The Dark Crystal is a 1982 dark fantasy film directed by Jim Henson and Frank Oz. It stars the voices of Stephen Garlick, Lisa Maxwell, Billie Whitelaw, Percy Edwards, and Barry Dennen. The film was produced by ITC Entertainment and The Jim Henson Company and distributed by Universal Pictures. The plot revolves around Jen and Kira, two Gelflings on a quest to restore balance to the world of Thra and overthrow the evil, ruling Skeksis by restoring a powerful broken Crystal.

| The Dark Crystal | |

|---|---|

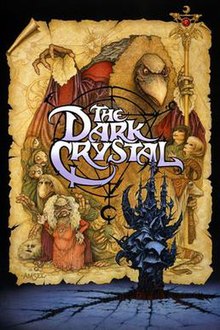

Theatrical release poster by Richard Amsel | |

| Directed by | |

| Screenplay by | David Odell |

| Story by | Jim Henson |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Oswald Morris |

| Edited by | Ralph Kemplen |

| Music by | Trevor Jones |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 93 minutes[3] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[4] or £25 million[5] |

| Box office | $41.4 million[6] |

It was marketed as a family film, but was notably darker than the creators' previous material. The animatronics used in the film were considered groundbreaking for the time, with most creatures, like the Gelflings, requiring around four puppeteers to achieve full manipulation. The primary concept artist was fantasy illustrator Brian Froud, famous for his distinctive fairy and dwarf designs. Froud also collaborated with Henson on the 1986 fantasy film Labyrinth.

The Dark Crystal was produced by Gary Kurtz, while the screenplay was written by David Odell, with whom Henson previously worked as a staff writer for The Muppet Show. The film score was composed by Trevor Jones. The film initially received mixed reviews from mainstream critics; while being criticized for its darker, more dramatic tone in contrast to Henson's previous works, it was praised for its narrative, aesthetic, and characters. Over the years, it has been re-evaluated by critics and has garnered a cult following.[7]

An Emmy Award-winning prequel television series, The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance, premiered on Netflix in 2019 and lasted for one season.

Plot

editOn a blighted planet a thousand years earlier, a powerful crystal cracked and two new races appeared: the cruel Skeksis, who use the crystal's power to extend their lives, and gentle Mystics, the urRu,[b] who dwell in a secluded valley. Among the Mystics is Jen, a young Gelfling adopted after the Skeksis slaughtered his clan. As the Great Conjunction of the world's three suns draws near, the dying Mystic Master instructs Jen to fulfill a prophecy to heal the crystal by first retrieving a missing shard from Aughra. If Jen fails to complete his quest before the three suns meet, the Skeksis will rule forever. The Master then dies, and the Skeksis Emperor dies at the same moment. The Skeksis General successfully challenges the Chamberlain for succession in a "trial by stone" and banishes him from the castle. When the Skeksis learn of Jen's existence, they send their army of giant crab-like Garthim to capture him, with the cunning Chamberlain following.

Jen meets Aughra and enters her orrery. Offered several shards, he chooses one that responds when he plays the Mystics' chord on his flute. Before Aughra can explain Jen's mission, the Garthim arrive and destroy the orrery, taking Aughra prisoner as Jen flees. Hearing the call of the crystal, the Mystics leave their valley and journey to the castle. On his journey through a forest swamp, Jen meets Kira, another Gelfling. The two learn more about each other when they accidentally "dreamfast", sharing each other's memories. They stay for a night with the Podlings who raised Kira, only for them and Kira's pet Fizzgig to flee when the Garthim raid the village. They are nearly caught, but the Chamberlain orders the Garthim back.

Jen and Kira discover a ruined Gelfling city where a prophecy is inscribed:

"When single shines the triple sun,

What was sundered and undone

Shall be whole, the two made one

By Gelfling hand or else by none."

Jen realizes that he must take the shard to the castle. The Chamberlain approaches and begs them to come to the castle with him. The Gelflings flee and reach the castle on Landstriders, intercepting the Garthim that raided Kira's village. They attack to free the Podlings but are cornered. Kira grabs Jen and Fizzgig and reveals wings that she uses to glide into the castle's dry moat. They enter the castle through the catacombs while above the Skeksis Scientist uses the crystal's rays to extract vital essence from Podlings. The Emperor drinks the essence and finds that it has only temporary restorative effects. The Chamberlain tries again to seize the Gelflings, and Jen stabs his hand with the shard; elsewhere the Mystic Chanter notices a wound on his hand. Enraged, the Chamberlain buries Jen in a cave-in and takes Kira as a gift to the Emperor. The Emperor reinstates him and orders Kira drained of essence. Aughra, imprisoned in the laboratory, tells Kira to call the captive animals for help. They break free and attack the Scientist, who deflects the draining prism before falling into the fiery crystal shaft; on a rocky plain, the Mystic Alchemist vanishes in flames. Aughra frees herself while Jen, awakened by Kira's call, climbs up the shaft to the laboratory.

The Gelflings make their way to a hall overlooking the crystal chamber, where the Skeksis gather for the conjunction ceremony. When the Skeksis spot them and order the Garthim to attack, Jen leaps onto the crystal but drops the shard. Kira glides down to the chamber, grabs the shard and throws it to Jen before the High Priest stabs her fatally. As the suns align Jen plunges the shard into the crystal, producing a force that throws him aside. The Garthim disintegrate and the drained Podlings regain their vitality while the dark stone covering the castle crumbles to reveal a crystalline structure. The Mystics arrive and use the crystal's light to draw the Skeksis to themselves, merging into angelic urSkeks. The urSkek leader tells Jen that they shattered the crystal a thousand years ago, sundering themselves and upsetting the world's balance. They revive Kira in gratitude and ascend toward the suns, leaving the crystal to light the rejuvenated world.

