This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2023) |

The culture of Ireland includes the art, music, dance, folklore, traditional clothing, language, literature, cuisine and sport associated with Ireland and the Irish people. For most of its recorded history, the country’s culture has been primarily Gaelic (see Gaelic Ireland). Strong family values, wit and an appreciation for tradition are commonly associated with Irish culture.

Irish culture has been greatly influenced by Christianity, most notably by the Roman Catholic Church, and religion plays a significant role in the lives of many Irish people. Today, there are often notable cultural differences between those of Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox background. References to God can be found in spoken Irish, notably exemplified by the Irish equivalent of “Hello” — “Dia dhuit” (literally: "God be with you").[2]

Irish culture has Celtic, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, French and Spanish[3][4][5] influences. It also has British influences, primarily due to over eight centuries of British rule in Ireland, which suppressed numerous aspects of Irish culture.[6][7][8] The Vikings first invaded Ireland in the 8th century, from Denmark, Norway and Sweden in modern-day Scandinavia. They had a significant influence on Ireland’s material culture at the time.[9] The Normans invaded Ireland in the 12th century, bringing British and French influences. Additionally, Irish Travellers have had some influence on the broader cultural tapestry of Ireland, introducing nomadic traditions and other cultural practices. In recent decades, Ireland has also to some degree been influenced by migration from the former Eastern Bloc.[10][11][12]

Due to large-scale emigration from Ireland, Irish culture has a wide reach in the world, and festivals such as Saint Patrick's Day (Irish: Lá Fhéile Pádraig) and Halloween (which finds its roots in the Gaelic festival Samhain) are celebrated across much of the globe.[13] Irish culture has to some extent been inherited and modified by the Irish diaspora, which in turn has influenced the home country. Moreover, the culture of Ireland is to some degree influenced by its native folklore and legends, such as those detailed in Lebor Gabála Érenn.[14]

Farming and rural tradition

editAs archaeological evidence from sites such as the Céide Fields in County Mayo and Lough Gur in County Limerick demonstrates, the farm in Ireland is an activity that goes back to the Neolithic, about 6,000 years ago. Before this, the first settlers of the island of Ireland after the last Ice Age were a new wave of cavemen and the Mesolithic period.[15] In historic times, texts such as the Táin Bó Cúailinge show a society in which cows represented a primary source of wealth and status. Little of this had changed by the time of the Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th century. Giraldus Cambrensis portrayed a Gaelic society in which cattle farming and transhumance was the norm.

Townlands, villages, parishes and counties

editThe Normans replaced traditional clan land management (under Brehon Law) with the manorial system of land tenure and social organisation. This led to the imposition of the village, parish and county over the native system of townlands. In general, a parish was a civil and religious unit with a manor, a village and a church at its centre. Each parish incorporated one or more existing townlands into its boundaries. With the gradual extension of English feudalism over the island, the Irish county structure came into existence and was completed in 1610.[citation needed] These structures are still of vital importance in the daily life of Irish communities. Apart from the religious significance of the parish, most rural postal addresses consist of house and townland names. The village and parish are key focal points around which sporting rivalries and other forms of local identity are built and most people feel a strong sense of loyalty to their native county, a loyalty which also often has its clearest expression on the sports field.[citation needed]

Land ownership and "land hunger"

editWith the Tudor Elizabethan English conquest in the 16th-17th centuries, the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, and the organized plantations of English Tudor, and later Scottish, colonists, the Scottish confined to what's now mostly Northern Ireland, the patterns of land ownership in Ireland were altered greatly. The old order of transhumance and open range cattle breeding died out to be replaced by a structure of great landed estates, small tenant farmers with more or less precarious hold on their leases, and a mass of landless labourers. This situation continued up to the end of the 19th century, when the agitation of the Land League began to bring about land reform. In this process of reform, the former tenants and labourers became land owners, with the great estates being broken up into small- and medium-sized farms and smallholdings. The process continued well into the 20th century with the work of the Irish Land Commission. This contrasted with Britain, where many of the big estates were left intact. One consequence of this is the widely recognised cultural phenomenon of "land hunger" amongst the new class of Irish farmer. In general, this means that farming families will do almost anything to retain land ownership within the family unit, with the greatest ambition possible being the acquisition of additional land. Another is that hillwalkers in Ireland today are more constrained than their counterparts in Britain, as it is more difficult to agree rights of way with so many small farmers involved on a given route, rather than with just one landowner.

Irish Travellers

editIrish Travellers (Shelta: Mincéirí) are known for their historically nomadic lifestyle; residing in ornamented barrel top wagons, they would traverse predominantly rural areas of the island. Their propensity for rural living was influenced by a variety of factors including cultural traditions, a desire for privacy and autonomy, work opportunities and their fondness of the natural world. Travellers would often find work in rural areas, predominantly in farming, horse trading and tinsmithing. While many Mincéirí in contemporary Ireland are now settled, including in urban areas, they often maintain rural traditions such as horseback riding, and attend traditional fairs and festivals in the countryside.[16][17]

Holidays and festivals

editChristmas in Ireland has several local traditions. On 26 December (St. Stephen's Day), there is a custom of "Wrenboys"[18] who call door to door with an arrangement of assorted material (which changes in different localities) to represent a dead wren "caught in the furze", as their rhyme goes.

