The 1860 civil conflict in Mount Lebanon and Damascus, also known as the 1860 Syrian Civil War and the 1860 Christian–Druze war, was a civil conflict in Mount Lebanon during Ottoman rule in 1860–1861 fought mainly between the local Druze and Christians.[4] Following decisive Druze victories and massacres against the Christians, the conflict spilled over into other parts of Ottoman Syria, particularly Damascus, where thousands of Christian residents were killed by Druze militiamen. The fighting precipitated a French-led international military intervention.[1]

| 1860 civil conflict in Mount Lebanon and Damascus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

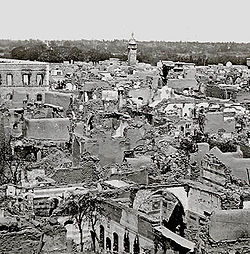

The ruins of the Christian quarter of Damascus in 1860 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Maronites and allies

Supported by: |

Rural Druze clans

Supported by:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 50,000 (claimed) | c. 12,000 (Druze) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

Background

editThe relationship between the Druze and Christians has been characterized by harmony and coexistence,[6][7][8][5] with amicable relations between the two groups prevailing throughout history. After the Shihab dynasty converted to Christianity,[9] the Druze lost most of their political and feudal powers.

On 3 September 1840, Bashir Shihab III was appointed emir of the Mount Lebanon Emirate by the Ottoman Sultan Abdulmejid I, succeeding his distant cousin, the once-powerful Bashir Shihab II. Geographically, the Mount Lebanon Emirate corresponded with the central part of present-day Lebanon, which historically has had a Christian and Druze majority. In practice, the terms "Lebanon" and "Mount Lebanon" tended to be used interchangeably by historians until the formal establishment of the post-World War I Mandate of Lebanon.[citation needed]

Bitter conflicts between Christians and Druzes, which had been simmering under Ibrahim Pasha's rule (mostly centred on the firmans of 1839 and, more decisively, of 1856, which equalised the status of Muslim and non-Muslim subjects, the former resenting their implied loss of superiority)[dubious – discuss] resurfaced under the new emir. The sultan deposed Bashir III on 13 January 1842 and appointed Omar Pasha as governor of Mount Lebanon. Representatives of the European powers proposed to the sultan that Mount Lebanon be partitioned into Christian and Druze sections. On 7 December 1842, the sultan adopted the proposal and asked the governor of Damascus to divide the region into two districts: a northern district under a Christian deputy governor and a southern district under a Druze deputy governor. The arrangement came to be known as the "Double Qaimaqamate". Both officials were to be responsible to the governor of Sidon, who resided in Beirut. The Beirut-Damascus highway was the dividing line between the two districts.[10]

While the Ottoman authorities pursued a divide-and-rule strategy, various European powers established alliances with the various religious groups in the region. The French established an alliance with the Lebanese Christians, while the Druze formalized an alliance with the British, allowing them to send Protestant missionaries into the region.[10] The increasing tensions led to an outbreak of conflict between Christians and Druzes as early as May 1845. Consequently, the European great powers requested for the Ottoman sultan to establish order in Lebanon, and he attempted to do so by establishing a new council in each of the districts. Composed of members of the various religious communities, the councils were intended to assist the deputy governor.[10]

Leadup to war

editThe system failed to keep order when the peasants of Keserwan, overburdened by heavy taxes, rebelled against the feudal practices that prevailed in Mount Lebanon. In 1858, Tanyus Shahin, a Maronite Christian peasant leader, demanded for the feudal class to abolish its privileges. The demand was refused, and the peasants began to prepare for a revolt. In January 1859, an armed uprising, led by Shahin, was launched against the Maronite Khazen muqata'jis (feudal lords) of Keserwan. Khazen lands were pillaged and homes burned. After driving the Maronite feudal lords out of Keserwan and seizing their land and property, the insurgent peasants set up their own rule.[citation needed][11][12] The Keserwan uprising had a revolutionary effect on other regions in Lebanon. The disturbances spread to Latakia and to central Mount Lebanon. Maronite peasants, actively supported by their clergy, began to prepare for an armed uprising against their Druze lords.[citation needed][11] In turn, the Druze lords, who had been hesitant to confront the growing assertiveness of the Maronite peasantry due to the numerical imbalance in the Maronites' favour,[10] began to arm Druze irregulars.[11]

In August 1859, a brawl occurred between Druze and Maronites in the Metn area in the Christian sector of the Qaimaqamate. The dispute enabled Maronite bishop Tobia Aoun to mobilise his Beirut-based central committee to intervene in the matter. Soon, a Druze muqata'ji of the Yazbaki faction, Yusuf Abd al-Malik, and his fighters intervened in a brawl between young Maronite and Druze men in the vicinity of the Metn village of Beit Mery, which resulted in 20 fatalities. The Druze lords began making war preparations, allegedly in co-ordination with the local Ottoman authorities, while Bishop Aoun oversaw the distribution of weapons to Maronite peasants. According to the historian William Harris, the Christians of Mount Lebanon felt "buoyed by their local numerical superiority, yet despondent because of the hostile Muslim mood in Syria" in the aftermath of the Ottoman Empire's reforms.[10]

In March, April and May 1860, numerous acts of murder, looting and skirmishing took place across the mixed Christian-Druze districts of southern Mount Lebanon in the Druze-run sector of the Double Qaimaqamate.[13] According to the historian Leila Terazi Fawaz, the initial acts were "random and unpredictable enough to seem more the acts of lawless men than a calculated war against other sects, especially since banditry was always part of the objective".[13]

In March, the father of a Catholic monastery[clarification needed] in Aammiq was murdered and the monastery looted, and soon, a Druze man from Ainab allegedly murdered a Christian man from Abadiyeh. Those acts fuelled a cycle of revenge attacks that significantly increased in frequency by April.[14]

In April, two Druze men were murdered in the vicinity of Beirut, followed by the killing of three Christians outside of Sidon. Two Christians from Jezzine were murdered at Khan Iqlim al-Shumar by Druze from Hasbaya on 26 April, and the next day, another four Christians were murdered in Katuli. On 11 May, Christians from Katuli murdered two Druzes at the Nahr al-Assal River, and three days later, two Druzes from Chouf were murdered near Sidon. The tit-for-tat killings continued, rendering most of the roads of Mount Lebanon unsafe for travellers.

