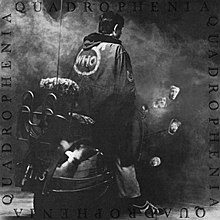

Quadrophenia is the sixth studio album by the English rock band the Who, released as a double album on 26 October 1973[4] by Track Records. It is the group's third rock opera, the previous two being the "mini-opera" song "A Quick One, While He's Away" (1966) and the album Tommy (1969). Set in London and Brighton in 1965, the story follows a young mod named Jimmy and his search for self-worth and importance. Quadrophenia is the only Who album entirely written by Pete Townshend.

| Quadrophenia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 26 October 1973 | |||

| Recorded |

| |||

| Studio | Olympic, Ramport and Ronnie Lane's Mobile Studio, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 81:42 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | The Who | |||

| The Who chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Quadrophenia | ||||

| ||||

The group started work on the album in 1972 in an attempt to follow up Tommy and Who's Next (1971), both of which had achieved substantial critical and commercial success. Recording was delayed while bassist John Entwistle and singer Roger Daltrey recorded solo albums and drummer Keith Moon worked on films. Because a new studio was not finished in time, the group had to use Ronnie Lane's Mobile Studio. The album makes significant use of Townshend's multi-track synthesizers and sound effects, as well as Entwistle's layered horn parts. Relationships between the group and manager Kit Lambert broke down irretrievably during recording and Lambert had left the band's service by the time the album was released.

Quadrophenia was released to a positive reception in both the UK and the US, but the resulting tour was marred with problems with backing tapes replacing the additional instruments on the album, and the stage piece was retired in early 1974. It was revived in 1996 with a larger ensemble, and a further tour took place in 2012. The album made a positive impact on the mod revival movement of the late 1970s, and the resulting 1979 film adaptation was successful. The album has been reissued on compact disc several times, and seen several remixes that corrected some perceived flaws in the original release.

Plot

editThe original release of Quadrophenia came with a set of recording notes for reviewers and journalists that explained the basic story and plot.[5]

The narrative centres on a young working-class mod named Jimmy. He likes drugs, beach fights and romance,[6] [7] and becomes a fan of the Who after a concert in Brighton,[8] but is disillusioned by his parents' attitude towards him, dead-end jobs and an unsuccessful trip to see a psychiatrist.[6] He clashes with his parents over his use of amphetamines,[8] and has difficulty finding regular work and doubts his own self-worth,[9] quitting a job as a dustman after only two days.[8] Though he is happy to be "one" of the mods, he struggles to keep up with his peers, and his girlfriend leaves him for his best friend.[6]

After destroying his scooter and contemplating suicide, he decides to take a train to Brighton, where he had enjoyed earlier experiences with fellow mods. However, he discovers the "Ace Face" who led the gang now has a menial job as a bellboy in a hotel.[6] He feels everything in his life has rejected him, steals a boat, and uses it to sail out to a rock overlooking the sea.[8] On the rock and stuck in the rain, he contemplates his life. The ending is left ambiguous as to what happens to Jimmy.[6]

Background

edit1972 was the least active year for the Who since they had formed. The group had achieved great commercial and critical success with the albums Tommy and Who's Next, but were struggling to come up with a suitable follow-up.[10] The group recorded new material with Who's Next collaborator Glyn Johns in May 1972, including "Is It in My Head" and "Love Reign O'er Me" which were eventually released on Quadrophenia, and a mini-opera called "Long Live Rock – Rock Is Dead", but the material was considered too derivative of Who's Next and sessions were abandoned.[11] In an interview for Melody Maker, guitarist and bandleader Pete Townshend said "I've got to get a new act together… People don't really want to sit and listen to all our past".[12] He had become frustrated that the group had been unable to produce a film of Tommy (a film version of Tommy would be released in 1975) or Lifehouse (the abortive project that resulted in Who's Next), and decided to follow Frank Zappa's idea of producing a musical soundtrack that could produce a narrative in the same way as a film. Unlike Tommy, the new work had to be grounded in reality and tell a story of youth and adolescence that the audience could relate to.[13]

