| Material | εr |

|---|---|

| Vacuum | 1 (by definition) |

| Air | 1.00058986±0.00000050 (at STP, 900 kHz),[1] |

| PTFE/Teflon | 2.1 |

| Polyethylene/XLPE | 2.25 |

| Polyimide | 3.4 |

| Polypropylene | 2.2–2.36 |

| Polystyrene | 2.4–2.7 |

| Carbon disulfide | 2.6 |

| BoPET | 3.1[2] |

| Paper, printing | 1.4[3] (200 kHz) |

| Electroactive polymers | 2–12 |

| Mica | 3–6[2] |

| Silicon dioxide | 3.9[4] |

| Sapphire | 8.9–11.1 (anisotropic)[5] |

| Concrete | 4.5 |

| Pyrex (glass) | 4.7 (3.7–10) |

| Neoprene | 6.7[2] |

| Natural rubber | 7 |

| Diamond | 5.5–10 |

| Salt | 3–15 |

| Melamine resin | 7.2–8.4[6] |

| Graphite | 10–15 |

| Silicone rubber | 2.9–4[7] |

| Silicon | 11.68 |

| GaAs | 12.4[8] |

| Silicon nitride | 7–8 (polycrystalline, 1 MHz)[9][10] |

| Ammonia | 26, 22, 20, 17 (−80, −40, 0, +20 °C) |

| Methanol | 30 |

| Ethylene glycol | 37 |

| Furfural | 42.0 |

| Glycerol | 41.2, 47, 42.5 (0, 20, 25 °C) |

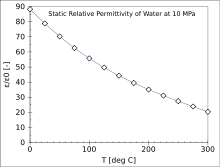

| Water | 87.9, 80.2, 55.5 (0, 20, 100 °C)[11] for visible light: 1.77 |

| Hydrofluoric acid | 175, 134, 111, 83.6 (−73, −42, −27, 0 °C), |

| Hydrazine | 52.0 (20 °C), |

| Formamide | 84.0 (20 °C) |

| Sulfuric acid | 84–100 (20–25 °C) |

| Hydrogen peroxide | 128 aqueous–60 (−30–25 °C) |

| Hydrocyanic acid | 158.0–2.3 (0–21 °C) |

| Titanium dioxide | 86–173 |

| Strontium titanate | 310 |

| Barium strontium titanate | 500 |

| Barium titanate[12] | 1200–10,000 (20–120 °C) |

| Lead zirconate titanate | 500–6000 |

| Conjugated polymers | 1.8–6 up to 100,000[13] |

| Calcium copper titanate | >250,000[14] |

The relative permittivity (in older texts, dielectric constant) is the permittivity of a material expressed as a ratio with the electric permittivity of a vacuum. A dielectric is an insulating material, and the dielectric constant of an insulator measures the ability of the insulator to store electric energy in an electrical field.

Permittivity is a material's property that affects the Coulomb force between two point charges in the material. Relative permittivity is the factor by which the electric field between the charges is decreased relative to vacuum.

Likewise, relative permittivity is the ratio of the capacitance of a capacitor using that material as a dielectric, compared with a similar capacitor that has vacuum as its dielectric. Relative permittivity is also commonly known as the dielectric constant, a term still used but deprecated by standards organizations in engineering[15] as well as in chemistry.[16]

Definition

editRelative permittivity is typically denoted as εr(ω) (sometimes κ, lowercase kappa) and is defined as

where ε(ω) is the complex frequency-dependent permittivity of the material, and ε0 is the vacuum permittivity.

Relative permittivity is a dimensionless number that is in general complex-valued; its real and imaginary parts are denoted as:[17]

The relative permittivity of a medium is related to its electric susceptibility, χe, as εr(ω) = 1 + χe.

In anisotropic media (such as non cubic crystals) the relative permittivity is a second rank tensor.

The relative permittivity of a material for a frequency of zero is known as its static relative permittivity.

Terminology

editThe historical term for the relative permittivity is dielectric constant. It is still commonly used, but has been deprecated by standards organizations,[15][16] because of its ambiguity, as some older reports used it for the absolute permittivity ε.[15][18][19] The permittivity may be quoted either as a static property or as a frequency-dependent variant, in which case it is also known as the dielectric function. It has also been used to refer to only the real component ε′r of the complex-valued relative permittivity.[citation needed]

Physics

editIn the causal theory of waves, permittivity is a complex quantity. The imaginary part corresponds to a phase shift of the polarization P relative to E and leads to the attenuation of electromagnetic waves passing through the medium. By definition, the linear relative permittivity of vacuum is equal to 1,[19] that is ε = ε0, although there are theoretical nonlinear quantum effects in vacuum that become non-negligible at high field strengths.[20]

The following table gives some typical values.