Around the end of May, Christians reported to the European consuls that killings of their co-religionists occurred in the districts of Beqaa, Arqub and Gharb. The Maronite clergy communicated to one another their increasing concerns on the violence and the need to end it, but some clergymen believed that the cycle of retaliatory attacks would not stop.[15]

With Maronite militias launching raids into Metn and Shahin's forces making incursions into the Gharb area west of Beirut, the Druze muqata'jis held a war council in Moukhtara in which the Jumblatti factions and their more hawkish Yazbaki counterparts agreed to appoint Sa'id Jumblatt as their overall commander.[10]

Civil war in Mount Lebanon and environs

editOutbreak of war

editMost sources put the start of the war at 27 May, while the British consul considered 29 May the actual start of full-fledged conflict. The first major outbreak of violence occurred when a 250-strong Maronite militia from Keserwan led by Taniyus Shahin went to collect the silk harvest from Naccache, but instead of returning to Keserwan, proceeded to Baabda in the al-Sahil district near Beirut. The local Druze leadership considered the Maronite mobilization at Baabda to be a provocation to the Druze in the mixed Metn district, while the Maronites saw the garrisoning of Ottoman troops under Khurshid Pasha near Naccache on 26 May as a prelude to a Druze assault. The Ottoman garrison established itself at Hazmiyeh with the support of the European consuls in order to bring order to Mount Lebanon. However, the Maronites considered it a threat since they viewed the Ottomans as allies of the Druze.[16]

On 29 May, Keserwani Maronites raided the mixed villages of Qarnayel, Btekhnay and Salima and forced out their Druze residents.[17][18] The tension broke out into open conflict later that day during a Druze assault against the mixed village of Beit Mery,[17] with the village's Druze and Christian residents subsequently calling for support from their co-religionists in Abadiyeh and al-Sahil, respectively.[16] The Druze, backed by an Ottoman commander of irregulars named Ibrahim Agha,[16] and Maronite fighters burned down the houses of the rival sect in Beit Mery. The Maronite fighters defeated the Druze and Ibrahim Agha at Beit Mery before withdrawing from the village.[19]

On 30 May, the Keserwani Maronite militiamen attempted to renew their assault against Beit Mery, but were countered by 1,800-2,000 Druze militiamen led by the Talhuq and Abu Nakad clans on the way, prompting previously neutral Maronites from Baabda, Wadi Shahrur, Hadath and elsewhere in al-Sahil to join the fighting. Although casualties among the Christian militiamen were relatively low during the fighting on 30 May, in the renewed battle on 31 May, the 200-strong Maronite force was routed at Beit Mery and forced to retreat to Brummana. By the day's end, the Druze fighters were in complete control of Metn, where clashes were widespread, and between 35 and 40 Maronite-majority villages were set alight and some 600 Maronites in the district slain.[19]

Also on 30 May,[19] full-fledged fighting between Druze and Christians occurred in the area of Zahle, when a 200-strong Druze force led by Ali ibn Khattar Imad confronted 400 local Christian fighters at the village of Dahr al-Baidar, prompting Christian militiamen from nearby Zahle to join the fighting. Imad's men retreated to Ain Dara, where the Christians followed them before being defeated.[20] Ali Imad died of his wounds on 3 June; consequently, a 600-strong Druze force was mobilized under the command of his father Khattar Imad. Some 3,000 Christian fighters, predominantly from Zahle, met Khattar's forces near Ain Dara where a major battle took place. The Druze experienced twice as many casualties as the Christians, but ultimately forced the Christians to retreat to Zahle.[20] Between 29 and 31 May, 60 villages were destroyed in the vicinity of Beirut,[11] and 33 Christians and 48 Druzes were murdered.[21]

In the last days of May, Druze forces under the command of Bashir Nakad and backed by the Imad and Jumblatt clans besieged Deir al-Qamar. In the first days of June, reports from the town to European consuls reported that starvation was beginning to set in. A relief supply of grain and flour sent by the Ottoman general Khurshid Pasha apparently did not reach the town. Bashir's forces, numbering some 3,000 Druze fighters, launched an assault on Deir al-Qamar on 2 June and another assault the next day. The Christian defenders in Deir al-Qamar initially put up stiff resistance and inflicted heavy casualties on the Druze forces, who managed to raze the town's outskirts.[22] After eight hours of the Druze assault, Deir al-Qamar surrendered on 3 June, partially as a result of internal divisions among the town's Christian militia. Fatality reports ranged from 70 to 100 slain Druze and 17 to 25 Christians. Following its capture, the Druze plundered Deir al-Qamar until 6 June and destroyed 130 houses.[22] Around half of the town's Christian residents had remained neutral and appealed for protection by the Druze, with whom many had long maintained social and commercial ties.[23]

Wadi al-Taym clashes and Hasbaya massacre

editUnlike their co-religionists elsewhere in Syria, the Greek Orthodox inhabitants of Wadi al-Taym were generally aligned with the Maronites of Mount Lebanon, due to shared opposition to Protestant missionary activity, and were loyal to their lords, the Sunni Muslim Shihab emirs of Rashaya and Hasbaya.[24] Fighting between the Shihab emirs led by Sa'ad al-Din Shihab and the Druze led by Sa'id al-Shams and Sa'id Jumblatt had been going on since the last days of May, particularly in Deir Mimas.[23] The clashes led to shoot-outs in Hasbaya between Christians and Druze peasant fighters from various other Wadi al-Taym villages. Before casualties became heavy, emergency Ottoman reinforcements led by Yusuf Agha intervened to back the Ottoman garrison led by Uthman Bey, and stopped the fighting in Hasbaya.[23] Meanwhile, fighting between Druzes and Christians had broken out in nearby Shebaa, prompting Uthman Bey to intervene in the village and then confer with Druze sheikhs in Marj Shwaya ostensibly to gain assurances from them that they would cease hostilities. Not long after Uthman Bey assured the Christians of Hasbaya that Druze attacks would end, Druze forces set fire to a Christian village in Wadi al-Taym and proceeded to assault Hasbaya, where Christians fleeing the clashes had been seeking shelter.[25]

At the advice of Uthman Bey, a large part of Hasbaya's Christian community took refuge in Hasbaya's government house, along with several Shihabi family members, and surrendered their weapons, which numbered around 500 guns. The surrendered guns were soon looted by the Druze and according to the British consul, this had been Uthman Bey's actual intention.[25] The Christians of Hasbaya, along with 150 Christian refugees from Qaraoun, had taken shelter in the government house on 3 June. Some 400 sheltered in the home of Sa'id Jumblatt's sister Nayifa, due to her concerns that the gathering of so many Christians at government house would put so many of their lives in danger. Many Christians did not trust Nayifa due to her frequent hosting of Uthman Bey, who the local Christians increasingly lost trust of, and her family's leadership of the Druzes.[26]

The Druzes of Wadi al-Taym had been receiving numerous reinforcements from Majdal Shams, Iqlim al-Ballan and the Hauran plain, and were quietly backed by Uthman Bey. Led by commanders Ali Bey Hamada, Kenj Ahmad and Hasan Agha Tawil, the Druze forces assembled around Hasbaya on 3 June. Several hundred (possibly up to 1,000) largely disorganized and inexperienced Christian men from Hasbaya mobilized as well. After heavy fighting that day, the Christians, who suffered 26 casualties, managed to briefly push back the Druzes, who suffered 130 fatalities, and proceeded to burn down Druze homes in the area. On 4 June, the much larger Druze force defeated the Christians after an hour-long assault and the Christian forces fled. The Christians had apparently been waiting for Ottoman troops to arrive and protect them as they were promised, but this did not materialize.[27]

Following the Druzes' capture of Hasbaya, their forces proceeded to assault the government house. At first, the Druzes sought out and murdered 17 Shihabi men, including Emir Sa'ad al-Din, who was decapitated and thrown off the three-story building's rooftop. The Druze fighters then began killing the Christians who had taken refuge there. Druze fighters massacred about 1,000 Christian males, adults and children, while sparing the women.[27] According to an account by a Christian survivor, "the men were slaughtered in the embrace of their wives and the children at the breasts of their mothers".[27] About 40-50 men survived after managing to escape.[27] The 400 Christians who had sheltered with Nayifa Jumblatt survived because she had them relocated initially to the Jumblatt stronghold of Moukhtara and from there to the port of Sidon, from which they were able to make it to Beirut on a Royal Navy warship.[28]