Townshend became inspired by "Long Live Rock – Rock Is Dead"'s theme and in autumn 1972 began writing material, while the group put out unreleased recordings including "Join Together" and "Relay" to keep themselves in the public eye. In the meantime, bassist John Entwistle released his second solo album, Whistle Rymes, singer Roger Daltrey worked on solo material, and Keith Moon featured as a drummer in the film That'll Be the Day.[14] Townshend had met up with "Irish" Jack Lyons, one of the original Who fans, which gave him the idea of writing a piece that would look back on the group's history and its audience.[15] He created the character of Jimmy from an amalgamation of six early fans of the group, including Lyons, and gave the character a four-way split personality, which led to the album's title (a play on schizophrenia).[6] Unlike other Who albums, Townshend insisted on composing the entire work, though he deliberately made the initial demos sparse and incomplete so that the other group members could contribute to the finished arrangement.[16]

Work was interrupted for most of 1972 in order to work on Lou Reizner's orchestral version of Tommy.[17] Daltrey finished his first solo album, which included the hit single "Giving It All Away",[18] fueling rumours of a split in the press. Things were not helped by Daltrey discovering that managers Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp had large sums of money unaccounted for, and suggested they should be fired, which Townshend resisted.[19]

Recording

editIn order to do justice to the recording of Quadrophenia, the group decided to build their own studio, Ramport Studios in Battersea. Work started on building Ramport in November 1972, but five months later it still lacked an adequate mixing desk that could handle recording Quadrophenia.[20] Instead, Townshend's friend Ronnie Lane, bassist for Faces, loaned his mobile studio for the sessions.[21] Lambert ostensibly began producing the album in May,[22] but missed recording sessions and generally lacked discipline. By mid-1973, Daltrey demanded that Lambert leave the Who's services.[23] The band recruited engineer Ron Nevison, who had worked with Townshend's associate John Alcock, to assist with engineering.[24]

To illustrate the four-way split personality of Jimmy, Townshend wrote four themes, reflecting the four members of the Who. These were "Bell Boy" (Moon), "Is It Me?" (Entwistle), "Helpless Dancer" (Daltrey) and "Love Reign O'er Me" (Townshend).[25] Two lengthy instrumentals on the album, the title track and "The Rock", contain the four themes, separately and together. The instrumentals were not demoed but built up in the studio.[26] Who author John Atkins described the instrumental tracks as "the most ambitious and intricate music the group ever undertook."[25]

Most tracks involved each of the group recording their parts separately;[22] unlike earlier albums, Townshend had left space in his demos for other band members to contribute, though most of the synthesizers on the finished album came from his ARP 2500 synthesizer and were recorded at home.[24][16] The only song arranged by the band in the studio was "5:15".[26] According to Nevison, the ARP 2500 was impossible to record in the studio, and changing sounds was cumbersome due to a lack of patches, which required Townshend to work on these parts at home, working late into the night.[24] To obtain a good string section sound on the album, Townshend bought a cello and over two weeks learned how to play it well enough to be recorded.[27]

Entwistle recorded his bass part to "The Real Me" in one take on a Gibson Thunderbird[28] and spent several weeks during the summer arranging and recording numerous multi-tracked horn parts.[29] Having been forced to play more straightforwardly by Johns on Who's Next, Moon returned to his established drumming style on Quadrophenia. He contributed lead vocals to "Bell Boy", where he deliberately showcased an exaggerated narrative style.[30] For the finale of "Love, Reign O'er Me", Townshend and Nevison set up a large group of percussion instruments, which Moon played before kicking over a set of tubular bells, which can be heard on the final mix.[29]