| Solvent | Relative permittivity | Temperature | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C6H6 | benzene | 2.3 | 298 K (25 °C) |

| Et2O | diethyl ether | 4.3 | 293 K (20 °C) |

| (CH2)4O | tetrahydrofuran (THF) | 7.6 | 298 K (25 °C) |

| CH2Cl2 | dichloromethane | 9.1 | 293 K (20 °C) |

| NH3(liq) | liquid ammonia | 17 | 273 K (0 °C) |

| C2H5OH | ethanol | 24.3 | 298 K (25 °C) |

| CH3OH | methanol | 32.7 | 298 K (25 °C) |

| CH3NO2 | nitromethane | 35.9 | 303 K (30 °C) |

| HCONMe2 | dimethyl formamide (DMF) | 36.7 | 298 K (25 °C) |

| CH3CN | acetonitrile | 37.5 | 293 K (20 °C) |

| H2O | water | 78.4 | 298 K (25 °C) |

| HCONH2 | formamide | 109 | 293 K (20 °C) |

The relative low frequency permittivity of ice is ~96 at −10.8 °C, falling to 3.15 at high frequency, which is independent of temperature.[21] It remains in the range 3.12–3.19 for frequencies between about 1 MHz and the far infrared region.[22]

Measurement

editThe relative static permittivity, εr, can be measured for static electric fields as follows: first the capacitance of a test capacitor, C0, is measured with vacuum between its plates. Then, using the same capacitor and distance between its plates, the capacitance C with a dielectric between the plates is measured. The relative permittivity can be then calculated as

For time-variant electromagnetic fields, this quantity becomes frequency-dependent. An indirect technique to calculate εr is conversion of radio frequency S-parameter measurement results. A description of frequently used S-parameter conversions for determination of the frequency-dependent εr of dielectrics can be found in this bibliographic source.[23] Alternatively, resonance based effects may be employed at fixed frequencies.[24]

Applications

editEnergy

editThe relative permittivity is an essential piece of information when designing capacitors, and in other circumstances where a material might be expected to introduce capacitance into a circuit. If a material with a high relative permittivity is placed in an electric field, the magnitude of that field will be measurably reduced within the volume of the dielectric. This fact is commonly used to increase the capacitance of a particular capacitor design. The layers beneath etched conductors in printed circuit boards (PCBs) also act as dielectrics.

Communication

editDielectrics are used in radio frequency (RF) transmission lines. In a coaxial cable, polyethylene can be used between the center conductor and outside shield. It can also be placed inside waveguides to form filters. Optical fibers are examples of dielectric waveguides. They consist of dielectric materials that are purposely doped with impurities so as to control the precise value of εr within the cross-section. This controls the refractive index of the material and therefore also the optical modes of transmission. However, in these cases it is technically the relative permittivity that matters, as they are not operated in the electrostatic limit.

Environment

editThe relative permittivity of air changes with temperature, humidity, and barometric pressure.[25] Sensors can be constructed to detect changes in capacitance caused by changes in the relative permittivity. Most of this change is due to effects of temperature and humidity as the barometric pressure is fairly stable. Using the capacitance change, along with the measured temperature, the relative humidity can be obtained using engineering formulas.

Chemistry

editThe relative static permittivity of a solvent is a relative measure of its chemical polarity. For example, water is very polar, and has a relative static permittivity of 80.10 at 20 °C while n-hexane is non-polar, and has a relative static permittivity of 1.89 at 20 °C.[26] This information is important when designing separation, sample preparation and chromatography techniques in analytical chemistry.

The correlation should, however, be treated with caution. For instance, dichloromethane has a value of εr of 9.08 (20 °C) and is rather poorly soluble in water (13 g/L or 9.8 mL/L at 20 °C); at the same time, tetrahydrofuran has its εr = 7.52 at 22 °C, but it is completely miscible with water. In the case of tetrahydrofuran, the oxygen atom can act as a hydrogen bond acceptor; whereas dichloromethane cannot form hydrogen bonds with water.

This is even more remarkable when comparing the εr values of acetic acid (6.2528)[27] and that of iodoethane (7.6177).[27] The large numerical value of εr is not surprising in the second case, as the iodine atom is easily polarizable; nevertheless, this does not imply that it is polar, too (electronic polarizability prevails over the orientational one in this case).

Lossy medium

editAgain, similar as for absolute permittivity, relative permittivity for lossy materials can be formulated as:

in terms of a "dielectric conductivity" σ (units S/m, siemens per meter), which "sums over all the dissipative effects of the material; it may represent an actual [electrical] conductivity caused by migrating charge carriers and it may also refer to an energy loss associated with the dispersion of ε′ [the real-valued permittivity]" ([17] p. 8). Expanding the angular frequency ω = 2πc / λ and the electric constant ε0 = 1 / μ0c2, which reduces to:

where λ is the wavelength, c is the speed of light in vacuum and κ = μ0c / 2π = 59.95849 Ω ≈ 60.0 Ω is a newly introduced constant (units ohms, or reciprocal siemens, such that σλκ = εr remains unitless).