The national holiday in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland is Saint Patrick's Day, that falls on the date 17 March and is marked by parades and festivals in cities and towns across the island of Ireland, and by the Irish diaspora around the world. The festival is in remembrance of Saint Patrick, the most significant of Ireland's three patron saints. Pious legend credits Patrick with the banishing of the snakes from the island, and the legend also credits Patrick with teaching the Irish about the concept of the Trinity by showing people the shamrock, a 3-leaved clover, using it to highlight the Christian belief of 'three divine persons in the one God'.

In Northern Ireland The Twelfth of July, or Orangemen's Day, commemorates William III's victory at the Battle of the Boyne. A public holiday, it is celebrated by Irish Protestants, in particular Ulster Protestants, the vast majority of whom live in Northern Ireland. It is notable for the numerous parades organised by the Orange Order which take place throughout Northern Ireland. These parades are colourful affairs with Orange Banners and sashes on display and include music in the form of traditional songs such as "The Sash" and "Derry's Walls" performed by a mixture of pipe, flute, accordion, and brass marching bands. The Twelfth remains controversial as many in Northern Ireland's large and majority-nationalist Catholic community see the holiday, celebrating a victory over Catholics that ensured the continued establishment of a Protestant Ascendancy, as triumphalist, supremacist, and an assertion of British and Ulster Protestant dominance.[19][20][21][22][23][24]

The 1st of February, known as St. Brigid's Day (after St. Brigid, one of the patron saints of Ireland) or Imbolc, also does not have its origins in Christianity, being instead another religious observance superimposed at the beginning of spring. St. Brigid’s Day is the only official public holiday named after a woman in Ireland. The Brigid's cross made from rushes represents a pre-Christian solar wheel.[25][26]

Other pre-Christian festivals, whose names survive as Irish month names, are Bealtaine (May), Lúnasa (August) and Samhain (November). The last is still widely observed as Halloween which is celebrated all over the world, including in the United States followed by All Saints' Day, another Christian holiday associated with a traditional one. Important church holidays include Easter, and various Marian observances.[citation needed]

Religion

editChristianity was brought to Ireland during or prior to the 5th century[27] and its early history among the Irish is in particular associated with Saint Patrick, who is generally considered Ireland's leading patron saint.[28] The Celtic festival of Samhain, not to be confused with Halloween, originated in Ireland and a reconstructed version is celebrated by some across the globe.[29]

Ireland is a place where religion and religious practice have long been held in high esteem. The majority of people on the island are Roman Catholics;[30] however, there are significant Protestant and Orthodox minorities. Protestants are mostly concentrated in Northern Ireland, where they long made up a plurality of the population.[31] The three main Protestant denominations on the island are the Anglican Church of Ireland, the Presbyterian Church in Ireland and the Methodist Church in Ireland. These are also joined by numerous other smaller denominations including Baptists, several American gospel groups and the Salvation Army. Orthodox Christianity also has a notable presence in Ireland, where it has been the fastest growing religion since 1991, largely due to immigration from Eastern Europe.[32] Other minority denominations of Christianity include Jehovah's Witnesses and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS). In addition to the Christian denominations there are centres for Buddhists, Hindus, Baháʼís, Pagans and for people of the Islamic and Jewish faiths.

In the 2021 Census, of those in the Republic of Ireland that stated their religious identity, 81.6% identified as Christian; 68.8% as Roman Catholic, 4.2% as Protestant, 2.1% as Orthodox, 0.7% as other Christians, while 1.6% identified as Muslim, 0.7% as Hindu, 14.8% as having no religion and 7.1% not stating their religious identity.[31] Amongst the Republic's Roman Catholics, weekly church attendance has declined sharply over the past few decades, from 87% in 1981, to 60% in 1998, to 30% in 2021.[33] Still, this remains one of the higher attendance rates in Europe.[34] The decline is said to be linked to reports of Catholic Church sexual abuse cases in Ireland.

Mythology and folklore

editHighly respected in Ireland historically were the stories of heroes such as Fionn mac Cumhaill and his followers, the Fianna, from the Fenian cycle, and Cuchulain from the Ulster Cycle, along with some of the High Kings. Legend has it that Fionn mac Cumhaill built the Giant's Causeway as a line of stepping-stones to Scotland, not to get his feet wet while seeking to fight an ugly Scottish giant. He also is said to have once scooped up part of Ireland to fling it at a rival, but it missed and landed in the Irish Sea – the clump becoming the Isle of Man, a pebble Rockall, and the void left behind filling as Lough Neagh. The Irish king Brian Boru who ended the domination of the so-called High Kingship of Ireland by the Uí Néill, is part of the historical cycle. The Irish princess Iseult is the adulterous lover of Tristan in the Arthurian romance and tragedy Tristan and Iseult. The many legends of ancient Ireland were captured by many collators, including Lady Gregory in two volumes with forewords by W. B. Yeats. These stories depict a status for Celtic women in ancient times somewhat different from many other cultures of the period.[citation needed]

According to the tales, the leprechaun is a mischievous fairy type creature in emerald green clothing who when not playing tricks spend all their time busily making shoes; he is said to have a pot of gold hidden at the end of the rainbow and if ever captured by a human has the magical power to grant three wishes in exchange for release.[35] There are also tales of the pooka and banshees, among others.[citation needed]