During the album production, Townshend made many field recordings with a portable reel-to-reel recorder. These included waves washing on a Cornish beach and the doppler whistle of a diesel train recorded near Townshend's house at Goring-on-Thames.[6] The ending of "The Dirty Jobs" includes a musical excerpt from The Thunderer, a march by John Philip Sousa, which Nevison recorded while watching a brass band play in Regent's Park.[24] Assembling the field recordings in the studio was problematic; at one point, during "I Am the Sea", nine tape machines were running sound effects.[29] According to Nevison, Townshend produced the album single-handedly, adding that "everything started when Pete got there, and everything finished when Pete left".[24] Townshend began mixing the album in August at his home studio in Goring along with Nevison.[31]

Release

editThe album was preceded by the single "5:15" in the UK, which benefited from a live appearance on Top of the Pops on 4 October 1973 and was released the next day.[32] It reached No. 20 in the charts.[33] In the US, "Love Reign O'er Me" was chosen as the lead single. [32]

Quadrophenia was originally released in North America on 26 October and in the UK on 29 October,[34] but fans found it difficult to find a copy due to a shortage of vinyl caused by the OPEC oil embargo.[4] In the UK, Quadrophenia reached No. 2, being held off the top spot by David Bowie's Pin Ups.[a] The album reached No. 2 on the US Billboard chart, the highest position of any Who album in that country, being kept from No. 1 by Elton John's Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.[35]

The album was originally released as a two-LP set with a gatefold jacket and a booklet containing lyrics, a text version of the story, and photographs taken by Ethan Russell illustrating it.[36] MCA Records re-released the album as a two-CD set in 1985 with the lyrics and text storyline on a thin fold-up sheet but none of the photographs.[37] The album was reissued as a remastered CD in 1996, featuring a reproduction of the original album artwork.[38] The original mix had been criticised in particular for Daltrey's vocals being buried, so the 1996 CD was completely remixed by Jon Astley and Andy Macpherson.[39]

In 2011, Townshend and longtime Who engineer Bob Pridden remixed the album, resulting in a deluxe five-disc box set.[40] Unlike earlier reissues, this set contains two discs of demos, including some songs that were dropped from the final running order of the album, and a selection of songs in 5.1 surround sound. The box set came with a 100-page book including an essay by Townshend about the album sessions, with photos.[41] At the same time, the standard two-CD version was re-released with a selection of the demos as bonus content; some Disc Two tracks were moved to Disc One to accommodate space for these demos. In 2014, the album was released on Blu-ray Audio featuring a brand-new remix of the entire album by Townshend and Pridden in 5.1 surround sound as well the 2011 Deluxe Edition stereo remix and the original 1973 stereo LP mix.[42]

Reception

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [43] |

| Christgau's Record Guide | A−[44] |

| Clash | 10/10[45] |

| Digital Spy | [46] |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [47] |

| MusicHound Rock | 4/5[48] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [49] |

| Tom Hull – on the Web | B[50] |

Critical reaction to Quadrophenia was positive. Melody Maker's Chris Welch wrote "rarely have a group succeeded in distilling their essence and embracing a motif as convincingly", while Charles Shaar Murray described the album in New Musical Express as the "most rewarding musical experience of the year".[51] Reaction in the US was generally positive, though Dave Marsh, writing in Creem gave a more critical response.[51] Lenny Kaye, wrote in Rolling Stone that "the Who as a whole have never sounded better" but added, "on its own terms, Quadrophenia falls short of the mark".[52] In a year-end top albums list for Newsday, Robert Christgau ranked it seventh, and found it exemplary of how 1973's best records "fail to reward casual attention. They demand concentration, just like museum and textbook art."[53]

Retrospective reviews were also positive. Writing in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981), Christgau regarded Quadrophenia as more of an opera than Tommy, possessing a brilliantly written albeit confusing plot, jarring but melodic music, and compassionate lyrics about "Everykid as heroic fuckup, smart enough to have a good idea of what's being done to him and so sensitive he gets pushed right out to the edge anyway".[44] Chris Jones, writing for BBC Music, said "everything great about the Who is contained herein."[54] In 2013, Billboard, reviewing the album for its 40th anniversary, said: "Filled with performances packed with life and depth and personality, Quadrophenia is 90 minutes of the Who at its very best."[55] The album has sold 1 million copies and has been certified Platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America.[56] In 2000 Q magazine placed Quadrophenia at No. 56 in its list of the 100 Greatest British Albums Ever.[57] The album has been ranked at No. 267 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[58] It is also ranked at No. 86 on VH1's list of the 100 greatest albums of all time.[59]

