The occupation of the Baltic states was a period of annexation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania by the Soviet Union from 1940 until its dissolution in 1991. For a brief period, Nazi Germany occupied the Baltic states after it invaded the Soviet Union in 1941.

| Part of World War II and the Cold War | |

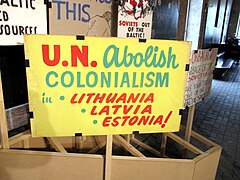

A protest sign from the 1970s calling on the United Nations to abolish Soviet colonialism in the Baltic states | |

| Date | 15 June 1940 – 6 September 1991Military presence: 28 September 1939 – 31 August 1994 |

|---|---|

| Location | Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania |

| Participants | |

| Outcome |

|

The initial Soviet invasion and occupation of the Baltic states began in June 1940 under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, made between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in August 1939 before the outbreak of World War II.[1][2] The three independent Baltic countries were annexed as constituent Republics of the Soviet Union in August 1940. Most Western countries did not recognise this annexation, and considered it illegal.[3][4] In July 1941, the occupation of the Baltic states by Nazi Germany took place, just weeks after its invasion of the Soviet Union. The Third Reich incorporated them into its Reichskommissariat Ostland. In 1944, the Soviet Union recaptured most of the Baltic states as a result of the Red Army's Baltic Offensive, trapping the remaining German forces in the Courland Pocket until their formal surrender in May 1945.[5]

During the 1944–1991 Soviet occupation many people from Russia and other parts of the former USSR were settled in the three Baltic countries, while the local languages, religion and customs were suppressed in an "extremely violent and traumatic" occupation.[6][7] Colonization of the three Baltic countries included mass executions, deportations and repression of the native population.

While there has been a broad international consensus that the Baltic states were illegally occupied and annexed,[8][9][10][11][12][13] the Soviet Union never acknowledged that they were forcefully taken over.[14] The post-Soviet government of Russia maintains the claim that the incorporations of Baltic states was in accordance with international law,[15][16] and school textbooks state that the Baltic states voluntarily joined the Soviet Union after home-grown popular socialist revolutions.[17] As most Western governments maintained that Baltic sovereignty had not been legitimately overridden,[18] they thus continued to recognise the Baltic states as sovereign political entities represented by the Baltic Legations, which functioned in Washington and elsewhere as governments in exile.[19]

The Baltic states regained de facto independence in 1991 during the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Russia started to withdraw its troops from the Baltics starting with Lithuania in August 1993. However, it was a violent process and Soviet forces killed several Latvians and Lithuanians.[20] The full withdrawal of troops deployed by Moscow ended in August 1994.[citation needed] Russia officially ended its military presence in the Baltics in August 1998 by decommissioning the Skrunda-1 radar station in Latvia. The dismantled installations were repatriated to Russia and the site returned to Latvian control, with the last Russian soldier leaving Baltic soil in October 1999.[21][22]

Background

editEarly in the morning of 24 August 1939, the Soviet Union and Germany signed a ten-year non-aggression pact, called the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact. The pact contained a secret protocol by which the states of Northern and Eastern Europe were divided into German and Soviet "spheres of influence".[23] In the north, Finland, Estonia and Latvia were assigned to the Soviet sphere.[23] Poland was to be partitioned in the event of its "political rearrangement"—the areas east of the Narev, Vistula and San Rivers going to the Soviet Union while Germany would occupy the west.[23] Lithuania, adjacent to East Prussia, would be in the German sphere of influence, although a second secret protocol agreed in September 1939 assigned the majority of Lithuanian territory to the Soviet Union.[24] Under the secret protocol, Lithuania would regain its historical capital Vilnius, previously subjugated during the inter-war period by Poland.

Following the end of the Soviet invasion of Poland on 6 October, the Soviets pressured Finland and the Baltic states to conclude mutual assistance treaties. The Soviets questioned the neutrality of Estonia after the escape of an interned Polish submarine on 18 September. On 24 September, the Estonian foreign minister was given an ultimatum: The Soviets demanded a treaty of mutual assistance to establish military bases in Estonia.[25][26] The Estonians were coerced to accept naval, air and army bases on two Estonian islands and at the port of Paldiski.[25] The corresponding agreement was signed on 28 September 1939. Latvia followed on 5 October 1939 and Lithuania shortly thereafter, on 10 October 1939. The agreements permitted the Soviet Union to establish military bases on the Baltic states' territory for the duration of the European war[26] and to station 25,000 Soviet soldiers in Estonia, 30,000 in Latvia and 20,000 in Lithuania starting October 1939.

Soviet occupation and annexation (1940–1941)

editIn May 1940, the Soviets turned to the idea of direct military intervention, but still intended to rule through puppet regimes.[27] Their model was the Finnish Democratic Republic, a puppet regime set up by the Soviets on the first day of the Winter War.[28] The Soviets organised a press campaign against the allegedly pro-Allied sympathies of the Baltic governments. In May 1940, the Germans invaded France, which was overrun and occupied a month later. In late May and early June 1940, the Baltic states were accused of military collaboration against the Soviet Union by holding meetings the previous winter.[29]: 43 On 15 June 1940, the Lithuanian government was extorted to agree to the Soviet ultimatum and permit the entry of an unspecified number of Soviet troops. President Antanas Smetona proposed armed resistance to the Soviets but the government refused,[30] proposing their own candidate to lead the regime.[27] However, the Soviets refused this proposal and sent Vladimir Dekanozov to take charge while the Red Army occupied the state.[31]

On 16 June 1940, Latvia and Estonia also received ultimata. The Red Army occupied the two remaining Baltic states shortly thereafter. The Soviets dispatched Andrey Vyshinsky to oversee the takeover of Latvia and Andrey Zhdanov to Estonia. On 18 and 21 June 1940, new "popular front" governments were formed in each Baltic country, made up of Communists and fellow travelers.[31] Under Soviet surveillance, the new governments arranged rigged elections for new "people's assemblies." Voters were presented with a single list, and no opposition movements were allowed to file candidates. To get the required turnout to 99.6%, votes were forged.[29]: 46 A month later when the new assemblies met their sole item of business for each of them was a resolution to join the Soviet Union. In each case, the resolution passed by acclamation. The Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union duly accepted the requests in August, thus sanctioning them under Soviet law. Lithuania was incorporated into the Soviet Union on 3 August, Latvia on 5 August, and Estonia on 6 August 1940.[31] The deposed presidents of Estonia and Latvia, Konstantin Päts and Kārlis Ulmanis, were deported to the USSR and imprisoned. They died later in the Tver region[32] and Central Asia respectively. In June 1941, the new Soviet governments carried out mass deportations of "enemies of the people". Estonia alone lost an estimated 60,000 citizens.[29]: 48 Consequently, many Balts initially greeted the Germans as liberators when they invaded a week later.[33]

The Soviet Union immediately started to erect border fortifications along its newly acquired western border — the so-called Molotov Line.

