Robert F. Kennedy's Day of Affirmation Address (also known as the "Ripple of Hope" Speech[1]) is a speech given to National Union of South African Students members at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, on June 6, 1966, on the University's "Day of Reaffirmation of Academic and Human Freedom". Kennedy was at the time the junior U.S. senator from New York. His overall trip brought much US attention to Africa as a whole.

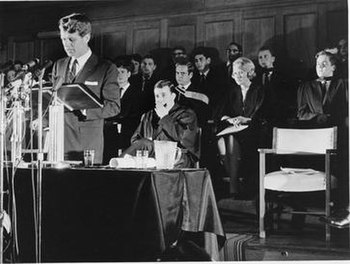

Robert Kennedy delivering his speech in Jameson Hall. To the right is the chair left empty to signify Ian Robertson's absence | |

| Date | June 6, 1966 |

|---|---|

| Duration | 33:52 minutes |

| Venue | Jameson Hall, University of Cape Town |

| Location | Cape Town, South Africa |

| Also known as | "Ripple of Hope" Speech |

| Theme | Apartheid/Civil rights/Activism |

In the address Kennedy talked about individual liberty, Apartheid, and the need for justice in the United States at a time when the American civil rights movement was ongoing. He emphasized inclusiveness and the importance of youth involvement in society. The speech shook up the political situation in South Africa and received praise in the media. It is often considered his greatest and most famous speech.

Background

editKennedy's decision to go to South Africa

editKennedy was first invited to give the address at the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS)'s annual "Day of Reaffirmation of Academic and Human Freedom"[2] in the autumn of 1965 by union president Ian Robertson. The "Day of Affirmation" (as it was known in short) was an assembly designed to directly oppose the South African government's policy of Apartheid. Robertson would later say that the idea for Kennedy to come speak came to him in the middle of the night. He had been looking for a foreign speaker, and he thought Kennedy "captured the idealism [and] the passion of young people all over the world."[3] Prominent New Hampshire conservative William Loeb III publicly denounced a potential visit to the country by Kennedy as making no more sense than letting "a viper into one's bed."[4] The South African government was hesitant to let Kennedy speak but eventually granted him a visa for fear of snubbing a future President of the United States.[5] By the time it arrived five months later, Kennedy had become involved in a political battle in New York. He told Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs J. Wayne Fredericks over the phone that he preferred to wait until after the November elections to travel. Fredericks replied "Go now. If you postpone, it will confirm the idea that that everything takes precedence over Africa." Kennedy called back 20 minutes later, resolved to carry forward with the trip.[4]

The decision was not without controversy. When Kennedy approached the South African Embassy for advice on his itinerary, Ambassador Harald Langmead Taylor Taswell informed him that he had nothing to say, that the South African government disapproved of NUSAS, and that no ministers would receive him. Two weeks before the scheduled trip, Ian Robertson was banned by the government from participating in social and political life for five years.[4] South Africa also denied visas to 40 news correspondents that were to cover the event. According to the Ministry of Information, South Africa did not want the visit "to be transformed into a publicity stunt...as a build-up for a future presidential election."[6]

Back in March, White House watchdog Marvin Watson notified President Lyndon B. Johnson of Kennedy's application for a visa and his plans to address student groups. With the help of White House Press Secretary Bill Moyers, the administration began crafting a "Johnson doctrine for Africa."[6] One week before Kennedy's departure, Johnson gave his only ever speech on Africa. The New York Times wrote, "Cynics will wonder if the attention given to Senator Kennedy's visit," did not explain Johnson's sudden desire to give attention to the continent.[4]

Arrival

editRobert Kennedy, his wife Ethel, his secretary Angie Novello, and speechwriter Adam Walinsky arrived at Jan Smuts airport in Johannesburg shortly before midnight on June 4. Between 1,500[4]-4,000[7] people had crowded the airport. Most were enthusiastic supporters, though some did protest Kennedy's arrival. Kennedy gave a brief speech in the "non-white" section of the terminal. After the crowd gave a rendition of "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow", Kennedy took the podium and thanked them for their welcome. He later talked about his decision to travel to South Africa and his intentions, saying, "I come here to hear from all segments of South African thought and opinion. I come here to learn what we can do together to meet the challenges of our time, to do as the Greeks once wrote: to tame the savageness of man, and make gentle the life of this world."[3]