Townshend now considers Quadrophenia to be the last great album that the Who recorded. In 2011, he said the group "never recorded anything that was so ambitious or audacious again", and implied that it was the last album to feature good playing by Keith Moon.[60]

Live performances

edit1973–1974 tour

editThe band toured in support of Quadrophenia but immediately encountered difficulties playing the material live. To achieve the rich overdubbed sound of the album on stage, Townshend wanted Chris Stainton (who had played piano on some tracks) to join as a touring member. Daltrey objected to this and believed the Who's performances should only have the four core members.[61] To obtain the required instrumentation without additional musicians, the group elected to employ taped backing tracks for live performance, as they had already done for "Baba O'Riley" and "Won't Get Fooled Again".[62] Initial performances were plagued by malfunctioning equipment. Once the tapes started, the band had to play to them, which constrained their styles. Moon, in particular, found playing Quadrophenia difficult as he was forced to stick to a click track instead of watching the rest of the band.[63][64] The group only allowed two days of rehearsals with the tapes before touring, one of which was abandoned after Daltrey punched Townshend following an argument.[63]

The tour started on 28 October 1973. The original plan had been to play most of the album, but after the first gig at Stoke-on-Trent, the band dropped "The Dirty Jobs", "Is It in My Head" and "I've Had Enough" from the set.[4] Both Daltrey and Townshend felt they had to describe the plot in detail to the audience, which took up valuable time on stage.[65] A few shows later in Newcastle upon Tyne, the backing tapes to "5:15" came in late. Townshend stopped the show, grabbed Pridden, who was controlling the mixing desk, and dragged him onstage, shouting obscenities at him. Townshend subsequently picked up some of the tapes and threw them over the stage, kicked his amplifier over, and walked off. The band returned 20 minutes later, playing older material.[66][67] Townshend and Moon appeared on local television the following day and attempted to brush things off. The Who played two other shows in Newcastle without incident.[66]

The US tour started on 20 November at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. The group were nervous about playing Quadrophenia after the British tour, especially Moon. Before the show, he was offered some tranquillisers from a fan. Just after the show started, the fan collapsed and was hospitalised. Moon's playing, meanwhile, became incredibly erratic, particularly during Quadrophenia where he did not seem to be able to keep time with the backing tapes. Towards the end of the show, during "Won't Get Fooled Again", he passed out over his drumkit. After a 20-minute wait, Moon reappeared onstage, but after a few bars of "Magic Bus", collapsed again, and was immediately taken to hospital.[68] Scot Halpin, an audience member, convinced promoter Bill Graham to let him play drums, and the group closed the show with him. Moon had a day to recover, and by the next show at the Los Angeles Forum, was playing at his usual strength.[69] The group began to get used to the backing tapes, and the remainder of gigs for the US tour were successful.[70]

The tour continued in February 1974, with a short series of gigs in France.[71] The final show at the Palais de Sports in Lyon on the 24th was the last time Quadrophenia was played as a stage piece with Moon, who died in 1978. Townshend later said that Daltrey "ended up hating Quadrophenia – probably because it had bitten back".[72] However, a small selection of songs remained in the set list; live performances of "Drowned" and "Bell Boy" filmed at Charlton Athletic football ground on 18 May were later released on the 30 Years of Maximum R&B box set.[73]