German occupation (1941–1945)

editOstland province and the Holocaust

editOn 22 June 1941 the Germans invaded the Soviet Union. The Baltic states, recently Sovietized by threats, force, and fraud, generally welcomed the German armed forces.[34] In Lithuania, a revolt broke out and an independent provisional government was established. As the German armies approached Riga and Tallinn, attempts to reestablish national governments were made. Baltic citizens hoped that the Germans would reestablish Baltic independence. Such hopes soon evaporated and Baltic cooperation became less forthright or ceased altogether.[35] The Germans aimed to annex the Baltic territories into the Third Reich where "suitable elements" would be assimilated and "unsuitable elements" exterminated. In practice, the implementation of occupation policy was more complex; for administrative convenience the Baltic states were included with Belorussia in the Reichskommissariat Ostland.[36] The area was governed by Hinrich Lohse who was obsessed with bureaucratic regulations.[36] The Baltic area was the only eastern region intended to become a full province of the Third Reich.[37]

Nazi racial attitudes to the peoples of the three Baltic countries differed between Nazi authorities. In practice, racial policies were directed not against the majority of Balts but rather against the Jews. Large numbers of Jews were living in the major cities, notably in Vilnius, Kaunas and Riga. The German mobile killing units slaughtered hundreds of thousands of Jews; Einsatzgruppe A, assigned to the Baltic area, was the most effective of four units.[37] German policy forced the Jews into ghettos. In 1943 Heinrich Himmler ordered his forces to liquidate the ghettos and to transfer the survivors to concentration camps. Some Latvians and Lithuanian conscripts collaborated actively in the killing of Jews, and the Nazis managed to provoke pogroms locally, especially in Lithuania.[38] Only about 75 percent of Estonian and 10 percent of Latvian and Lithuanian Jews survived the war. However, for the majority of Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians, the German rule was less harsh than Soviet rule had been, and it was less brutal than German occupations elsewhere in eastern Europe.[39] Local puppet regimes performed administrative tasks and schools were permitted to function. However, most people were denied the right to own land or businesses.[40]

Baltic nationals within the Soviet forces

editThe Soviet administration had forcibly incorporated the Baltic national armies at the wake of the occupation in 1940. Most of the senior officers were arrested and many of them murdered.[41] During the German invasion, the Soviets conducted a forced general mobilisation that took place in violation of the international law. Under the Geneva Conventions, this act of violence is seen as a grave breach and war crime, because the mobilised men were treated as arrestants from the very beginning. In comparison with the general mobilisation proclaimed in the Soviet Union, the age range was extended by 9 years in the Baltics; all reserve officers were also taken. The aim was to deport all men capable to fight to Russia, where they were sent to convict camps. Almost half of them perished because of the transportation conditions, slave labour, hunger, diseases, and the repressive measures of the NKVD.[41][42] In addition, destruction battalions were formed under the command of the NKVD.[43] Hence, Baltic nationals fought in both German and Soviet army ranks. There was the 201st Latvian Rifle Division. The 308th Latvian Rifle Division was awarded the Red Banner Order after the expulsion of the Germans from Riga in the autumn of 1944.[44]

An estimated 60,000 Lithuanians were drafted into the Red Army.[45] During 1940, on the basis of disbanded Lithuanian Army, Soviet authorities organized 29th Territorial Rifle Corps. Decrease in quality of life and service conditions, forceful indoctrination of Communist ideology, caused discontent of recently Sovietized military units. Soviet authorities responded with repressions against Lithuanian officers of the 29th Corps, arresting over 100 officers and soldiers and subsequently executing around 20 in Autumn 1940. By that time allegedly near 3,200 officers and soldiers of 29th Corps were considered "politically unreliable". Due to high tensions and soldiers' discontent the 26th Cavalry Regiment was disbanded. During the 1941 June deportations over 320 officers and soldiers of 29th Corps were arrested and deported to concentration camps or executed. The 29th Corps collapsed with the German invasion into Soviet Union: on June 25–26 a rebellion broke in its 184th Rifle Division. The other division of the 29th Corps, the 179th Rifle Division lost most of its soldiers during the retreat from Germans mostly to deserting of its soldiers. A total of less than 1,500 soldiers from initial strength of around 12,000 reached the area of Pskov by August 1941. By the second part of 1942, most of Lithuanians remaining in the Soviet ranks as well as male war refugees from Lithuania were organized into 16th Rifle Division during its second formation. 16th Rifle Division, despite officially called "Lithuanian" and mostly commanded by officers of Lithuanian origin, including Adolfas Urbšas, was ethnically very mixed, with up to 1/4 of its personnel made of Jews and thus being the largest Jew formation of Soviet Army. Popular joke of those years said that 16th Division is called Lithuanian, because there are 16 Lithuanians among its ranks.

The 7000-strong 22nd Estonian Territorial Rifle Corps got heavily beaten in the battles around Porkhov during the German invasion in summer 1941, as 2000 were killed or wounded in action, and 4500 surrendered. The 25,000—30,000 strong 8th Estonian Rifle Corps lost 3/4 of its troops in the Battle of Velikiye Luki in winter 1942/43. It participated in the capture of Tallinn in September 1944.[41] About 20,000 Lithuanians, 25,000 Estonians, and 5000 Latvians died in the ranks of the Red Army and labor battalions.[42][44]

Baltic nationals in the German forces

editThe Nazi administration also conscripted Baltic nationals into the German armies. The Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force, composed of volunteers, was formed in 1944. The LTDF reached a size of roughly 10,000 men. Its goal was to fight the approaching Red Army, provide security and conduct anti-partisan operations within the territory claimed by Lithuanians. After brief engagements against Soviet and Polish partisans, the force self-disbanded.[46] Its leaders were arrested and sent to Nazi concentration camps,[47] and many of members were executed by the Nazis.[47] Latvian Legion, created in 1943, consisted of two conscripted divisions of the Waffen-SS. On 1 July 1944 the Latvian Legion had 87,550 men. Another 23,000 Latvians were serving as Wehrmacht "auxiliaries".[48] Among other battles, they participated in the Siege of Leningrad, in the Courland Pocket fighting,the defence of the Pomeranian Wall, at the Velikaya River for Hill "93,4" and in the defence of Berlin. The 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Estonian) was formed in January 1944 through conscription. Consisting of 38,000 men, it took part in the Battle of Narva, the Battle of Tannenberg Line, the Battle of Tartu, and Operation Aster.

Attempts to restore independence and the Soviet offensive of 1944

editThere were several attempts to restore independence during the occupation. On 22 June 1941 the Lithuanians overthrew Soviet rule two days before the Wehrmacht arrived in Kaunas, where the Germans then allowed a Provisional Government to function for over a month.[40] The Latvian Central Council was set up as an underground organisation in 1943, but it was destroyed by the Gestapo in 1945. In Estonia in 1941, Jüri Uluots proposed restoration of independence; later, by 1944, he had become a key figure in the secret National Committee. In September 1944, Uluots briefly became acting president of independent Estonia.[49] Unlike the French and the Poles, the Baltic states had no governments in exile located in the West. Consequently, Great Britain and the United States lacked any interest in the Baltic cause while the war against Germany remained undecided.[49] The discovery of the Katyn massacre in 1943 and callous conduct towards the Warsaw uprising in 1944 had cast shadows on relations; nevertheless, all three victors still displayed solidarity at the Yalta conference in 1945.[50]

By 1 March 1944 the siege of Leningrad was over and Soviet troops were on the border with Estonia.[51] The Soviets launched the Baltic Offensive, a twofold military-political operation to rout German forces, on 14 September. On 16 September the High Command of the German Army issued a plan in which Estonian forces would cover the German withdrawal.[52] The Soviets soon reached the Estonian capital Tallinn, where the NKVD's first mission was to stop anyone escaping from the state; however, many refugees did manage to escape to the West. The NKVD also targeted the members of the National Committee of the Republic of Estonia.[53] German and Latvian forces remained trapped in the Courland Pocket until the end of the war, capitulating on 10 May 1945.

Second Soviet occupation (1944–1991)

editResistance and deportations

editAfter reoccupying the Baltic states, the Soviets implemented a program of sovietization, which was achieved through large-scale industrialisation rather than by overt attacks on culture, religion or freedom of expression.[54] The Soviets carried out massive deportations to eliminate any resistance to collectivisation or support of partisans.[55] Baltic partisans, such as the Forest Brothers, continued to resist Soviet rule through armed struggle for a number of years.[56]

The Soviets had previously carried out mass deportations in 1940–41, but the deportations between 1944 and 1952 were even greater.[55] In March 1949 alone, the top Soviet authorities organised a mass deportation of 90,000 Baltic nationals.[57]

The total number deported in 1944–55 has been estimated at over half a million: 124,000 in Estonia, 136,000 in Latvia and 245,000 in Lithuania.[citation needed]

The estimated death toll among Lithuanian deportees between 1945 and 1958 was 20,000, including 5,000 children.[58]

The deportees were allowed to return after Nikita Khrushchev's secret speech in 1956 denouncing the excesses of Stalinism, however many did not survive their years of exile in Siberia.[55] After the war, the Soviets outlined new borders for the Baltic republics. Lithuania gained the regions of Vilnius and Klaipėda while the Russian SFSR annexed territory from the eastern parts of Estonia (5% of prewar territory) and Latvia (2%).[55]

