Jeremy Strohmeyer (born October 11, 1978) is an American convicted murderer, serving four consecutive life terms for the sexual assault and murder of 7-year-old Sherrice Iverson (October 20, 1989 – May 25, 1997)[1] at Primadonna Resort and Casino in Primm, Nevada, on May 25, 1997.

Jeremy Strohmeyer | |

|---|---|

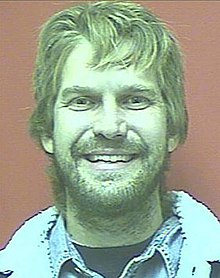

Strohmeyer in December 2008 | |

| Born | October 11, 1978 Long Beach, California, U.S. |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated |

| Conviction(s) | First degree murder First degree kidnapping Sexual assault of a child under the age of 16 with substantial bodily harm Sexual assault of a child under the age of 16 |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment without parole |

| Details | |

| Victims | Sherrice Iverson, 7 |

| Date | May 25, 1997 |

| Country | United States |

| Location(s) | Primm, Nevada |

| Imprisoned at | High Desert State Prison |

The case drew national attention by focusing on the safety of children in casinos and on the revelation that Strohmeyer's friend, David Cash Jr., said he saw the crime in progress but did not stop it.[2]

The crime

editIn the early morning of May 25, 1997, two males, Jeremy Strohmeyer (age 18) and David Cash Jr. (age 17), were at the Primadonna Resort & Casino at Primm, Nevada, near the California state line. The two young men had arrived at the gambling establishment, accompanied by Cash's father, from their homes in Long Beach. Strohmeyer was a student at Wilson High School in Long Beach.[3]

At around 4 a.m., Strohmeyer began repeatedly making apparently "playful" contact with 7-year-old Sherrice Iverson, who was roaming the casino alone. The young girl's father was gambling and drinking. Her father left Sherrice in the care of her 14-year-old brother, Harold, in the casino's arcade. This resulted in Sherrice running around unmonitored. The girl had been returned to her father several times through the night, having been found alone by security. Eventually, Strohmeyer followed Sherrice into a women's restroom.

While in the restroom, the two began throwing wet paper wads at one another. Sherrice then reportedly tossed a yellow plastic "Wet Floor" sign at Strohmeyer. At around this time, Strohmeyer's friend, David Cash, entered the restroom and witnessed Strohmeyer forcibly taking Iverson into a stall. When Cash looked in from the adjacent stall, he saw Strohmeyer holding his left hand over Iverson's mouth and fondling her with his right. After this, Cash left the restroom and was followed 20 minutes later by Strohmeyer, who confessed to him that he had killed the girl.[4]

Three days later, Strohmeyer was taken into custody at his home. Two classmates in Long Beach had identified him after security tape footage captured by cameras at the casino was released by Nevada police and played on the television news. Strohmeyer was charged with first-degree murder, first-degree kidnapping, and sexual assault of a minor. When questioned by police, Strohmeyer stated that he molested Iverson and strangled her to stifle her screams. Before leaving, Strohmeyer noticed Iverson was still alive and twisted her head in an attempt to break her neck. After hearing a loud popping sound, he rested her body in a sitting position on the toilet with her feet in the bowl. Strohmeyer's attorneys later tried to have the confession suppressed because he was not given legal counsel. However, the police claimed that Strohmeyer waived his right to have an attorney present during questioning.[4]

Plea bargain

editStrohmeyer's defense attorney was Leslie Abramson, who represented many high-profile clients, including the Menendez brothers. Strohmeyer claimed he was high on alcohol and drugs at the time and did not remember committing the crimes. It was even suggested that perhaps the witness, David Cash, had, in fact, been the one to murder Sherrice, as Strohmeyer claimed to have no recollection of his actions and the witness was the one to actually tell him what he had seen him doing in the bathroom that night. Abramson also noted that Strohmeyer's biological father is in prison and his biological mother is in a mental hospital.[2]

Strohmeyer's trial was scheduled to begin in September 1998. Strohmeyer was originally facing a possible death sentence for the murder (had the case gone to trial), but hours before his trial was to start, Abramson entered a plea bargain on his behalf. On September 8, 1998, Strohmeyer pleaded guilty to four charges: first-degree murder, first-degree kidnapping, sexual assault on a minor with substantial bodily harm and sexual assault on a minor. On October 14, 1998, he was sentenced to four life terms, one for each crime he pleaded guilty to, to be served consecutively without possibility of parole.[2][5]

After the trial

editImprisonment

editStrohmeyer was initially incarcerated at Ely State Prison, a maximum security prison located north of Ely, Nevada, where most prisoners in Nevada who are serving life without parole are imprisoned for at least the early portion of their sentences. He was placed in administrative segregation, meaning that he was not placed in the general inmate population, but rather in his own cell in a special secured section.[6] His prison number is #059389. Strohmeyer was reportedly transferred to the Lovelock Correctional Center in Lovelock, Nevada, where he is classified as "medium" custody. Strohmeyer as of January 2023 is in High Desert State Prison which is a low/medium custody.

Appeals

editJeremy Strohmeyer subsequently appealed his conviction.

In 2000, he was unsuccessfully defended by Camille Abate.[7] Strohmeyer recanted his confession and accused Abramson of lying to him and bullying him into pleading not guilty in order to cover up her misunderstanding of Nevada law. Strohmeyer's new attorneys also suggested that Abramson wanted him to plead guilty because Strohmeyer's parents could not afford to pay her additional fees if the case went to trial. Abramson denied all the allegations.[8] Ultimately, his appeal was rejected.

