Eflornithine, sold under the brand name Vaniqa among others, is a medication used to treat African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) and excessive hair growth on the face in women.[1][3][4] Specifically it is used for the second stage of sleeping sickness caused by T. b. gambiense and may be used with nifurtimox.[3][5] It is taken intravenously (injection into a vein) or topically.[3][4] It is an ornithine decarboxylase inhibitor.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Vaniqa, Iwilfin, others |

| Other names | α-difluoromethylornithine or DFMO |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | intravenous, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% (Intravenous) Negligible (topical) |

| Metabolism | Not metabolized |

| Elimination half-life | 8 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6H12F2N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 182.171 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects when applied as a cream include rash, redness, and burning.[4] Side effects of the injectable form include bone marrow suppression, vomiting, and seizures.[5] It is unclear if it is safe to use during pregnancy or breastfeeding.[5] It is recommended typically for children over the age of 12.[5]

Eflornithine was developed in the 1970s and came into medical use in 1990.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] In the United States the injectable form can be obtained from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[5] In regions of the world where the disease is common eflornithine is provided for free by the World Health Organization.[8]

Medical uses

editSleeping sickness

editSleeping sickness, or trypanosomiasis, is treated with pentamidine or suramin (depending on subspecies of parasite) delivered by intramuscular injection in the first phase of the disease, and with melarsoprol and eflornithine intravenous injection in the second phase of the disease. Efornithine is commonly given in combination with nifurtimox, which reduces the treatment time to 7 days of eflornithine infusions plus 10 days of oral nifurtimox tablets.[9]

Eflornithine is also effective in combination with other drugs, such as melarsoprol and nifurtimox. A study in 2005 compared the safety of eflornithine alone to melarsoprol and found eflornithine to be more effective and safe in treating second-stage sleeping sickness Trypanosoma brucei gambiense.[10] Eflornithine is not effective in the treatment of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense due to the parasite's low sensitivity to the drug. Instead, melarsoprol is used to treat Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense.[11] Another randomized control trial in Uganda compared the efficacy of various combinations of these drugs and found that the nifurtimox-eflornithine combination was the most promising first-line theory regimen.[12]

A randomized control trial was conducted in Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Uganda to determine if a 7-day intravenous regimen was as efficient as the standard 14-day regimen for new and relapsing cases. The results showed that the shortened regimen was efficacious in relapse cases, but was inferior to the standard regimen for new cases of the disease.[13]

Nifurtimox-eflornithine combination treatment (NECT) is an effective regimen for the treatment of second stage gambiense African trypanosomiasis.[14][15]

Trypanosome resistance

editAfter its introduction to the market in the 1980s, eflornithine has replaced melarsoprol as the first line medication against Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) due to its reduced toxicity to the host.[13] Trypanosoma brucei resistant to eflornithine was reported as early as the mid-1980s.[13]

The gene TbAAT6, conserved in the genome of Trypanosomes, is believed to be responsible for the transmembrane transporter that brings eflornithine into the cell.[16] The loss of this gene due to specific mutations causes resistance to eflornithine in several trypanosomes.[17] If eflornithine is prescribed to a patient with Human African trypanosomiasis caused by a trypanosome that contains a mutated or ineffective TbAAT6 gene, then the medication will be ineffective against the disease. Resistance to eflornithine has increased the use of melarsoprol despite its toxicity, which has been linked to the deaths of 5% of recipient HAT patients.[13]

Excess facial hair in women

editThe topical cream is indicated for treatment of facial hirsutism in women.[1][18] It is the only topical prescription treatment that slows the growth of facial hair.[19] In clinical studies with Vaniqa, 81% percent of women showed clinical improvement after twelve months of treatment.[20] Positive results were seen after eight weeks.[21] However, discontinuation of the cream caused regrowth of hair back to baseline levels within 8 weeks.[22]

Vaniqa treatment significantly reduces the psychological burden of facial hirsutism.[23]

Neuroblastoma

editIn the US, eflornithine is indicated to reduce the risk of relapse in people with high-risk neuroblastoma.[2]

Contraindications

editTopical

editTopical use is contraindicated in people hypersensitive to eflornithine or to any of the excipients.[24]

