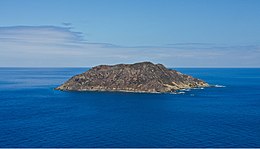

Desecheo (Spanish: Isla Desecheo) (Spanish pronunciation: [deseˈtʃeo]) is a small uninhabited island of the archipelago of Puerto Rico in the northeast of the Mona Passage; 13 mi (21 km) from the municipality of Rincón on the west coast (Punta Higüero) of the main island of Puerto Rico and 31 mi (50 km) northeast of Mona Island. It has a land area of 0.589 sq mi (377 acres; 153 ha; 1.53 km2). Politically, the island is administered by the U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as the Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, but part of the Sabanetas barrio of Mayagüez.

Isla Desecheo from Rincón | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 18°23′14″N 67°28′19″W / 18.38722°N 67.47194°W |

| Area | 1.524613 km2 (0.588656 sq mi) |

| Length | 1.8 km (1.12 mi) |

| Width | 1.1 km (0.68 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 218 m (715 ft) |

| Highest point | Sego Can Ridge |

| Administration | |

| Commonwealth | Puerto Rico |

| Municipio | Mayagüez |

| Barrio | Sabanetas |

Flora and fauna

editDesecheo, which has no known bodies of surface water, reaches a maximum elevation of 715 ft (218 m) and has an annual precipitation, on average, of 40.15 in (1020 mm). The lack of surface water limits its flora to thorny shrubs, small trees, weeds and various cacti, including the endangered higo chumbo (Harrisia portoricensis). Fauna includes various species of seabirds, three endemic species of lizard (Pholidoscelis desechensis, Anolis desechensis and Sphaerodactylus levinsi), introduced goats and rats, and a population of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) introduced from Cayo Santiago in 1967 as part of a study on adaptation. Before the introduction of rhesus monkeys the island was the largest nesting colony of the brown booby, however, no species presently nests on the island.

Geology

editAlthough politically part of Puerto Rico, along with the islands of Mona and Monito, Desecheo is not geologically related to the main island. It is believed that the island has been isolated, at least, since the Pliocene.[1] However, the island is part of the Rio Culebrinas formation which suggests that it was once connected to Puerto Rico.[2]

History

editNo evidence of Pre-Columbian human settlement of the island has been uncovered. Christopher Columbus was the first European to visit the island during his second voyage to the New World; however, it was not named until 1517 by Spanish explorer Nuñez Alvarez de Aragón.[3] During the 18th century the island was used by smugglers, pirates and bandits to hunt imported feral goats. During World War II, and until 1952, the island was used as a bombing range by the United States Armed Forces. From 1952 to 1964 the United States Air Force used Desecheo for survival training. In 1976 administration of the island was given to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and in 1983 it was designated as a National Wildlife Refuge. In 2000 it received a Marine reserve designation and fishing is allowed within 1/2-mile around the island.[4]

On May 12, 2022, 11 Haitian migrants died, 31 were rescued and others were feared missing, near Desecheo Island after their boat capsized on its way to Puerto Rico, from Haiti.[5]

Conservation and restoration

editIn the early 1900s, Desecheo NWR was still a major nesting ground for thousands of seabirds. Approximately 15,000 brown boobies, 2,000 red-footed boobies (Sula sula), 2,000 brown noddies (Anous stolidus), 1,500 bridled terns (Onychoprion anaethetus), and hundreds of magnificent frigatebirds (Fregata magnificens), laughing gulls (Larus atricilla), and sooty terns (Onychoprion fuscatus) nested here.[6]

Invasive mammals, including goats and rats, began to impact Desecheo NWR early in the 20th century. Around and during the time of World War II, the island was used as an artillery range by the US Air Force. That and the invasive species’ damage to Desecheo's ecosystem have been severe, and by the turn of the millennium, virtually no seabirds were using the refuge. [6] In response, in 2016 the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), Island Conservation, and other key partners, including the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), and Bell Laboratories and Tomcat, worked together to remove invasive black rats and Rhesus macaques from the island.[7][8][9][10]