Halloween is a traditional and much celebrated holiday in Ireland on the night of 31 October.[36] Supposedly the first evidence of the word halloween is found in a 16th-century Scottish document as a shortening for All-Hallows-Eve,[37] and according to some historians it has its roots in the gaelic festival Samhain, where the Gaels believed the border between this world and the otherworld became thin, and the dead would revisit the mortal world.[38] In Ireland, traditional Halloween customs include; Guising – children disguised in costume going from door to door requesting food or coins – which became practice by the late 19th century,[39][40] turnips hollowed-out and carved with faces to make lanterns,[39] holding parties where games such as apple bobbing are played.[41] Other practices in Ireland include lighting bonfires, and having firework displays.[42] Mass transatlantic Irish and Scottish immigration in the 19th century popularised Halloween in North America.[43]

Literature and the arts

editFor a comparatively small place, the island of Ireland has made a disproportionately large contribution to world literature in all its branches, in both the Irish and English languages. The island's most widely known literary works are undoubtedly in English. Particularly famous examples of such works are those of James Joyce, Bram Stoker, Jonathan Swift, Oscar Wilde and Ireland's four winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature; William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett and Seamus Heaney. Three of the four Nobel prize winners were born in Dublin (Heaney being the exception, having lived in Dublin but being born in County Londonderry), making it the birthplace of more Nobel literary laureates than any other city in the world.[44] The Irish language has the third oldest literature in Europe (after Greek and Latin),[citation needed] the most significant body of written literature (both ancient and recent) of any Celtic language, as well as a strong oral tradition of legends and poetry. Poetry in Irish represents the oldest vernacular poetry in Europe, with the earliest examples dating from the 6th century.

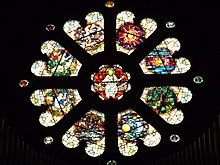

The early history of Irish visual art is generally considered to begin with early carvings found at sites such as Newgrange and is traced through Bronze Age artefacts, particularly ornamental gold objects, and the Celtic brooches and illuminated manuscripts of the "Insular" Early Medieval period. During the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, a strong indigenous tradition of painting emerged, including such figures as John Butler Yeats, William Orpen, Jack Yeats and Louis le Brocquy.

The Irish tradition of folk music and dance is also widely known, and both were redefined in the 1950s. In the middle years of the 20th century, as Irish society was attempting to modernise, traditional Irish music fell out of favour to some extent, especially in urban areas. Young people at this time tended to look to Britain and, particularly, the United States as models of progress and jazz and rock and roll became extremely popular. During the 1960s, and inspired by the American folk music movement, there was a revival of interest in the Irish tradition. This revival was inspired by groups like The Dubliners, the Clancy Brothers and Sweeney's Men and individuals like Seán Ó Riada. The annual Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann is the largest festival of Irish music in Ireland. Groups and musicians like Horslips, Van Morrison and even Thin Lizzy incorporated elements of traditional music into a rock idiom to form a unique new sound. During the 1970s and 1980s, the distinction between traditional and rock and pop musicians became blurred, with many individuals regularly crossing over between these styles of playing as a matter of course. This trend can be seen more recently in the work of bands like U2, Snow Patrol, The Cranberries, The Undertones and The Corrs, and individual artists such as Enya.[citation needed]

| W. B. Yeats (1865–1939) |

George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) |

Samuel Beckett (1906–1989) |

Seamus Heaney (1939–2013) |

|---|---|---|---|

Languages

editThis section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Irish status in Northern Ireland. (February 2023) |

Irish and English are the most widely spoken languages in Ireland. English is the most widely spoken language on the island overall, and Irish is spoken as a first language only by a small minority, primarily, though not exclusively, in the government-defined Gaeltacht regions in the Republic. A larger minority have Irish as a second language, with 40.6% of people in the Republic of Ireland claiming some ability to speak the language in the 2011 census.[45] Article 8 of the Constitution of Ireland states that Irish is the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland.[46] English in turn is recognised as the State's second official language.[46] Hiberno-English, the dialect of English spoken in most of the Republic of Ireland, has been greatly influenced by Irish.[47]

In Northern Ireland, English is a de facto official language, with Ulster English being common. In 2022, the Irish language received official language status in Northern Ireland as a result of the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act, with Ulster Scots receiving minority language status.[48] In addition, these languages have recognition under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, with 8.1% claiming some ability in Ulster Scots and 10.7% in Irish.[49] In addition, the dialect and accent of the people of Northern Ireland is noticeably different from that of the majority in the Republic of Ireland, being influenced by Ulster Scots and Northern Ireland's proximity to Scotland.

Several other languages are spoken on the island, including Shelta, a mixture of Irish, Romani and English, spoken widely by Travellers. Two sign languages have also been developed on the island, Northern Irish Sign Language and Irish Sign Language; they have quite different bases.

Some other languages have entered Ireland with immigrants – for example, Polish is now the second most widely spoken language in Ireland after English, Irish being the third most commonly spoken language.[50]

Food and drink

editPre-Medieval Ireland

editThere are many references to food and drink in early Irish literature. Honey seems to have been widely eaten and used in the making of mead. The old stories also contain many references to banquets, although these may well be greatly exaggerated and provide little insight into everyday diet. There are also many references to fulacht fia, which are archaeological sites commonly believed to have once been used for cooking venison. The fulacht fia have holes or troughs in the ground which can be filled with water. Meat can then be cooked by placing hot stones in the trough until the water boils. Many fulach fia sites have been identified across the island of Ireland, and some of them appear to have been in use up to the 17th century.