Throughout clinical trials, data from a limited number of exposed pregnancies indicate that there is no clinical evidence that treatment with Vaniqa adversely affects pregnant women or fetuses.[24]

Oral administration

editWhen taken orally the risk-benefit should be assessed in people with impaired renal function or pre-existing hematologic abnormalities, as well as those with eighth-cranial-nerve impairment.[25] Adequate and well-controlled studies with eflornithine have not been performed regarding pregnancy in humans. Eflornithine should only be used during pregnancy if the potential benefit outweighs the potential risk to the fetus. However, since African trypanosomiasis has a high mortality rate if left untreated, treatment with eflornithine may justify any potential risk to the fetus.[25]

Side effects

editEflornithine is not genotoxic; no tumour-inducing effects have been observed in carcinogenicity studies, including one photocarcinogenicity study.[26] No teratogenic effects have been detected.[27]

Topical

editThe topical form of elflornithine is sold under the brand name Vaniqa. The most frequently reported side effect is acne (7–14%). Other side effects commonly (> 1%) reported are skin problems, such as skin reactions from in-growing hair, hair loss, burning, stinging or tingling sensations, dry skin, itching, redness or rash.[28]

Intravenous

editThe intravenous dosage form of eflornithine is sold under the brand name Ornidyl. Most side effects related to systemic use through injection are transient and reversible by discontinuing the drug or decreasing the dose. Hematologic abnormalities occur frequently, ranging from 10 to 55%. These abnormalities are dose-related and are usually reversible. Thrombocytopenia is thought to be due to a production defect rather than to peripheral destruction. Seizures were seen in approximately 8% of patients, but may be related to the disease state rather than the drug. Reversible hearing loss has occurred in 30–70% of patients receiving long-term therapy (more than 4–8 weeks of therapy or a total dose of >300 grams); high-frequency hearing is lost first, followed by middle- and low-frequency hearing. Because treatment for African trypanosomiasis is short-term, patients are unlikely to experience hearing loss.[28]

Interactions

editTopical

editNo interaction studies with the topical form have been performed.[24]

Mechanism of action

editDescription

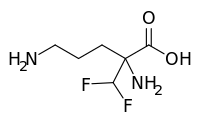

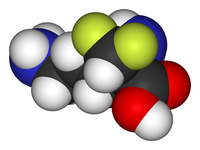

editEflornithine is a "suicide inhibitor," irreversibly binding to ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) and preventing the natural substrate ornithine from accessing the active site (Figure 1). Within the active site of ODC, eflornithine undergoes decarboxylation with the aid of cofactor pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP). Because of its additional difluoromethyl group in comparison to ornithine, eflornithine is able to bind to a neighboring Cys-360 residue, permanently remaining fixated within the active site.[27]

During the reaction, eflornithine's decarboxylation mechanism is analogous to that of ornithine in the active site, where transamination occurs with PLP followed by decarboxylation. During the event of decarboxylation, the fluoride atoms attached to the additional methyl group pull the resulting negative charge from the release of carbon dioxide, causing a fluoride ion to be released. In the natural substrate of ODC, the ring of PLP accepts the electrons that result from the release of CO2.[citation needed]

The remaining fluoride atom that resides attached to the additional methyl group creates an electrophilic carbon that is attacked by the nearby thiol group of Cys-360, allowing eflornithine to remain permanently attached to the enzyme following the release of the second fluoride atom and transimination.

Evidence

editThe reaction mechanism of Trypanosoma brucei's ODC with ornithine was characterized by UV-VIS spectroscopy in order to identify unique intermediates that occurred during the reaction. The specific method of multiwavelength stopped-flow spectroscopy utilized monochromatic light and fluorescence to identify five specific intermediates due to changes in absorbance measurements.[29] The steady-state turnover number, kcat, of ODC was calculated to be 0.5 s−1 at 4 °C.[29] From this characterization, the rate-limiting step was determined to be the release of the product putrescine from ODC's reaction with ornithine. In studying the hypothetical reaction mechanism for eflornithine, information collected from radioactive peptide and eflornithine mapping, high pressure liquid chromatography, and gas phase peptide sequencing suggested that Lys-69 and Cys-360 are covalently bound to eflornithine in T. brucei ODC's active site.[30] Utilizing fast-atom bombardment mass spectrometry (FAB-MS), the structural conformation of eflornithine following its interaction with ODC was determined to be (S)-((2-(1-pyrroline-methyl) cysteine, a cyclic imine adduct. Presence of this particular product was supported by the possibility to further reduce the end product to (S)-((2-pyrrole) methyl) cysteine in the presence of NaBH4 and oxidize the end product to (S)-((2-pyrrolidine) methyl) cysteine (Figure 2).[30]

