Westworld is a 1973 American science fiction Western film written and directed by Michael Crichton. The film follows guests visiting an interactive amusement park containing lifelike androids that unexpectedly begin to malfunction. The film stars Yul Brynner as an android in the amusement park, with Richard Benjamin and James Brolin as guests of the park.

| Westworld | |

|---|---|

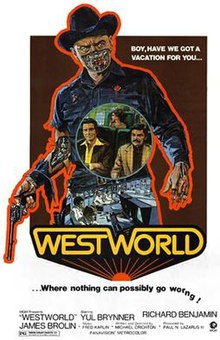

Theatrical release poster by Neal Adams | |

| Directed by | Michael Crichton |

| Written by | Michael Crichton |

| Produced by | Paul N. Lazarus III |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gene Polito |

| Edited by | David Bretherton |

| Music by | Fred Karlin |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.2 million[2] |

| Box office | $10 million[3] |

The film was from an original screenplay by Crichton and was his first theatrical film as director, after one TV film. It was also the first feature film to use digital image processing to pixellate photography to simulate an android point of view.[4] Critical reception was largely positive by contemporary and retrospective critics and Westworld was nominated for Hugo, Nebula, and Saturn awards.

Westworld was followed by a sequel, Futureworld (1976), and a short-lived television series, Beyond Westworld (1980). A television series based on the film debuted in 2016 on HBO.

Plot

editIn the near future, a highly realistic adult amusement park called Delos features three themed "worlds": Western World (the American Old West), Medieval World (medieval Europe) and Roman World (the ancient city of Pompeii). The resort's worlds are populated with lifelike androids that are practically indistinguishable from human beings, each programmed in character for their historical environment. For $1,000 per day, guests may indulge in any adventure with the android population of the park, including sexual encounters and simulated fights to the death.

Peter Martin, a first-time Delos visitor and his friend John Blane, on a repeat visit, go to Westworld. One of the attractions is the Gunslinger, an android programmed to instigate gunfights. The firearms issued to the park guests have temperature sensors that prevent them from shooting anything with a high body temperature, such as humans, but allow them to "kill" the cold-blooded androids. The Gunslinger's programming allows guests to draw their guns and kill it, with the android always returning the next day for another duel.

The technicians running Delos notice problems are beginning to spread: the androids in Roman World and Medieval World begin experiencing various breakdowns and systemic failures, which may have also spread to Westworld.

After a night spent having sex with two android prostitutes, John is accosted by the same gunslinger Peter killed in the saloon the previous day. Peter bursts into the room and once again shoots the gunslinger dead. Peter is jailed awaiting trial, so John breaks him out and the two try to head out of town.

The malfunctions become more serious when a robotic rattlesnake bites John and against its program, a female android refuses a guest's advances in Medieval World. The failures escalate until Medieval World's Black Knight android kills a guest in a sword fight. The resort's supervisors try to regain control by shutting down power to the park. The shutdown traps them in central control when the doors automatically lock, and they cannot turn the power back on to escape. The androids in all three worlds run amok, operating on reserve power.

Peter and John, recovering from a drunken bar-room brawl, wake up in Westworld's brothel, unaware of the park's breakdown. When the Gunslinger challenges the men to a showdown, John treats the confrontation as an amusement but the android shoots him dead. Peter runs for his life, and the android follows.

Peter flees to other areas of the park but finds only dead guests, damaged androids and a panicked technician attempting to escape Delos, who is soon killed by the Gunslinger. Peter climbs down through a manhole in Roman World into the underground control complex and discovers that the resort's computer technicians suffocated in the control room when the ventilation system shut down. The Gunslinger stalks him through the underground corridors. While running away, Peter enters an android-repair laboratory. When the Gunslinger arrives there, Peter pretends to be an android lying on a table for repairs before throwing acid into the Gunslinger's face. Peter flees, returning to the surface inside the Medieval World castle.

With its optical inputs damaged, the Gunslinger cannot track Peter visually and tries instead to find him using its infrared scanners. Peter stands beneath flaming torches and discovers that they mask his presence from the android. He sets it on fire with a torch and leaves the android to burn. Peter hears a call in a dungeon and finds a chained woman begging for help. He gives her water but this causes her to short-circuit and shut down, revealing her to be a robot. The burned shell of the Gunslinger attacks him once again before succumbing to its damage.