Cast

editMain

edit- Stephen Garlick as Jen, a Gelfling raised by the Mystics and entrusted to restore the Dark Crystal. He is performed by Jim Henson and doubled by Kiran Shah.

- Lisa Maxwell as Kira, a Gelfling raised by the Podlings who joins Jen's quest. She is performed by Kathryn Mullen and doubled by Kiran Shah.

- Billie Whitelaw as Aughra: The Keeper of Secrets and an astronomer. She is performed by Frank Oz and doubled by Kiran Shah and Mike Edmonds.

Skeksis

edit- Barry Dennen as the Chamberlain: A conniving official who covets the throne, performed by Frank Oz.

- Michael Kilgarriff as the General: The easily-angered Garthim-Master who becomes the new Emperor, performed by Dave Goelz.

- Jerry Nelson as the High Priest: A ritual master, performed by Jim Henson.

- Nelson and Henson also voiced and performed the Skeksis Emperor who dies at the beginning of the film.

- Steve Whitmire as the Scientist: A researcher of the crystal's power and ways to exploit the world's creatures.

- Thick Wilson as the Gourmand: The organizer of banquets, performed by Louise Gold.

- Brian Muehl as the Ornamentalist: The designer of garments and decor.

- John Baddeley as the Scroll Keeper: The castle historian, performed by Bob Payne.

- David Buck as the Slave-Master: Overseer of the drained Podlings, performed by Mike Quinn.

- Charles Collingwood as the Treasurer: A soft-spoken Skeksis who keeps the castle's riches, performed by Tim Rose.

urRu / Mystics

edit- Seán Barrett as urZah the Ritual-Guardian, performed by Brian Muehl.

- Muehl also performs the Master

- David Greenaway as the Healer, performed by Richard Slaughter.

- Jean Pierre Amiel as the Weaver

- Hugh Spight as the Cook

- Robby Barnett as the Numerologist

- Swee Lim as the Herbalist

- Simon Williamson as the Chanter, counterpart of the Chamberlain

- Hus Levant as the Scribe

- Toby Philpott as the Alchemist, counterpart of the Scientist

Others

edit- Percy Edwards as Fizzgig: a dog-like animal that is Kira's pet, performed by Dave Goelz.

- Joseph O'Conor as the urSkek leader, and the Narrator.

- Hugh Spight, Swee Lim, and Robbie Barnett as the Landstriders.

- Miki Iveria, Patrick Monckton, Sue Weatherby, and Barry Dennen as the voices of the Podlings/Pod People.

Production

editDevelopment

editThe spiritual kernel of The Dark Crystal is heavily influenced by Seth. I've always felt that the idea of perfect beings split into a good mystic part and an evil materialistic part which are reunited after a long separation is Jim's response to the teachings of that book. Jim admitted that he didn't understand the book himself, and that everyone would understand it—or not understand it—in their own way. But he thought it opened up a whole different way of looking at reality, which I think was one of his goals in the making of The Dark Crystal.

— Screenwriter David Odell[8]

Henson's inspiration for the visual aspects of the film came around 1975–76,[9] after he saw an illustration by Leonard B. Lubin in a 1975 edition of Lewis Carroll's poetry showing crocodiles living in a palace and wearing elaborate robes and jewelry.[8][10][11] The film's conceptual roots lay in Henson's short-lived The Land of Gorch, which also took place in an alien world with no human characters.[10] According to co-director Frank Oz, Henson's intention was to "get back to the darkness of the original Grimms' Fairy Tales", as he believed that it was unhealthy for children to never be afraid.[12]

Henson formulated his ideas into a 25-page story he entitled The Crystal, which he wrote whilst snowed in at an airport hotel.[8] Henson's original concept was set in a world called Mithra, a wooded land with talking mountains, walking boulders and animal-plant hybrids. The original plot involved a malevolent race called the Reptus group, which took power in a coup against the peaceful Eunaze, led by Malcolm the Wise. The last survivor of the Eunaze was Malcolm's son Brian, who was adopted by the Bada, Mithra's mystical wizards.[13]

This draft contained elements in the final product, including the three races, the two funerals, the quest, a female secondary character, the Crystal, and the reunification of the two races during the Great Conjunction. "Mithra" was later abbreviated to "Thra", due to similarities the original name had with an ancient Persian deity.[8] The character Kira was also at that point called Dee.[11]

Most of the philosophical undertones of the film were inspired by Jane Roberts's "Seth Material". Henson kept multiple copies of the book Seth Speaks, and insisted that Froud and screenwriter David Odell read it prior to collaborating for the film. Odell later wrote that Aughra's line "He could be anywhere then," upon being told by Jen that his Master was dead, could not have been written without having first read Roberts' material.[8]

The Bada were renamed "Ooo-urrrs", which Henson would pronounce "very slowly and with a deep resonant voice." Odell simplified the spelling to urRu, though they were ultimately named Mystics in the theatrical cut. The word "Skeksis" was initially meant to be the plural, with "Skesis" being singular, though this was dropped early in the filming process. Originally, Henson wanted the Skeksis to speak their own constructed language, with the dialogue subtitled in English.[8]