Excavations at the Viking settlement in the Wood Quay area of Dublin have produced a significant amount of information on the diet of the inhabitants of the town. The main animals eaten were cattle, sheep and pigs, with pigs being the most common. This popularity extended down to modern times in Ireland. Poultry and wild geese as well as fish and shellfish were also common, as were a wide range of native berries and nuts, especially hazel. The seeds of knotgrass and goosefoot were widely present and may have been used to make a porridge.

Early-modern Ireland

editThe Tudor conquest of Ireland led to significant changes in the Irish diet, as it introduced a new agro-alimentary system of intensive grain-based agriculture and led to large areas of land being turned over to grain production. The potato was introduced into Ireland in the second half of the 16th century, as a result of the Columbian exchange, initially as a garden crop; it eventually came to serve as the main food field crop of the tenant and labouring classes, which formed a majority of the population. Ireland also grew large quantities of corned beef, though the vast majority of it was exported.[51] The over-reliance on potatoes as a staple crop in Irish cuisine meant that the people of Ireland were vulnerable to poor potato harvests. The Irish Famine of 1740 was the result of extreme cold weather, but the Great Famine of 1845–1849 was caused by potato blight which spread throughout the Irish crop which consisted largely of a single variety, the Lumper. During the famine, approximately one million people died and a million more emigrated elsewhere.[52][53]

Modern Ireland

editIn the 21st century, the modern selection of foods common to Western cultures has also to some extent been adopted in Ireland. Both US fast food culture and continental European dishes have influenced the country, along with other world dishes introduced in a similar fashion to the Western world. In addition to Irish food, meals eaten in Ireland may include pizza, curry and Chinese food, with some west African dishes making an appearance lately. Supermarket shelves now contain ingredients for, among others, traditional, Polish, Mexican, Indian and Chinese dishes.

The proliferation of fast food has led to increasing public health problems including obesity, and one of the highest rates of heart disease in the world.[54] In Ireland, the Full Irish has been particularly cited as being a major source for a higher incidence of cardiac problems, quoted as being a "heart attack on a plate". All the ingredients are fried, although more recently the trend is to grill as many of the ingredients as possible.

In tandem with these developments, the last quarter of the century saw the emergence of a new Irish cuisine based on traditional ingredients handled in new ways. This cuisine is based on fresh vegetables, fish, especially salmon and trout, oysters and other shellfish, traditional soda bread, the wide range of hand-made cheeses that are now being made across the country, and, of course, the potato. Traditional dishes, such as the Irish stew, Dublin coddle, the Irish breakfast and potato bread, have enjoyed a resurgence. Schools like the Ballymaloe Cookery School have emerged to cater for the associated increased interest in cooking with traditional ingredients.

- Representative Irish foods

-

Barmbrack (Bairín breac)

-

Irish stew (Stobhach)

-

Irish Soda bread (áran sóide) served with Irish butter

-

Seafood chowder

-

Beef and mushroom boxty

-

Irish cream cheesecake

Pub culture

editPub culture term refers to the habit amongst Irish people of frequenting public houses (pubs). It extends beyond mere alcohol consumption (upon which it is not dependent), encompassing a variety of social traditions. Pubs vary widely according to the clientele they serve, and the area they are in. Best known, and loved amongst tourists is the traditional pub, with its traditional Irish music (or "trad music") often performed live, tavern-like warmness, memorabilia and traditional Irish ornamentation. Often such pubs will also serve Irish food, particularly during the day. Typically pubs are important meeting places, where people can gather and meet their neighbours and friends in a relaxed atmosphere; similar to the café cultures of other countries. Many modern pubs, not necessarily traditional, still emulate traditional pubs, only perhaps substituting traditional music for a DJ or non-traditional live music.

Many larger pubs in cities eschew such trappings entirely, opting for loud music, and focusing more on the consumption of drinks, which is not a focus of traditional Irish culture. Such venues are popular "pre-clubbing" locations. "Clubbing" has become a popular phenomenon amongst young people in Ireland during the celtic tiger years. Clubs usually vary in terms of the type of music played, and the target audience. Belfast has a unique underground club scene taking place in settings such as churches, zoos, and crematoriums. The underground scene is mainly orchestrated by DJ Christopher McCafferty .[55] [56]

A significant recent change to pub culture in the Republic of Ireland has been the introduction of a smoking ban, in all workplaces, which includes pubs and restaurants. Ireland was the first country in the world to implement such a ban which was introduced on 29 March 2004.[57] A majority of the population support the ban, including a significant percentage of smokers. Nevertheless, the atmosphere in pubs has changed greatly as a result, and debate continues on whether it has boosted or lowered sales, although this is often blamed on the ever-increasing prices, or whether it is a "good thing" or a "bad thing". A similar ban, under the Smoking (Northern Ireland) Order 2006, came into effect in Northern Ireland on 30 April 2007.[58]

National and international organisations have labelled Ireland as having a problem with over-consumption of alcohol. In the late 1980s alcohol consumption accounted for nearly 25% of all hospital admissions. While this figure has been decreasing steadily, as of 2007, approximately 13% of overall hospital admissions were alcohol related.[59] In 2003, Ireland had the second-highest per capita alcohol consumption in the world, just below Luxembourg at 13.5 litres (per person 15 or more years old), according to the OECD Health Data 2009 survey.[60] According to the latest OECD figures, alcohol consumption in Ireland has dropped from 11.5 litres per adult in 2012 to 10.6 litres per adult in 2013. However, research showed that in 2013, 75% of alcohol was consumed as part of a drinking session where the person drank six or more standard units (which equates to three or more pints of beer). This meets the Health Service Executive's definition of binge drinking.[61]