1996–1997 tour

editIn June 1996, Daltrey, Townshend and Entwistle revived Quadrophenia as a live concert. They performed at Hyde Park, London as part of the Prince's Trust "Masters of Music" benefit concert, playing most of the album for the first time since 1974. The concert was not billed as the Who, but credited to the three members individually. The performance also included Gary Glitter as the Godfather, Phil Daniels as the Narrator and Jimmy, Trevor MacDonald as the newsreader, Adrian Edmondson as the Bell Boy and Stephen Fry as the hotel manager. The musical lineup included Townshend's brother Simon, Zak Starkey on drums (his first appearance with the Who), guitarists David Gilmour (who played the bus driver) and Geoff Whitehorn, keyboardists John "Rabbit" Bundrick and Jon Carin, percussionist Jody Linscott, Billy Nicholls leading a two-man/two-woman backing vocal section, and five brass players. During rehearsals, Daltrey was struck in the face by Glitter's microphone stand, and performed the concert wearing an eyepatch.[74]

A subsequent tour of the US and UK followed, employing most of the same players but with Billy Idol replacing Edmondson,[75] Simon Townshend replacing Gilmour and P. J. Proby replacing Glitter during the second half of the tour. 85,000 fans saw the ensemble perform Quadrophenia at Madison Square Garden over six nights in July 1996.[76] A recording from the tour was subsequently released in 2005 as part of Tommy and Quadrophenia Live.[77]

2010s tours

editThe Who performed Quadrophenia at the Royal Albert Hall on 30 March 2010 as part of the Teenage Cancer Trust series of ten gigs. This one-off performance of the rock opera featured guest appearances from Pearl Jam's Eddie Vedder and Kasabian's Tom Meighan.[78]

In November 2012, the Who started a U.S. tour of Quadrophenia, dubbed "Quadrophenia and More". The group played the entire album without any guest singers or announcements with the then regular Who line-up (including Starkey and bassist Pino Palladino, who replaced Entwistle following his death in 2002) along with five additional musicians. The tour included additional video performances, including Moon singing "Bell Boy" from 1974 and Entwistle's bass solo in "5:15" from 2000.[79] After Starkey injured his wrist, session drummer Scott Devours replaced him for part of the tour with minimal rehearsal.[80][81][82] The tour progressed, with Devours drumming, to the UK in 2013, ending in a performance at Wembley Arena in July.[83]

In September 2017, Townshend embarked on a short tour with Billy Idol, Alfie Boe, and an orchestra entitled "Classic Quadrophenia".[84][85]

Adaptations

editFilm

editQuadrophenia was revived for a film version in 1979, directed by Franc Roddam. The film attempted to portray an accurate visual interpretation of Townshend's vision of Jimmy and his surroundings, and included Phil Daniels as Jimmy and Sting as the Ace Face.[86] Unlike the Tommy film, the music was largely relegated to the background, and was not performed by the cast as in a rock opera. The film soundtrack included three additional songs written by Townshend, which were Kenney Jones' first recordings as an official member of the Who.[87] The film was a commercial and critical success, as it conveniently coincided with the mod revival movement of the late 1970s.[88]

Other productions

editThere have been several amateur productions of a Quadrophenia musical. In 2007, the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama performed a musical based on the original album at the Sherman Theatre, Cardiff, featuring a cast of 12 backed by an 11-piece band.[89]

In October 1995, the rock group Phish, with an additional four-man horn section, performed Quadrophenia in its entirety as their second Halloween musical costume at the Rosemont Horizon in the Chicago suburb of Rosemont, Illinois.[90] The recording was later released as a part of Live Phish Volume 14.[91] The band also covered the tracks "Drowned" and "Sea and Sand" on their live album New Year's Eve 1995 – Live at Madison Square Garden.[92]

In June 2015, Townshend produced an orchestral version of the album entitled Classic Quadrophenia. The album was orchestrated by his partner Rachel Fuller and conducted by Robert Ziegler, with instrumentation provided by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. Tenor Alfie Boe sang the lead role, supported by the London Oriana Choir, Billy Idol, Phil Daniels, and Townshend.[93]