Assault on Rashaya

editIn the days after the Druze victory at Hasbaya, violence raged in the southern Beqaa Valley. The hostilities were set off after two Druze men from Kfar Qouq were arrested by the authorities for their suspected role in the deaths of two Christians from Dahr al-Ahmar who were shot down as they were transporting clay pots on their way to Damascus. The Druze men were quickly released by the Ottomans after protests by the local Druze community. The local Druze were angry at the Christians for complaining to the authorities, which led to the arrests, and launched an attack on Dahr al-Ahmar. On 8 June Christians from Dahr al-Ahmar and the vicinity fled to Rashaya, which had an Ottoman garrison, for protection.[28]

As the Christians fled to Rashaya, Druzes began burning down the homes they left behind and assaulted the Christian villages of Kfar Mishki, Beit Lahia and Hawush. The Christians received assurances of safety from Emir Ali Shihab, governor of Rashaya, and the Druze al-Aryan family, which held significant influence in the town. About 150 took refuge in the government house and set up barricades on the streets leading to the building as additional security measures. That same day, a Druze force attacked the town and burnt down Christian homes, forcing many other local Christians to seek shelter in the government house. Several Christians were murdered before the Druze force withdrew after a meeting with the Ottoman authorities at Ziltatiat. The Christians remained in the government house upon the counsel of the local Ottoman garrison's commander.[29]

By 11 June, a 5,000-strong Druze force assembled outside Rashaya consisting of local Druze militiamen, the Druze force from the previous Hasbaya battle and Druze troops under the command of Isma'il al-Atrash. Al-Atrash's men had attacked several Christian villages in the Anti-Lebanon Mountains on their way to Rashaya. That day, the Druze force split into two main contingents, with one attacking the Christian village of Aya and the other storming Rashaya. The Shihab emirs of Rashaya, with the exception of two, were slain. The Druze assaulted the government house and murdered the men inside, including priests. The combined Christian fatalities from the massacre at Hasbaya and the assault on Rashaya and its neighboring villages were roughly 1,800.[29]

Battle of Zahlé

editThe Druze followed up on their victory at Rashaya by raiding villages in the central Beqaa Valley and the vicinity of Baalbek together with Shia Muslim peasants and irregulars, guided by the Harfush clan. While the Harfushes continued to assault Baalbek, the Druze proceeded back south towards Zahlé, which at that time remained the last major Christian stronghold.[29] The Zahalni Christians, largely led by Abdallah Abu Khatir, appealed for support from Maronite militia leaders in Kesrawan and Metn, namely Taniyus Shahin of Reifun, Youssef Bey Karam of Ehden and Yusuf al-Shantiri of Metn. Shahin feared antagonizing the Ottoman authorities and did not respond to the appeal, while al-Shantiri preferred to wait and assess any moves made by Shahin or Karam first. Karam responded positively to the appeal and assembled a 4,000-strong force, but it did not make it further than the Metn village of Bikfaya. After the conflict's end, Karam claimed his abrupt halt was due to prohibitions on further advances by the French consul and the Ottoman authorities.[30]

The Christian force assembled in Zahlé numbered around 4,000 men, mostly from Zahlé, but also 400 cavalry from Baskinta and a smaller force from Metn. They stockpiled ammunition and had hundreds of horses available for battle. The Zahalni militiamen prepared the town's defences by digging deep trenches around it, building a brick wall at its southern edge and fortifying parts of the town's narrow roads and paths. They stocked foodstuffs and other supplies, and townspeople hid any valuable items in their possession.[31] Meanwhile, Druze forces from Wadi al-Taym, Rashaya, Chouf and the Hauran were assembling in Zahlé's vicinity, using the nearby mixed village of Qabb Ilyas to Zahlé's south, as their headquarters.[30] Zahalni Christian forces launched an assault against Qabb Ilyas on 14 June. According to an account of that confrontation, the Christians fought "without discipline" and were "heedless of danger", spreading themselves thin across the plains of Qabb Ilyas, with fighters taking up uncoordinated positions and firing their weapons. The Druze defenders forced them to retreat to Zahlé. The Zahalni repeated their assault a few days later, but were again repulsed.[31]

On 18 June, Druze forces under Khattar Imad's command and reinforced by Shia peasants and Sunni Sardiyah Bedouin cavalry from Hauran (3,000 men altogether) began their assault on Zahle, some of whose defenders were feuding among each other at the time of the attack. The Druze assault was well-planned according to accounts of the battle, with some of their forces attacking Zahle's well-defended eastern, southern and western sides, while Imad's contingent launched a surprise attack against the town from the north. The Zahalni had not concentrated their fortifications at Zahle's north because they expected that side of town to be safe due to the heavy Christian presence there. Furthermore, they were still expecting Karam's men to be arriving from the north side (they had not yet been notified of his troops' halt at Bikfaya).[31] Imad disguised his contingent as Christians by adorning them with crosses and Christian flags taken from slain Christian fighters in previous battles. Thus, when Imad and his men approached Zahle from the north, its defenders enthusiastically welcomed them, believing them to be Karam's men.[32]

As Imad's Druze forces entered Zahle, they proceeded to burn down its northern neighborhoods. When Druze forces commanded by Isma'il al-Atrash saw the flames emanating from northern Zahle, they stormed the town. Within hours, Zahle was under Druze control. Zahle's residents panicked and fled the town for Metn, Keserwan and al-Sahil. By 19 June, the town was emptied of its inhabitants. The Christians suffered between 40 and 900 casualties, while the Druze and their allies suffered between 100 and 1,500 casualties. The Druze agreed beforehand not to loot Zahle, but the Sardiyah Bedouin tribesmen plundered the town, taking money, horses and jewellery.[32]

The outcome at Zahle held enormous significance for both sides in the war. For the Christians, the fall of the strongest Christian town meant the loss of their principal support base, as the Zahalni supported other Christians in many earlier battles during the conflict. Zahle was believed by many Christians in Mount Lebanon to be unconquerable. According to the British consul, the Christian defeat at Zahle caused many Christians to consequently want to flee Ottoman Syria. The Druze victory at Zahle was a major morale boost for their forces since the fall of Zahle effectively symbolized their total victory over the Christians of Mount Lebanon, which they then controlled indisputably. It was also a cause for celebration among Muslims of all sects in Ottoman Syria because many Muslims viewed its inhabitants as arrogant, and reportedly "suffered from the people of Zahle and heard of their sly deeds", according to the Damascene notable Sayyid Muhammad Abu'l Su'ud al-Hasibi, who condemned what he saw as Druze and Muslim excesses during the conflict. The Muslims of Damascus held celebrations in the city after the fall of Zahle.[32]