Sport

editSport on the island of Ireland is popular and widespread. A wide variety of sports are played throughout the island, with the most popular being Gaelic football, hurling, soccer, rugby union, and golf. Four sports account for over 80% of event attendance: Gaelic football is the most popular sport in Ireland in terms of match attendance and community involvement, and represents 34% of total sports attendances at events in the Republic of Ireland and abroad, followed by hurling at 23%, soccer at 16% and rugby at 8%.[62][63] and the All-Ireland Football Final is the most watched event in Ireland's sporting calendar.[64]

Swimming, golf, aerobics, soccer, cycling, Gaelic football, and billiards, pool and snooker, are the sporting activities with the highest levels of playing participation.[65] Other sports with material playing populations, including at school level, include tennis, hockey, pitch and putt, rugby, basketball, boxing, cricket and squash. Significant numbers attend horse racing meetings, and Ireland breeds and trains many racehorses; greyhound racing also has dedicated racecourses.

Soccer is the most popular sport involving national teams. The success of the Ireland team at the 1990 FIFA World Cup saw 500,000 fans in Dublin to welcome the team home.[66] The team's song "Put 'Em Under Pressure" topped the Irish charts for 13 weeks.[67]

In Ireland most sports, including rugby union, Gaelic football, hurling and handball, cycling and golf, are organised on an all-island basis, with, where relevant, a single team representing the island of Ireland in international competitions. A few sports, such as soccer, have separate organising bodies in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Traditionally, those in the North who identify as Irish, predominantly Catholics and nationalists, support the Republic of Ireland team.[68] At the Olympics, a person from Northern Ireland can choose to represent either the Great Britain team or the Ireland team. Also as Northern Ireland is a Home Nation of the United Kingdom it also sends a Northern Ireland Team to the Commonwealth Games every four years.

Media

editIn the Republic of Ireland there are several daily newspapers, including the Irish Independent, The Irish Examiner, The Irish Times, The Star, The Evening Herald, Daily Ireland, the Irish Sun, and the Irish language Lá Nua. The best selling of these is the Irish Independent, which is published in both tabloid and broadsheet form. The Irish Times is Ireland's newspaper of record.

The Sunday market is quite saturated with many British publications. The leading Sunday newspaper in terms of circulation is The Sunday Independent. Other popular papers include The Sunday Times, The Sunday Tribune, The Sunday Business Post, Ireland on Sunday and the Sunday World.

In Northern Ireland the three main daily newspapers are The News Letter, which is Unionist in outlook, The Irish News, mainly Nationalist in outlook and the Belfast Telegraph. Also widely available are the Northern Irish versions of the main UK wide daily newspapers and some Scottish dailies such as the Daily Record.

In terms of Sunday papers the Belfast Telegraph is the only one of the three main Northern Irish dailies that has a Sunday publication which is called the Sunday Life. Apart from this all the main UK wide Sunday papers such as The Sun on Sunday are widely available as are some Irish papers such as the Sunday world.

There are quite a large number of local weekly newspapers both North and South, with most counties and large towns having two or more newspapers. Curiously Dublin remains one of the few places in Ireland without a major local paper since the Dublin Evening Mail closed down in the 1960s. In 2004 the Dublin Daily was launched, but failed to attract enough readers to make it viable.

One major criticism of the Republic of Ireland newspaper market is the strong position Independent News & Media has on the market. It controls the Evening Herald, Irish Independent, Sunday Independent, Sunday World and The Star as well as holding a large stake in the cable company Chorus, and indirectly controlling The Sunday Tribune. The Independent titles are perceived by many Irish republicans as having a pro-British stance. In parallel to this, the Independent titles are perceived by many opposition supporters as being pro Fianna Fáil[citation needed].

The Irish magazine market is one of the world's most competitive, with hundreds of international magazines available in Ireland, ranging from Time and The Economist to Hello! and Reader's Digest. This means that domestic titles find it very hard to retain readership. Among the best-selling Irish magazines are the RTÉ Guide, Ireland's Eye, Irish Tatler, VIP, Phoenix and In Dublin.

Radio

editThe first known radio transmission in Ireland was a call to arms made from the General Post Office in O'Connell Street during the Easter Rising. The first official radio station on the island was 2BE Belfast, which began broadcasting in 1924. This was followed in 1926 by 2RN Dublin and 6CK Cork in 1927. 2BE Belfast later became BBC Radio Ulster and 2RN Dublin became RTÉ. The first commercial radio station in the Republic, Century Radio, came on air in 1989.

During the 1990s and particularly the early 2000s, dozens of local radio stations have gained licences. This has resulted in a fragmentation of the radio broadcast market. This trend is most noticeable in Dublin where there are now 6 private licensed stations in operation.

Television

editDifferent television stations are available depending on location in Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland. In Northern Ireland the main terrestrial television stations are the main UK wide channels BBC One, BBC Two, ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5. Both the BBC and ITV have local regional programing specific to Northern Ireland produced and broadcast through BBC Northern Ireland and UTV.

In terms of Satellite-carried channels in Northern Ireland these are the same as for the rest of the United Kingdom including all Sky channels.