Track listing

editOriginal release

editAll tracks are written by Pete Townshend

| No. | Title | Lead vocal | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "I Am the Sea" | Roger Daltrey | 2:09 |

| 2. | "The Real Me" | Daltrey | 3:21 |

| 3. | "Quadrophenia" | (instrumental) | 6:14 |

| 4. | "Cut My Hair" | Pete Townshend (verses), Daltrey (chorus) | 3:45 |

| 5. | "The Punk and the Godfather" | Daltrey (verses and chorus), Townshend (bridge) | 5:11 |

| Total length: | 20:40 | ||

- Track 5 is titled "The Punk Meets the Godfather" on the American version

| No. | Title | Lead vocal | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "I'm One" (At least) | Townshend | 2:38 |

| 2. | "The Dirty Jobs" | Daltrey | 4:30 |

| 3. | "Helpless Dancer" (Roger's theme) | Daltrey | 2:34 |

| 4. | "Is It in My Head?" | Daltrey (verses, bridge), John Entwistle (chorus) | 3:44 |

| 5. | "I've Had Enough" | Daltrey and Townshend | 6:15 |

| Total length: | 19:41 | ||

- Track 3 includes the intro to "The Kids Are Alright" from My Generation

| No. | Title | Lead vocal | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "5:15" | Daltrey, Townshend (intro and coda) | 5:01 |

| 2. | "Sea and Sand" | Daltrey and Townshend | 5:02 |

| 3. | "Drowned" | Daltrey | 5:28 |

| 4. | "Bell Boy" (Keith's theme) | Daltrey and Keith Moon | 4:56 |

| Total length: | 20:27 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocal | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Doctor Jimmy" (Including John's theme, "Is It Me?”) | Daltrey | 8:37 |

| 2. | "The Rock" | (instrumental) | 6:38 |

| 3. | "Love, Reign o'er Me" (Pete's theme) | Daltrey | 5:49 |

| Total length: | 21:04 | ||

Quadrophenia: The Director's Cut track listing

edit| No. | Title | Recording date | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Real Me" | written and recorded in October 1972 | 4:24 |

| 2. | "Quadrophenia – Four Overtures" | in 1973 | 6:20 |

| 3. | "Cut My Hair" | written in June 1972 | 3:28 |

| 4. | "Fill No. 1 – Get Out and Stay Out" | 12 November 1972 | 1:22 |

| 5. | "Quadrophenic – Four Faces" | in July 1972 | 4:02 |

| 6. | "We Close Tonight" | in July 1972 | 2:41 |

| 7. | "You Came Back" | in July 1972 | 3:16 |

| 8. | "Get Inside" | written in April 1972 | 3:09 |

| 9. | "Joker James" | in July 1972 | 3:41 |

| 10. | "Ambition" | written early in 1972 | 0:00 |

| 11. | "Punk" | 18 November 1972 | 4:56 |

| 12. | "I'm One" | 15 November 1972 | 2:37 |

| 13. | "Dirty Jobs" | 25 July 1972 | 3:45 |

| 14. | "Helpless Dancer" | in 1973 | 2:16 |

| Total length: | 43:38 | ||

| No. | Title | Recording date | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Is It in My Head?" | 30 April 1972 | 4:12 |

| 2. | "Anymore" | listed as recorded on 10 November 1971, but probably a misprint; actual year would have been 1972 | 3:19 |

| 3. | "I've Had Enough" | written and recorded on 17 December 1972 | 6:21 |

| 4. | "Fill No. 2" | 12 November 1972 | 1:30 |

| 5. | "Wizardry" | in August 1972 | 3:10 |

| 6. | "Sea and Sand" | written and recorded on 1 November 1972 | 4:13 |

| 7. | "Drowned" | in March 1970 | 4:14 |

| 8. | "Is It Me?" | 20 March 1973 | 4:37 |

| 9. | "Bell Boy" | 3 March 1973 | 5:03 |

| 10. | "Doctor Jimmy" | 27 July 1972 | 7:28 |

| 11. | "Finale – The Rock" | between 25 March and 1 May 1973 | 7:57 |

| 12. | "Love Reign O'er Me" | 10 May 1972 | 5:10 |

| Total length: | 57:14 | ||

Personnel

editTaken from the sleeve notes:[94]

|

The Who

Additional musicians

|

Production

|

Charts

edit

Weekly chartsedit

|

Year-end chartsedit

|

Certifications

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[106] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| France (SNEP)[107] | Gold | 100,000* |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[108] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[109] | Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

edit- ^ Ironically, Pin Ups contained cover versions of the Who songs "I Can't Explain" and "Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere".