Industrialization and immigration

editThe Soviets made large capital investments for energy resources and the manufacture of industrial and agricultural products. The purpose was to integrate the Baltic economies into the larger Soviet economic sphere.[59] In all three republics, manufacturing industry was developed resulting in some of the best industrial complexes in the sphere of electronics and textile production. The rural economy suffered from the lack of investments and the collectivization.[60] Baltic urban areas had been damaged during wartime and it took ten years to recuperate housing losses. New constructions were often of poor quality and ethnic Russian immigrants were favored in housing.[61] Estonia and Latvia received large-scale immigration of industrial workers from other parts of the Soviet Union that changed the demographics dramatically. Lithuania also received immigration but on a smaller scale.[59]

Ethnic Estonians constituted 88 percent before the war, but in 1970 the figure dropped to 60 percent. Ethnic Latvians constituted 75 percent, but the figure dropped 57 percent in 1970 and further down to 50.7 percent in 1989. In contrast, the drop in Lithuania was only 4 percent.[61] Baltic communists had supported and participated the 1917 October Revolution in Russia. However, many of them were killed during the Great Purge in the 1930s. The new regimes of 1944 were established mostly by native communists who had fought in the Red Army. However, the Soviets also imported ethnic Russians to fill political, administrative and managerial posts.[63]

Restorations of independence

editThe period of stagnation brought the crisis of the Soviet system. The new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985 and responded with glasnost and perestroika. They were attempts to reform the Soviet system from above to avoid revolution from below. The reforms occasioned the reawakening of nationalism in the Baltic republics.[64] The first major demonstrations against the environment were Riga in November 1986 and the following spring in Tallinn. Small successful protests encouraged key individuals and by the end of 1988 the reform wing had gained the decisive positions in the Baltic republics.[65] At the same time, coalitions of reformists and populist forces assembled under the Popular Fronts.[66] The Supreme Soviet of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic made the Estonian language the state language again in January 1989, and similar legislation was passed in Latvia and Lithuania soon after. The Baltic republics declared their aim for sovereignty: Estonia in November 1988, Lithuania in May 1989 and Latvia in July 1989.[67] The Baltic Way, that took place on 23 August 1989, became the biggest manifestation of opposition to the Soviet rule.[68] In December 1989, the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union condemned the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and its secret protocol as "legally untenable and invalid."[69]

On 11 March 1990 the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet declared Lithuania's independence.[70] Pro-independence candidates had received an overwhelming majority in the Supreme Soviet elections held earlier that year.[71] On 30 March 1990, seeing full restoration of independence not yet feasible due to large Soviet presence, the Estonian Supreme Soviet declared the Soviet Union an occupying power and announced the start of a transitional period to independence. On 4 May 1990, the Latvian Supreme Soviet made a similar declaration.[72] The Soviet Union immediately condemned all three declarations as illegal, saying that they had to go through the process of secession outlined in the Soviet Constitution of 1977. However, the Baltic states argued that the entire occupation process violated both international law and their own law. Therefore, they argued, they were merely reasserting an independence that still existed under international law.

By mid-June, after unsuccessful economic blockade of Lithuania, the Soviets started negotiations with Lithuania and the other two Baltic republics. The Soviets had a bigger challenge elsewhere, as the Russian Federal Republic proclaimed sovereignty in June.[73] Simultaneously the Baltic republics also started to negotiate directly with the Russian Federal Republic.[73] After the failed negotiations the Soviets made a dramatic but failed attempt to break the deadlock and sent in military troops killing twenty and injuring hundreds of civilians in what became known as the "Vilnius massacre" in Lithuania and "The Barricades" in Latvia during January 1991.[74] In August 1991, the hard-line members attempted to take control of the Soviet Union. A day after the coup on 21 August, the Estonians proclaimed full independence, after an independence referendum was held in Estonia on 3 March 1991,[75] alongside a similar referendum in Latvia the same month. It was approved by 78.4% of voters with an 82.9% turnout. Independence was restored by the Estonian Supreme Council on the night of 20 August.[75] The Latvian parliament made similar a declaration on the same day. The coup failed but the collapse of the Soviet Union became unavoidable.[76] After the coup collapsed, the Soviet government recognised the independence of all three Baltic states on 6 September 1991.

Withdrawal of Russian troops and decommissioning the radars

editThe Russian Federation assumed the burden and the subsequent withdrawal of the occupation force, consisting of about 150,000 former Soviet, now Russian, troops stationed in the Baltic states.[77] In 1992 there were still 120,000 Russian troops there,[78] as well as a large number of military pensioners, particularly in Estonia and Latvia.

During the period of negotiations, Russia hoped to retain facilities such as the Liepāja naval base, the Skrunda anti-ballistic missile radar station, the Ventspils space-monitoring station in Latvia and the Paldiski submarine base in Estonia, as well as transit rights to Kaliningrad through Lithuania.

Contention arose when Russia threatened to keep its troops where they were. Moscow tied its concessions to specific legislation guaranteeing the civil rights of ethnic Russians, which was seen as an implied threat in the West, in the U.N. General Assembly and by Baltic leaders, who viewed it as Russian imperialism.[78]

Lithuania was the first to see complete the withdrawal of Russian troops—on 31 August 1993[79]—owing in part to the Kaliningrad issue.[78]

Subsequent agreements to withdraw troops from Latvia were signed on 30 April 1994, and from Estonia on 26 July 1994.[80] Continued linkage on the part of Russia resulted in a threat by the U.S. Senate in mid-July to halt all aid to Russia in case the forces were not withdrawn by the end of August.[80] Final withdrawal was completed on 31 August 1994.[81] Some Russian troops remained stationed in Estonia in Paldiski until the Russian military base was dismantled and the nuclear reactors suspended operations on 26 September 1995.[82][83] Russia operated the Skrunda-1 radar station until it was decommissioned on 31 August 1998. The Russian Government then had to dismantle and remove the radar equipment; this work was completed by October 1999 when the site was returned to Latvia.[84] The last Russian soldier left the region that month, marking a symbolic end to the Russian military presence on Baltic soil.[85][86]

Civilian toll

edit54°41′18.9″N 25°16′14.0″E / 54.688583°N 25.270556°E.

During the 1940–1941 and 1944–1991 occupations 605,000 inhabitants of the three countries in total were either killed or deported (135,000 Estonians, 170,000 Latvians and 320,000 Lithuanians). Their properties and personal belonging were confiscated and given to newly arrived colonists – economic migrants, Soviet military, NKVD personnel, as well as functionaries of the Communist Party.[87]

The estimated human costs of the occupations are presented in the table below.[88]

| Period/action | Estonia | Latvia | Lithuania |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 1,126,413 (1934) | 1,905,000 (1935) | 2,575,400 (1938) |

| First Soviet Occupation | |||

| June 1941 deportation | 9,267

(2,409 executed) |

15,424

(9,400 died en route) |

17,500 |

| Victims of repressions

(arrest, torture, political trials imprisonment or other sanctions) |

8,000 | 21,000 | 12,900 |

| Extrajudicial executions | 2,000 | Not known | 3,000 |

| Nazi Occupation | |||

| Mass killing of local minorities | 992 Jews

300 Roma |

70,000 Jews

1,900 Roma |

196,000 Jews

~4,000 Roma |

| Killing of Jews from outside | 8,000 | 20,000 | Not known |

| Killing of other civilians | 7,000 | 16,300 | 45,000 |

| Forced labour | 3,000 | 16,800 | 36,500 |

| Second Soviet Occupation | |||

| Operation Priboi

1948–49 |

1949: 20,702

3,000 died en route |

1949: 42,231

8,000 died en route |

1948: 41,000

1949: 32,735 |

| Other deportations between 1945 and 1956 | 650 | 1,700 | 59,200 |

| Arrests and political imprisonment | 30,000

11,000 perished |

32,000 | 186,000 |

| Post-war partisans killed or imprisoned | 8,468

4,000 killed |

8,000

3,000 killed |

21,500 |

Aftermath

editThe Soviet Union and its successors have never paid reparations to the Baltic states.[89]