Accounts differ as to who constructed the language, and on what it was based. Gary Kurtz stated that the Skeksis language was conceived by author Alan Garner, who based it on Ancient Egyptian,[14] while Odell stated it was he who created it, and that it was formed from Indo-European roots. This idea was dropped after test screening audiences found the captions too distracting, but the original effect can be observed in selected scenes on the various DVD releases.[8] The language of the Podlings was based on Serbo-Croatian, with Kurtz noting that audience members fluent in Polish, Russian and other Slavic languages could understand individual words, but not whole sentences.[14]

The film was shot at Elstree Studios from April–September 1981, and exterior scenes were shot in the Scottish Highlands; Gordale Scar, North Yorkshire, England; and Twycross, Leicestershire, England. Once filming was completed, the film's release was delayed after Lew Grade sold ITC Entertainment to Robert Holmes à Court, who was skeptical of the film's potential, due to the bad reactions at the preview and the need to re-voice the film's soundtrack. The film was afforded minimal advertisement and release until Henson bought it from Holmes à Court and funded its release with his own money.[8]

Design

editBrian Froud was chosen as concept artist after Henson saw one of his paintings in the book Once upon a time.[11] The characters in the film are elaborate puppets, and none are based on humans or any other specific Earth creature. Before its release, The Dark Crystal was billed as the first live-action film without any humans on screen, and "a showcase for cutting-edge animatronics".[15]

The hands and facial features of the ground-breaking animatronic puppets in the film were controlled with relatively primitive rods and cables, although radio control later took over many of the subtler movements.[16] Human performers inside the puppets supplied basic movement for the larger creatures, which in some cases was dangerous or exhausting; for example, the Garthim costumes were so heavy (approx. 70 pounds) that the performers had to be hung up on a rack every few minutes to rest while still inside the costumes.[17] Swiss mime Jean-Pierre Amiel led a team of dancers, acrobats and others in performing the Mystics,[18] with Amiel himself performing the Weaver Mystic. Both Jen's dying Mystic master and the Ritual Guardian were performed by Brian Muehl, a recurring puppeteer on Sesame Street at the time, and many of the other Mystic performers would go on to work on the Star Wars film Return of the Jedi, as would two of the Skeksis' puppeteers, Mike Quinn (Slave Master) and Tim Rose (Treasurer).

When conceptualizing the Skeksis, Henson had in mind the seven deadly sins, though because there were ten Skeksis, some sins had to be invented or used twice.[18] Froud originally designed them to resemble deep sea fish,[19] but later designed them as "part reptile, part predatory bird, part dragon", with an emphasis on giving them a "penetrating stare."[18] Each Skeksis was conceived as having a different "job" or function, thus each puppet was draped in multicolored robes meant to reflect their personalities and thought processes.[19]

Each Skeksis suit required a main performer (from Jim Henson's main team of puppeteers, most of whom had previously worked on The Muppet Show), whose arm would be extended over his or her head in order to operate the creature's facial movements, while the other arm operated its left hand. Another performer would operate the Skeksis' right arm. A team of four technicians operated the Skeksis' hand and face animatronics. The Skeksis performers compensated for their lack of vision by having a monitor tied to their chests.[20] The Chamberlain Skeksis, in particular, was built with 21 electronic components.

In designing the Mystics, Froud portrayed them as being more connected to the natural world than their Skeksis counterparts. Henson intended to convey the idea that they were purged of all materialistic urges, yet were incapable of acting in the real world. Froud also incorporated geometric symbolism throughout the film in order to hint at the implied unity of the two races.[19] The Mystics were the hardest creatures to perform, as the actors had to walk on their haunches with their right arm extended forward, with the full weight of the head on it. Henson stated that he could hold a position in a Mystic costume for only 5–10 seconds.[18]

The Gelflings were designed and sculpted by Wendy Midener. They were difficult to perform, as they were meant to be the most human creatures in the film, and thus their movements, particularly their gait, had to be as realistic as possible. During scenes when the Gelflings' legs were off-camera, the performers walked on their knees in order to make the character's movements more lifelike.[20] According to Odell, the character Jen was Henson's way of projecting himself into the film.[19] Jen was originally meant to be blue, in homage to the Hindu deity Rama, but this idea was scrapped early on.[10]

Aughra was originally envisioned as a "busy, curious little creature" called Habeetabat, though the name was rejected by Froud, who found the name too similar to Habitat, a retailer he despised. The character was re-envisioned as a seer or prophetess, and renamed Aughra. In selecting a voice actor for Aughra, Henson was inspired by Zero Mostel's performance as a "kind of insane bird trying to overcome Tourettes syndrome" on Watership Down. Although the character was originally voiced by Oz, Henson wanted a female voice, and subsequently selected Billie Whitelaw.[8]

The character Fizzgig was invented by Oz, who wanted a character who served the same function as the Muppet poodle Foo-Foo, feeling that, like Miss Piggy, the character Kira needed an outlet for her caring, nurturing side.[8] The character's design was meant to convey the idea of a "boyfriend-repellant", to contrast the popular idea that it is easier to form a bond with a member of the opposite sex with the assistance of a cute dog.[19]

The Podlings were envisioned as people in complete harmony with their natural surroundings, thus Froud based their design on that of potatoes.[18] Their village was modeled on the Henson family home.[19]