References

edit- ^ Barker, Emily (24 October 2013). "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time: 300-201". NME. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ Kemp, Mark (2004). "The Who". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 871–873. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Segretto, Mike (2022). "1973". 33 1/3 Revolutions Per Minute – A Critical Trip Through the Rock LP Era, 1955–1999. Backbeat. pp. 293–294. ISBN 9781493064601.

- ^ a b c Unterberger 2011, p. 232.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 420.

- ^ a b c d e f g Neill & Kent 2002, p. 317.

- ^ "Forty years ago pictures of Mods and Rockers shocked polite society". The Independent. 3 April 2004. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d Quadrophenia (1996 CD remaster) (Media notes). Polydor. pp. 2–4. 531 971-2.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 419.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 395.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 396.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2002, p. 315.

- ^ Atkins 2000, p. 177.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 396, 397.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 399.

- ^ a b Marsh 1983, p. 413.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 400.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 405.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 406.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 410.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2002, p. 324.

- ^ a b c Neill & Kent 2002, p. 329.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 412.

- ^ a b c d e "Interview with Ron Nevison by Richie Unterberger" (Interview). Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ a b Atkins 2000, p. 206.

- ^ a b Atkins 2000, p. 181.

- ^ Unterberger 2011, p. 186.

- ^ Unterberger 2011, p. 203.

- ^ a b c Marsh 1983, p. 414.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 345–346.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2002, p. 331.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2002, p. 334.

- ^ Atkins 2000, p. 192.

- ^ "BPI".

- ^ "The Who Official Band Website". Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ^ Gildart, Keith (2013). Images of England Through Popular Music: Class, Youth and Rock 'n' Roll, 1955–1976. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-137-38425-6.

- ^ "Quadrophenia – The Who – MCA #6895". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ "The Who – Quadrophenia – Polydor #5319712". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Atkins 2000, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Greene, Andy (2 June 2011). "Pete Townshend Announces 'Quadrophenia' Box Set". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Coplan, Chris (8 September 2011). "The Who details massive Quadrophenia: The Directors Cut box set". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Grow, Kory (17 April 2014). "The Who to Issue 'Quadrophenia: Live in London' Concert Film". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Quadrophenia – The Who | Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: W". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ "The Who – Quadrophenia: The Director's Cut | Reviews | Clash Magazine". Clashmusic.com. 19 March 2014. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ "The Who: 'Quadrophenia' (Deluxe Edition) – Album review – Music Review". Digital Spy. 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2007). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195313734.

- ^ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Visible Ink Press. p. 1227. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- ^ "The Who: Album Guide". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Hull, Tom (n.d.). "Grade List: The Who". Tom Hull – on the Web. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ a b Atkins 2000, p. 209.

- ^ Kaye, Lenny (20 December 1973). "The Who Quadrophenia Album Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (13 January 1974). "Returning With a Painful Top 30 List". Newsday. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ Jones, Chris (2008). "Review of The Who – Quadrophenia". BBC Music. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Rose, Caryn (19 October 2013). "The Who's Quadrophenia at 40: Classic Track-By-Track Review". Billboard. Archived from the original on 14 January 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Heritage Music & Entertainment Auction #7006. Heritage Capital Corporation. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-59967-369-1. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Clements, Ashley (29 January 2013). "Everything you need to know about The Who's Quadrophenia". GigWise. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "The Who, 'Quadrophenia' – 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "VH1 greatest albums of all time". VH1. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Graff, Gary (11 November 2011). "Pete Townshend on 'Quadrophenia,' The Who's 'Last Great Album'". Billboard. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Marsh 1983, pp. 425–426.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 247,359.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. 359.