In the years following the reestablishment of Baltic independence, tensions have remained between indigenous Balts and Russian-speaking population in Estonia and Latvia. The UN noted the discriminatory position of the non-citizens in Latvia[90] and Human Rights Watch contended that the policy of Estonia towards its non-citizens was discriminatory.[91] According to Peter Elswege, a lack of attention to the rights of Russian-speaking and stateless individuals in the Baltic states has been noted by some experts, although all international organisations agree that no forms of systematic discrimination towards the Russian-speaking and often stateless population can be observed.[92]

In 1993, Estonia was noted for having problems concerning the successful integration of some who were permanent residents at the time Estonia gained independence.[93] The requirements for getting citizenship in Estonia were considered "relatively liberal" in 1996.[94] According to a 2008 report of Special Rapporteur on racism to United Nations Human Rights Council the representatives of the Russian speaking communities in Estonia say the most important form of discrimination in Estonia is not ethnic, but rather language-based (Para. 56). The rapporteur made several recommendations, including strengthening the Chancellor of Justice,[clarification needed] making it easier for persons of undefined nationality to obtain citizenship, and opening a discussion on language policy to elaborate strategies better reflecting the multilingual character of the society (paras. 89–92).[12] Estonia has been criticized by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination strong emphasis on Estonian language in the state Integration strategy; usage of punitive approach for promoting Estonian language; restrictions of the usage of minority language in public services; low level of minority representation in political life; persistently high number of persons with undetermined citizenship, etc.[95]

According to Israeli author Yaël Ronen of the Minerva Center for Human Rights at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, illegal regimes typically take measures to change the demographic structure of the territory held by the regime, usually via two methods: the forced removal of the local population and transfer their own populations into the territory.[96] He cites the case of the Baltic states as an example of where this phenomenon has occurred, with the deportations of 1949 combined with large waves of immigration in 1945–50 and 1961–70.[96] When the illegal regime transitioned to a lawful regime in 1991, the status of these settlers became an issue.[96]

Author Aliide Naylor notes the lingering legacy of Soviet modernist architecture in the region, with many iconic Soviet structures in the Baltic states falling into disrepair or being demolished completely. There are ongoing debates surrounding their future.[97]

Legal and historical perspectives

editThe Baltic states' governments themselves,[8][9] the United States[98][99] and its courts of law,[100] the European Parliament,[10][101][102] the European Court of Human Rights[11] and the United Nations Human Rights Council[12] have all stated that these three countries were invaded, occupied and illegally incorporated into the Soviet Union under provisions of the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[13] There followed occupation by Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1944 and then again occupation by the Soviet Union from 1944 to 1991.[103][104][105][106][107] This policy of non-recognition has given rise to the principle of legal continuity of the Baltic states, which holds that de jure, or as a matter of law, the Baltic states remained independent states under illegal occupation throughout the period from 1940 to 1991.[108][109][110]

However, the Soviet Union never formally acknowledged that its presence in the Baltics was an occupation or that it had annexed these states[14] and considered the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic, Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic and Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republics three of its constituent republics. On the other hand, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic recognized in 1991 that the events of 1940 were an "annexation".[111]

Historically revisionist[112] Russian historiography and school textbooks continue to maintain that the Baltic states voluntarily joined the Soviet Union after their each of their peoples carried out socialist revolutions independent of Soviet influence.[113] The post-Soviet government of Russia and its state officials insist that incorporation of the Baltic states was in accordance with international law[114][115] and gained de jure recognition by the agreements made in the February 1945 Yalta and the July–August 1945 Potsdam conferences and by the 1975 Helsinki Accords,[116][117] which declared the inviolability of existing frontiers.[118] However, this claim has been described by British army think tank CHACR as both "nefarious" and a "horrifying insult" — part of an intentional propaganda campaign to spread a myth of Baltic "incorporation".[119] Russia also agreed to Europe's demand to "assist persons deported from the occupied Baltic states" upon joining the Council of Europe in 1996.[120][121][122] Also, when the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic signed a separate treaty with Lithuania in 1991, it acknowledged the 1940 annexation as a violation of Lithuanian sovereignty and recognised the de jure continuity of the Lithuanian state.[123][124]

State continuity of the Baltic states

editThe Baltic claim of continuity with the pre-war republics has been accepted by most Western powers.[125] As a consequence of the policy of non-recognition of the Soviet seizure of these countries,[108][109] combined with the resistance by the Baltic people to the Soviet regime, the uninterrupted functioning of rudimentary state organs in exile in combination with the fundamental legal principle of ex injuria jus non oritur, that no legal benefit can be derived from an illegal act, the seizure of the Baltic states was judged to be illegal[126] thus sovereign title never passed to the Soviet Union and the Baltic states continued to exist as subjects of international law.[127]

The official position of Russia, which chose in 1991 to be the legal and direct successor of the USSR,[128] is that Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania joined the Soviet Union freely and of their own accord in 1940, and, with the dissolution of the USSR, these countries became newly created entities in 1991. Russia's stance is based upon the desire to avoid financial liability, since acknowledging the Soviet occupation would set the stage for future compensation claims from the Baltic states.[129]

Soviet and Russian historiography

editSoviet historians saw the 1940 annexation as a voluntary entry into the USSR by the Balts.[130] Soviet historiography promoted the interests of Russia and the USSR in the Baltic area, and it reflected the belief of most Russians that they had moral and historical rights to control and to Russianize the entire former Russian empire.[131] To Soviet historians, the 1940 annexation was not only a voluntary entry but was also the natural thing to do. This concept taught that the military security of mother Russia was solidified and that nothing could argue against it.[132]

Soviet point of view

editPrior to perestroika, the Soviet Union denied the existence of the secret protocols and viewed the events of 1939–40 as follows:[133]

- the government of the Soviet Union suggested that the governments of the Baltic countries conclude mutual assistance treaties between the countries.

- Pressure from working people forced the governments of the Baltic countries to accept this suggestion. The pacts were then signed[134]

- These pacts allowed the USSR to station a limited number of Red Army units in the Baltic countries.[135]

- Economic difficulties and dissatisfaction of the populace with Baltic government policies had impeded fulfilment of the pacts, and the populace revolted against the Baltic governments' political orientation towards Germany in a revolution in June 1940.

- To guarantee fulfilment of the pact additional military units entered the Baltic countries, welcomed by workers, who demanded the resignations of the governments.

- In June workers demonstrated under the leadership of the Communist parties of the Baltic countries.

- The fascist governments were overthrown, and workers' governments formed.

- In July 1940, elections for Baltic parliaments were held.

- The "Working People's Unions", created by the Communist parties, received the majority of the votes.[136]

- The parliaments adopted declarations restoring Soviet powers in Baltic countries and proclaimed the Soviet Socialist Republics. Declarations of Estonia's, Latvia's and Lithuania's wishes to join the USSR were adopted and the Supreme Soviet of the USSR was petitioned accordingly.

- The requests were approved by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.