Active site

editEflornithine's suicide inhibition of ODC physically blocks the natural substrate ornithine from accessing the active site of the enzyme (Figure 3).[27] There are two distinct active sites formed by the homodimerization of ornithine decarboxylase. The size of the opening to the active site is approximately 13.6 Å. When these openings to the active site are blocked, there are no other ways through which ornithine can enter the active site. During the intermediate stage of eflornithine with PLP, its position near Cys-360 allows an interaction to occur. As the phosphate of PLP is stabilized by Arg 277 and a Gly-rich loop (235-237), the difluoromethyl group of eflornithine is able to interact and remain fixated to both Cys-360 and PLP prior to transimination. As shown in the figure, the pyrroline ring interferes with ornithine's entry (Figure 4). Eflornithine will remain permanently bound in this position to Cys-360. As ODC has two active sites, two eflornithine molecules are required to completely inhibit ODC from ornithine decarboxylation.

-

Figure 1

(A) 3D structure of L-Ornithine (B) 3D structure of Eflornithine. This molecule is similar to the structure of L-Ornithine, but its alpha-difluoromethyl group allows interaction with Cys-360 in the active site -

Eflornithine ODC reaction mechanism

-

Figure 2

Experimental Evidence for Eflornithine End Product[30] -

Figure 3

Active Site of ODC Formed by Homodimerization (Green and White Surface Structures) (A) Ornithine in the Active Site of ODC, Cys-360 highlighted in yellow (B) Product of Eflornithine Decarboxylation bound to Cys 360 (highlighted in yellow). The pyrroline ring blocks ornithine from entering the active site[31]

History

editEflornithine was initially developed for cancer treatment at Merrell Dow Research Institute in the late 1970s, but was found to be ineffective in treating malignancies. However, it was discovered to be highly effective in reducing hair growth,[32] as well as in the treatment of African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness),[33] especially the West African form (Trypanosoma brucei gambiense).

Hirsutism

editIn the 1980s, Gillette was awarded a patent for the discovery that topical application of eflornithine HCl cream inhibits hair growth. In the 1990s, Gillette conducted dose-ranging studies with eflornithine in hirsute women that demonstrated that the drug slows the rate of facial hair growth. Gillette then filed a patent for the formulation of eflornithine cream. In July 2000, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted a New Drug Application for Vaniqa. The following year, the European Commission issued its Marketing Authorisation.[citation needed]

Sleeping sickness treatment

editThe drug was registered for the treatment of gambiense sleeping sickness on 28 November 1990.[11] However, in 1995 Aventis (now Sanofi-Aventis) stopped producing the drug, whose main market was African countries, because it did not make a profit.[34]

In 2001, Aventis and the WHO formed a five-year partnership, during which more than 320,000 vials of pentamidine, over 420,000 vials of melarsoprol, and over 200,000 bottles of eflornithine were produced by Aventis, to be given to the WHO and distributed by the association Médecins sans Frontières (also known as Doctors Without Borders)[35][36] in countries where sleeping sickness is endemic.

According to Médecins sans Frontières, this only happened after "years of international pressure," and coinciding with the period when media attention was generated because of the launch of another eflornithine-based product (Vaniqa, for the prevention of facial-hair in women),[34] while its life-saving formulation (for sleeping sickness) was not being produced.

