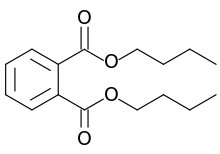

Dibutyl phthalate (DBP) is an organic compound which is commonly used as a plasticizer because of its low toxicity and wide liquid range. With the chemical formula C6H4(CO2C4H9)2, it is a colorless oil, although impurities often render commercial samples yellow.[3]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Dibutyl benzene-1,2-dicarboxylate | |

| Other names

Dibutyl phthalate

Di-n-butyl phthalate Butyl phthalate, dibasic (2:1) n-Butyl phthalate 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid dibutyl ester o-Benzenedicarboxylic acid dibutyl ester DBP Palatinol C Elaol Dibutyl 1,2-benzene-dicarboxylate | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 1914064 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.416 |

| EC Number |

|

| 262569 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C16H22O4 | |

| Molar mass | 278.348 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid |

| Odor | aromatic |

| Density | 1.05 g/cm3 at 20 °C |

| Melting point | −35 °C (−31 °F; 238 K) |

| Boiling point | 340 °C (644 °F; 613 K) |

| 13 mg/L (25 °C) | |

| log P | 4.72 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.00007 mmHg (20 °C)[1] |

| -175.1·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Pharmacology | |

| P03BX03 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

N), Harmful (Xi) |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H360Df, H400 | |

| P201, P202, P273, P281, P308+P313, P391, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 157 °C (315 °F; 430 K) (closed cup) |

| 402 °C (756 °F; 675 K) | |

| Explosive limits | 0.5 - 3.5% |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

5289 mg/kg (oral, mouse) 8000 mg/kg (oral, rat) 10,000 mg/kg (oral, guinea pig)[2] |

LC50 (median concentration)

|

4250 mg/m3 (rat) 25000 mg/m3 (mouse, 2 hr)[2] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 5 mg/m3[1] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 5 mg/m3[1] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

4000 mg/m3[1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Production and use

editDBP is produced by the reaction of n-butanol with phthalic anhydride.[3] DBP is an important plasticizer that enhances the utility of some major engineering plastics, such as PVC. Such modified PVC is widely used in plumbing for carrying sewerage and other corrosive materials.[3]

Degradation

editHydrolysis of DBP leads to phthalic acid and 1-butanol.[4] Monobutyl phthalate (MBP) is its major metabolite.[5]

Biodegradation

editBiodegradation by microorganisms represents one route for remediation of DBP. For example, Enterobacter species can biodegrade municipal solid waste—where the DBP concentration can be observed at 1500 ppm—with a half-life of 2–3 hours. In contrast, the same species can break down 100% of dimethyl phthalate after a span of six days.[6] The white rot fungus Polyporus brumalis degrades DBP.[7] DBP is leached from landfills.[8]

Physical properties relevant to biodegradation

editAs reflected by its octanol-water partition coefficient of around 4, it is lipophilic, which means that it is not readily mobilized (dissolved by) water. Nonetheless, dissolved organic compounds (DOC) increase its mobility in landfills.[9][10]

DBP has a low vapor pressure of 2.67 x 10−3 Pa. Thus DBP does not evaporate readily (hence its utility as a plasticizer).[11] The Henry's Law constant is 8.83 x 10−7 atm-m3/mol.[4]

Legislation

editDBP is regarded as an endocrine disruptor.[12]

European Union

editThe use of this substance in cosmetics, including nail polishes, is banned in the European Union under Directive 76/768/EEC 1976.[13]

The use of DBP has been restricted in the European Union for use in children's toys since 1999.[14]

An EU Risk Assessment has been conducted on DBP and the outcome has now been published in the EU Official Journal. To eliminate a potential risk to plants in the vicinity of processing sites and workers through inhalation, measures are to be taken within the framework of the IPPC Directive (96/61/EC) and the Occupational Exposure Directive (98/24/EC)[15] Also includes the 2004 addendum.

Based on urine samples from people of different ages, the European Commission Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks (SCHER) concluded that total exposures to DBP should be further reduced.[16]

Under European Union Directive 2011/65/EU [17] revision 2015/863,[18] DBP is limited to max 1000 ppm concentration in any homogenous material.