The Stalin-edited Falsifiers of History, published in 1948, says the June 1940 invasions were needed because "[p]acts had been concluded with the Baltic States, but there were as yet no Soviet troops there capable of holding the defences".[137] It also states regarding those invasions that "[o]nly enemies of democracy or people who had lost their senses could describe those actions of the Soviet Government as aggression".[138]

In the reassessment of Soviet history during perestroika, the USSR condemned the 1939 secret protocol between itself and Germany that led to the invasion and occupations in the Baltic countries.[133]

Russian historiography in the post-Soviet era

editDuring the Soviet era, there was relatively little interest in the history of the Baltic states, which historians generally treated as a single entity due to the uniformity of Soviet policy in these territories.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, two general camps have evolved in Russian historiography. One, the liberal-democratic (либерально-демократическое), condemns Stalin's actions and the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact and does not consider the Baltic states as having joined the USSR voluntarily. The other, the national-patriotic (национально-патриотическое), contends that the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact was necessary to the security of the Soviet Union, that the Baltics' joining the USSR was the will of the proletariat—both in line with the politics of the Soviet period, "the 'need to ensure the security of the USSR', 'people's revolution' and 'joining voluntarily'"—and that supporters of Baltic independence were the operatives of western intelligence agencies seeking to topple the USSR.[112]

Soviet-Russian historian Vilnis Sīpols argues that Stalin's ultimatums of 1940 were defensive measures taken against of the German threat and had no connection with the 'socialist revolutions' in the Baltic states.[139] The arguments that the USSR had to annex the Baltic states in order to defend the security of those countries and to avoid German invasion into the three republics can also be found in the college textbook "The Modern History of Fatherland".[140]

Sergey Chernichenko, a jurist and vice-president of the Russian Association of International Law, argues there was no declared state of war between the Baltic states and the Soviet Union in 1940, and that Soviet troops occupied the Baltic states with their agreement, and also that USSR violation of prior treaty provisions did not constitute occupation. Subsequent annexation was neither an act of aggression nor forcible and was completely legal according to international law as of 1940. Accusations of "deportation" of Baltic nationals by the Soviet Union are therefore baseless, he says, as individuals cannot be deported within their own country. He claims the Waffen-SS was being convicted at Nuremberg as a criminal organization and their commemoration in the "openly encouraged pro-Nazi" (откровенно поощряются пронацистские) Baltics as heroes seeking to liberate the Baltics from the Soviets) is an act of "nationalistic blindness" (националистическое ослепление). With regard to the current situation in the Baltics, Chernichenko contends the "theory of occupation" is the official thesis used to justify the "discrimination of Russian-speaking inhabitants" in Estonia and Latvia and prophesies the three Baltic governments will fail in their "attempt to rewrite history".[141]

According to the revisionist historian Oleg Platonov "from the point of view of the national interests of Russia, unification was historically just, as it returned to the composition of the state ancient Russian lands, albeit partially inhabited by other peoples". The Molotov–Ribbentrop pact and protocols, including the dismemberment of Poland, merely redressed the tearing away from Russia of its historical territories by "anti-Russian revolution" and "foreign intervention".[142]

On the other hand, Professor and Dean of the School of International Relations and Vice-Rector of Saint Petersburg State University, Konstantin K. Khudoley views the 1940 annexation of the Baltic states as involuntary. He considers the elections were not free and fair and the decisions of the newly elected parliaments to join the Soviet Union cannot be considered legitimate as these decisions were not approved by the upper chambers of the parliaments of the respective Baltic states. He also contends that the annexation of the Baltic states had no military value in defence of possible German aggression, as it bolstered anti-Soviet public opinion in future allies Britain and the US and turned the native populations against the Soviet Union: the subsequent guerrilla movement in the Baltic states after the Second World War caused domestic problems for the Soviet Union.[143]

Position of the Russian Federation

editWith the advent of Perestroika and its reassessment of Soviet history, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR in 1989 condemned the 1939 secret protocol between Germany and the Soviet Union that had led to the division of Eastern Europe and the invasion and occupation of the three Baltic countries.[citation needed]

While this action did not state the Soviet presence in the Baltics was an occupation, the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic and Republic of Lithuania affirmed so in a subsequent agreement in the midst of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Russia, in the preamble of its 29 July 1991, "Treaty Between the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic and the Republic of Lithuania on the Basis for Relations between States", declared that once the USSR had eliminated the consequences of the 1940 annexation which violated Lithuania's sovereignty, Lithuania–Russia relations would further improve.[124]

However, Russia's current official position directly contradicts its earlier rapprochement with Lithuania[144] as well as its signature of membership to the Council of Europe, where it agreed to the obligations and commitments including "iv. as regards the compensation for those persons deported from the occupied Baltic states and the descendants of deportees, as stated in Opinion No. 193 (1996), paragraph 7.xii, to settle these issues as quickly as possible....".[122][145] The Russian government and state officials maintain now that the Soviet annexation of the Baltic states was legitimate[146] and that the Soviet Union liberated the countries from the Nazis.[147] They assert that the Soviet troops initially entered the Baltic countries in 1940 following agreements and the consent of the Baltic governments. Their position is that the USSR was not in a state of war or engaged in combat activities on the territories of the three Baltic states, therefore, the word "occupation" cannot be used.[148] "The assertions about [the] 'occupation' by the Soviet Union and the related claims ignore all legal, historical and political realities, and are therefore utterly groundless".—Russian Foreign Ministry.

This particular Russian viewpoint is called the "Myth of 1939–40" by international affairs professor David Mendeloff,[149] who states that the assertion that Soviet Union neither "occupied" the Baltic states in 1939 nor "annexed" them the following year is widely held and deeply embedded in Russian historical consciousness.[150]

Treaties affecting USSR–Baltic relations

editThe Baltic states proclaimed independence after the signing of the Armistice, and Bolshevik Russia invaded at the end of 1918.[151] Izvestia wrote in its 25 December 1918, issue: "Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are directly on the road from Russia to Western Europe and therefore a hindrance to our revolutions... This separating wall has to be destroyed". Bolshevik Russia, however, did not gain control of the Baltic States and in 1920 concluded peace treaties with all three of them. Subsequently, at the initiative of the Soviet Union,[152] additional non-aggression treaties were concluded with all three Baltic States:

Timeline

editSee also

edit- Kersten Committee

- January 1991 events in the aftermath of the Act of the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania, resulting in deaths and injuries

- Museum of Occupations, Tallinn, a project by the Kistler-Ritso Estonian Foundation

- Occupations of Latvia

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Russia involvement in regime change

- State continuity of the Baltic states

- Territorial changes of the Baltic states

- United States resolution on the 90th anniversary of the Latvian Republic

- Welles Declaration

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Taagepera, Rein (1993). Estonia: return to independence. Westview Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0813311999.

- ^ Ziemele, Ineta (2003). "State Continuity, Succession and Responsibility: Reparations to the Baltic States and their Peoples?". Baltic Yearbook of International Law. 3. Martinus Nijhoff: 165–190. doi:10.1163/221158903x00072.

- ^ Kaplan, Robert B.; Baldauf, Richard B. Jr. (2008). Language Planning and Policy in Europe: The Baltic States, Ireland and Italy. Multilingual Matters. p. 79. ISBN 978-1847690289. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

Most Western countries had not recognised the incorporation of the Baltic States into the Soviet Union, a stance that irritated the Soviets without ever becoming a major point of conflict.

- ^ Kavass, Igor I. (1972). Baltic States. W. S. Hein. ISBN 978-0930342418. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

The forcible military occupation and subsequent annexation of the Baltic States by the Soviet Union remains to this day (written in 1972) one of the serious unsolved issues of international law

- ^ Davies, Norman (2001). Dear, Ian (ed.). The Oxford companion to World War II. Michael Richard Daniell Foot. Oxford University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0198604464.

- ^ "How Russian Disinformation Targets the Former Soviet Bloc Around WWII Anniversaries - CHACR". 6 July 2020.

- ^ Vardys, Vytas Stanley (Summer 1964). "Soviet Colonialism in the Baltic States: A Note on the Nature of Modern Colonialism". Lituanus. 10 (2). ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ a b The Occupation of Latvia Archived 2007-11-23 at the Wayback Machine at Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia

- ^ a b "22 September 1944 from one occupation to another". Estonian Embassy in Washington. 22 September 2008. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

For Estonia, World War II did not end, de facto, until 31 August 1994, with the final withdrawal of former Soviet troops from Estonian soil.

- ^ a b Motion for a resolution on the Situation in Estonia Archived 29 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine by the European Parliament, B6-0215/2007, 21.5.2007; passed 24.5.2007 . Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ a b European Court of Human Rights cases on Occupation of Baltic States

- ^ a b c "Distr. General A/HRC/7/19/Add.2 17 March 2008 Original: English, Human Rights Council Seventh session Agenda item 9: Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Forms of Intolerance, Follow-up to and Implementation of the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action – Report of the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, Doudou Diène, Addendum, Mission to Estonia" (PDF). Documents on Estonia. United Nations Human Rights Council. 20 February 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ a b Mälksoo, Lauri (2003). Illegal Annexation and State Continuity: The Case of the Incorporation of the Baltic States by the USSR. Leiden & Boston: Brill. ISBN 9041121773.