Following Zahle's fall, groups of Sunni and Shia Muslims from Baalbek used the opportunity to settle scores with local Christians and plunder the town and its vicinity. Up to 34 Christian villages in the Beqaa Valley were plundered and burned, with many houses and churches destroyed, and harvests and livestock taken.[33] The Shia Harfush clan led the siege and assault on Baalbek, attacking the Ottoman garrison there commanded by Husni Bey and the headquarters of the district governor, Faris Agha Qadro,[33] killing several of the latter's employees. The Kurdish irregulars led Hassan Agha Yazigi that were dispatched by the Ottoman governor of Damascus did not attempt to relieve the siege. Baalbek was largely destroyed and Yazigi's irregulars would later participate in the town's plunder.[34]

Massacre of Deir al-Qamar

editDeir al-Qamar had already been captured by Druze forces and its residents had consistently appealed for protection from their friends among the local Druze and from the Ottoman authorities. Nonetheless, following their decisive victory at Zahle, the Druze renewed their assault against Deir al-Qamar on 20 June.[34] In the weeks prior, some of the town's wealthier residents managed to leave for Beirut or gained Sa'id Jumblatt's protection in Moukhtara. However, thousands of Christians remained in Deir al-Qamar and the Druze militiamen were preventing many from leaving. As Druze fighters moved in on the town, ostensibly guarding homes and shops, they proceeded to loot many buildings that had been abandoned by their patrons.[35] The Christian residents did not put up armed resistance against the Druze fighters, and sometime before 20 June the Christians had been disarmed either at the counsel of the district governor Mustafa Shukri Effendi or an Ottoman general from the Beirut garrison named Tahir Pasha. The Ottomans' advice to the Christians regarding disarmament was that it would help in not provoking the Druze.[36]

On the evening of 19 June, a Christian resident and a priest were killed outside the government house in Deir al-Qamar, where thousands of residents had begun taking refuge. Hundreds of others took shelter in the abandoned Ottoman barracks at Beit ed-Dine or the district governor's residence. Meanwhile, Druze fighters from Moukhtara, Baakline, Ain al-Tineh, Arqub district, Manasif district, Boutmeh, Jdaideh, Shahahir, and Ammatour were streaming into Deir al-Qamar from several directions. At least part of these forces were commanded by Sheikh Qasim Imad. The roughly 4,000 Ottoman troops stationed in Deir al-Qamar did not stop the incoming Druzes. On the morning of 20 June, the Druzes assaulted the government house and proceeded to kill the males taking refuge in it, all of whom were unarmed. European consuls who witnessed the killings or their aftermath reported that many women were assaulted as well in an unprecedented manner. Afterwards, the Druzes plundered Deir al-Qamar, which was well known for being wealthy. Unlike in Zahle, the Druzes looted large quantities of horses, livestock, jewellery and other goods. Large parts of the town were burned down. Other Christians were killed throughout Deir al-Qamar.[37]

Nearby Beit ed-Dine and its countryside was also sacked.[38] The plunder in Deir al-Qamar ended on 23 June,[39] after intervention by Sa'id Jumblatt, Bashir Nakad, sheikhs from the Hamada clan, and an Ottoman colonel. By the end of the fighting, much of Deir al-Qamar, which was the most prosperous town of the predominantly Druze Chouf district, was in ruins, and corpses, some mutilated, were left throughout the town's streets, markets, houses and Ottoman government buildings and military installations.[38] Between 1,200 and 2,200 Christians had been killed in the onslaught and many more had fled. By October 1860, Deir al-Qamar's population which had been roughly 10,000 before the conflict, had been reduced to 400.[39] According to Fawaz, the ceasefire negotiated between by the Druze sheikhs and the authorities marked the "end to the most violent phase of the civil war" in Mount Lebanon.[40]

Casualties in Mount Lebanon and environs

editMost sources put the figure of those killed between 7,000 and 11,000, with some claiming over 20,000[41] or 25,000.[42] A letter in the English Daily News in July 1860 stated that between 7,000 and 8,000 had been murdered, 5,000 widowed, and 16,000 orphaned. James Lewis Farley, in a letter, spoke of 326 villages, 560 churches, 28 colleges, 42 convents, and 9 other religious establishments having been totally destroyed. Churchill puts the figures at 11,000 murdered, 100,000 refugees, 20,000 widows and orphans, 3,000 habitations burnt to the ground, and 4,000 perishing from destitution.[41] Other estimates claim 380 Christian villages were destroyed.[11]

Massacre of Christians in Damascus

editAn anti-Christian pogrom in Damascus, referred to popularly as Ṭoshat an-Naṣṣāra (طوشة النصارى,[43][44] lit. 'Riot of the Christians'), broke out in July when a crowd of Druzes, Bedouins, Arab Muslim city commoners, and Kurdish auxiliary forces attacked the inner city Christian neighborhood of Bab Tuma, resulting in the death of thousands of Christians.[45]

Early tensions in the city

editThe early reports of the war in Mount Lebanon received in Damascus were generally sketchy but evolved into more graphic reports from Beirut-based newspapers. The reports were often distorted or amplified in mosques, churches, marketplaces and in neighborhoods throughout the city. In early June, the French and Belgian consuls of Damascus reported news of decisive Christian victories and the arrival of Druze reinforcements from the Hauran and Damascus. Soon after, the stories were replaced by more accurate reports of decisive Druze victories and massacres against the Christians.[46] The news and rumors heightened existing inter-communal tensions between Muslims and Christians in Damascus.[47] Local Christians and European consuls feared Druze and Muslim plots against the Christian community, while local Muslims feared plots by the European powers, particularly France and Russia, and their perceived local sympathizers.[48] The local Christian chronicler Mikhail Mishaqah expressed surprise at Muslim panic about the local Christians due to the significant military advantage of the local Muslims and Ottoman authorities against the local Christians, who were largely unarmed.[48] Rumors spread in the Christian community, including one in which the Druze requested the Ottoman governor of Damascus, Ahmad Pasha, to hand over 72 Christians who were wanted by the Druze.[46] A related rumor among the Muslims held that 72 Christian notables had signed a petition calling for a Christian king to rule Zahle and Mount Lebanon. Other rumors circulating among the Muslim community regarded alleged Christian attacks on mosques.[48]

When the war spread to the Beqaa Valley, which was geographically closer to Damascus, a number of Damascenes volunteered or were dispatched to the battlefronts, including Muslims from the Salihiya quarter who marched towards Zahle.[48] Muslims and Druze throughout Syria celebrated the fall of Zahle, a town viewed by many Damascene Muslims as "insolent and ambitious", according to the historian Leila Tarazi Fawaz.[33] Fawaz asserts that the Damascene Muslims' rejoicing at the fall of Zahle stemmed from what they believed was the end of Zahle's threats to the interests of Damascene grain and livestock merchants. Mishaqah wrote that the extent of the celebrations would lead one to believe that "the [Ottoman] Empire conquered Russia".[49]

Most Damascenes were not directly involved in the civil war in Mount Lebanon, but tensions in Damascus were raised by the arrival of Christian refugees.[48] The war had precipitated an influx of Christian refugees to Damascus, mostly women and children and smaller numbers of adult males, from Hasbaya and Rashaya. Many Christians living in towns between Damascus and Mount Lebanon, such as Zabadani, also fled to Damascus due to the potential threat of attack by Druze forces.[48] By the end of June, estimates of Christian refugees in Damascus ranged from 3,000 to 6,000, most of them Greek Orthodox.[50] In addition to the refugees, large numbers of Christian peasants from Mount Hermon, who had traveled to work in the agricultural plains around Damascus and in the Hauran, were unable to return due to the threat of violence and were stranded in Damascus. The influx of refugees and peasants caused overcrowding in the city, particularly in the Christian quarter, which had a demoralizing effect on the Damascene Christians.[51]