In designing the Garthim, Froud took inspiration from the discarded carapaces of his and Henson's lobster dinners.[11][19] The Garthim were first designed three years into the making of the film, and were made largely of fiberglass. Each costume weighed around 70 lbs (32 kg), thus Garthim performers still in costume had to frequently be suspended on racks in order to recuperate.[18]

The Dark Crystal was the last film in which cinematographer Oswald Morris, BSC, involved himself in before retiring. He shot all the footage with a "light flex", a unit placed in front of the camera which gave a faint color tint to each scene in order to give the film a more fairy tale atmosphere similar to Froud's original paintings.[18]

Music

editThe film's soundtrack was composed by Trevor Jones, who became involved before shooting had started.[21] Jones initially wanted to compose a score which reflected the settings' oddness by using acoustical instruments, electronics and building structures. This was scrapped in favor of an orchestral score performed by the London Symphony Orchestra once Gary Kurtz became involved, as it was felt that an unusual score would alienate audiences. The main theme of the film is a composite of the Skeksis' and Mystics' themes.[22] Jones wrote the baby Landstrider theme in honor of his newly born daughter.[23]

Release

editBox office

editThe Dark Crystal was released in 858 theaters in North America on December 17, 1982 and finished third for the weekend with a gross of $4,657,335, behind Tootsie and The Toy, performing better than some people expected.[24] In its initial weekends, it had a limited appeal with some audiences for various reasons, including parental concerns about its dark nature when contrasted with Henson's family-friendly Muppet franchise.[25] In its third weekend, it moved up to second place nationally with a gross of $5,405,071 from 1,052 screens.[26] It made $40,577,001 in its box office run, managing to turn a profit. The film became the 16th highest-grossing film of 1982 within North America.[27] To date, it technically remains as one of the highest-grossing puppet animated films of all time, particularly for its domestic gross.[citation needed]

It made £2.4 million in the UK.[28]

Reception

editThe film received a mixed response upon its original release, but has earned a more positive reception in later years, becoming a favorite with fans of Henson and fantasy.[29] Vincent Canby of The New York Times negatively reviewed the film, describing it as a "watered down J. R. R. Tolkien... without charm as well as interest."[30] Kevin Thomas gave it a more positive assessment in the Los Angeles Times: "Unlike many screen fantasies, The Dark Crystal casts its spell from its very first frames and proceeds so briskly that it's over before you realize it. You're left with the feeling that you have just awakened from a dream."[31] Richard Corliss of Time magazine wrote: "The invention is impressive, but there is little indication of the Henson-Oz trademark: a sense of giddy fun. Audiences nourished on the sophisticated child's play of the Sesame Street Muppets and the music-hall camaraderie of The Muppet Show may not be ready to relinquish pleasure for awe as they enter The Dark Crystal's palatial cavern."[32] Variety praised the film as "a dazzling technological and artistic achievement ...that could teach a lesson in morality to youngsters at the same time it is entertaining their parents."[33]

Gary Arnold of The Washington Post wrote the main characters were "the softest and potentially weakest figures" in the film, but nevertheless, "The Dark Crystal leaves no doubt that Jim Henson and his colleagues have reached a point where they can create and sustain a powerfully enchanting form of cinematic fantasy."[34] Gene Siskel of The Chicago Tribune awarded the film 2+1⁄2 out of four stars in which he felt "...the resultant absence of dramatic tension cripples 'Crystal,' which doesn't have much going for it save for weird characters, who look like they just walked in from the bar scene in Star Wars. In fact, a lot of this movie looks like it was ripped off from Star Wars."[35] Colin Greenland, reviewing for Imagine magazine, stated that "The Dark Crystal is a technical masterpiece with splendid special effects work by a team two dozen strong. It may be that they did well to keep the story simple and then lavish a wealth of detail on it, rather than go for a more complicated fantasy and fail."[36]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 78% based on 50 reviews, with an average rating of 6.6/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "The Dark Crystal's narrative never quite lives up to the movie's visual splendor, but it remains an admirably inventive and uniquely intense entry in the Jim Henson canon."[37] On Metacritic it has a weighted average score of 66 out of 100 based on reviews from 13 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[38]

In 2008, the American Film Institute nominated this film for its Top 10 Fantasy Films list.[39]

Awards and nominations

edit| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | BAFTA Film Award | Best Special Visual Effects | Roy Field Brian Smithies Ian Wingrove |

Nominated | [40] |

| Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival | Grand Prize | Jim Henson Frank Oz |

Won | [41] | |

| Hugo Awards | Best Dramatic Presentation | Jim Henson Frank Oz Gary Kurtz David Odell |

Nominated | [42] | |

| Saturn Awards | Best Fantasy Film | Won | [43][44] | ||

| Best Special Effects | Roy Field Brian Smithies |

Nominated | [43] | ||

| Best Poster Art | Richard Amsel | Nominated | |||

| 2008 | Best DVD Classic Film Release | Nominated | [45] | ||

Home media

editThe Dark Crystal was first released on VHS, Betamax, and CED by Thorn EMI Video in 1983. The company's successor HBO Video re-released it on VHS in 1988 and also released it in widescreen on LaserDisc for the first time. On July 29, 1994, Jim Henson Video (through Disney's Buena Vista Home Video) re-released the film again on VHS and on a new widescreen LaserDisc. On October 5, 1999, Columbia TriStar Home Video and Jim Henson Home Entertainment gave the film one final VHS release and also released it on DVD for the first time and it has had multiple re-releases since including a Collector's Edition on November 25, 2003, and a 25th Anniversary Edition on August 14, 2007. It was also released on UMD Universal Media Disc for PlayStation Portable (PSP) on July 26, 2005. It was released on Blu-ray on September 29, 2009.