- ^ a b Marek (1968). p. 396. "Insofar as the Soviet Union claims that they are not directly annexed territories but autonomous bodies with a legal will of their own, they (The Baltic SSRs) must be considered puppet creations, exactly in the same way in which the Protectorate or Italian-dominated Albania have been classified as such. These puppet creations have been established on the territory of the independent Baltic states; they cover the same territory and include the same population."

- ^ Combs, Dick (2008). Inside The Soviet Alternate Universe. Penn State Press. pp. 258, 259. ISBN 978-0271033556. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

The Putin administration has stubbornly refused to admit the fact of Soviet occupation of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia following World War II, although Putin has acknowledged that in 1989, during Gorbachev's reign, the Soviet parliament officially denounced the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, which led to the forcible incorporation of the three Baltic states into the Soviet Union.

- ^ Bugajski, Janusz (2004). Cold peace. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 109. ISBN 0275983625. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

Russian officials persistently claim that the Baltic states entered the USSR voluntarily and legally at the close of World War II and failed to acknowledge that Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were under Soviet occupation for fifty years.

- ^ Cole, Elizabeth A. (2007). Teaching the violent past: history education and reconciliation. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 233–234. ISBN 978-0742551435.

- ^ Quiley, John (2001). "Baltic Russians: Entitled Inhabitants or Unlawful Settlers?". In Ginsburgs, George (ed.). International and national law in Russia and Eastern Europe [Volume 49 of Law in Eastern Europe]. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 327. ISBN 9041116540.

- ^

"Baltic article". The World & I. 2 (3). Washington Times Corp: 692. 1987.

- Shtromas, Alexander; Faulkner, Robert K.; Mahoney, Daniel J. (2003). "Soviet Conquest of the Baltic states". Totalitarianism and the prospects for world order: closing the door on the twentieth century. Applications of political theory. Lexington Books. p. 263. ISBN 978-0739105337.

- ^ "Suing Gorbachev 31 years after the USSR's collapse, a group of Lithuanians sought to hold its last leader to account".

- ^ The Weekly Crier (1999/10) Archived 2013-06-01 at the Wayback Machine Baltics Worldwide. Accessed 11 June 2013.

- ^ "Russia Pulls Last Troops Out of Baltics" The Moscow Times. 22 October 1999.

- ^ a b c Text of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact Archived 14 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, executed August 23, 1939

- ^ Christie, Kenneth, Historical Injustice and Democratic Transition in Eastern Asia and Northern Europe: Ghosts at the Table of Democracy, RoutledgeCurzon, 2002, ISBN 0700715991

- ^ a b Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 110.

- ^ a b The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania by David J. Smith, Page 24, ISBN 0415285801

- ^ a b Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 113.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 112.

- ^ a b c Buttar, Prit (2013). Between Giants. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1780961637.

- ^ Robert van Voren (2011). Undigested Past: The Holocaust in Lithuania. Brill. ISBN 9789401200707.

- ^ a b c Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 114.

- ^ Turtola, Martti (2003). Presidentti Konstantin Päts. Suomi ja Viro eri teillä. Keuruu.

- ^ Gerner & Hedlund (1993). p. 59.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 115.

- ^ "Baltic states – region, Europe". britannica.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ a b Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 116.

- ^ a b Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 117.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 118.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 119.

- ^ a b Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 120.

- ^ a b c "Nõukogude ja Saksa okupatsioon (1940–1991)". Eesti. Üld. Vol. 11. Eesti entsüklopeedia. 2002. pp. 311–323.

- ^ a b Estonian State Commission on Examination of Policies of Repression (2005). "Human Losses" (PDF). The White Book: Losses inflicted on the Estonian nation by occupation regimes. 1940–1991. Estonian Encyclopedia Publishers. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013.

- ^ Indrek Paavle, Peeter Kaasik [in Estonian] (2006). "Destruction battalions in Estonia in 1941". In Toomas Hiio [in Estonian]; Meelis Maripuu; Indrek Paavle (eds.). Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Tallinn. pp. 469–493.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Alexander Statiev. The Soviet counterinsurgency in the western borderlands. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 77

- ^ Romuald J. Misiunas, Rein Taagepera. Baltic Years of Dependence 1940—1990. Tallinn, 1997, p. 32

- ^ Bubnys, Arūnas (1998). Vokiečių okupuota Lietuva (1941–1944). Vilnius: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras. pp. 409–423. ISBN 9986757126.

- ^ a b Mackevičius, Mečislovas (Winter 1986). "Lithuanian resistance to German mobilization attempts 1941–1944". Lituanus. 4 (32). ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Mangulis, Visvaldis (1983). Latvia in the Wars of the 20th Century. Princeton Junction, NJ: Cognition Books. ISBN 0912881003. OCLC 10073361.

- ^ a b Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 121.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 123.

- ^ Bellamy (2007). p. 621.

- ^ Bellamy (2007). p. 622.

- ^ Bellamy (2007). p. 623.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 126.

- ^ a b c d Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 129.

- ^ Petersen, Roger (2001). Resistance and Rebellion: Lessons from Eastern Europe. Studies in Rationality and Social Change. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511612725. ISBN 9780511612725.

- ^ Strods, Heinrihs; Kott, Matthew (2002). "The File on Operation 'Priboi': A Re-Assessment of the Mass Deportations of 1949". Journal of Baltic Studies. 33 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1080/01629770100000191. S2CID 143180209. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2008. "Erratum". Journal of Baltic Studies. 33 (2): 241. 2002. doi:10.1080/01629770200000071. S2CID 216140280. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ^ International Commission For the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania, Deportations of the Population in 1944–1953 Archived 2013-06-01 at the Wayback Machine, paragraph 14

- ^ a b Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 130.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 131.

- ^ a b Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 132.

- ^ Motyl, Alexander J. (2000). Encyclopedia of Nationalism, Two-Volume Set. Elsevier. pp. 494–495. ISBN 0080545246. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 139.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 147.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 149.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 150.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 151.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 154.

- ^ "Upheaval in the East; Soviet Congress Condemns '39 Pact That Led to Annexation of Baltics". The New York Times. 25 December 1989. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

The Congress condemned the secret protocols to the 1939 Soviet-German Nonaggression Treaty, which included a map delineating Soviet and German areas of interest, as 'legally untenable and invalid from the moment they were signed.'

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 158.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 160.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 162.

- ^ a b Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 164.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 187.

- ^ a b Nohlen, Dieter; Stöver, Philip (2010). Elections in Europe: A data handbook. Nomos. p. 567. ISBN 978-3832956097.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 189.

- ^ Holoboff, Elaine M.; Bruce Parrott (1995). "Reversing Soviet Military Occupation". National Security in the Baltic States. M.E. Sharpe. p. 112. ISBN 1563243601.

- ^ a b c Simonsen, S. Compatriot Games: Explaining the 'Diaspora Linkage' in Russia's Military Withdrawal from the Baltic States. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 53, No. 5. 2001

- ^ Holoboff, p 113

- ^ a b Holoboff, p 114

- ^ Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 191.

- ^ President of the Republic in Paldiski on 26 September 1995 Archived 9 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine Lennart Meri, the president of Estonia (1992–2001). 26 September 1995.

- ^ Last Russian Military Site Returned to Estonia. Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Jamestown Foundation. 27 September 1995.

- ^ Latvia takes over the territory of the Skrunda Radar Station Archived 29 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Embassy of the Republic of Latvia in Copenhagen, 31 October 1999. Accessed 22 July 2013.