Damascene Christians, many of them poor, helped care for the new arrivals, and much of the efforts to aid the refugees came from the city's Greek Orthodox and Melkite churches, but also from large contributions from some Muslim notables, including Muhammad Agha Nimr, Abd Agha al-Tinawi, Muhammad Qatana, al-Sayyid Hasan and Abd al-Qadir al-Jaza'iri; the latter was an Algerian Sufi cleric who had previously led resistance against the French conquest of Algeria. Aid for the refugees was insufficient and most did not have shelter, sleeping in alleys between the churches and in stables.[51] Although Muslim notables contributed aid to the refugees, the latter were seen as a threat by some Damascene Muslims, according to Fawaz. There was a high incidence of random and hostile acts against Christians, particularly refugees, by Muslims. Violence became more common between June and early July, after news of Druze victories in Rashaya, Hasbaya and Zahle. According to Mishaqah, the anger towards the refugees by "ignorant" Damascene Druze and Muslims grew in the aftermath of the Druze victories.[51]

Attempts to defuse tensions

editMuslim notables, such as Mahmud Effendi Hamza and Ahmad Hasibi, attempted to stop celebrations of Zahle's fall because it contributed to local Muslim-Christian tensions, but were unsuccessful. Hamza also attempted to mediate between the Druze and Christians in Zahle.[52] The Muslim notable who organized the most concerted effort to reduce tensions was Abd al-Qadir. Using his status as a hero of Muslim resistance against the French in Algeria, he commenced diplomatic efforts and met with nearly every leader of the Muslim community in Damascus and its environs, from ulema (scholars), aghas (local paramilitary commanders) and mukhtars (village headmen). He also met regularly with the French consul in Damascus, Michel Lanusse, and persuaded him to fund efforts to arm about 1,000 of his men, mostly Algerians, whom he tasked with defending the local Christians. On 19 June he began efforts to set up the defense of the Christian quarter in case of attack, but while he attempted to secretly prepare the defenses, local residents were likely aware of his activities.[53]

Ahmad Pasha, the governor of Damascus, assigned more guards to the Christian quarter in early June and prohibited weapons sales to the Druze and Christian belligerents in Mount Lebanon. European consuls requested that he help bring Christian survivors of the massacres in Hasbaya and Rashaya to Damascus and to reinforce the Ottoman garrisons in the Beqaa Valley. The European consuls also tasked Yorgaki, the vice-consul of Greece and a Turkish-speaker, with conveying their concerns to him about the danger posed to Christians amid the hostile environment in the city.[53] The most alarmed European consul was Lanusse, who firmly believed there was a great danger posed to the Christians and "predicted the worst", according to Fawaz.[49] His concerns were generally not shared by the other European consuls. In the opinion of the British consul, James Brant, while there were acts of hostility, verbal abuse and ill-treatment of Christians, there was "no fear" of Muslims harming Christians in the city, particularly if the Ottoman authorities intervened.[49] Brant and the other consuls were generally content with Ahmad Pasha's repeated reassurances that the situation in Damascus was under control. In early July, Ahmad Pasha had 14 cannons installed at the Citadel of Damascus and a cannon installed at the gate of the Umayyad Mosque and other mosques during Friday prayer as a means of deterrence.[54]

Local Christian fears of attack increased during the celebrations of Zahle's fall, and the tension became more acute in late June as the four-day Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha approached. Many Christians stayed home during this time and avoided visits to public places, relinquished rights to monetary debts owed them by Muslims and did not attend their jobs during the Eid festivities, bringing the local government to a standstill as most government clerks in the city were Christians. Eid passed without incident, and Abd al-Qadir received assurances from all the local Muslim leaders that they would keep order in the city, and Muslim notables, such as Mustafa Bey al-Hawasili, personally guaranteed the safety of Christians in meetings with the notables of the Christian quarters, including Hanna Frayj, Antun Shami and Mitri Shalhub. As a result, a sense of calm was restored for eight days and Christians returned to their shops, professions, and schools by 9 July.[55]

Massacre

editFirst day

editOn 8 July or 9 July, a group of Muslim boys, some the sons of Muslim notables, vandalized Christian property or otherwise targeted Christians, such as marking Christian houses, hanging crosses around the neck of dogs and tying crosses to their tails, and drawing crosses on the ground throughout the city's neighborhoods to make it inevitable that Christian pedestrians would step on their religious symbols. Frayj, Shami and Shalhub complained to Ahmad Pasha about the incidents, prompting the latter to seek out the boys and publicly punish them. A few were arrested, shackled and sent to the Christian quarter with brooms to sweep the streets.[56] As the boys were led to the Christian quarter, Muslim onlookers inquired about the situation and Abd al-Karim al-Samman, a brother of one of the arrested boys, yelled at the Ottoman guards to release the boys, and proceeded to chase after them with a stick. Al-Samman, who was thereafter known as al-sha'al (the fire starter),[56] was joined by his kinsmen, neighbors, friends and passersby, who beat the guards and released the boys. Al-Samman then urged the crowd to revolt and mete out vengeance on the Christians.[57]

Following al-Samman's speech, the occupants of the shops around the Umayyad Mosque formed a mob and headed for the Christian quarter yelling out anti-Christian slogans. A captain of local irregulars, Salim Agha al-Mahayani, may have led the initial crowds to the Christian quarter. News of the events spread throughout the city and its suburbs, and crowds from Midan, Salihiya, Shaghour, and Jaramana marched towards the Christian quarters. The crowds, estimated at 20,000 to 50,000 (these figures were likely smaller than the crowds' actual size), were made up of Muslim and Druze peasants, Kurdish irregulars, and ruffians from the city quarters.[57] They were largely armed with sticks and clubs, although a few carried axes, pistols or muskets. The overwhelming majority of Christians in the city were unarmed, with the exception of a few pistols.[58]

The gates of the Aqsab Mosque leading to the Christian quarter were broken down by Kurdish irregulars from Salihiya, and as the mob approached the quarter, its Ottoman guards were ordered to fire into the crowds and to fire cannon shells into the air by their commander, Salih Zaki Bey Miralay. Two rioters were killed or wounded and the crowds briefly dispersed. However, some rioters set alight the roof of a Greek Orthodox church and the local bazaar, and the ensuing flames prompted others to follow and set alight homes in the quarter.[58] By mid-day, Miralay and his soldiers were ordered to withdraw from their positions. Ottoman officers began to lose control of their soldiers, some of whom joined or led the rioters. The Kurdish irregulars of Muhammad Sa'id Agha Shamdin began to kill, rape and loot in the Christian quarter. Al-Hawasili attempted to intervene and hold back the crowds, but his soldiers abandoned him and joined in the riots. Besides al-Hawasili's failed attempt, no Ottoman military or political official attempted a significant intervention in the first few days of the riots.[59]