Another anniversary edition of The Dark Crystal was announced in December 2017, with a brand-new restoration from the original camera negative, and was released on Blu-ray and 4K Blu-ray on March 6, 2018.[46] Prior to the 4K/Blu-Ray release, Fathom Events presented the restored print of The Dark Crystal in US cinemas on February 25 and 28, and March 3 and 6, 2018.[47][48]

On January 1, 2024, a worldwide distribution agreement signed between Shout! Studios and the Jim Henson Company for The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth as well as associated content went into effect. The agreement grants Shout! Studios streaming, video-on-demand, broadcast, digital download, packaged media and limited non-theatrical rights to the films. The company released the films on all major digital entertainment platforms on February 6, 2024.[49]

Novelization

editA tie-in novelization of the film was written by A. C. H. Smith. Henson took a keen interest in the novelization, as he considered it a legitimate part of the film's world rather than just an advertisement. He originally asked Alan Garner to write it, but Garner declined on account of prior engagements. Henson and Smith met several times over meals to discuss the progress of the manuscript. According to Smith, their only major disagreement had arisen over his dislike of the Podlings, which he considered "boring". He included a scene in which a Garthim carrying a sackful of Podlings fell down a cliff and crushed them. Henson considered this scene to be an element of "gratuitous cruelty" that did not fit well into the scope of the story. In order to assist Smith in his visualizing the world of The Dark Crystal, Henson invited him to visit Elstree Studios during filming.[50] In June 2014, Archaia Entertainment reprinted the novelization, with included extras such as some of Brian Froud's illustrations and Jim Henson's notes.[51]

Cancelled sequel

editDuring the development phase of The Dark Crystal, director Jim Henson and writer David Odell discussed ideas for a possible sequel. Almost 25 years later, Odell and his wife Annette Duffy pieced together what Odell could recall from these discussions to draft a script for The Power of the Dark Crystal.[52] Genndy Tartakovsky was initially hired in January 2006 to direct and produce the film through The Orphanage animation studios in California.[53]

However, faced with considerable delays, the Jim Henson Company announced a number of significant changes in a May 2010 press release: It was going to partner with Australia-based Omnilab Media to produce the sequel, screenwriter Craig Pearce had reworked Odell and Duffy's script, and directing team Michael and Peter Spierig were replacing Tartakovsky. In addition, the film would be released in stereoscopic 3D.[54]

During a panel held at the Museum of the Moving Image on September 18, 2011, to commemorate the legacy of Jim Henson, his daughter Cheryl revealed that the project was yet again on hiatus.[55] By February 2012 Omnilab Media and the Spierig brothers had parted ways with the Henson Company due to budgetary concerns; production on the film has been suspended indefinitely.[56] In May 2014, Lisa Henson confirmed that the film was still in development, but it was not yet in pre-production.[57]

Ultimately, plans for a feature film were scrapped, and the unproduced screenplay was adapted into a 12-issue comic book series The Power of the Dark Crystal from Archaia Comics and BOOM! Studios, released in 2017.[58]

Spin-offs

editPrequel comics

editLegends of the Dark Crystal, an original English-language manga written by Barbara Kesel with art by Heidi Arnhold, Jessica Feinberg, and Max Kim, was published by Tokyopop. Its story is set hundreds of years before the events of The Dark Crystal, after the Great Conjunction which saw the splitting of the urSkeks into the Mystics and the Skeksis, but before the extermination of the Gelflings. The first volume of the series came out November 2007, followed sometime later by the second in August 2010. A third installment had been originally planned but was canceled and subsequently merged into the second volume.[59]

Another comic book prequel, The Dark Crystal: Creation Myths, was published by Archaia Entertainment as a series of three graphic novels.[60] The Henson Company and Archaia began collaborating on this project in late 2009.[61] A brief preview was made available on Free Comic Book Day in May 2011,[62] and the first installment was released January 2012, shortly thereafter spending two weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list of hardcover graphic books. In February 2013, the second installment was officially released. The third and final part was released in October 2015.

Prequel novels

editOn July 1, 2013, an announcement was made by The Jim Henson Company, in association with Grosset and Dunlap (a publishing division of Penguin Group USA) that they would be hosting a Dark Crystal Author Quest contest to write a new Dark Crystal novel, as a prequel to the original film. It would be set in the Dark Crystal world during a Gelfling Gathering. The winning author was J.M. (Joseph) Lee of Minneapolis, Minnesota, whose story, "The Ring of Dreams," was selected from almost 500 contest submissions.[63]

The novel series consists of four books: Shadows of the Dark Crystal, released on June 28, 2016; Song of the Dark Crystal, released July 18, 2017; Tides of the Dark Crystal, released December 24, 2018; and Flames of the Dark Crystal, released on August 27, 2019. Together, the novels serve to establish the setting of the Netflix series The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance, focusing on adventures of some of the series' side characters.

Prequel series

editIn May 2017, it was announced that The Jim Henson Company in association with Netflix would produce a prequel series titled The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance. Shooting began in the fall of 2017 with Louis Leterrier as director.[64] The prequel was written by Jeffrey Addiss, Will Matthews, and Javier Grillo-Marxuach.[65] The series premiered on August 30, 2019[66][7] and explores in ten episodes the world created for the original film.[65]

In other media

edit- A book entitled The World of The Dark Crystal, written and illustrated by Brian Froud, was released at the same time as the film. The book, written as the annotated translation of the Book of Aughra by fictional Oxford professor "J.J. Llewellyn", expands greatly on the world of "Thra", detailing its conditions and history, as well as providing some additional story background.

