic: Prague, St. Vitus Cathedral: A thorn of the crown of thorns, in the cross at the top of Crown of Saint Wenceslas, part of the Bohemian Crown Jewels

- France: Notre-Dame de Paris: The crown of thorns brought from the Holy Land by Louis IX in the 13th century, from which individual thorns have been given by the French monarchs to other European royals; it is displayed the first Friday of each month and all Fridays in Lent (including Good Friday)

- France: Sainte-Chapelle: A portion of the crown of thorns, brought to the site by Louis IX.

- Germany: Cathedral of Trier: A thorn from the crown of thorns

- Germany: Cologne, Kolumba: A thorn from the crown of thorns, given by Louis IX to the Dominicans of Liège, and a second thorn from the treasure of St. Kolumba, Cologne

- Germany: Elchingen: Church of the former Benedictine Abbey Kloster Elchingen: a thorn brought to the church in 1650/51[24]

- Italy: Rome, Santa Croce in Gerusalemme: Two thorns from the crown of thorns.

- Italy: Rome, Santa Prassede: A small portion of the crown of thorns

- Italy: Pisa, Chiesa di Santa Chiara: A branch with thorns from the crown of thorns

- Italy: Naples, Santa Maria Incoronata: A fragment of the crown of thorns

- Italy: Ariano Irpino, Cathedral: Two Thorns from the crown of thorns

- Portugal: Lisbon, Museum of St. Roque, SCML, Reliquary of the Holy Thorn

- Spain: Oviedo, Cathedral: Five thorns (formerly eight) from the crown of thorns

- Spain: Barcelona, Cathedral: A thorn from the crown of thorns

- Spain: Seville, Iglesia de la Anunciación (Hermandad del Valle): A thorn from the crown of thorns

- United Kingdom: British Museum: Holy Thorn Reliquary (see above), Salting Reliquary, each with a thorn

- United Kingdom: Stanbrook Abbey, Worcester: A thorn from the crown of thorns

- United Kingdom: Stonyhurst College, Lancashire: A thorn from the crown of thorns.[22]

- United States: St. Anthony's Chapel, Pittsburgh: A thorn from the crown of thorns

- Ukraine: Odesa, St. Prophet Elijah Monastery: A fragment of a thorn of the crown of thorns

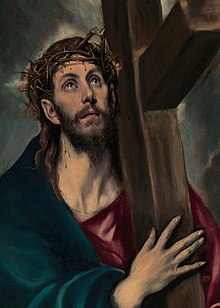

Iconography

editThe appearance of the crown of thorns in art, notably upon the head of Christ in representations of the Crucifixion or the subject Ecce Homo, arises after the time of St. Louis and the building of the Sainte-Chapelle. The Catholic Encyclopedia reported that some archaeologists had professed to discover a figure of the crown of thorns in the circle which sometimes surrounds the chi-rho emblem on early Christian sarcophagi, but the compilers considered that it seemed to be quite as probable that this was only meant for a laurel wreath.

The image of the crown of thorns is often used symbolically to contrast with earthly monarchical crowns. In the symbolism of King Charles the Martyr, the executed English King Charles I is depicted putting aside his earthly crown to take up the crown of thorns, as in William Marshall's print Eikon Basilike. This contrast appears elsewhere in art, for example in Frank Dicksee's painting The Two Crowns.[25]

Catholic missionaries likened several parts of the Passiflora plant to elements of the Passion: the flower's radial filaments, which can number more than a hundred and vary from flower to flower, represent the crown of thorns.[26] Carnations symbolize the passion as they represent the crown of thorns.

Photo gallery

edit-

Reliquary made in 1806, commissioned by Napoleon, preserved at Notre-Dame Cathedral.

-

A second reliquary from 1862, designed by Viollet-le-Duc preserved at Notre-Dame Cathedral.

-

Detail of the 1862 reliquary.

-

The Sainte-Chapelle, built to house the Passion Relics.

-

William Marshall's print depicting King Charles I taking up the crown of thorns

-

Bronze bust of Jesus with in the Monumental cemetery of Brescia.

-

Bust of Christ by Johann Baptist Walpoth 1932.