From 2001 (when production was restarted) through 2006, 14 million diagnoses were made. This greatly contributed to stemming the spread of sleeping sickness, and to saving nearly 110,000 lives.[citation needed]

Society and culture

editAvailable forms

editVaniqa is a cream, which is white to off-white in colour. It is supplied in tubes of 30 g and 60 g in Europe.[28] Vaniqa contains 15% w/w eflornithine hydrochloride monohydrate, corresponding to 11.5% w/w anhydrous eflornithine (EU), respectively 13.9% w/w anhydrous eflornithine hydrochloride (U.S.), in a cream for topical administration.[citation needed]

Ornidyl, intended for injection, was supplied in the strength of 200 mg eflornithine hydrochloride per ml.[37]

Market

editVaniqa, granted marketing approval by the US FDA, as well as by the European Commission[38] among others, is currently the only topical prescription treatment that slows the growth of facial hair.[19] Besides being a non-mechanical and non-cosmetic treatment, it is the only non-hormonal and non-systemic prescription option available for women with facial hirsutism.[18] Vaniqa is marketed by Almirall in Europe, SkinMedica in the US, Triton in Canada, Medison in Israel, and Menarini in Australia.[38]

Ornidyl, the injectable form of eflornithine hydrochloride, is licensed by Sanofi-Aventis, but is currently discontinued in the US.[39]

Research

editChemo preventative therapy

editIt has been noted that ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) exhibits high activity in tumor cells, promoting cell growth and division, while absence of ODC activity leads to depletion of putrescine, causing impairment of RNA and DNA synthesis. Typically, drugs that inhibit cell growth are considered candidates for cancer therapy, so eflornithine was naturally believed to have potential utility as an anti-cancer agent. By inhibiting ODC, eflornithine inhibits cell growth and division of both cancerous and noncancerous cells.[citation needed]

However, several clinical trials demonstrated minor results.[40] It was found that inhibition of ODC by eflornithine does not kill proliferating cells, making eflornithine ineffective as a chemotherapeutic agent. The inhibition of the formation of polyamines by ODC activity can be ameliorated by dietary and bacterial means because high concentrations are found in cheese, red meat, and some intestinal bacteria, providing reserves if ODC is inhibited.[41] Although the role of polyamines in carcinogenesis is still unclear, polyamine synthesis has been supported to be more of a causative agent rather than an associative effect in cancer.[40]

Other studies have suggested that eflornithine can still aid in some chemoprevention by lowering polyamine levels in colorectal mucosa, with additional strong preclinical evidence available for application of eflornithine in colorectal and skin carcinogenesis.[40][41] This has made eflornithine a supported chemopreventive therapy specifically for colon cancer in combination with other medications. Several additional studies have found that eflornithine in combination with other compounds decreases the carcinogen concentrations of ethylnitrosourea, dimethylhydrazine, azoxymethane, methylnitrosourea, and hydroxybutylnitrosamine in the brain, spinal cord, intestine, mammary gland, and urinary bladder.[41]

Veterinary uses

editEflornithine is effective in mice.[42][43] Bacchi et al. 1980 found the drug to be curative in T. b. brucei infection of mouse and it is generally without toxicity.[42] Klug et al. 2016[42] are of the opinion that this demonstrates good promise for oral treatment. However although Jansson et al. 2008 also effectively treated mice with it they found the pharmacokinetics of oral administration in rats very negative.[43] Brun et al. 2010[43] are of the opinion that Jansson's results have killed the prospects for oral treatment.

References

edit- ^ a b c "Vaniqa- eflornithine hydrochloride cream". DailyMed. 18 September 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "Iwilfin- eflornithine hydrochloride tablet". DailyMed. 21 December 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ a b c "Eflornithine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "CDC - African Trypanosomiasis - Resources for Health Professionals". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10 August 2016. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ Steverding D (2016). "Sleeping Sickness and Nagana Disease Caused by Trypanosoma brucei". In Marcondes CB (ed.). Arthropod Borne Diseases. Springer. p. 292. ISBN 9783319138848. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness)". World Health Organization. February 2016. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Babokhov P, Sanyaolu AO, Oyibo WA, Fagbenro-Beyioku AF, Iriemenam NC (July 2013). "A current analysis of chemotherapy strategies for the treatment of human African trypanosomiasis". Pathogens and Global Health. 107 (5): 242–252. doi:10.1179/2047773213Y.0000000105. PMC 4001453. PMID 23916333.