Peter then sits on the dungeon steps, exhausted and shocked, as the memory of Delos' marketing slogan resonates: "Boy, have we got a vacation for you!"

Cast

edit- Yul Brynner as the Gunslinger

- Richard Benjamin as Peter Martin

- James Brolin as John Blane

- Norman Bartold as Medieval Knight

- Alan Oppenheimer as the Chief Supervisor

- Victoria Shaw as the Medieval Queen

- Dick Van Patten as the Banker

- Linda Gaye Scott as Arlette, the French saloon prostitute

- Steve Franken as the Delos technician shot dead by the Gunslinger

- Michael Mikler as the Black Knight

- Terry Wilson as the Sheriff

- Majel Barrett as Miss Carrie, madame of the Westworld bordello

- Anne Randall as Daphne, the serving-maid who refuses a guest's advances in Medieval World

- Robert Hogan as Ed Wren (uncredited)

- Kenneth Washington as Technician (uncredited)

- Nora Marlowe as the Hostess

- Charles Seel as the Bellhop

- Robert Patten as the Technician

Production

editScreenplay

editCrichton said he did not wish to make his feature directorial debut (after one TV film – 1972's Pursuit) with science fiction but "That's the only way I could get the studio to let me direct. People think I'm good at it I guess."[3]

Crichton's agent introduced him to producer Paul N. Lazarus III; they became friends and decided to make a film together.[5] The script was written in August 1972. Lazarus said he asked Crichton why he did not tell the story as a book; Crichton said he felt the story was visual and would not really work as a book.[5]

The script was offered to all the major studios. They all turned down the project except for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, then under head of production Dan Melnick and president James T. Aubrey. Crichton said

MGM had a bad reputation among filmmakers; in recent years, directors as diverse as Robert Altman, Blake Edwards, Stanley Kubrick, Fred Zinneman and Sam Peckinpah had complained bitterly about their treatment there. There were too many stories of unreasonable pressure, arbitrary script changes, inadequate post production, and cavalier recutting of the final film. Nobody who had a choice made a picture at Metro, but then we didn't have a choice. Dan Melnick ... assured [us] ... that we would not be subjected to the usual MGM treatment. In large part, he made good on that promise.[6]

Crichton said pre-production was difficult. MGM demanded script changes up to the first day of shooting and the leads were not signed until 48 hours before shooting began. Crichton said he had no control over casting[3] and MGM originally would only make the film for under a million dollars but later increased this amount by $250,000.[2] Crichton said that $250,000 of the budget was paid to the cast, $400,000 to the crew, and the remainder on everything else (including $75,000 for sets).[7]

Principal photography

editThe film was shot in 30 days. To save time, Crichton tried to shoot only what was needed, with minimal takes.[8] Westworld was filmed in several locations, including the Mojave Desert, the gardens of the Harold Lloyd Estate, several MGM sound stages and on the MGM backlot, one of the final films to be shot there before the backlot was sold to real estate developers and demolished.[9] It was filmed with Panavision anamorphic lenses by Gene Polito.

Richard Benjamin later said he loved making the film:

It probably was the only way I was ever going to get into a Western, and certainly into a science-fiction Western.... So you get to do stuff that's like you're 12 years old. All of the reasons you went to the movies in the first place. You're out there firing a six-shooter, riding a horse, being chased by a gunman, and all of that. It's the best![10]

The Gunslinger's appearance is based on Chris Adams, Brynner's character from The Magnificent Seven. The two characters' costumes are nearly identical.[11] According to Lazarus, Yul Brynner agreed to play the role for only $75,000 ($393,000 in modern dollars[12]), because he needed the money.[5]

Crichton later wrote that "most of the situations in the film are cliches; they are incidents out of hundreds of old movies", so the scenes "should be shot as clichés. This dictated a conventional treatment in the choice of lenses and the staging".[13] The original script and original ending of the movie culminated in a fight between Martin and the Gunslinger, which resulted in the Gunslinger being torn apart by a rack. Crichton said he "had liked the idea of a complex machine being destroyed by a simple machine" but when attempting it, "it seemed stagey and foolish", so the idea was dropped.[14] He also wanted to open the film with shots of a hovercraft traveling over the desert but was unable to get the effect he wanted within a limited budget, so this was dropped as well.[14]