Margaret H. Marshall, vice president of NUSAS, stood in for Ian Robertson to host Kennedy.[7] The next day Kennedy toured Pretoria. Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd declined to see him and restricted other government ministers from doing so. That evening Kennedy had dinner with South African businessmen, who expressed their confusion over the fact that their country was overlooked by the United States, despite being committed to anti-Communism. In response, Kennedy asked "What does it mean to be against Communism if one's own system denies the value of the individual and gives all power to the government - just as the Communists do?"[4]

On June 6, the day of the address, Kennedy met with Ian Robertson and presented him with a copy of John F. Kennedy's book, Profiles in Courage, signed by both himself and Jacqueline Kennedy.[8]

The address

editComposition

editIn preparation for the address Walinsky wrote a draft, but Kennedy was displeased with it. His advisers recommended that he turn to Allard K. Lowenstein for assistance on South Africa matters. Lowenstein initially declined to assist—he was about to escort the aging Norman Thomas to the Dominican Republic—but at the last minute he agreed to meet Kennedy.[9] Lowenstein bluntly criticized the draft, saying it practically expressed the white views of the South African government and "wasn't attentive to the struggles of the people."[7][9] He brought together a group of South African students who had been studying on the East Coast. They expressed similar opinions. The speech was changed accordingly with the help of Adam Walinksky and Richard Goodwin, taking a more hard-line stance against Apartheid.[7][9]

Delivery

editKennedy arrived at the University of Cape Town in the evening of June 6. A crowd of 18,000 white students and faculty had gathered to see him, and it took almost a half hour before he reached Jameson Hall. Speakers were set up so the crowd outside could listen.[3] In the hall were banners hung in protest of the Vietnam War. Kennedy followed a ceremonial procession into the hall led by a student carrying the extinguished "torch of academic freedom." On the dais near the podium a chair was symbolically left empty to signify Ian Robertson's absence.[10]

Summary

editKennedy's approach to talking to South Africans was the discourse of America's own history.[11] He opened the address by employing misdirection, one of his favorite oratorical devices:[7]

I come here this evening because of my deep interest and affection for a land settled by the Dutch in the mid-seventeenth century, then taken over by the British, and at last independent; a land in which the native inhabitants were at first subdued, but relations with whom remain a problem to this day; a land which defined itself on a hostile frontier; a land which has tamed rich natural resources through the energetic application of modern technology; a land which was once the importer of slaves, and now must struggle to wipe out the last traces of that former bondage. I refer, of course, to the United States of America.

This drew laughter and applause from the audience.[12] After thanking the student union for the invitation to speak, Kennedy discussed individual liberty, apartheid, communism, and the need for civil rights. He emphasizes inclusiveness, individual action,[13] and the importance of youth involvement in society.[14] At the climax, he lists four "dangers" that would obstruct the goals of civil rights, equality, and justice. The first is futility, "the belief there is nothing one man or one woman can do against the enormous array of the world's ills." Kennedy counters this idea, stating:

Yet many of the world's great movements, of thought and action, have flowed from the work of a single man. A young monk began the Protestant Reformation, a young general extended an empire from Macedonia to the borders of the earth, and a young woman reclaimed the territory of France. It was a young Italian explorer who discovered the New World, and 32 year old Thomas Jefferson who proclaimed that all men are created equal. "Give me a place to stand," said Archimedes, "and I will move the world." These men moved the world, and so can we all.

The notable phrase "ripple of hope" came shortly thereafter:

It is from numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped each time a man stands up for an ideal or acts to improve the lot of others or strikes out against injustice. He sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current that can sweep down the mightiest wall of oppression and resistance.

The second danger was expediency, the idea "that hopes and beliefs must bend before immediate necessities." Kennedy maintained, "that there is no basic inconsistency between ideals and realistic possibilities - no separation between the deepest desires of heart and of mind and the rational application of human effort to human problems." The third danger was timidity. He said, "Moral courage is a rarer commodity than bravery in battle or great intelligence. Yet it is the one essential, vital quality for those who seek to change the world which yields most painfully to change." The fourth and final danger, comfort, "the temptation to follow the easy and familiar path of personal ambition and financial success so grandly spread before those who have the privilege of an education." He said that the current generation could not accept comfort as an option:

[Comfort] is not the road history has marked out for us. There is a Chinese curse which says "May he live in interesting times." Like it or not, we live in interesting times. They are times of danger and uncertainty; but they are also the most creative of any time in the history of mankind. And everyone here will ultimately be judged - will ultimately judge himself - on the effort he has contributed to building a new world society and the extent to which his ideals and goals have shaped that effort.