Metals

editPermittivity is typically associated with dielectric materials, however metals are described as having an effective permittivity, with real relative permittivity equal to one.[28] In the high-frequency region, which extends from radio frequencies to the far infrared and terahertz region, the plasma frequency of the electron gas is much greater than the electromagnetic propagation frequency, so the refractive index n of a metal is very nearly a purely imaginary number. In the low frequency regime, the effective relative permittivity is also almost purely imaginary: It has a very large imaginary value related to the conductivity and a comparatively insignificant real-value.[29]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Hector, L. G.; Schultz, H. L. (1936). "The Dielectric Constant of Air at Radiofrequencies". Physics. 7 (4): 133–136. Bibcode:1936Physi...7..133H. doi:10.1063/1.1745374.

- ^ a b c Young, H. D.; Freedman, R. A.; Lewis, A. L. (2012). University Physics with Modern Physics (13th ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 801. ISBN 978-0-321-69686-1.

- ^ Borch, Jens; Lyne, M. Bruce; Mark, Richard E. (2001). Handbook of Physical Testing of Paper Vol. 2 (2 ed.). CRC Press. p. 348. ISBN 0203910494.

- ^ Gray, P. R.; Hurst, P. J.; Lewis, S. H.; Meyer, R. G. (2009). Analysis and Design of Analog Integrated Circuits (5th ed.). Wiley. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-470-24599-6.

- ^ Harman, A. K.; Ninomiya, S.; Adachi, S. (1994). "Optical constants of sapphire (α‐Al2O3) single crystals". Journal of Applied Physics. 76 (12): 8032–8036. Bibcode:1994JAP....76.8032H. doi:10.1063/1.357922.

- ^ "Dielectric Materials—The Dielectric Constant". Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ "Properties of silicone rubber". Azo Materials.

- ^ Fox, Mark (2010). Optical Properties of Solids (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0199573370.

- ^ "Fine Ceramics" (PDF). Toshiba Materials.

- ^ "Material Properties Charts" (PDF). Ceramic Industry. 2013.

- ^ Archer, G. G.; Wang, P. (1990). "The Dielectric Constant of Water and Debye-Hückel Limiting Law Slopes". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 19 (2): 371–411. doi:10.1063/1.555853.

- ^ "Permittivity". schools.matter.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11.

- ^ Pohl, H. A. (1986). "Giant polarization in high polymers". Journal of Electronic Materials. 15 (4): 201. Bibcode:1986JEMat..15..201P. doi:10.1007/BF02659632.

- ^ Guillemet-Fritsch, S.; Lebey, T.; Boulos, M.; Durand, B. (2006). "Dielectric properties of CaCu3Ti4O12 based multiphased ceramics" (PDF). Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 26 (7): 1245. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2005.01.055.

- ^ a b c IEEE Standards Board (1997). "IEEE Standard Definitions of Terms for Radio Wave Propagation". IEEE STD 211-1997: 6.

- ^ a b Braslavsky, S.E. (2007). "Glossary of terms used in photochemistry (IUPAC recommendations 2006)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 79 (3): 293–465. doi:10.1351/pac200779030293. S2CID 96601716.

- ^ a b Linfeng Chen & Vijay K. Varadan (2004). Microwave electronics: measurement and materials characterization. John Wiley and Sons. p. 8, eq.(1.15). doi:10.1002/0470020466. ISBN 978-0-470-84492-2.

- ^ King, Ronold W. P. (1963). Fundamental Electromagnetic Theory. New York: Dover. p. 139.

- ^ a b John David Jackson (1998). Classical Electrodynamics (Third ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-471-30932-1.

- ^ Mourou, Gerard A. (2006). "Optics in the relativistic regime". Reviews of Modern Physics. 78 (2): 309. Bibcode:2006RvMP...78..309M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.78.309.

- ^ Evans, S. (1965). "Dielectric Properties of Ice and Snow–a Review". Journal of Glaciology. 5 (42): 773–792. doi:10.3189/S0022143000018840. S2CID 227325642.

- ^ Fujita, Shuji; Matsuoka, Takeshi; Ishida, Toshihiro; Matsuoka, Kenichi; Mae, Shinji, A summary of the complex dielectric permittivity of ice in the megahertz range and its applications for radar sounding of polar ice sheets (PDF)

- ^ Kuek, CheeYaw. "Measurement of Dielectric Material Properties" (PDF). R&S.

- ^ Costa, F.; Amabile, C.; Monorchio, A.; Prati, E. (2011). "Waveguide Dielectric Permittivity Measurement Technique Based on Resonant FSS Filters". IEEE Microwave and Wireless Components Letters. 21 (5): 273. doi:10.1109/LMWC.2011.2122303. S2CID 34515302.

- ^ 5×10−6/°C, 1.4×10−6/%RH and 100×10−6/atm respectively. See A Low Cost Integrated Interface for Capacitive Sensors, Ali Heidary, 2010, Thesis, p. 12. ISBN 9789461130136.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ a b AE. Frisch, M. J. Frish, F. R. Clemente, G. W. Trucks. Gaussian 09 User's Reference. Gaussian, Inc.: Walligford, CT, 2009.- p. 257.

- ^ Lourtioz, J.-M.; et al. (2005). Photonic Crystals: Towards Nanoscale Photonic Devices. Springer. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-3-540-24431-8. equation (4.6), page 121

- ^ Lourtioz (2005), equations (4.8)–(4.9), page 122