Score

editThe score for Westworld was composed by American composer Fred Karlin. It combines ersatz western scoring, source cues, and electronic music.[15]

Post-production

editIn the published screenplay, Crichton explained how he re-edited the first cut of the movie because he was depressed by how long and boring it was. Scenes that were deleted from the rough cut include a bank robbery and sales room sequences, an opening with a hovercraft flying above the desert, additional and longer dialogue scenes, more scenes with robots attacking and killing guests including a scene where one guest is tied down to a rack and is killed when his arms are pulled out, a longer chase scene with the Gunslinger chasing Peter and one where the Gunslinger cleans his face with water after Peter throws acid on him. Crichton's assembly cut featured a different ending that included a fight between the Gunslinger and Peter and an alternate death scene in which the Gunslinger was killed on a rack.[16] Once the film was completed on time, MGM authorized the shooting of some extra footage. A television commercial to open the film was added; because there was a writers' strike in Hollywood at the time, this was written by Steven Frankfurt, a New York advertising executive.[17]

Digital image processing

editWestworld was the first feature film to use digital image processing. Crichton originally went to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena but after learning that two minutes of animation would take nine months and cost $200,000, he contacted John Whitney Sr., who in turn recommended his son John Whitney Jr. The latter went to Information International, Inc., where they could work at night and complete the animation faster and cheaper.[18] Whitney Jr. digitally processed motion picture photography at Information International, Inc. to appear pixelized to portray the Gunslinger android's point of view.[4] The approximately 2 minutes and 31 seconds' worth of cinegraphic block portraiture was accomplished by color-separating (three basic color separations plus black mask) each frame of source 70 mm film images, scanning each of these elements to convert into rectangular blocks, then adding basic color according to the tone values developed.[19] The resulting coarse pixel matrix was output back to film.[20] The process was covered in the American Cinematographer article "Behind the scenes of Westworld" and in a 2013 New Yorker online article.[21][22]

Reception

editBox office

editThe film was released on an experimental regional saturation basis[23] and grossed $2 million in its first week in 275 theatres in the Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland areas.[24] It earned $4 million in rentals in the US and Canada by the end of 1973.[25] After a re-release in 1976, it earned $7,365,000.[26]

Book tie-in

editCrichton's original screenplay was released as a mass-market paperback in conjunction with the film.[27]

Critical response

editVariety described the film as excellent, saying that it "combines solid entertainment, chilling topicality, and superbly intelligent serio-comic story values".[23] Vincent Canby of the New York Times wrote that Crichton had made "a creditable debut as a film director", but "Crichton the director seems to have had more fun with the film than Crichton the writer, whose screenplay can offer us no better explanation for the sudden, bloody robot rebellion than an epidemic of 'central mechanism psychosis.'"[28] Gene Siskel gave the film three stars out of four, calling the first half "exciting and provocative" but thinking much less of the second half which he thought deteriorated into an "illogical and meandering chase story. It is difficult to believe the same man wrote both halves of the film."[29] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called it "a clever sci-fi fantasy ... with enough ingenuity and conviction to make it a successful diversion for those seeking novel rather than sophisticated entertainment."[30] Jean M. White of the Washington Post wrote that "Crichton spends too much time establishing his robot world and short-circuits suspense with long, arid stretches of Grade B Western."[31]

The film has a rating of 84% "Fresh" on Rotten Tomatoes based on 43 reviews. The site's consensus states: "Yul Brynner gives a memorable performance as a robotic cowboy in this amusing sci-fi/western hybrid."[32] Reviewing the DVD release in September 2008, The Daily Telegraph reviewer Philip Horne described the film as a "richly suggestive, bleakly terrifying fable—and Brynner's performance is chillingly pitch-perfect."[33]

American Film Institute lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – Nominated[34]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Robot Gunslinger – Nominated Villain[35]