In the Republic of Ireland some areas first received signal from BBC Wales and then latter from BBC Northern Ireland when it began broadcasting television programmes in 1959 before RTÉ Television opened in 1961. Today the Republic's main terrestrial channels are RTÉ One, RTÉ Two, TV3 which began broadcasting in 1998 and Teilifís na Gaeilge (TnaG), now called TG4 which started its Irish language service in 1996.

British and satellite-carried international television channels have widespread audiences in the Republic. The BBC and ITV families of channels are available free to air across the Republic and there is widespread availability of the four main UK channels (BBC1, BBC2, ITV1 and Channel Four) but only limited coverage from Five. Sky One, E4, and several hundred satellite channels are widely available. Parts of the Republic can access the UK digital TV system Freeview.

Film

editThe Republic of Ireland's film industry has grown rapidly in recent years thanks largely to the promotion of the sector by Bord Scannán na hÉireann (The Irish Film Board)[69] and the introduction of generous tax breaks. Some of the most successful Irish films included Intermission (2001), Man About Dog (2004), Michael Collins (1996), Angela's Ashes (1999), My Left Foot (1989), The Crying Game (1992), In the Name of the Father (1994) and The Commitments (1991). The most successful Irish film directors are Kenneth Branagh, Martin McDonagh, Neil Jordan, John Carney, and Jim Sheridan. Irish actors include Richard Harris, Peter O'Toole, Maureen O'Hara, Brenda Fricker, Michael Gambon, Colm Meaney, Gabriel Byrne, Pierce Brosnan, Liam Neeson, Daniel Day-Lewis, Ciarán Hinds, James Nesbitt, Cillian Murphy, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Saoirse Ronan, Brendan Gleeson, Domhnall Gleeson, Michael Fassbender, Ruth Negga, Jamie Dornan and Colin Farrell.

Ireland has also proved a popular location for shooting films with The Quiet Man (1952), Saving Private Ryan (1998), Braveheart (1995), King Arthur (2004) and P.S. I Love You (2007) all being shot in Ireland.

Cultural institutions, organisations and events

editIreland is well supplied with museums and art galleries and offers, especially during the summer months, a wide range of cultural events. These range from arts festivals to farming events. The most popular of these are the annual Dublin Saint Patrick's Day Festival which attracts on average 500,000 people and the National Ploughing Championships with an attendance in the region of 400,000. There are also a number of Summer Schools on topics from traditional music to literature and the arts.

Major organisations responsible for funding and promoting Irish culture are:

- Arts Council of Ireland

- Arts Council of Northern Ireland

- Culture Ireland

- Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media (Republic of Ireland)

- Department for Communities (Northern Ireland)

- Foras na Gaeilge

- List of institutions and organisations

- Abbey Theatre

- Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge

- Ambassador Theatre

- Aosdána

- Arts Council of Ireland

- Art Projects Network

- Chester Beatty Library

- Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann

- Conradh na Gaeilge

- Cork Opera House

- Crawford Art Gallery

- Culture Ireland

- Druid Theatre, Galway

- Dublin Writers Museum

- Gael Linn

- Gaelchultúr

- Gaelic Athletic Association

- Gate Theatre

- Glór na nGael

- Grand Opera House, Belfast

- Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery, Dublin

- Heritage Council

- Irish Architecture Foundation

- Irish Georgian Society

- Ireland Literature Exchange (ILE)

- Irish Museum of Modern Art at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham

- Irish Museums Association

- James Joyce Centre

- Lime Tree Theatre, Limerick

- Macnas, performance arts company, Galway

- National Archives of Ireland

- National Concert Hall

- National Folklore Collection UCD

- National Gallery of Ireland

- National Library of Ireland

- National Museums Northern Ireland

- National Museum of Ireland

- National Photographic Archive

- National Transport Museum of Ireland

- National Wax Museum

- Northern Ireland Screen

- National Trust (UK)

- Office of Public Works

- Poetry Ireland

- Royal Dublin Society (RDS)

- Royal Irish Academy

- Royal Irish Academy of Music

- Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland

- Royal Ulster Academy of Arts

- SFX City Theatre

- Taibhdhearc na Gaillimhe, Irish language theatre, Galway

- Temple Bar Cultural Trust

- The Helix, performing arts centre, Dublin

- The Hunt Museum, Limerick

- The Point Theatre

- Ulster American Folk Park, Omagh

- Ulster Folk and Transport Museum, County Down

- Ulster Museum, Belfast

- University Concert Hall, Limerick

- Events

- All-Ireland Senior Football Championship

- All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship

- Bealtaine

- Bloomsday

- Bray Jazz Festival

- Kilkenny Cat Laughs Comedy Festival

- City of Derry Jazz and Big Band Festival

- Clifden Arts Festival[70]

- Cork Jazz Festival

- Culture Night[71]

- Dublin Theatre Festival

- Earagail Arts Festival

- Féile na Gealaí[72]

- Fleadh Cheoil

- Galway Arts Festival

- Imbolg

- Liú Lúnasa[73]

- Lúnasa

- National Ploughing Championships

- Oireachtas na Gaeilge

- Pan Celtic Festival

- Puck Fair, Killorglin

- Saint Patrick's Day

- Samhain

- Seachtain na Gaeilge

- St. Patrick's Festival and Skyfest

- Swell Music and Arts Festival[74]

- The Twelfth

- Maiden City Festival

- Harvest Time Blues

- Heritage Week

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Margaret Scanlan (2006). "Culture and Customs of Ireland". p. 163. Greenwood Publishing Group

- ^ Weakliam, Peter (22 August 2024). "Dia dhuit: what's behind Irish language's religious roots?". RTE. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "Ireland & Spain". History Ireland. 2001. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ McCormack, Mike (2020). "The Irish-Spanish Connection". The Ancient Order of Hibernians. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ Hurley, Fiona Honor (2023). "THE IRISH / SPANISH CONNECTION...LETTER FROM CELTIBERIA". 24/7 Valencia. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Howell, Samantha (2016). "From Oppression to Nationalism: The Irish Penal Laws of 1695" (PDF). University of Hawai‘i at Hilo. p. 21.