Although the mob targeted several different areas at the same,[59] in general, the first homes to be targeted were those of the wealthier Christians, followed by the neighboring Christian homes. Typically, the rioters broke down the homes' doors, attacked the men with their various weapons, and looted anything of value, stripping houses of windows, doors, paneling, and floor tiles. Women and children were threatened if they would not inform the mob about the whereabouts of the household's adult men or hidden jewelry, and occasionally girls and young women were abducted. After a particular house was plundered, it would be set alight. Irregular troops took the lead and priority in the plunder and they were followed by others in the mob. After the homes were burned, the Greek Orthodox, Melkite and Armenian churches were looted. At some point, a hospice for lepers was burned down with its residents inside.[60] Christians hiding in cellars, rooftops, and latrines in the quarter were mostly found and attacked by the mobs, but most of those who hid in wells evaded detection and were rescued by Abd al-Qadir's men.[61] Among the Christians who fled the city, a number were confronted by peasants and either killed or forced to convert to Islam. A large number of Christians from Bab Sharqi joined the metropolitan of the Syriac Catholics and found safety in the Greek Orthodox monastery of Saidnaya, a Christian village some 25 km from the Christian quarter.[62]

Foreign consulates were also assaulted, with the Russian consulate plundered and burned and its dragoman, Khalil Shehadi, killed. The Russians were especially targeted likely due to resentment against them stemming from the Crimean War between Russia and the Ottomans four years before. Afterwards, the French consulate, which the rioters held in particular disdain, was burned down, followed by the Dutch, Austrian and Belgian consulates.[60] The American vice-consul and Dutch consul narrowly escaped the mobs.[63] The only two foreign consulates not targeted during the massacre were the English and Prussian consulates.[64] The Russian and Greek consuls and the French consulate's staff had taken refuge in Abd al-Qadir's residence. Abd al-Qadir had been in a meeting with Druze elders in the village of Ashrafiya, some three to four hours' distance from Damascus, when the riots began.[65] Abd al-Qadir's men evacuated the French Lazarist missionaries from their monastery, as well as the French Sisters of Charity with one-hundred fifty children under their care.[66]

Second day

editAs most property had been looted and several hundred homes burned down during the first day, there was little property left to plunder on the following day. The rioters proceeded to loot Christian shops throughout the city's major bazaars. The Christians who remained in the quarter were largely in hiding for fear of attack.[62] On the first day, Abd al-Qadir's men had attempted three times to escort the Spanish Franciscans of Terra Santa to safety, but the Franciscans and a number of their acquaintances did not heed their calls; they were all killed on the second day and their convent was looted and burned.[66] A brief lull in the violence began to set in during the first night and the second day.[62]

Third day

editOn 11 July, the violence was renewed after rumors had spread that Christians had shot at a group of Muslims attempting to put out a fire that threatened to spread to the home of a Muslim religious sheikh, Abdallah al-Halabi. The Christians had been hired and armed by al-Halabi to guard his home from rioters and mistakenly shot at the group of Muslim fire extinguishers, believing them to be rioters. Some of the Muslims were wounded and the Christian shooters were killed. The incident raised the intensity of the riots, according to Brant, who wrote that any Christian who was encountered by the mob was killed. Kurdish irregulars and local Muslims attempted to storm the home of Abd al-Qadir, where numerous Christians were being sheltered, but Abd al-Qadir emerged from the home with his men and threatened to fire up on them. The crowds subsequently moved on to several other Muslim homes where Christians were being hidden and the homeowners were threatened to hand over the Christians, hundreds of whom were seized and executed.[62]

Last five days

editThe intensity of the killing and looting began to slow down on 12 July and tapered off completely by the 17 July.[67] During those last five days, rioters looted the few remaining objects in the ruined buildings of the Christian quarters, including doors, wood, and marble pieces. The only Christian-owned property untouched during the riots were in the caravanserais of the city's souks (market places).[67]

Aftermath

editInternational reactions

editThe 1860 Damascus Massacre was followed by a period of international tensions. Reports of the riots had made the international media, which led to international outrage.[68] The French sent six thousand soldiers to the Levant in order to protect the Syrian Christians and increase their own power in the region.[69] The British sent an investigative team, led by Lord Dufferin, in order to investigate the massacres and prevention of possible repetitions.[70] This forced the Ottomans to take action in order to show the European powers that they were capable of protecting their own minorities. This was necessary so that the Europeans would not use this insurrection as a way to enlarge their power within the Ottoman Empire.[71][72] The Ottomans sent Fuad Pasha to the region in order to restore order and fend off the European powers.[73][74] This tactic worked as Fuad Pasha's swift reaction to the violence conveyed the message that the Ottomans did not need the help of the French or any other European nation.[73]

Local impact

editAfter the riots, the Christian quarter of Damascus was completely destroyed. All inhabitants had either died or fled from the violence towards the city's citadel.[75] The atmosphere in the city remained tense for weeks after the riots and even after most of the Christian inhabitants had fled to Beirut.[76] Fuad Pasha, after arriving in the city, immediately decided to punish the Druzes for the committed violence in the hopes of restoring order to the city.[77] He quickly had 110 Druze men executed for their role in the riots. The regime of punishment held on for weeks after the riots, until late August.[78] The swift punishment by Fuad Pasha ensured that he was praised even by his harshest European critics for his role in the restoration of order in Damascus.[79] The year after the riots the Ottoman government tried to compensate the victims of the riots. An unexpected consequence of the riots was the increase in historical documentation about Damascus and the violence. To the residents of Damascus, the violence made such an impact that they started documenting the violence en masse. Mostly Christian, but some Muslim, accounts survived the war. Mikhail Mishaqa wrote his account of the events, which eventually resulted in him writing a historical work on Syria in the 18th and 19th century.[80] He had experienced the violence himself as he was attacked by an angry mob.[81]

Incidents elsewhere in Syria

editThe war in Mount Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley caused inter-communal tension throughout Ottoman Syria.[82] On 23 June, a Sunni Muslim man had been killed during a dispute with a Christian refugee in Beirut. The man's death prompted his angry relatives to demand from the Ottoman authorities that the perpetrator be executed. The authorities arrested a suspect and tried him immediately, but by then mobs were forming throughout the city, whose population had doubled due to the influx of Christian refugees. Panic ensued among the Christians in Beirut, and many were assaulted or threatened, including Europeans. The acting governor of Beirut, Isma'il Pasha, deployed troops throughout the city to prevent violence, but ultimately decided that the only way to disperse the mobs was by executing the Christian suspect,[82] who consistently declared his innocence. Although only the actual governor, Khurshid Pasha (who was in Deir al-Qamar), could sanction an execution and the European consuls refused to give their blessing to it, Isma'il Pasha had the suspect executed within twelve hours of the Muslim man's killing to avert further violence. The angry crowds consequently dispersed and calm was restored to Beirut.[83]

Tensions were also raised in other coastal cities, such as Tripoli, Sidon, Tyre, Acre, Haifa, and Jaffa, but their proximity to European warships in the Mediterranean helped maintain calm. Nonetheless, Tyre and Sidon were at the brink of civil strife due to violence between Sunni and Shia residents on the one side and Christian refugees fleeing the war on the other. Hundreds of Christians opted to leave Syria altogether, boarding ships to Malta or Alexandria.[83]