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – Nominated Science Fiction Film[36]

After making the film, Crichton took a year off. "I was intensely fatigued by Westworld", he said later. "I was pleased but intimidated by the audience reaction. ... The laughs are in the wrong places. There was extreme tension where I hadn't planned it. I felt the reaction, and maybe the picture, was out of control."[3] He believed that the film had been misunderstood as warning of the dangers of technology: "Everyone remembers the scene in Westworld where Yul Brynner is a robot that runs amok. But there is a very specific scene where people discuss whether or not to shut down the resort. I think the movie was as much about that decision as anything. They just didn't really think it was really going to happen."[37] His real intention was to warn against corporate greed.[38]

For him the picture marked the end of "about five years of science fiction/monster pictures for me".[3] He took a break from the genre and wrote The Great Train Robbery.

Crichton did not make a film for another five years. He did try, and had one set up "but I insisted on a certain way of doing it and as a result it was never made."[39]

Network television airings

editWestworld was first aired on NBC television on February 28, 1976.[40] The network aired a slightly longer version of the film than was shown in theaters or subsequently released on home video. Some of the extra scenes that were added for the United States television version are:[citation needed]

- Brief fly-by exterior shot of the hovercraft zooming just a few feet above the desert floor. In the theatrical version, all scenes involving the hovercraft were interior shots only.

- The scenes with the scientists having a meeting in the underground complex was much longer, giving more insight into their "virus" problem with the robots.

- A scene of technicians talking in the locker room about the work load of each robot world.

- There was a longer discussion between Peter and the sheriff after his arrest when he shot the Gunslinger.

- A scene in Medieval World in which a guest is tortured on the rack, which appears in the theatrical version only as a still image, was restored.

- The Gunslinger's chase of Peter through the three worlds was also extended.

Legacy

editA sequel, Futureworld, was filmed in 1976, and produced by American International Pictures, and only distributed by MGM. Only Brynner returned from the original cast to reprise his Gunslinger character (in a dream sequence, as well as footage recapping the original), though it did provide details regarding the carnage: more than 50 guests killed and 95 staff members killed or wounded. Fred Karlin returned as composer.

Four years later, in 1980, the CBS television network aired a short-lived television series, Beyond Westworld, "which took the Futureworld concept of android doppelgangers, but ignored the movie itself, harking back to Westworld"[41] with new characters. Its poor ratings caused it to be canceled after only three of the five episodes aired.[citation needed] Only sound designer Richard S. Church was retained from the movie.

Crichton used similar plot elements—a high-tech amusement park running amok and a central control paralyzed by a power failure—in his bestselling novel Jurassic Park.

Westworld contains a reference to a computer virus, one of the earliest mentions of them in fiction. The analogy is made by the Chief Supervisor in a staff meeting where the spread of malfunctions across the park is discussed.[42]

In 1996, Westworld 2000, a video game sequel to the film, was released by Byron Preiss Multimedia.[43]

Beginning in 2002, trade publications reported that a Westworld remake starring Arnold Schwarzenegger was in production, and would be written by Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines screenwriters Michael Ferris and John Bracanto.[44][45][46] Tarsem Singh was originally slated to direct, but left the project. Quentin Tarantino was approached, but turned it down.[47] On January 19, 2011, Warner Bros announced that plans for the remake were still active.[48]

In August 2013, it was announced that HBO had ordered a pilot for a Westworld TV series, to be produced by J. J. Abrams, Jonathan Nolan, and Jerry Weintraub. Nolan and his wife Lisa Joy were set to write and executive produce the series, with Nolan directing the pilot episode.[49] Production began in July 2014 in Los Angeles.[50][51] The new series premiered October 2, 2016. On April 22, 2020, the series was renewed for a fourth season,[52] which premiered on June 26, 2022.

References

edit- ^ Westworld at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ a b Crichton p x

- ^ a b c d e GELMIS, JOSEPH (January 4, 1974). "Author of 'Terminal Man' Building Nonterminal Career: CRICHTON". Los Angeles Times. p. d12.