- ^ Howe, Stephen (2000). Ireland and Empire: Colonial Legacies in Irish History and Culture. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–6.

- ^ White, Timothy J. (30 June 2010). "The Impact of British Colonialism on Irish Catholicism and National Identity: Repression, Reemergence, and Divergence". Études irlandaises (35–1): 21–37. doi:10.4000/etudesirlandaises.1743. ISSN 0183-973X.

- ^ "The Viking Age in Ireland". National Museum of Ireland. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ O'Malley, Aidan; Patten, Eve (2013). Ireland, West to East: Irish Cultural Connections with Central and Eastern Europe. Peter Lang Ltd, International Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-3034309134.

- ^ "Christian Census of Population 2016 – Profile 8 Irish Travellers, Ethnicity and Religion". Central Statistics Office. 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

Orthodox Christians have been the fastest growing religion in Ireland since 1991.

- ^ "Irish Census (2022) | Measuring religious adherence in Ireland". Faith Survey. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

The fastest growing branch of Christianity is the Orthodox Church, whose adherents in Ireland grew from 62,187 in 2016 to 105,827 in 2022.

- ^ "The origin of Halloween lies in Celtic Ireland" Archived 8 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Irish genealogy

- ^ King, Jeffrey (2019). "Lebor Gabála Erenn". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ Driscoll, K. The Early Prehistory in the West of Ireland: Investigations into the Social Archaeology of the Mesolithic, West of the Shannon, Ireland. (2006)

- ^ "Irish Travellers | People, Traditions, & Language | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 4 February 2024. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ Bohn Gmelch, Sharon; Gmelch, George (2014). "Nomads No More". National History Magazine.

- ^ Sir James G. Frazer – "The Golden Bough", 1922 – ISBN 1-85326-310-9

- ^ "Orangemen take part in Twelfth of July parades". BBC News. 12 July 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

Some marches have been a source of tension between nationalists who see the parades as triumphalist and intimidating, and Orangemen who believe it is their right to walk on public roads.

- ^ "Protestant fraternity returns to spiritual home". Reuters. 30 May 2009. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

The Orange Order's parades, with their distinctive soundtrack of thunderous drums and pipes, are seen by many Catholics in Northern Ireland as a triumphalist display.

- ^ "Ormeau Road frustration". An Phoblacht. 27 April 2000. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

The overwhelming majority of nationalists view Orange parades as triumphalist coat trailing exercises.

- ^ "Kinder, gentler or same old Orange?". Irish Central. 23 July 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

The annual Orange marches have passed relatively peacefully in Northern Ireland this year, and it seems a good faith effort is underway to try and reorient the day from one of triumphalism to one of community outreach and a potential tourist attraction ... The 12th may well have been a celebration of a long ago battle at the Boyne in 1690, but it came to symbolize for generations of Catholics the "croppie lie down" mentality on the Orange side. The thunderous beat of the huge drums was just a small way of instilling fear into the Nationalist communities, while the insistence on marching wherever they liked through Nationalist neighborhoods was also a statement of supremacy and contempt for the feelings of the other community.

- ^ Roe, Paul (2005). Ethnic violence and the societal security dilemma. Routledge. p. 62.

Ignatieff explains how the victory of William of Orange over Catholic King James 'became a founding myth of ethnic superiority...The Ulstermen's reward, as they saw it, was permanent ascendancy over the Catholic Irish'. Thus, Orange Order marches have come to symbolise the supremacy of Protestantism over Catholicism in Northern Ireland.

- ^ Wilson, Ron (1976). "Is it a religious war?". A flower grows in Ireland. University Press of Mississippi. p. 127.

At the close of the eighteenth century, Protestants, again feeling the threat of the Catholic majority, began forming secret societies which coalesced into the Orange Order. Its main purpose has always been to maintain Protestant supremacy

- ^ Knell, Bill (2018). Everything Irish About Ireland. p. 169.

- ^ Nicholson, Monique (1997). "From Pre-Christian Goddesses of Light". Canadian Woman Studies. 17: 14–17.

- ^ Rogers, Jonathan (2010). Saint Patrick. Thomas Nelson. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-59555-305-8. "By 431, there were enough believers in Ireland that Pope Celestine gave them their own bishop (Palladius)"

- ^ Von Dehsen, Christian D. (1999). Philosophers and Religious Leaders. Greenwood Publishing. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-57356-152-5.

- ^ Rogers, Nicholas (2002). "Samhain and the Celtic Origins of Halloween". Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, pp. 11–21. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516896-8.

