Jacques Cujas (or Cujacius) (Toulouse, 1522 – Bourges, 4 October 1590) was a French legal expert. He was prominent among the legal humanists or mos gallicus school, which sought to abandon the work of the medieval Commentators and concentrate on ascertaining the correct text and social context of the original works of Roman law.

Jacques Cujas | |

|---|---|

Jacques de Cujas by an anonymous painter around 1580 | |

| Born | 1522 |

| Died | October 4, 1590 (aged 67–68) |

Biography

editHe was born at Toulouse, where his father, surnamed Cujaus, was a fuller. Having taught himself Latin and Greek, he studied law under Arnaud du Ferrièr, then professor at Toulouse, and rapidly gained a great reputation as a lecturer on Justinian. In 1554 he was appointed professor of law at Cahors, and about a year after Michel de l'Hôpital called him to Bourges. François Douaren (Franciscus Duarenus), who also held a professorship at Bourges, stirred up the students against the new professor, and Cujas was glad to accept an invitation he had received to the University of Valence.[1]

Recalled to Bourges at the death of Duaren in 1559, he remained there until 1567, when he returned to Valence. There he gained a European reputation, and collected students from all parts of the continent, among whom were Joseph Scaliger and Jacques Auguste de Thou. In 1573 King Charles IX of France appointed Cujas counsellor to the parlement of Grenoble, and in the following year a pension was bestowed on him by Henry III. Margaret of Savoy persuaded him to move to Turin; but after a few months (1575) he returned to his old place at Bourges. The religious wars drove him out. He was called by the king to Paris, and permission was granted him by the parlement to lecture on civil law in the university there. A year later, he finally took up residence at Bourges, where he remained until his death in 1590, in spite of a handsome offer made him by pope Gregory XIII in 1584 to attract him to Bologna.[1]

Works

editThe life of Cujas was altogether that of a scholar and teacher. In the religious wars which filled all the thoughts of his contemporaries he steadfastly refused to take any part. Nihil hoc ad edictum praetoris, "this has nothing to do with the edict of the praetor," was his usual answer to those who spoke to him on the subject. His claim as a jurisconsult consisted in the fact that he turned from whom he considered the "ignorant" commentators on Roman law to the Roman law itself. He consulted a very large number of manuscripts, of which he had collected more than 500 in his own library; but he left orders in his will that his library should be divided among a number of purchasers, and so his collection was scattered and in great part lost.[1]

His emendations, of which a large number were published under the title of Observationes et emendationes, were not confined to lawbooks, but extended to many of the Latin and Greek classical authors. In jurisprudence his study was far from being devoted solely to Justinian; he recovered part of the Theodosian Code, with explanations and he procured the manuscript of the Basilika.[2]

He also composed a commentary on the Consuetudines Feudorum, and on some books of the Decretals. In the Paratitla, or summaries which he made of the Digest, and particularly of the Code of Justinian, he condensed into short axioms the elementary principles of law, and gave definitions remarkable for their clarity and precision.[3]

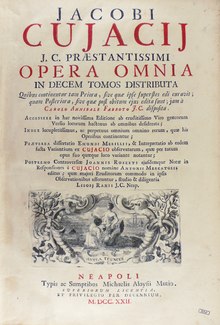

In his lifetime Cujas published an edition of his works (Neville, 1577). It is incomplete. The edition of Colombet (1634) is also incomplete. Charles Annibal Fabrot, however, collected the complete works of Cujas in the edition which he published at Paris (1658), Naples and Venice.[3]

Personality

editHis lessons, which he never dictated, were continuous discourses, for which he made no other preparation than that of profound meditation on the subjects to be discussed. He was impatient of interruptions and upon the least noise he would instantly quit the chair and retire. He was strongly attached to his pupils, and Joseph Justus Scaliger affirms that he lost more than 4000 livres by lending money to the more needy of them.[3]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 614.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 614–615.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 615.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cujas, Jacques". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 614–615.

References

edit- Papire-Masson, Vie de Cujas (Paris, 1590).

- Gabor Hamza, "Le développement du droit privé eurpéen" (Budapest, 2005).

- Gabor Hamza, "Entstehung und Entwicklung der modernen Privatrechtsordnungen und die römischrechtliche Tradition" (Budapest, 2009)

- Gabor Hamza, "Origine e sviluppo degli ordinamenti giusprivatistici moderni in base alla tradizione del diritto moderno" (Santiago de Compostela, 2013)

External links

edit- Phillipson, Coleman (1913). "JACQUE CUJAS". In Macdonell, John; Manson, Edward William Donoghue (eds.). Great Jurists of the World. London: John Murray. pp. 83–. Retrieved 9 March 2019 – via Internet Archive.