- ^ a b A Brief, Early History of Computer Graphics in Film Archived July 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Larry Yaeger, August 16, 2002 (last update). Retrieved March 24, 2010

- ^ a b c "Legends of Film: Paul Lazarus" (Podcast). December 27, 2014.

- ^ Crichton p. ix

- ^ Crichton p. x–xi

- ^ Crichton p. xvi

- ^ "Westworld". TCM. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (November 15, 2012). "Richard Benjamin on Peter O'Toole, celebrity treasure hunts, and Woody Allen". AVClub.com. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- ^ Friedman, Lester D. (2007). American Cinema of the 1970s: Themes and Variations. Camden: Rutgers University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-8135-4023-8.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Crichton p. xiii

- ^ a b Crichton p. xix

- ^ "Film Score Monthly CD: Coma/Westworld/The Carey Treatment". Filmscoremonthly.com. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ "Shooting Westworld".

- ^ Crichton p xvii

- ^ "The Whitney Family: Pioneers in Computer Animation". Tested.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ "Ed Manning BlocPix". Atariarchives.org. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ "Chapter 4: A HISTORY OF COMPUTER ANIMATION 3/20/92 (note that this article is in error about the year the film was made)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ American Cinematographer 54(11):1394–1397, 1420–1421, 1436–1437. November 1973.

- ^ "How Michael Crichton's 'Westworld' Pioneered Modern Special Effects", David A. Price, The New Yorker, May 16, 2013

- ^ a b "Westworld". Variety. United States. August 15, 1973. p. 12. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Day-by-day". Daily Variety. October 30, 1973. p. 164.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973". Variety. January 9, 1974. p. 19.

- ^ "All-time Film Rental Champs". Variety. January 7, 1976. p. 44.

- ^ Michael Crichton. Amazon Listing for Westworld. ISBN 0553084410.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 22, 1973). "The Screen: 'Westworld':Robots and Fantasies in Film by Crichton The Cast". The New York Times. p. 51. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (August 17, 1973). "'Westworld': Is it a look at tomorrow?" Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 1.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (October 24, 1973). "Acting Out Fantasy in 'Westworld". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 11.

- ^ White, Jean M. (September 26, 1973). "Robots Run Amok". The Washington Post. D8.

- ^ "Westworld (1973)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ Horne, Philip (September 20, 2008). "Westworld: DVD of the week review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills Nominees" (PDF). afi.com. American Film Institute. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains Nominees" (PDF). afi.com. American Film Institute. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Ballot" (PDF). afi.com. American Film Institute. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ Yakai, Kathy (February 1985). "Michael Crichton / Reflections of a New Designer". Compute!. pp. 44–45. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ Tallerico, Brian (September 30, 2016). "The Long, Weird History of the Westworld Franchise". Vulture. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- ^ Michael Owen (January 28, 1979). "Director Michael Crichton Films a Favorite Novelist". The New York Times. p. D17.

- ^ "TV Tango Saturday Night Movies Broadcast Date for Westworld". Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ Sherman, Fraser A. (2010) Screen Enemies of the American Way McFarland pg 155

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0070909/synopsis: IMDb synopsis of Westworld. Retrieved June 15, 2015. [user-generated source]

- ^ "Westworld 2000". MobyGames. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ "Westworld Headed Back To Screen". Empire. August 12, 2005. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (March 13, 2002). "Arnold back for 'Westworld,' 'Conan' redos". Variety. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ "Scifiwire". Scifi.com. Archived from the original on November 15, 2007.

- ^ Hostel: Part II DVD commentary track.

- ^ Kit, Borys. "EXCLUSIVE: 'Lethal Weapon,' 'Wild Bunch' Reboots Revived After Warner Bros. Exec Shuffle". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Hertzfeld, Laura (August 30, 2013). "HBO orders 'Westworld' adaptation from J. J. Abrams". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ Fienberg, David. "Press Tour: July 2014 HBO Executive Session Live-Blog". Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ Laratonda, Ryanne. "Los Angeles Film & TV Production Listings". Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ "'Westworld' Renewed for Season 4 at HBO". April 22, 2020.

External links

edit- Westworld at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Westworld at IMDb

- Westworld at the TCM Movie Database

- Westworld at AllMovie

- Westworld at Rotten Tomatoes