- ^ "Religion - CSO - Central Statistics Office". www.cso.ie. 26 October 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Census 2021 main statistics religion tables". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. 7 September 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ "Religion - Other Christian - CSO - Central Statistics Office". www.cso.ie. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "Signs of hope and renewal amid the dramatic decline of the Catholic Church in Ireland". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "The faith of Ireland's Catholics continues, despite all". The Irish Times. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ "The Leprechaun Legend". Fantasy-ireland.com. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Arnold, Bettina (31 October 2001), "Bettina Arnold – Halloween Lecture: Halloween Customs in the Celtic World", Halloween Inaugural Celebration, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee: Center for Celtic Studies, archived from the original on 27 October 2007, retrieved 16 October 2007

- ^ Simpson, John; Weiner, Edmund (1989), Oxford English Dictionary (second ed.), London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8, OCLC 17648714

- ^ O'Driscoll, Robert (ed.) (1981) The Celtic Consciousness New York, Braziller ISBN 0-8076-1136-0 pp.197–216: Ross, Anne "Material Culture, Myth and Folk Memory" (on modern survivals); pp.217–242: Danaher, Kevin "Irish Folk Tradition and the Celtic Calendar" (on specific customs and rituals)

- ^ a b Frank Leslie's popular monthly: Volume 40 (1895) p.540

- ^ Rogers, Nicholas. (2002) "Festive Rights:Halloween in the British Isles". Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. p.48. Oxford University Press

- ^ Samhain, BBC Religion and Ethics. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ^ Council faces €1m clean-up bill after Halloween horror Irish Independent Retrieved 4 December 2010

- ^ Rogers, Nicholas. (2002). "Coming Over: Halloween in North America" Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. pp.49–77. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Dublin Travel Guide – Dublin Travel Guide Ireland". Onlinedublinguide.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Constitution of Ireland Archived 5 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Article 8

- ^ Hiberno-English Archive Archived 16 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Dho.ie

- ^ "Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act 2022". legislation.gov.uk. 2023.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Irish is third most used language in the country – 2011 Census". RTÉ News. 29 March 2012.

- ^ T., Lucas, A. (1989). Cattle in ancient Ireland. Kilkenny, Ireland: Boethius Press. ISBN 978-0-86314-145-4. OCLC 18623799.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ross, David (2002), Ireland: History of a Nation, New Lanark: Geddes & Grosset, p. 226, ISBN 978-1-84205-164-1

- ^ Lynch-Brennan, Margaret (2009). The Irish Bridget: Irish Immigrant Women in Domestic Service in America, 1840–1930.

- ^ "Countries Compared by Health > Heart disease deaths. International Statistics at NationMaster.com". Nationmaster.com. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Death to boring Saturday nights". The Irish Times. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ "The History of Belfast Underground Clubs 2". www.belfastundergroundclubs.com. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Snowdon, Christopher (2009). Velvet glove, iron fist: a history of anti-smoking. Little Dice. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-9562265-0-1.

- ^ "NI Smoking ban set for 2007". Flagship E-Commerce. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ "360 Link". doi:10.3109/09687637.2010.485590. S2CID 72967485.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (November 2009). "OECD Health Data 2009: Frequently Requested Data". Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "Alcohol Consumption in Ireland 2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

one to two standard drinks per drinking occasion, which is less than the 30% of drinkers in the 2007 SLÁN survey. One to two standard drinks amounts to 10–20 g of pure alcohol (and equates with one-half or one pint of beer, one to two pub measures of spirits, or 100 to 200 ml of wine) ... six or more standard drinks (which equates with 60 g of alcohol or more, for example, three or more pints of beer, six or more pub measures of spirits, or 600 ml or more of wine) on a typical drinking occasion. This equates with the criteria for risky single-occasion drinking or binge drinking.

- ^ "The Social Significance of Sport" (PDF). The Economic and Social Research Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ^ Henry, Mark (2021). In Fact An Optimist's Guide to Ireland at 100. Dublin: Gill Books. pp. 221–225. ISBN 978-0-7171-9039-3. OCLC 1276861968.

- ^ "Finfacts: Irish business, finance news on economics". Finfacts.com. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Sports Participation and Health Among Adults in Ireland" (PDF). The Economic and Social Research Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ^ "Italia 90: 'I missed it... I was in Italy". The Irish Independent

- ^ Keane, Trevor (1 October 2010). Gaffers: 50 Years of Irish Football Managers. Mercier Press Ltd. p. 211.

- ^ "Why are the same fans not celebrating both Irish victories?". The Irish Times.

- ^ "Welcome to the Irish Film Board". Archived from the original on 16 March 2005. Retrieved 20 March 2005.

- ^ "The 36th Clifden Arts Festival 2013, September 19-29: Clifden, Connemara, County Galway | Celebrating 36 Years of bringing the Arts to Clifden". Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ "Culture Night". Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "GAILEARAÍ: Na Gaeil imithe le 'Gealaí' ag féile cheoil i Ráth Chairn!". Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "Tús á chur le féile Liú Lúnasa i mBéal Feirste anocht". Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "Scoth an cheoil ag SWELL ar Oileán Árainn Mhór, Co. Dhún na nGall". Retrieved 8 September 2018.

External links

edit- BBC Northern Ireland Television & Radio Archive

- Central Statistics Office Ireland

- Irish Department of Foreign Affairs: Facts about Ireland

- Irish Broadcasting

- Population figures by religion

- Pobal Eolas Ilmheáin Gaeilge – PEIG.ie

- Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge provides a diploma course in indigenous Irish culture