- An illustrated children's storybook version, The Tale of the Dark Crystal, written by Donna Bass and illustrated by Bruce McNally.

- A board game called The Dark Crystal Game was also released in 1982 by Milton Bradley.

- A book-and-cassette adaptation was released in 1983 by Disneyland Records as part of its Read-Along Adventures series.

- In 1983, a graphic adventure based on the film was released for the Apple II and Atari 8-bit computers.

- Marvel Comics published a comic book adaptation of the film by writer David Anthony Kraft and artists Bret Blevins, Vince Colletta, Rick Bryant, and Richard Howell in Marvel Super Special #24.[67][68]

- Vogue commissioned six of the film's costume designers to fashion clothes based on the characters of the film.[69]

- Music duo The Crystal Method used samples from the film in the song "Trip Like I Do", released on their 1997 album Vegas.

- In February 2011, Sandstorm Productions – a firm that partnered with various design studios to facilitate the development and distribution of board games and collectible card games – revealed that it had acquired the license to produce games based on various Henson properties, including The Dark Crystal.[70] Before any definitive plans were made, however, Sandstorm went out of business in June 2012.

- Archaia announced plans for a role-playing game based on The Dark Crystal at the August 2011 Gen Con gaming convention, intending to publish it later the following year. Like its Origins Award-winning Mouse Guard game, The Dark Crystal will be designed by Luke Crane and utilize mechanics similar to that of The Burning Wheel.[71][72] As of 2024 the game has not been released.

- In August 2013, Black Phoenix Alchemy Lab - a company that produces body and household blends with a dark, romantic Gothic tone - debuted the first of their licensed The Dark Crystal perfumes. The debut included four Skeksis blends: skekUng the Garthim-Master, skekNa the Slave-Master, skekTek the Scientist and skekZok the Ritual-Master.[73]

- In the Jim Henson's Creature Shop Challenge episode "Return of the Skeksis", the competing creature designers had to work in teams of three to build a Skeksis that has been banished to different parts of Thra and has been called back to the Skeksis Castle.

- The song "Return to Oz" by the band Scissor Sisters on the album Scissor Sisters (2004) features a reference to the film's antagonists the Skeksis: The Skeksis at the rave meant to hide deep inside their sunken faces and their wild, rolling eyes, But their callous words reveal that they can no longer feel.

- The song "Skeksis" on the album Alien by Canadian band Strapping Young Lad is named after the film's antagonists; the song itself contains an interpolation of the film's theme melody.[74] Singer-songwriter Devin Townsend would later base Ziltoid the Omniscient on the characters from the film.

- Dark Crystal Tales by Cory Godbey, a children's book of short stories, was released in August 2017.

- A book entitled The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance: Inside the Epic Return to Thra was released in November 2019, two months after the Netflix series premiered. It details the making of the series and features concept art, interviews, set photography, and more.

- In October 2020, a guide to the characters and creatures from the Dark Crystal universe called The Dark Crystal Bestiary: The Definitive Guide to the Creatures of Thra was released.

- In January 2021, the River Horse company has announced that it is developing a role-playing game set in the world of both the original film and the Netflix prequel series called The Dark Crystal Adventure Game that will be released in 2021.[75][76][77]

- In March 2021, it was announced that the Royal Opera House will adapt the film into a ballet entitled The Dark Crystal: Odyssey. It will be directed and choreographed by Wayne McGregor and is described as a "coming-of-age story" for family audiences.[78][79]

See also

edit- The Land of Gorch

- John Bauer (illustrator)— an inspiration for Brian Froud's work on The Dark Crystal

Notes

edit- ^ The film's distribution rights were purchased by The Jim Henson Company from ITC Entertainment in August 1984.[1] Currently, Universal Pictures handles theatrical distribution in the United States and internationally (including the United Kingdom[2]) due to prior contractual obligations with the former Associated Film Distribution and ITC, but the film's ownership and copyright are controlled by The Jim Henson Company.

- ^ The Mystics are called "urRu" once on-screen as they enter the crystal chamber.

References

edit- ^ Jay Jones, Brian (2013). "Chapter 12: Twists and Turns". Jim Henson: The Biography. Ballantine Books (Random House). pp. 374–375. ISBN 978-0345526113.

- ^ a b "The Dark Crystal". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ "The Dark Crystal (A)". British Board of Film Classification. November 3, 1982. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ "The Dark Crystal: The Ultimate Visual History" (September 19, 2017)

- ^ BRITISH PRODUCTION 1981 Moses, Antoinette. Sight and Sound; London Vol. 51, Iss. 4, (Fall 1982): 258.

- ^ "The Dark Crystal (1982)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ a b "Simon Pegg Says Watching the Original Dark Crystal Was an 'Overwhelming Experience'". People.com. August 20, 2019. Archived from the original on August 25, 2019. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j David Odell (2012), "Reflections on Making The Dark Crystal and Working with Jim Henson". In: Froud, B., Dysart, J., Sheikman, A. & John, L. The Dark Crystal: Creation Myths, Vol. II. Archaia. ISBN 978-1-936393-80-0

- ^ Fantastic Films Archived June 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine #32, February, 1983

- ^ a b c McAra, Catriona (2013) A Natural History of "The Dark Crystal": The Conceptual Design of Brian Froud. In: The Wider Worlds of Jim Henson. McFarland, Jefferson, pp. 101-116.