- ^ Jackson, James (20 April 2009). "Pete Townshend on Quadrophenia, touring with The Who and the Mod revival". The Times. UK. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 360.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2002, p. 336.

- ^ Perrone, Pierre (24 January 2008). "The worst gigs of all time". Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 361.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 362.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 363.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 369.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2002, p. 346.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2002, pp. 351–352.

- ^ McMichael & Lyons 2011, pp. 820–821.

- ^ McMichael & Lyons 2011, p. 822.

- ^ McMichael & Lyons 2011, p. 823.

- ^ "Tommy and Quadrophenia: Live". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (31 March 2010). "The Who: Quadrophenia at the Royal Albert Hall, review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Greene, Andy (15 November 2012). "The Who Stage 'Quadrophenia' at Triumphant Brooklyn Concert". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Wolff, Sander (9 July 2013). "Scott Devours: From Here to the Who". Long Beach Post. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ Wolff, Sander (10 July 2013). "Scott Devours: From Here to the Who – Part 2". Long Beach Post. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ Wolff, Sander (12 July 2013). "Scott Devours: From Here to the Who – Part 3". Long Beach Post. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (24 June 2014). "The Who: Quadrophenia Live in London – The Sea and the Sand – exclusive footage". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ "Pete Townshend's Classic Quadrophenia With Billy Idol Announces U.S. Tour Dates (by Michael Gallucci)". ultimateclassicrock.com. 6 June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "Pete Townshend Plots Short 'Classic Quadrophenia' Tour – Townshend will revisit the Who's famous double album with an orchestra to reach "classical and pop music lovers alike" (by Elias Leight)". rollingstone.com. 6 June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 535.

- ^ Rayl, Salley; Henke, James (28 December 1978). "Kenny Jones Joins The Who". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ Marsh 1983, p. 510.

- ^ "Quadrophenia gets a Mod-ern staging". Wales Online. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ McKeough, Kevin (1 November 1995). "Phish Does The Who". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ "Live Phish, Vol. 14 – Phish". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ "Live at Madison Square Garden New Year's Eve 1995". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ "Pete Townshend announces classic Quadrophenia". The Who (official website). December 2014. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Quadrophenia (Media notes). Track Records. 1973. 2657 013.

- ^ Quadrophenia (CD reissue) (Media notes). Polydor. 1996. 531 971-2.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – The Who – Quadrophenia" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 4976a". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – The Who – Quadrophenia" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Classifiche". Musica e Dischi (in Italian). Retrieved 27 May 2022. Set "Tipo" on "Album". Then, in the "Artista" field, search "Who".

- ^ "The Who | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "The Who Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – The Who – Quadrophenia" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – The Who – Quadrophenia". Hung Medien. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. 1974. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "The Who / Roger Daltrey: A 'Platinum' Sales award for the album Quadrophenia". 18 March 2023.

- ^ "French album certifications – The Who" (in French). InfoDisc. Select THE WHO and click OK.

- ^ "British album certifications – The Who – Quadrophenia". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ "American album certifications – The Who – Quadrophenia". Recording Industry Association of America.

Sources

edit- Atkins, John (2000). The Who on Record: A Critical History, 1963–1998. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0609-8.

- Fletcher, Tony (1998). Dear Boy: The Life of Keith Moon. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84449-807-9.

- Marsh, Dave (1983). Before I Get Old: The Story of The Who. Plexus. ISBN 978-0-85965-083-0.

- McMichael, Joe; Lyons, Jack (2011). The Who: Concert File. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-737-2.

- Neill, Andrew; Kent, Matthew (2002). Anyway Anyhow Anywhere – The Complete Chronicle of The Who. Virgin. ISBN 978-0-7535-1217-3.

- Unterberger, Richie (2011). Won't Get Fooled Again: The Who from Lifehouse to Quadrophenia. Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-75-6.

Further reading

edit- Hughes, Rob (26 October 2016). "The Who: How We Made Quadrophenia". Classic Rock magazine. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

External links

edit- Quadrophenia at Discogs (list of releases)

- Liner Notes – Quadrophenia – fan site