In 2001, the Nevada Supreme Court rejected an appeal by Strohmeyer to withdraw his guilty plea. In January 2006, Strohmeyer lost a federal court bid to review his case.[9]

On May 31, 2018, a request for parole was made based on 2012 and 2016 Supreme Court decisions that juveniles should have a chance at parole. [10] His request was denied in July 2018. [11]

Lawsuit by adoptive parents

editStrohmeyer's adoptive parents filed a $1 million lawsuit against Los Angeles County and its adoption workers in October 1999. They claimed that social workers deliberately withheld crucial information that would have stopped them from adopting him as an infant. Specifically, they claimed they were never told that Strohmeyer's biological mother had severe mental problems, including that she suffered from chronic schizophrenia and had been hospitalized more than 60 times prior to Strohmeyer's birth. The Strohmeyers, however, continued to support their son.[12]

The suit was dismissed in 2002 on the basis that it was barred by the statute of limitations, and the dismissal was affirmed on appeal.[13][14]

David Cash

editSherrice Iverson's mother demanded that David Cash Jr., also be charged as an accessory to murder, but authorities stated there was insufficient evidence connecting him to the actual crime, and Cash was never prosecuted for any offense related to the murder.

In the weeks following Strohmeyer's arrest, Cash told the Los Angeles Times that he did not dwell on the murder of Sherrice Iverson. "I'm not going to get upset over somebody else's life. I just worry about myself first. I'm not going to lose sleep over somebody else's problems." He also told the newspaper that the publicity surrounding the case had made it easier for him to "score with women." Cash also told the Long Beach Press-Telegram: "I'm no idiot ... I'll get my money out of this."[15][16]

Cash would be labeled "the bad Samaritan" and become the target of a campaign by students who attempted to get him kicked out of UC Berkeley for not stopping the crime. Two local Los Angeles radio hosts, Tim Conway Jr. and Doug Steckler, subsequently held a rally to have Cash expelled from the University of California at Berkeley, but University officials stated that they had no basis to remove him since he was not convicted of any crime.

Cash has never expressed remorse over Iverson's death. In a radio interview, he stated that "It was a very tragic event...The simple fact remains I don't know this little girl ... I don't know people in Panama or Africa who are killed every day, so I can't feel remorse for them. The only person I know is Jeremy Strohmeyer", but still insisted that he did nothing wrong.[4][17]

The Sherrice Iverson bill

editSherrice Iverson's murder led to the passage of Nevada State Assembly Bill 267, requiring people to report to authorities when they have reasonable suspicions that a child younger than 18 is being sexually abused or violently treated. The impetus for the bill stemmed from Cash's inaction during the commission of the crime.

The "Sherrice Iverson" bill, introduced by Nevada State Assembly Majority Leader Richard Perkins (D-Henderson), provides for a fine and possible jail time for anyone who fails to report a crime of the nature that led to the creation of the bill. The bill was enacted in 2000.[18]

Sherrice Iverson's murder also led to the passage of California Assembly Bill 1422, the Sherrice Iverson Child Victim Protection Act, which added section 152.3 to California's Penal Code.[19][20] This duty to rescue law requires that a person notify law enforcement if they witness a murder, rape, or any lewd or lascivious act, where the victim is under 14 years old.[20][21]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Michigan Daily, Berkeley wants student to get out of town, "The Michigan Daily Online". Archived from the original on May 13, 2007. Retrieved June 3, 2007.

- ^ a b c Teen pleads guilty in Nevada casino killing of girl, CNN.com, September 8, 1998. (retrieved on August 25, 2008). Archived February 20, 1999, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wride, Nancy (October 12, 1997). "Truth Stronger Than Friction". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 24, 2017. "While Wilson High classmate Jeremy Strohmeyer drew gasps of media attention in late May with his arrest on charges he raped and strangled a 7-year-old at a Nevada casino,[...]"

- ^ a b c Nevada v. Strohmeyer - "Casino Child Murder Trial", CourtTV (retrieved on August 25, 2008). Archived March 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Killer of Girl in Casino Gets Life Term, New York Times, October 15, 1998. (retrieved on August 25, 2008)

- ^ Strohmeyer taken to Ely prison, Associated Press (reprinted by Las Vegas RJ News), October 24, 1998 (retrieved on August 31, 2008). Archived October 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ LAS VEGAS RJ:NEWS: Justice unchanged for killer Archived May 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Abramson testifies she didn't force Strohmeyer to take plea by Harriet Ryan, Court TV Online, February 8, 2000. Retrieved on August 25, 2008 Archived March 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Confessed Casino Child Killer Loses Federal Appeal, Associated Press (reprinted by abc7.com), January 18, 2006 (retrieved on August 25, 2008).

- ^ "As a teen, he killed a little girl in a casino. Now he wants parole". June 2018.

- ^ "Judge denies new sentence for man who killed girl at Nevada casino". July 23, 2018.

- ^ Adoptive parents of convicted killer sue social workers by Jennifer Auther, CNN.com, October 27, 1999 (retrieved on August 25, 2008).

- ^ Hardesty, Greg (September 8, 2002). "Parents: We weren't told of child's condition". The Miami Herald. p. 13. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ Strohmeyer v. County of Los Angeles, unpublished opinion (California Court of Appeal 7 February 2002).

- ^ [1], The Michigan Daily, September 30, 1998 (retrieved on February 16, 2009) Archived May 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Who can possibly reach David Cash's heart of darkness?, San Francisco Chronicle, October 4, 1998 (retrieved on February 16, 2009) Archived August 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Protesters want student expelled Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Bruin, August 31, 1998 (retrieved on August 31, 2008)

- ^ "Archives". Los Angeles Times. September 19, 2000.

- ^ "Assembly Bill No. 1422" (PDF). California Legislative Information.

- ^ a b "California Penal Code Section 142-181". California Legislative Information. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015.

- ^ "California Penal Code Section 281-289.6". California Legislative Information. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016.