- ^ Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania Archived 10 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine Lonely Planet. January 5, 2009. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ The Countries of the Former Soviet Union at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century Archived 10 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine Ian Jeffries. 2004. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ Abene, Aija; Prikulis, Juris (2017). Damage caused by the Soviet Union in the Baltic States: International conference materials (PDF). Riga: E-forma. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-9934-8363-1-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Pettai, Vello (2015). Transitional and Retrospective Justice in the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-1107049499. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ ERR (5 November 2015). "Justice minister goes behind PM's back to sign declaration about reparations for Soviet occupation". ERR. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Report of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination". UN. 1999. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ "Human Rights Watch submission to the Committee on the Rights of the Child concerning Estonia". Human Rights Watch. 21 November 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ van Elsuwege, Peter. "Russian-speaking minorities in Estonia and Latvia: problems of integration at the threshold of the European Union". European Centre for Minority Issues. p. 54. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ "Integrating Estonia's Non-Citizen Minority". Human rights watch. 1993. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ Ludwikowski, Rett R. (1996). Constitution-making in the region of former Soviet dominance. Duke University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0822318026. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "Concluding observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. Estonia" (PDF). UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. 23 September 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Yaël, Ronen (2010). "Status of Settlers Implanted by Illegal Territorial Regimes". In Crawford, James (ed.). British Year Book of International Law 2008. Vaughan Lowe. Oxford University Press. pp. 194–265. ISBN 978-0199580392. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "Soviet Modernism's Enduring Baltic Legacy". jacobin.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Feldbrugge, Ferdinand; Gerard Pieter van den Berg; William B. Simons (1985). Encyclopedia of Soviet law. Brill. p. 461. ISBN 9024730759. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

On March 26, 1949, the US Department of State issued a circular letter stating that the Baltic countries were still independent nations with their own diplomatic representatives and consuls.

- ^ Fried, Daniel (14 June 2007). "U.S.-Baltic Relations: Celebrating 85 Years of Friendship" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

From Sumner Wells' declaration of July 23, 1940, that we would not recognize the occupation. We housed the exiled Baltic diplomatic delegations. We accredited their diplomats. We flew their flags in the State Department's Hall of Flags. We never recognized in deed or word or symbol the illegal occupation of their lands.

- ^ Lauterpacht, E.; C. J. Greenwood (1967). International Law Reports. Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0521463807. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

The Court said: (256 N.Y.S.2d 196) "The Government of the United States has never recognized the forceful occupation of Estonia and Latvia by the Soviet Union of Socialist Republics nor does it recognize the absorption and incorporation of Latvia and Estonia into the Union of Soviet Socialist republics. The legality of the acts, laws and decrees of the puppet regimes set up in those countries by the USSR is not recognized by the United States, diplomatic or consular officers are not maintained in either Estonia or Latvia and full recognition is given to the Legations of Estonia and Latvia established and maintained here by the Governments in exile of those countries

- ^ Dehousse, Renaud (1993). "The International Practice of the European Communities: Current Survey". European Journal of International Law. 4 (1): 141. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.ejil.a035821. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2006.

- ^ European Parliament (13 January 1983). "Resolution on the situation in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania". Official Journal of the European Communities. C. 42/78. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ "Russia and Estonia agree borders". BBC. 18 May 2005. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

Five decades of almost unbroken Soviet occupation of the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania ended in 1991

- ^ Country Profiles: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania Archived 31 July 2003 at the Wayback Machine at UK Foreign Office

- ^ Saburova, Irina (1955). "The Soviet Occupation of the Baltic States". Russian Review. 14 (1). Blackwell Publishing: 36–49. doi:10.2307/126075. JSTOR 126075.

- ^ See, for instance, the position expressed by the European Parliament, which condemned "the fact that the occupation of these formerly independent and neutral States by the Soviet Union occurred in 1940 following the Molotov/Ribbentrop pact, and continues." European Parliament (13 January 1983). "Resolution on the situation in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania". Official Journal of the European Communities. C. 42/78. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ^ "After the German occupation in 1941–44, Estonia remained occupied by the Soviet Union until the restoration of its independence in 1991." Kolk and Kislyiy v. Estonia (European Court of Human Rights 17 January 2006), Text.

- ^ a b David James Smith, Estonia: independence and European integration, Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0415267285, p. xix

- ^ a b Parrott, Bruce (1995). "Reversing Soviet Military Occupation". State building and military power in Russia and the new states of Eurasia. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 112–115. ISBN 1563243601.

- ^ Van Elsuwege, Peter (April 2004). Russian-speaking minorities in Estonian and Latvia: Problems of integration at the threshold of the European Union (PDF). Flensburg Germany: European Centre for Minority Issues. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

The forcible incorporation of the Baltic states into the Soviet Union in 1940, on the basis of secret protocols to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, is considered to be null and void. Even though the Soviet Union occupied these countries for a period of fifty years, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania continued to exist as subjects of international law.

- ^ Zalimas, Dainius "Commentary to the Law of the Republic of Lithuania on Compensation of Damage Resulting from the Occupation of the USSR" – Baltic Yearbook of International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, ISBN 978-9004137462

- ^ a b cf. e.g. Boris Sokolov's article offering an overview Эстония и Прибалтика в составе СССР (1940–1991) в российской историографии Archived 2018-10-17 at the Wayback Machine (Estonia and the Baltic countries in the USSR (1940–1991) in Russian historiography). Accessed 30 January 2011.

- ^ Cole, Elizabeth A. (2007). Teaching the violent past: history education and reconciliation. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 233–234. ISBN 978-0742551435.

- ^ Combs, Dick (2008). Inside The Soviet Alternate Universe. Penn State Press. pp. 258, 259. ISBN 978-0271033556. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

The Putin administration has stubbornly refused to admit the fact of Soviet occupation of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia following World War II, although Putin has acknowledged that in 1989, during Gorbachev's reign, the Soviet parliament officially denounced the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, which led to the forcible incorporation of the three Baltic states into the Soviet Union.

- ^ Bugajski, Janusz (2004). Cold peace. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 109. ISBN 0275983625. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

Russian officials persistently claim that the Baltic states entered the USSR voluntarily and legally at the close of World War II and failed to acknowledge that Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were under Soviet occupation for fifty years.

- ^ МИД РФ: Запад признавал Прибалтику частью СССР Archived 29 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, grani.ru, May 2005

- ^ Комментарий Департамента информации и печати МИД России в отношении "непризнания" вступления прибалтийских республик в состав СССР Archived 2006-05-09 at the Wayback Machine, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Russia), 7 May 2005

- ^ Khudoley (2008), Soviet foreign policy during the Cold War, The Baltic factor, p. 90.

- ^ "How Russian Disinformation Targets the Former Soviet Bloc Around WWII Anniversaries - CHACR". 6 July 2020.

- ^ Zalimas, Dainius (1 January 2004). "Commentary to the Law of the Republic of Lithuania on Compensation of Damage Resulting from the Occupation of the USSR". Baltic Yearbook of International Law. 3. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: 97–164. doi:10.1163/221158903x00063. ISBN 978-9004137462.

- ^ Parliamentary Assembly (1996). "Opinion No. 193 (1996) on Russia's request for membership of the Council of Europe". Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ a b as described in Resolution 1455 (2005), Honouring of obligations and commitments by the Russian Federation Archived 2009-04-01 at the Wayback Machine, at the CoE Parliamentary site, retrieved December 6, 2009

- ^ Zalimas, Dainius (1 January 2004). "Commentary to the Law of the Republic of Lithuania on Compensation of Damage Resulting from the Occupation of the USSR". Baltic Yearbook of International Law. 3. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: 97–164. doi:10.1163/221158903x00063. ISBN 978-9004137462. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Treaty between the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic and the Republic of Lithuania on the Basis for Relations between States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011.

- ^ Van Elsuwgege, p378

- ^ For a legal evaluation of the annexation of the three Baltic states into the Soviet Union, see K. Marek, Identity and Continuity of States in Public International Law (1968), 383–91

- ^ D. Zalimas, Legal and Political Issues on the Continuity of the Republic of Lithuania, 1999, 4 Lithuanian Foreign Policy Review 111–12.

- ^ Torbakov, I. Russia and its neighbors. Warring histories and historical responsibility. FIIA Comment. Finnish Institute of International Affairs. 2010.