In the Galilee, peace was maintained by local Bedouin chieftains,[83] such as Aqil Agha, who assured Christians in Nazareth and Acre of his protection.[84] However, in the village of Kafr Bir'im near Safad, three Christians were killed by Druze and Shia Muslim raiders, while the mixed village of al-Bassa was also plundered.[85] A violent incident occurred between a Muslim and Christian man in Bethlehem, ending with the latter being beaten and imprisoned.[83] The authorities strengthened security and maintained calm in Jerusalem and Nablus.[85] The authorities also maintained calm in Homs, Hama, Latakia and Aleppo by introducing additional security measures. In the latter city, the Ottoman governor Umar Pasha appeared keen to maintain order, but his garrison was too small to ensure security in the city. Instead, many Christians pooled money together to pay for protection by local Muslims, who formed an ad hoc police force.[85]

International intervention

editThe bloody events led France to intervene and stop the massacre after Ottoman troops had been aiding local Druze and Muslim forces by either direct support or by disarming Christian forces. France, led by Napoleon III, recalled its ancient role as protector of Christians in the Ottoman Empire which was established in a treaty in 1523.[86] Following the massacres and an international outcry, the Ottoman Empire agreed on 3 August 1860 to the dispatch of up to 12,000 European soldiers to reestablish order.[87] This agreement was further formalized in a convention on 5 September 1860 with Austria, Great Britain, France, Prussia and Russia.[87] France was to supply half of that number, and other countries were to send supplementary forces as needed.[87]

General Beaufort d'Hautpoul was put in charge of the expeditionary force.[88] D'Hautpoul had experience and knowledge of the Middle East, as he had served during the 1830s as chief of staff for Ibrahim Pasha in the Egyptian campaigns in Southern Syria.[89] The French expeditionary corps of 6,000 soldiers, mainly from Châlons-sur-Marne, landed in Beirut on 16 August 1860.[89]

D'Hautpoul had instructions to collaborate with the Ottoman authorities in reestablishing order, and especially to maintain contact with the Ottoman minister Fuad Pasha.[89] Although the troubles had already been quelled by the Ottomans, the French expeditionary corps remained in Syria from August 1860 to June 1861,[87] longer than the initially agreed period of six months.[88] This prolonged French presence in Syria was soon objected to by the British government, which argued that pacification should be left to Ottoman authorities.[90]

An important consequence of the French expedition was the establishment of the autonomy of the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate from Ottoman Syria, with the nomination by the Sultan of an Armenian Christian governor from Constantinople, Daud Pasha, on 9 June 1861.

In a study of 2002, the French intervention was described as one of the first humanitarian interventions.[87]

Chronology

edit| Mount Lebanon (27 May – 20 June) | |

| 27 May | Outbreak of the war; 250 Maronite militias from Keserwan led by Taniyus Shahin went to collect the silk harvest from Naccache, but instead of returning to Keserwan, proceeded to Baabda in the al-Sahil district near Beirut, which the Druze saw as provocation. |

| 29 May | Keserwani Maronites raided the mixed villages of Qarnayel, Btekhnay and Salima and forced out its Druze residents. Druze assault against the mixed village of Beit Mery on the same day. |

| 30 May | Keserwani Maronite militiamen attempted to renew their assault against Beit Mery, but were countered by 1,800-2,000 Druze militiamen led by the Talhuq and Abu Nakad clans on the way. On the same day, a 200-strong Druze force led by Ali ibn Khattar Imad confronted 400 local Christian fighters at the village of Dahr al-Baidar in the area of Zahle. Ali Imad's force retreated to Ain Dara and Ali Imad died of his wounds on 3 June. |

| 31 May | In the renewed battle of Beit Mery, the 200-strong Maronite force was routed and forced to retreat to Brummana. By the day's end, the Druze fighters were in complete control of Metn, and between 35 and 40 Maronite majority villages were set alight and some 600 Maronites in the district slain. |

| 2 June | Bashir's forces, numbering some 3,000 Druze fighters, launched an assault on Deir al-Qamar and another assault the next day. The Druze managed to raze the town's outskirts which put up stiff resistance. |

| 3 June | After eight hours of the Druze assault, Deir al-Qamar surrendered on, partially as a result of internal divisions among the town's Christian militia. Casualties numbered 70 to 100 slain Druze and 17 to 25 Christians. The Druze plundered Deir al-Qamar until 6 June and destroyed 130 houses. |

| 4 June | A much larger Druze force defeated the Christians in Hasbaya after an hour-long assault and the Christian forces fled. |

| 11 June | A 5,000-strong Druze force assembled outside Rashaya consisting of local Druze militiamen under the command of Isma'il al-Atrash. |

| 18 June | Druze forces under Khattar Imad's command and reinforced by Shia peasants and Sunni Sardiyah Bedouin cavalry from Hauran (3,000 men altogether) began their assault on Zahle. The Druze stormed the town and within hours, Zahle was under Druze control. The Christians suffered between 40 and 900 casualties, while the Druze and their allies suffered between 100 and 1,500 casualties. |

| 20 June | The Druze successfully renewed their assault against Deir al-Qamar and captured the town. Between 1,200 and 2,200 Christians had been killed in the onslaught and many more had fled. |

| Damascus (9 July – 17 July) | |

| 9 July | A group of Muslim boys, some the sons of Muslim notables, vandalized Christian property or otherwise targeted Christians, such as marking Christian houses and drawing crosses on the ground throughout the city's neighborhoods. |

| 10 July | As most property had been looted and several hundred homes burned down during the first day, there was little property left to plunder on the following day. The rioters proceeded to loot Christian shops throughout the city's major bazaars. The Christians who remained in the quarter were largely in hiding for fear of attack. |

| 11 July | The violence was renewed after rumors had spread that Christians had shot at a group of Muslims attempting to put out a fire that threatened to spread to the home of a Muslim religious sheikh, Abdallah al-Halabi. |

| 12–17 July | During these last five days, rioters looted the few remaining objects in the ruined buildings of the Christian quarters, including doors, wood, and marble pieces. |

| 3 August | The Ottoman Empire agreed on 3 August 1860 to the dispatch of up to 12,000 European soldiers to reestablish order. |

| 16 August | The French expeditionary corps of 6,000 soldiers, mainly from Châlons-sur-Marne, landed in Beirut. |

See also

edit- Massacre of Aleppo (1850) perpetrated by Muslims against Christians

- List of conflicts in the Near East

- History of Lebanon

- 1843 and 1846 massacres in Hakkari perpetrated by Kurdish emirs against Assyrian Christians

- Late Ottoman genocides

- Martyrs of Damascus

References

edit- ^ a b c Fawaz, 1994, p. 226.

- ^ Fawaz, Leila Tarazi (1995). Occasion for War: Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860 (illustrated ed.). I.B.Tauris & Company. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-86064-028-5.

- ^ "Lebanon - Religious Conflicts". 2016-11-03. Archived from the original on 2016-11-03. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ^ "The Civil War in Syria". The New York Times. 21 July 1860. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ a b Hobby (1985). Near East/South Asia Report. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. p. 53.

the Druze and the Christians in the Shouf Mountains in the past lived in complete harmony..