- ^ a b c d Brian Froud (2003), "A Journey into The Dark Crystal". In: Froud, B. & Llewellyn, J. J., The World of the Dark Crystal. Pavilion Books. ISBN 1-86205-624-2

- ^ Peter Hartlaub, Q&A: Frank Oz on Henson, “Dark Crystal” and the Kwik Way Archived May 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, SFGate, (Jun 28, 2007)

- ^ Jim Henson, The Mithra Treatment [DVD special Feature]. The Dark Crystal: Collector's Edition, Dir. Jim Henson & Frank Oz. 1982. Colombia Tristar Home Entertainment, 2003. DVD.

- ^ a b Hutchinson, David. "Producing the world of The Dark Crystal: A new direction for the man behind ‘Star Wars" and "Empire" Gary Kurtz". Starlog: The Magazine of the Future. 66 (January 1983):19-20.

- ^ Wright 2005.

- ^ Rickitt 2000, p. 225.

- ^ Bacon 1997, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e f g Making-of. The World of the Dark Crystal. Dir. Jim Henson & Frank Oz. 1982. Colombia Tristar Home Video, 1999. DVD.

- ^ a b c d e f g Making-of. Reflections of the Dark Crystal: Light on the Path of Creation. Dir. Michael Gillis. Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, 2007. DVD.

- ^ a b Making-of. Reflections of the Dark Crystal: Shard of Illusion. Dir. Michael Gillis. Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, 2007. DVD.

- ^ Hoover, Tom (2010). Soundtrack Nation: Interviews with Today's Top Professionals in Film, Videogame, and Television Scoring, 1st Ed. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781435457621.

- ^ Cinemascore 2011.

- ^ "The Dark Crystal" at Oscars Outdoors Archived September 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Oscars.org (September 4, 2012)

- ^ Ginsberg, Steven (December 21, 1982). "'Tootsie,' 'Toy' And 'Dark Crystal' Win Big At National Box-Office". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- ^ Scheib 2010.

- ^ "Box-Office Off To Running Start". Daily Variety. January 4, 1983. p. 1.

- ^ The Dark Crystal Summary Archived October 4, 2019, at the Wayback Machine at Box Office Mojo.

- ^ "Back to the Future: The Fall and Rise of the British Film Industry in the 1980s - An Information Briefing" (PDF). British Film Institute. 2005. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ Von Gunden 1989, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Canby 1982.

- ^ Thomas 1982.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (January 3, 1983). "Cinema: Magical, Mystical Muppet Tour". Time. p. 82. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "Film Reviews: The Dark Crystal". Variety. December 15, 1982. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (December 21, 1982). "The Finest in Fantasy". The Washington Post. p. C1. Archived from the original on November 3, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 20, 1982). "Lack of dramatic tension dooms Jim Henson's 'Dark Crystal'". The Chicago Tribune. Section 5, p. 4. Archived from the original on December 23, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Greenland, Colin (July 1983). "Film Review". Imagine. No. 4. p. 37.

- ^ "The Dark Crystal (1982)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ "The Dark Crystal". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "BAFTA Awards". Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "1/16/1983 – 'D.C. wins Fantasy Film at Avoriaz film festival.' Jim Henson's Red Book". January 16, 2012. Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "1983 Hugo Awards - The Hugo Awards". July 26, 2007. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "THE LATE LATE REVIEW: THE DARK CRYSTAL - TRASH". Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "Past Saturn Award Recipients". Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "Thoughts On The Film - The Dark Crystal Tribute". Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ^ "The Dark Crystal 4K Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ Scott, Ryan (December 12, 2017). "The Dark Crystal Returns to Theaters in February". Movieweb. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Simon. "Lisa Henson Talks 'The Dark Crystal' As The Classic Movie Returns To Theaters". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Grobar, Matt (January 4, 2024). "Shout! Studios Lands Exclusive Rights To 'Labyrinth,' 'The Dark Crystal' & Other Jim Henson Company Titles". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ "Jim Henson's Labyrinth – The 25th Anniversary Podcast with ACH Smith and Sam Downie – Sam Downie". Dsoundz.co.uk. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Jim Hensons Dark Crystal HC Novel @TFAW.com". Things From Another World. Archived from the original on December 7, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Carroll 2006.

- ^ The Jim Henson Company 2006.

- ^ The Jim Henson Company 2010.

- ^ Hill 2011.

- ^ Swift 2012.

- ^ Watkins, Gwynne (May 16, 2014). "Checking in on The Dark Crystal, Labyrinth, and Other Jim Henson Company Franchises". New York. New York Media LLC. Archived from the original on May 18, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (November 21, 2016). "'Dark Crystal' Sequel Finally Coming to Life Thanks to Comic Book Series". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ Arnhold 2010.

- ^ Archaia Entertainment 2011.

- ^ Warmoth 2010.

- ^ Diamond Comic Distributors 2010.

- ^ Lodge, Sally (July 8, 2014). "Penguin and Jim Henson Company Team Up for Dark Crystal Project". Publishers Weekly. publishersweekly.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ Petski, Denise (May 18, 2017). "'The Dark Crystal: Age Of Resistance': Jim Henson Prequel Series Set At Netflix". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ a b ""The Dark Crystal" prequel series coming to Netflix". Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ "The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance premiering on Netflix in August: See the exclusive images". Entertainment Weekly. May 21, 2019. Archived from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ "Marvel Super Special #24". Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Friedt, Stephan (July 2016). "Marvel at the Movies: The House of Ideas' Hollywood Adaptations of the 1970s and 1980s". Back Issue! (89). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 66–67.