Criticism of the veneration of the crown of thorns

editA critique of the adoration of the crown of thorns was set forth in 1543 by John Calvin in the work Treatise on Relics. He described numerous parts of the crown of thorns known to him, located in different cities.[27] Based on a large number of parts of the crown of thorns, Calvin wrote:

In regard to the Crown of thorns, it would seem that its twigs had been planted that they might grow again. Otherwise I know not how it could have attained to such a size. First, a third part of it is at Paris, in the Holy Chapel, and then at Rome there are three thorns in Santa Croce, and some portion also in St. Eustathius. At Sienna, I know not how many thorns, at Vincennes one, at Bourges five, at Besançon, in the church of St. John, three, and as many at Koenigsberg. At the church of St. Salvator, in Spain, are several, but how many I know not; at Compostella, in the church of St. Jago, two; in Vivarais, three; also at Toulouse, Mascon, Charrox in Poictou, St. Clair, Sanflor, San Maximin in Provence, in the monastery of Selles, and also in the church of St. Martin at Noyon, each place having a single thorn. But if diligent search were made, the number might be increased fourfold. It is most evident that there must here be falsehood and imposition. How will the truth be ascertained? It ought, moreover, to be observed, that in the ancient Church it was never known what had become of that crown. Hence it is easy to conclude, that the first twig of that now shown grew many years after our Saviour's death.[28]

See also

edit- Relics associated with Jesus

- Angel with the Crown of Thorns – Sculpture by Gianlorenzo Bernini

- Christ Crowned with Thorns (disambiguation) – Several works of art

- Euphorbia milii

- Jesus, King of the Jews

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Man of Sorrows

- Paliurus spina-christi

- Radiant crown

- Solar symbol

- Sorrowful Mysteries

- Thorncrown Chapel

Notes

edit- ^ Matthew 27:29

- ^ Mark 15:17

- ^ John 19:2, John 19:5

- ^ Walter Richard (1894). The Gospel According to Peter: A Study. Longmans, Green. p. 7. Retrieved 2022-04-02.

- ^ Davisson, Darrell D (2004). Kleinhenz, Christopher (ed.). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 955. ISBN 9780415939294.

- ^ Clicquot, Athénaïs (9 September 2019). "Notre-Dame: la couronne d'épines à nouveau présentée à la vénération des fidèles" (in French). Retrieved 2020-09-15.

- ^ "Carod-Rovira consigue que retiren la bandera española en un acto de la Generalitat en Israel". www.elmundo.es (in European Spanish). 21 May 2005. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

Al salir del Santo Sepulcro, la iglesia de referencia del cristianismo, el 'president' ha fotografiado a Carod-Rovira con una corona de espinas de una tienda para turistas.

[After leaving the Holy Sepulchre, the church of reference for Christianity, the president has photographed Carod-Rovira with a crown of thorns from a tourist shop.] - ^ Wall, J. Charles (2016). Relics from the Crucifixion: Where They Went and How They Got There. Sophia Institute Press. p. 95. ISBN 9781622823277. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ Published in Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores Merovingenses", I, 492.

- ^ a b The Epitome of S. Eucherius About Certain Holy Places: And the Breviary or Short Description of Jerusalem. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society. 1896.

- ^ a b Stewart, Aubrey; Wilson, CW, eds. (1896). Of the Holy Places Visited by Antoninus Martyr (Circ. 560–570 A.D.). London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ History and Authenticity of the Relic of the Crown of Thorns (2019). Mystogogy Resource Center.

- ^ "France: Kissing the original Crown of Thorns worn by Jesus". Minor Sights. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ^ a b c Cherry, 22

- ^ P.A. Stroh; T. A. Humphrey; R.J. Burkmar; O.L. Pescott; D.B. Roy; K.J. Walker (eds.). "Juncus balticus Willd". BSBI Online Plant Atlas 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ "Juncus balticus Willd". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ "France: Kissing the original Crown of Thorns". Minor Sights. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ^ ""Computer glitch" may be behind Notre Dame Cathedral fire, rector says - live updates". CBS News. 19 April 2019.

- ^ a b Thurston, Herbert (1908). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4.

- ^ a b "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Crown of Thorns". New Advent. Retrieved 2024-03-29.

- ^ Cherry 2010, p. 22–23.

- ^ a b c John Morris, Life of Father Gerard (London, 1881), pp. 126-131.

- ^ Vandaele, Luc (20 March 2006). "In de ban van de Heilige Doorn (Wevelgem)". Het Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Deger, Manfred (24 August 2011). "Glaube: Der Dorn und die Bruderschaft". Augsburger Allgemeine (in German). Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ The Two Crowns

- ^ Roger L. Hammer (6 January 2015). Everglades Wildflowers: A Field Guide to Wildflowers of the Historic Everglades, including Big Cypress, Corkscrew, and Fakahatchee Swamps. Falcon Guides. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-1-4930-1459-0.

- ^ Mullett, Michael (19 May 2011). John Calvin. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 105. ISBN 9780415476980.

- ^ Calvin, John (1844). – via Wikisource., translated by Henry Beveridge

References

edit- Cherry, John (2010). The Holy Thorn reliquary. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0714128207.

- Westerson, Jeri (2009). Serpent in the Thorns; A Medieval Noir. New York: Minotaur Books. ISBN 978-0312649449. (Fiction referencing the crown of thorns.)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Thurston, Herbert (1908). "Crown of Thorns". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4.