- ^ Gennady Charodeyev, Russia Rejects Latvia's Territorial Claim, Izvestia, (CDPSP, Vol XLIV, No 12.), 20 March 1992, p.3

- ^ James V. Wertsch (May 2008). "Blank Spots in Collective Memory: A Case Study of Russia". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 617: 61. JSTOR 25098013.

- ^ Gerner & Hedlund (1993). p. 60.

- ^ Gerner & Hedlund (1993). p. 62.

- ^ a b Andrew Roth (23 August 2019). "Molotov-Ribbentrop: why is Moscow trying to justify Nazi pact?: Exhibition about Soviet-Nazi treaty, signed on 23 August 1939, seeks to turn spotlight on west's behaviour in 1930s". The Guardian.

- ^ "Старые газеты : Библиотека : Пропагандист и агитатор РККА : №20, октябрь 1939г". www.oldgazette.org. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Rain Liivoja. "Competing Histories: Soviet War Crimes in the Baltic States". In Kevin Jon Heller; Gerry Simpson (eds.). The Hidden Histories of War Crimes Trials. Oxford University Press 2013. p. 249.

- ^ Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- ^ Soviet Information Bureau (1948). "Falsifiers of History (Historical Survey)". Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House: 50. 272848.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Soviet Information Bureau (1948). "Falsifiers of History (Historical Survey)". Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House: 52. 272848.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ According to Sīpols, "in mid-July 1940 elections took place [...]. In that way, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, that had been grabbed away from Russia as a result of foreign military intervention, joined her again, by the will of those peoples." – Сиполс В. Тайны дипломатические. Канун Великой Отечественной 1939–1941. Москва 1997. c. 242.

- ^ Новейшая история Отечества. XX век. Учебник для студентов вузов: в 2 т. /Под редакцией А.Ф. Киселева, Э.М. Щагина. М., 1998. c. 111

- ^ С.В.Черниченко "Об "оккупации" Прибалтики и нарушении прав русскоязычного населения" – "Международная жизнь" (август 2004 года) – "Статья С.в.черниченко*, Опубликованная В Журнале "Международная Жизнь" (Август 2004 Года) Под Заголовком "Об "Оккупации" Прибалтики И Наруше". Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ^ Олег Платонов. История русского народа в XX веке. Том 2. Available at http://lib.ru/PLATONOWO/russ3.txt Archived 21 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Khudoley (2008), Soviet foreign policy during the Cold War, The Baltic factor, pp. 56–73.

- ^ Žalimas, Dainius. Legal and Political Issues on the Continuity of the Republic of Lithuania Retrieved January 24, 2008. Archived April 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Opinion No. 193 (1996) on Russia's request for membership of the Council of Europe Archived 2011-05-07 at the Wayback Machine, at the CoE Parliamentary site, retrieved December 6, 2009

- ^ "Russia denies Baltic 'occupation'". 5 May 2005. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2007 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Bush denounces Soviet domination". 7 May 2005. Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2007 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ The term "occupation" inapplicable Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine Sergei Yastrzhembsky, May 2005.

- ^ Mendeloff, David A. (1968). Truth-telling and mythmaking in post-Soviet Russia: pernicious historical ideas, mass education, and interstate conflict (Thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. hdl:1721.1/17498.

- ^ Mendeloff, David (2002). "Causes and Consequences of Historical Amnesia – The annexation of the Baltic states in post-Soviet Russian popular history and political memory". In Kenneth, Christie (ed.). Historical injustice and democratic transition in eastern Asia and northern Europe: ghosts at the table of democracy. RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 79–118. ISBN 978-0700715992. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ http://web.ku.edu/~eceurope/communistnationssince1917/ch2.html Archived 1 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine at University of Kansas, retrieved January 23, 2008

- ^ Prof. Dr. G. von Rauch "Die Baltischen Staaten und Sowjetrussland 1919–1939", Europa Archiv No. 17 (1954), p. 6865.

Bibliography

edit- Aust, Anthony (2005). Handbook of International Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521530347.

- Bellamy, Chris (2007). Absolute War: Soviet Russia in the Second World War. Alfred a Knopf Inc. ISBN 978-0375410864.

- Brecher, Michael; Jonathan Wilkenfeld (1997). A Study of Crisis. University of Michigan Press. p. 596. ISBN 978-0472108060. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Frucht, Richard (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 132. ISBN 978-1576078006. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Gerner, Kristian; Hedlund, Stefan (1993). The Baltic States and the End of the Soviet Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415075701.

- Hiden, Johan; Salmon, Patrick (1994) [1991]. The Baltic Nations and Europe (Revised ed.). Harlow, England: Longman. ISBN 058225650X.

- Hiden, John (2008). Vahur Made; David J. Smith (eds.). The Baltic question during the Cold War. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415371001. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Mälksoo, Lauri (2003). Illegal Annexation and State Continuity: The Case of the Incorporation of the Baltic States by the USSR. M. Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9041121773. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- Marek, Krystyna (1968) [1954]. Identity and continuity of states in public international law (2 ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: Libr. Droz.

- McHugh, James; James S. Pacy (2001). Diplomats without a country: Baltic diplomacy, international law, and the Cold War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313318786. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Misiunas, Romuald J.; Taagepera, Rein (1993). The Baltic States, years of dependence, 1940–1990. University of California Press. ISBN 0520082281.

- O'Connor, Kevin (2003). The History of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 113–145. ISBN 978-0313323553. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Petrov, Pavel (2008). Punalipuline Balti Laevastik ja Eesti 1939–1941 (in Estonian). Tänapäev. ISBN 978-9985626313. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Plakans, Andrejs (2007). Experiencing Totalitarianism: The Invasion and Occupation of Latvia by the USSR and Nazi Germany 1939–1991. AuthorHouse. p. 596. ISBN 978-1434315731. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Rislakki, Jukka (2008). The Case for Latvia. Disinformation Campaigns Against a Small Nation. Rodopi. ISBN 978-9042024243. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Talmon, Stefan (1998). Recognition of governments in international law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198265733. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Tsygankov, Andrei P. (May 2009). Russophobia (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230614185.

- Wyman, David; Charles H. Rosenzveig (1996). The World Reacts to the Holocaust. JHU Press. pp. 365–381. ISBN 978-0801849695. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Ziemele, Ineta (2005). State Continuity and Nationality: The Baltic States and Russia. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9004142959.

Further reading

edit- Yaacov Falkov, "Between the Nazi Hammer and the Soviet Anvil: The Untold Story of the Red Guerrillas in the Baltic Region, 1941–1945", in Chris Murray (ed.), Unknown Conflicts of the Second World War: Forgotten Fronts (London: Routledge, 2019), pp. 96–119, ISBN 978-1138612945

- Aliide Naylor, The Shadow in the East

- Regarding the Procedure for carrying out the Deportation of Anti-Soviet Elements from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. – Full text, English

- The Global Museum on Communism about the occupation of Estonia by the Soviet Union.

- The Occupation museum of Latvia

- GULAG 113 – Canadian film about Estonians mobilized into the Red Army 1941 and forced into labour in the GULAG

- Soviet Aggression Against the Baltic States by (Latvian Supreme Court justice) Augusts Rumpeters — Short and thoroughly annotated dissertation on Soviet-Baltic treaties and relations. 1974. Full text

- Situation in Soviet occupied Estonia in 1955–1956. Manivald Räästas, Eduard Õun. 1956.

Academic and media articles

edit- Mälksoo, Lauri (2000). Professor Uluots, the Estonian Government in Exile and the Continuity of the Republic of Estonia in International Law. Nordic Journal of International Law 69.3, 289–316.

- Non-Recognition in the Courts: The Ships of the Baltic Republics by Herbert W. Briggs. In The American Journal of International Law Vol. 37, No. 4 (Oct., 1943), pp. 585–596.

- Alfred Erich Senn What Happened in Lithuania in 1940?(PDF)

- The Soviet Occupation of the Baltic States, by Irina Saburova. In Russian Review, 1955

- The Steel Curtain, Time Magazine, 14 April 1947

- The Iron Heel, Time Magazine, 14 December 1953

External links

edit- A radio drama about the occupation is presented in "John Alma Johnny and Myra Archived 11 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine", a presentation from Destination Freedom