- ^ Priotto G, Fogg C, Balasegaram M, Erphas O, Louga A, Checchi F, et al. (December 2006). "Three drug combinations for late-stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense sleeping sickness: a randomized clinical trial in Uganda". PLOS Clinical Trials. 1 (8): e39. doi:10.1371/journal.pctr.0010039. PMC 1687208. PMID 17160135.

- ^ a b Lutje V, Seixas J, Kennedy A (June 2013). "Chemotherapy for second-stage human African trypanosomiasis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (6): CD006201. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006201.pub3. PMC 6532745. PMID 23807762.

- ^ Chappuis F, Udayraj N, Stietenroth K, Meussen A, Bovier PA (September 2005). "Eflornithine is safer than melarsoprol for the treatment of second-stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense human African trypanosomiasis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (5): 748–751. doi:10.1086/432576. PMID 16080099.

- ^ a b c d Vincent IM, Creek D, Watson DG, Kamleh MA, Woods DJ, Wong PE, et al. (November 2010). "A molecular mechanism for eflornithine resistance in African trypanosomes". PLOS Pathogens. 6 (11): e1001204. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001204. PMC 2991269. PMID 21124824.

- ^ "Nifurtimox-eflornithine combination treatment for sleeping sickness (human African trypanosomiasis): WHO wraps up training of key health care personnel". World Health Organization. 23 March 2010. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014.

- ^ Franco JR, Simarro PP, Diarra A, Ruiz-Postigo JA, Samo M, Jannin JG (2012). "Monitoring the use of nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy (NECT) in the treatment of second stage gambiense human African trypanosomiasis". Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine. 3: 93–101. doi:10.2147/RRTM.S34399. PMC 6067772. PMID 30100776.

- ^ Sayé M, Miranda MR, di Girolamo F, de los Milagros Cámara M, Pereira CA (2014). "Proline modulates the Trypanosoma cruzi resistance to reactive oxygen species and drugs through a novel D, L-proline transporter". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e92028. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...992028S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092028. PMC 3956872. PMID 24637744.

- ^ Barrett MP, Boykin DW, Brun R, Tidwell RR (December 2007). "Human African trypanosomiasis: pharmacological re-engagement with a neglected disease". British Journal of Pharmacology. 152 (8): 1155–71. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707354. PMC 2441931. PMID 17618313.

- ^ a b "NHS and UKMi New Medicines Profile" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2010.

- ^ a b Balfour JA, McClellan K (June 2001). "Topical eflornithine". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2 (3): 197–201, discussion 202. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102030-00009. PMID 11705097. S2CID 26181011.

- ^ Schrode K, Huber F, Staszak J, et al. (The Eflornithine Study Group) (March 2000). Evaluation of the long-term safety of eflornithine 15% cream in the treatment of women with excessive facial hair, Poster 294. 58th Annual Meeting American Academy of Dermatology. San Francisco; USA.

- ^ Schrode K, Huber F, Staszak J, Altman DJ, Shander D, Morton J, et al. (The Eflornithine Study Group) (March 2000). Randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled safety and efficacy evaluation of eflornithine 15% cream in the treatment of women with excessive facial hair. Poster 291. 58th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Dermatology. San Francisco; USA.

- ^ Wolf JE, Shander D, Huber F, Jackson J, Lin CS, Mathes BM, et al. (January 2007). "Randomized, double-blind clinical evaluation of the efficacy and safety of topical eflornithine HCl 13.9% cream in the treatment of women with facial hair". International Journal of Dermatology. 46 (1): 94–98. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.03079.x. PMID 17214730. S2CID 10795478.

- ^ Jackson J, Caro JJ, Caro G, Garfield F, Huber F, Zhou W, et al. (flornithine HCl Study Group) (September 2007). "The effect of eflornithine 13.9% cream on the bother and discomfort due to hirsutism". International Journal of Dermatology. 46 (9): 976–81. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03270.x. PMID 17822506. S2CID 25986442.

- ^ a b c "Vaniqa Summary of Product Characteristics 2008". Archived from the original on 5 December 2009.