Kennedy finished his speech by quoting John F. Kennedy's inaugural address:

"The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it - and the glow from that fire can truly light the world." [...] "With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth and lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God's work must truly be our own." I thank you.

Aftermath

editRemainder of trip

editThe last day of the trip took place in Johannesburg with numerous meetings and a Soweto tour. In the morning he met with Albert Lutuli, an anti-Apartheid activist that had been banned from political work and press coverage.[11] From the roof of his car in Soweto, Kennedy gave the crowd the first news they had heard of Lutuli in over five years.[7]

Return to America

editFollowing his trip to Africa, Kennedy wrote an article in Look magazine titled, "Suppose God is Black?" It was the first time in the United States a national politician condemned apartheid in a widely circulated publication.[11]

Legacy

editThe address is often considered Kennedy's greatest and most famous oration.[1][11][15] Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. called it "his greatest speech." Frank Taylor of the London Daily Telegraph "the most stirring and memorable address ever to come from a foreigner in South Africa."[4] Ian Robertson labeled it "the most important speech of Kennedy's life."[3] The address was inspirational for many anti-Apartheid activists, including the imprisoned Nelson Mandela.[16]

The phrase "ripple of hope" has become one of the most quoted phrases in American politics.[11] It is inscribed on Robert Kennedy's memorial in Arlington National Cemetery. Inside the library of the University of Virginia School of Law, there is a bust of Robert Kennedy (an alumnus) with an inscription from the ripple of hope speech.[17]

Senator Ted Kennedy, brought up the speech in his eulogy for Robert, saying "What he leaves to us is what he said, what he did, and what he stood for. A speech he made to the young people of South Africa on their Day of Affirmation in 1966 sums it up the best..."[18]

The first and final drafts of the speech are in Robert Kennedy's Senate papers, which are held by the John F. Kennedy Library.[19]

Citations

edit- ^ a b Memmott, Mark (30 June 2013). "LOOKING BACK: RFK's 'Ripple Of Hope' Speech In South Africa". npr.org. National Public Radio. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Byrd 1995, p. 713.

- ^ a b c d Larry Shore (producer) (2009). RFK in the Land of Apartheid (Television Production). Shoreline Productions.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schlesinger Jr., Aurther Meier (2002). Robert Kennedy and His Times. Vol. 2 (reprint ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 743, 744, 746. ISBN 9780618219285.

- ^ Weiss, Andrea (24 May 2016). "50th anniversary of Robert Kennedy's 'Ripple of Hope' speech". www.uct.ac.za. University of Cape Town. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ a b Shesol 1998, p. 300.

- ^ a b c d e f Tye, Larry (5 July 2016). Bobby Kennedy: The Making of a Liberal Icon. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 371–373, 375–376. ISBN 9780679645207.

- ^ Heuvel & Gwirtzman 1970, p. 155.

- ^ a b c Halberstam, David (5 March 2013). The Unfinished Odyssey of Robert Kennedy. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781480405899.

- ^ Kennedy, Kerry (6 June 2012). "Day of Affirmation: "Ripple of Hope"". Huffington Post. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Shore, Larry. "A Ripple of Hope: Background". www.rfksafilm.org/. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Williams 1997, p. xvii.

- ^ "Ripple of Hope: Teacher Resources". Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights. Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "RFK in Capetown". www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience. Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "RFK in the Land of Apartheid: A Ripple of Hope". pbs.org. Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Collins, Michael (12 June 2016). "Rep. Steve Cohen reflects on visit to South Africa". The Tennessean. Washington D.C. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ "University of Virginia News Story". 2016-08-24. Archived from the original on 2016-08-24. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ Kennedy, Edward M. (8 June 1968). "Address at the Public Memorial Service for Robert F. Kennedy". americanrhetoric.com. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Thomas 2013, p. 460.

References

edit- Byrd, Robert C. (1995). Senate, 1789-1989: Classic Speeches, 1830-1993. Vol. 3. U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160632570.

- Heuvel, William Jacobus Vanden; Gwirtzman, Milton (1970). On His Own: Robert F. Kennedy, 1964-1968. Doubleday.

- Shesol, Jeff (1998). Mutual Contempt: Lyndon Johnson, Robert Kennedy, and the Feud that Defined a Decade. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393345971.

- Thomas, Evan (2013). Robert Kennedy: His Life. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781476734569.

- Williams, John A. (1997). From the South African past: narratives, documents, and debates. Sources in modern history. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780669287899.

External links

edit- Text and audio of the speech from the John F. Kennedy Library