United States

editDibutyl phthalate (DBP) is one of the six phthalic acid esters found on the Priority Pollutant List, which consists of pollutants regulated by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA).[19]

DBP was added to the California Proposition 65 (1986) list of suspected teratogens in November 2006. It is a suspected endocrine disruptor.[12] It was used in many consumer products, e.g., nail polish, but such usages has declined since around 2006. It was banned in children's toys, in concentrations of 1000 ppm or greater, under section 108 of the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of 2008 (CPSIA).

Safety

editPhthalates are noncorrosive with low acute toxicity.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0187". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b "Dibutyl Phthalate". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c d Peter M. Lorz, Friedrich K. Towae, Walter Enke, Rudolf Jäckh, Naresh Bhargava, Wolfgang Hillesheim "Phthalic Acid and Derivatives" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a20_181.pub2

- ^ a b Huang, Jingyu; Nkrumah, Philip N.; Li, Yi; Appiah-Sefah, Gloria (2013). Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Volume 224. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. Vol. 224. Springer, New York, NY. pp. 39–52. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5882-1_2. ISBN 9781461458814. PMID 23232918.

- ^ Hu Y, Dong C, Chen M, Chen Y, Gu A, Xia Y, Sun H, Li Z, Wang Y (August 2015). "Effects of monobutyl phthalate on steroidogenesis through steroidogenic acute regulatory protein regulated by transcription factors in mouse Leydig tumor cells". J Endocrinol Invest. 38 (8): 875–84. doi:10.1007/s40618-015-0279-6. PMID 25903692. S2CID 21965989.

- ^ Abdel daiem, Mahmoud M.; Rivera-Utrilla, José; Ocampo-Pérez, Raúl; Méndez-Díaz, José D.; Sánchez-Polo, Manuel (2012). "Environmental impact of phthalic acid esters and their removal from water and sediments by different technologies – A review". Journal of Environmental Management. 109: 164–178. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.05.014. PMID 22796723.

- ^ Ishtiaq Ali, Muhammad (2011). Microbial degradation of polyvinyl chloride plastics (PDF) (PhD). Quaid-i-Azam University. p. 48. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Kjeldsen, Peter; Barlaz, Morton A.; Rooker, Alix P.; Baun, Anders; Ledin, Anna; Christensen, Thomas H. (1 October 2002). "Present and Long-Term Composition of MSW Landfill Leachate: A Review". Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 32 (4): 297–336. doi:10.1080/10643380290813462. ISSN 1064-3389. S2CID 53553742.

- ^ Christensen, Thomas H; Kjeldsen, Peter; Bjerg, Poul L; Jensen, Dorthe L; Christensen, Jette B; Baun, Anders; Albrechtsen, Hans-Jørgen; Heron, Gorm (2001). "Biogeochemistry of landfill leachate plumes". Applied Geochemistry. 16 (7–8): 659–718. Bibcode:2001ApGC...16..659C. doi:10.1016/s0883-2927(00)00082-2.

- ^ Bauer, M.J.; Herrmann, R. (2 July 2016). "Dissolved organic carbon as the main carrier of phthalic acid esters in municipal landfill leachates". Waste Management & Research. 16 (5): 446–454. doi:10.1177/0734242x9801600507. S2CID 98236129.

- ^ Donovan, Stephen F. (1996). "New method for estimating vapor pressure by the use of gas chromatography". Journal of Chromatography A. 749 (1–2): 123–129. doi:10.1016/0021-9673(96)00418-9.

- ^ a b "National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2021. doi:10.15620/cdc:105345. S2CID 241013949. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ EU Council Directive 76/768/EEC of 27 July 1976 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to cosmetic products

- ^ Ban of phthalates in childcare articles and toys, press release IP/99/829, 10 November 1999

- ^ "European Union Risk Assessment Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ "Phthalates in school supplies". GreenFacts Website. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ Directive 2011/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment Text with EEA relevance

- ^ Commission Delegated Directive (EU) 2015/863 of 31 March 2015 amending Annex II to Directive 2011/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the list of restricted substances

- ^ Gao, Da-Wen; Wen, Zhi-Dan (2016). "Phthalate esters in the environment: A critical review of their occurrence, biodegradation, and removal during wastewater treatment processes". Science of the Total Environment. 541: 986–1001. Bibcode:2016ScTEn.541..986G. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.09.148. PMID 26473701.