- ^ Falk 2012, p. 141.

- ^ ICv2 February 1, 2011.

- ^ ICv2 August 24, 2011.

- ^ Richardson 2011.

- ^ "Security Check Required". Facebook.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "The 12 best Devin Townsend songs, by Devin Townsend". Teamrock.com. October 13, 2015. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Dark Crystal RPG Adventure In the Works From River Horse". 411MANIA. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ "The Dark Crystal is Getting a Tabletop RPG". Comicbook.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Gavin Sheehan (January 4, 2021). "River Horse Will Be Making A Tabletop RPG For The Dark Crystal". bleedingcool.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ "The Royal Opera House reveals highlights of its first full Season since 2019". Archived from the original on April 1, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "The Dark Crystal Will Return...as a Ballet". March 24, 2021. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

Bibliography

edit- "Jim Henson's The Dark Crystal". Archaia Titles. Hollywood, CA: Archaia Entertainment. July 11, 2011. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- Arnhold, H. (January 2, 2010). "Comment on 'Excitement Can Be Suffocating' by *HeidiArnhold". heidiarnhold.deviantart.com. Los Angeles, CA: deviantART. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- Bacon, M. (October 16, 1997). No Strings Attached: The Inside Story of Jim Henson's Creature Shop. New York City, NY: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-862008-4. [1] Archived September 4, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Canby, Vincent (December 17, 1982). "Review: Henson's Crystal". The New York Times. p. C10. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- Carroll, L. (October 4, 2006). "Dark Crystal Sequel Gives Jim Henson's Puppet Epic a Second Chance". MTV Movie News. New York City, NY: MTV Networks. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- Falk, K. (2012). Imagination Illustrated: The Jim Henson Journal. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1452105826.

- "An Interview with Trevor Jones". Cinemascore. Randall D. Larson. May 24, 2011. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- "Free Comic Book Day 2011 Gold Comic Books Announced". PREVIEWSworld. Timonium, MD: Diamond Comic Distributors. December 1, 2010. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- Henson, J. & Oz, F. (dir.); Henson, J., Kurtz, G. & Lazer, D. (prod.); Henson, J. & Odell, D. (writ.) (December 17, 1982). The Dark Crystal (Motion picture). New York City, NY: Jim Henson Productions.

- Hill, J. (October 12, 2011). "Jim Henson's Family and Fans Aim to Honor and Extend His Creative Legacy – Part 2". HuffPost Entertainment. New York City, NY: The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 14, 2011. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- "Sandstorm Nets Marvel, Henson Licenses". Madison, WI: ICv2. February 1, 2011. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- "Dark Crystal RPG from Archaia Entertainment". Madison, WI: ICv2. August 24, 2011. Archived from the original on December 18, 2011. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- "Genndy Tartakovsky to direct Power of the Dark Crystal" (PDF). Henson Media Relations: Press Releases. Hollywood, CA: The Jim Henson Company. February 1, 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "The Dark Crystal". Henson Productions: Fantasy & Sci Fi. Hollywood, CA: The Jim Henson Company. December 19, 2008. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- "Omnilab Media and The Jim Henson Company join forces to launch the Australian feature production of the highly anticipated Power of the Dark Crystal" (PDF). Henson Media Relations: Press Releases. Hollywood, CA: The Jim Henson Company. May 4, 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- User: J. Richardson (August 5, 2011). "Thread: The Dark Crystal RPG". RPGnet tabletop roleplaying forum. Berkeley, CA: Skotos Tech. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Rickitt, R. (October 1, 2000). Special Effects: The History and Technique. New York City, NY: Billboard Books. ISBN 978-0-8230-7733-5.

- Scheib, R. (May 2010). "Review: The Dark Crystal". Moria: The Science Fiction, Horror and Fantasy Film Review. Christchurch, NZ. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- Swift, B. (February 8, 2012). "The Dark Crystal Sequel, The Power of the Dark Crystal, on Hiatus". If Magazine. Glebe, NSW, Australia: The Intermedia Group. Archived from the original on February 12, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- Thomas, Kevin (December 17, 1982). "'Dark Crystal': A Jen-uine Triumph?". Los Angeles Times. p. K10. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Von Gunden, K. (January 7, 1989). "The Dark Crystal: Other Worlds, Other Times". Flights of Fancy: The Great Fantasy Films. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. pp. 30–44. ISBN 978-0-7864-1214-3. Archived from the original on July 4, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- Warmoth, B. (March 1, 2010). "Jim Henson Company Confirms Dark Crystal and Labyrinth Comics Following Fraggle Rock". MTV Splash Page. New York City, NY: MTV Networks. Archived from the original on November 5, 2011. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- Wright, A. (November 2005). Conrich, I.; Hammerton, J (eds.). "Selling the Fantastic: The marketing and merchandising of the British fairytale film in the 1980s". Journal of British Cinema and Television. 2 (2). Edinburgh, Scotland, UK: Edinburgh University Press: 256–274. doi:10.3366/JBCTV.2005.2.2.256. ISSN 1743-4521.

- Gaines, Caseen (2017). The Dark Crystal: The Ultimate Visual History. San Rafael, United States: Insight Editions. ISBN 978-1-60887-811-6.