- ^ a b "Ornidyl Drug Information". Archived from the original on 7 June 2011.

- ^ Malhotra B, Noveck R, Behr D, Palmisano M (September 2001). "Percutaneous absorption and pharmacokinetics of eflornithine HCl 13.9% cream in women with unwanted facial hair". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 41 (9): 972–978. doi:10.1177/009127000104100907. PMID 11549102. Archived from the original on 12 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Vaniqa Product Monograph (PDF). Cipher Pharmaceuticals Inc. 8 July 2015 – via Drug and Health Product Register, Canada.

- ^ a b c "Vaniqa US Patient Information Leaflet" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2010.

- ^ a b Brooks HB, Phillips MA (December 1997). "Characterization of the reaction mechanism for Trypanosoma brucei ornithine decarboxylase by multiwavelength stopped-flow spectroscopy". Biochemistry. 36 (49): 15147–15155. doi:10.1021/bi971652b. PMID 9398243.

- ^ a b c Poulin R, Lu L, Ackermann B, Bey P, Pegg AE (January 1992). "Mechanism of the irreversible inactivation of mouse ornithine decarboxylase by alpha-difluoromethylornithine. Characterization of sequences at the inhibitor and coenzyme binding sites". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 267 (1): 150–158. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)48472-4. PMID 1730582.

- ^ Grishin NV, Osterman AL, Brooks HB, Phillips MA, Goldsmith EJ (November 1999). "X-ray structure of ornithine decarboxylase from Trypanosoma brucei: the native structure and the structure in complex with alpha-difluoromethylornithine". Biochemistry. 38 (46): 15174–15184. doi:10.1021/bi9915115. PMID 10563800.

- ^ Wolf JE, Shander D, Huber F, Jackson J, Lin CS, Mathes BM, et al. (January 2007). "Randomized, double-blind clinical evaluation of the efficacy and safety of topical eflornithine HCl 13.9% cream in the treatment of women with facial hair". International Journal of Dermatology. 46 (1): 94–98. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.03079.x. PMID 17214730. S2CID 10795478.

- ^ Pepin J, Milord F, Guern C, Schechter PJ (December 1987). "Difluoromethylornithine for arseno-resistant Trypanosoma brucei gambiense sleeping sickness". Lancet. 2 (8573): 1431–1433. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(87)91131-7. PMID 2891995. S2CID 41019313.

- ^ a b "Supply of sleeping sickness drugs confirmed". Médecins Sans Frontières. 3 May 2001. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015.

- ^ "Sanofi-Aventis Access to Medicines Brochure" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2008.

- ^ "IFPMA Health Initiatives: Sleeping Sickness". Archived from the original on 29 August 2006.

- ^ "Ornidyl facts". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- ^ a b Vaniqa Training Programme Module 5 (Report).

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Raul F (April 2007). "Revival of 2-(difluoromethyl)ornithine (DFMO), an inhibitor of polyamine biosynthesis, as a cancer chemopreventive agent". Biochemical Society Transactions. 35 (Pt 2): 353–5. doi:10.1042/BST0350353. PMID 17371277.

- ^ a b c Gerner EW, Meyskens FL (October 2004). "Polyamines and cancer: old molecules, new understanding". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 4 (10): 781–792. doi:10.1038/nrc1454. PMID 15510159. S2CID 37647479.

- ^ a b c Klug DM, Gelb MH, Pollastri MP (June 2016). "Repurposing strategies for tropical disease drug discovery". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 26 (11). Elsevier: 2569–2576. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.03.103. PMC 4853260. PMID 27080183. NIHMS 777366.

- ^ a b c Büscher P, Cecchi G, Jamonneau V, Priotto G (November 2017). "Human African trypanosomiasis". Lancet. 390 (10110). Elsevier: 2397–2409. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60829-1. PMID 28673422. S2CID 4853616.

External links

edit- Media related to Eflornithine at Wikimedia Commons

- Clinical trial number NCT02395666 for "Preventative Trial of Difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) in High Risk Patients With Neuroblastoma That is in Remission" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- Clinical trial number NCT02679144 for "Neuroblastoma Maintenance Therapy Trial (NMTT)" at ClinicalTrials.gov