One year later Desecheo Island was declared free of invasive species, and signs of recovery were observed, including Audubon's shearwaters sighted on the island for the first time and new bridled tern nests discovered. [11][6][12] In addition, 72 Federally protected Higo Chumbo cactus, (Harrisia portoricensis), were found and measured pre (2003–2010) and post eradication (2017). In 2017, individuals with flowers and huge yellow fruits were observed which is a good sign for the overall reproductive status of the population.[13][14]

Since 2018 social attraction equipment has been installed to augment bridled tern and brown noddy colonies and establish a species of conservation concern, the Audubon's shearwater.[15]

Diving

editBecause of a healthy reef and clear waters, with common visibility ranging from 98 to 148 feet (30 to 45 m), Desecheo is a very popular place for diving enthusiasts. Although diving is permitted around the island, the refuge is closed to the public due to the presence of unexploded military ordinances. Trespassers are subject to arrest by Federal law enforcement officers.

Amateur radio

editAs a separately administered area, under amateur radio rules Desecheo is considered a distinct "entity" for DXCC award purposes. Several DXpeditions have gone to the island, which has the ITU prefix KP5 (although since there is no permanent mailing address there the Federal Communications Commission does not actually grant this callsign). The Fish & Wildlife Service currently restricts such operations. The first approved DXpedition in fifteen years was allowed on the island between February 12 and 26, 2009, making 115,787 contacts.[16][17] Attempts to allow public access to Desecheo and the island of Navassa, which is located between Haiti and Jamaica, were made in the U.S. Congress, but the bill failed to reach the floor of the House of Representatives prior to the end of the 109th Congress, rendering the proposal dead.[18]

See also

editReferences

edit- Citations

- ^ Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer (July 1981). "Biogeography of the Puerto Rican Bank" (PDF). Atoll Research Bulletin. 251: 11. doi:10.5479/si.00775630.251.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2006.

- ^ "Desecheo Island Natural Reserve". UPR-Mayagüez Department of Biology Herbarium. Archived from the original on April 21, 2002. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ^ Desecheo – Welcome to Puerto Rico.org. Retrieved on August 14, 2006.

- ^ Guia Informativa para la Pesca Recreativa en Puerto Rico (aka, Reglamento de Pesca de Puerto Rico). Caribbeanfmc.com. Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico. Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales. Negociado de Pesca y Vida Silvestre. 3rd Edition. 2011. Appendix 2. Page 20. Accessed 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Eleven dead after Haitian migrant vessel capsizes near Puerto Rico". Reuters. May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c May 2, 2020 (June 27, 2017). "Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge safe from invasive mammals after nearly 100 years". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. US Fish & Wildlife.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ "Applying lessons learnt from tropical rodent eradications: a second attempt to remove invasive rats from Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico" (PDF). ISSG. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ "Rhesus macaque eradication to restore the ecological integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico". IUCN. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ "Restoring Wildlife Habitat on Desecheo Island". USFWS. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ "Desecheo Island Restoration Project". Island Conservation.

- ^ "Seabirds Return to Desecheo Island One Year After Restoration". Island Conservation. June 27, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "After Nearly a Century, Desecheo Wildlife can Thrive Again". Island Conservation. June 27, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ Figuerola-Hernández, CE; Swinnerton, K; Holmes, ND; Monsegur-Rivera, OA; Herrera-Giraldo, JL; Wolf, C; Hanson, C; Silander, S; Croll, DA (2017). "Resurgence of Harrisia portoricensis (Cactaceae) on Desecheo Island after the removal of invasive vertebrates: management implications". Endangered Species Research. 34: 339–347. doi:10.3354/esr00860. ISSN 1863-5407.

- ^ "The Threatened Higo Chumbo Cactus Resurges on Desecheo Island!". Island Conservation. November 29, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ Herrera-Giraldo, Jose-Luis; Figuerola-Hernández, Cielo E.; Wolf, Coral A.; Colón-Merced, Ricardo; Ventosa-Febles, Eduardo; Silander, Susan; Holmes, Nick D. (2021). "The use of social attraction techniques to restore seabird colonies on Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico". Ecological Solutions and Evidence. 2 (2). doi:10.1002/2688-8319.12058. ISSN 2688-8319.

- ^ "American Hams to Lead 2009 DXpedition to Desecheo Island". ARRL.org. October 10, 2008. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ "K5D – Desecheo Island 2009". KP5.us. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ "News / Updates". KP1-5.com. October 19, 2005. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- Other information