- ^ Hazran, Yusri (2013). The Druze Community and the Lebanese State: Between Confrontation and Reconciliation. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 9781317931737.

the Druze had been able to live in harmony with the Christian

- ^ Artzi, Pinḥas (1984). Confrontation and Coexistence. Bar-Ilan University Press. p. 166. ISBN 9789652260499.

.. Europeans who visited the area during this period related that the Druze "love the Christians more than the other believers," and that they "hate the Turks, the Muslims and the Arabs [Bedouin] with an intense hatred.

- ^ CHURCHILL (1862). The Druzes and the Maronites. Montserrat Abbey Library. p. 25.

..the Druzes and Christians lived together in the most perfect harmony and good-will..

- ^ Khairallah, Shereen (1996). The Sisters of Men: Lebanese Women in History. Institute for Women Studies in the Arab World. p. 83.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris 2012, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d e Lutsky, Vladimir Borisovich (1969). "Modern History of the Arab Countries". Progress Publishers. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- ^ An Interview with Cheikh Malek el-Khazen. CatholicAnalysis.org. Published: 28 July 2014.

- ^ a b Fawaz, 1994, p. 47.

- ^ Fawaz, 1994, p. 48.

- ^ Fawaz, 1994, p. 49

- ^ a b c Fawaz, 1994, p. 50.

- ^ a b Fawaz, 1994, p. 54.

- ^ Farah, p. 560.

- ^ a b c Fawaz, 1994, p. 51.

- ^ a b Fawaz, 1994, p. 52.

- ^ Farah, Caesar E. The politics of interventionism in Ottoman Lebanon, 1830–1861, p. 564. I.B.Tauris, 2000. ISBN 1-86064-056-7.

- ^ a b Fawaz, 1994, p. 57.

- ^ a b c Fawaz, 1994, p. 58.

- ^ Harris 2012, pp. 157–158.

- ^ a b Fawaz, 1994, p. 59.

- ^ Fawaz, 1994, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d Fawaz, 1994, p. 62.

- ^ a b Fawaz, 1994, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Fawaz, 1994, p. 64.

- ^ a b Fawaz, 1994, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Fawaz, 1994, p. 66.

- ^ a b c Fawaz, 1994, p. 67.

- ^ a b c Fawaz, 1994, p. 68.

- ^ a b Fawaz, 1994, p. 69.

- ^ Fawaz, 1994, p. 70.

- ^ Fawaz, 1994, p. 71.

- ^ Fawaz, 1994, p. 72.

- ^ a b Fawaz, 1994, p. 73.

- ^ a b Mallat, p. 247.

- ^ Fawaz, 1994, p. 74.

- ^ a b (2002) "The Massacres of 1840 - 1860". Archived from the original on July 26, 2002. Retrieved 2013-08-17., http://www.tanbourit.com

- ^ Shaw, Ezel Kural. History of the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, 1977

- ^ "طوشة النصارى". www.sasapost.com. Retrieved 2023-06-12.

- ^ "ما هي خفايا "طوشة النصارى"؟ – شبكة جيرون الإعلامية" (in Arabic). Retrieved 2023-06-12.

- ^ "The 1860 Riot in Damascus", Muslim-Christian Relations in Damascus amid the 1860 Riot, BRILL, 2022-01-18, retrieved 2023-06-12

- ^ a b Fawaz, p. 78.

- ^ Fawaz, pp. 78-79.

- ^ a b c d e f Fawaz, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Fawaz, p. 81.

- ^ Fawaz, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b c Fawaz, p. 80.

- ^ Fawaz, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Fawaz, p. 82.

- ^ Fawaz, p. 83.

- ^ Fawaz, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Fawaz, p. 84.

- ^ a b Fawaz, p. 85.

- ^ a b Fawaz, p. 87.

- ^ a b Fawaz, p. 88.

- ^ a b Fawaz, p. 89.

- ^ Fawaz, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c d Fawaz, p. 92.

- ^ "What happened to Mr Cutsi? The Curious 'Murder' of the Dutch Consul in Damascus". securing-europe.nl. 16 March 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Fawaz, p. 90.

- ^ Fawaz, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Fawaz, p. 91.

- ^ a b Fawaz, p. 93.

- ^ "The Syrian Outbreak". The New York Times. August 13, 1860. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ Rogan, Eugene (October 2004). "Sectarianism and Social Conflict in Damascus: The 1860 Events Reconsidered". Arabica. 51 (4): 494. doi:10.1163/1570058042342207 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "The Massacres in Syria". Hansard. 20 August 1860. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ Rogan, Eugene (Oct 2004). "Sectarianism and Social Conflict in Damascus: The 1860 Events Reconsidered". Arabica. 51 (4): 494. doi:10.1163/1570058042342207 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Fawaz, Leila (1995). An Occasion for War - Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-520-08782-8.

- ^ a b Fawaz, Leila (1995). An Occasion for War - Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. California: University of California Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-520-08782-8.

- ^ "Ottoman Rule Restored". Britannica. Archived from the original on 2015-07-17. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ Fawaz, Leila (1995). An Occasion for War - Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. California: University of California Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-520-08782-8.

- ^ Fawaz, Leila (1995). An Occasion for War - Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. California: University of California Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-520-08782-8.

- ^ Fawaz, Leila (1995). An Occasion for War - Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. California: University of California Press. p. 139. ISBN 0-520-08782-8.

- ^ Fawaz, Leila (1995). An Occasion for War - Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. California: University of California Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-520-08782-8.

- ^ Fawaz, Leila (1995). An Occasion for War - Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. California: University of California Press. p. 163. ISBN 0-520-08782-8.

- ^ Rogan, Eugene (Oct 2004). "Sectarianism and Social Conflict in Damascus: The 1860 Events Reconsidered". Arabica. 51 (4): 495. doi:10.1163/1570058042342207 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Ozavci, Ozan (16 March 2018). "What happened to Mr Cutsi? The Curious 'Murder' of the Dutch Consul in Damascus". Archived from the original on 2020-03-07.

- ^ a b Fawaz, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Fawaz, 1994, p. 76.

- ^ Mansour, 2004, p. 262.

- ^ a b c Fawaz, 1994, p. 77.

- ^ Priestley, H.I.; American Historical Association (1938). France Overseas: A Study Of Modern Imperialism, 1938. Octagon Books. p. 87. ISBN 9780714610245. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ^ a b c d e Chesterman, S. (2002). Just War Or Just Peace?: Humanitarian Intervention and International Law. Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780199257997. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ^ a b Abkarius, I.I. (2010). The Lebanon in Turmoil - Syria and the Powers in 1860 - Book of the Marvels of the Time Concerning the Massacres in the Arab Country. Read Books Design. p. 35. ISBN 9781444696134. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ^ a b c Fawaz, 1994, p. 114.

- ^ Churchill, C.H. (1999). The Druzes and the Maronites under the Turkish Rule from 1840 To 1860. Adegi Graphics LLC. p. 251. ISBN 9781402196898. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

Bibliography

edit- Farah, Caesar E.; Centre for Lebanese Studies (Great Britain) (2000). Politics of Interventionism in Ottoman Lebanon, 1830-1861. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781860640568.

- Fawaz, L.T. (1994). An Occasion for War: Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520087828. Retrieved 2015-04-16.