50°50′11″N 0°46′51″W / 50.8363°N 0.7808°W

Diocese of Chichester Dioecesis Cicestrensis | |

|---|---|

Nave of Chichester Cathedral | |

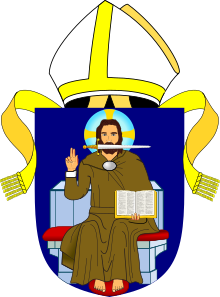

Coat of arms | |

| Location | |

| Ecclesiastical province | Canterbury |

| Archdeaconries | Chichester, Horsham, Hastings, Brighton & Lewes |

| Statistics | |

| Parishes | 365 |

| Churches | 500 |

| Information | |

| Cathedral | Chichester Cathedral (1075–present) Selsey Abbey (681–1075) |

| Language | English |

| Current leadership | |

| Bishop | Martin Warner |

| Suffragans | Ruth Bushyager, Bishop of Horsham Will Hazlewood, Bishop of Lewes |

| Archdeacons | Martin Lloyd Williams, Archdeacon of Brighton & Lewes Edward Dowler, Archdeacon of Hastings Luke Irvine-Capel, Archdeacon of Chichester Angela Martin, Archdeacon of Horsham |

| Website | |

| chichester.anglican.org | |

The Diocese of Chichester is a Church of England diocese based in Chichester, covering Sussex. It was founded in 681 as the ancient Diocese of Selsey, which was based at Selsey Abbey, until the see was translated to Chichester in 1075. The cathedral is Chichester Cathedral and the diocesan bishop is the Bishop of Chichester. The diocese is in the Province of Canterbury.

Organisation

editThe Bishop of Chichester has overall episcopal oversight of the diocese, with certain responsibilities delegated to the Bishop of Horsham and the Bishop of Lewes. The suffragan See of Lewes was created in 1909 and was the suffragan bishop for the whole diocese until the See of Horsham was created in 1968.

The four archdeaconries of the diocese are Chichester, Horsham, Hastings and Brighton & Lewes. Until 2014, the Archdeaconry of Chichester covered the coastal region of West Sussex along with Brighton and Hove, the Archdeaconry of Horsham the remainder of West Sussex and the Archdeaconry of Lewes & Hastings covered East Sussex.[1]

On 12 May 2014, it was announced that the diocese is to take forward proposals to create a fourth archdeaconry (initially referred to as Brighton.)[2] Since Lewes itself would be within the new archdeaconry, Lewes & Hastings archdeaconry would become simply Hastings archdeaconry.[3] On 8 August 2014, the Church Times reported that the archdeaconry of Brighton & Lewes had been created and Hastings archdeaconry renamed.[4] On 12 October 2014, it was announced that, from 2015, Martin Lloyd Williams would become the first Archdeacon of Brighton & Lewes.[5]

The 21 deaneries of the diocese are:

| Diocese | Archdeaconries | Rural Deaneries |

|---|---|---|

| Diocese of Chichester | Archdeaconry of Chichester | Deanery of Arundel and Bognor |

| Deanery of Chichester | ||

| Deanery of Westbourne | ||

| Deanery of Worthing | ||

| Archdeaconry of Brighton & Lewes | Deanery of Brighton | |

| Deanery of Hove | ||

| Deanery of Lewes and Seaford | ||

| Archdeaconry of Hastings | Deanery of Battle and Bexhill | |

| Deanery of Dallington | ||

| Deanery of Eastbourne | ||

| Deanery of Hastings | ||

| Deanery of Rotherfield | ||

| Deanery of Rye | ||

| Deanery of Uckfield | ||

| Archdeaconry of Horsham | Deanery of Cuckfield | |

| Deanery of East Grinstead | ||

| Deanery of Horsham | ||

| Deanery of Hurst | ||

| Deanery of Midhurst | ||

| Deanery of Petworth | ||

| Deanery of Storrington |

Bishops

editAlongside the diocesan Bishop of Chichester (Martin Warner), the diocese has two suffragan bishops: a Bishop of Horsham (Ruth Bushyager) and Bishop of Lewes (Will Hazlewood). The Bishop of Horsham oversees the archdeaconries of Chichester and Horsham, while the Bishop of Lewes oversees the archdeaconries of Brighton & Lewes and Hastings.

Other bishops living in the diocese are licensed as honorary assistant bishops:

- 1992–present: Michael Marshall, former suffragan Bishop of Woolwich, lives outside the diocese, in Chelsea, London.[6]

- 1995–present: David Wilcox, retired suffragan Bishop of Dorking, lives in Willingdon.[7]

- 2005–present: Ken Barham, retired diocesan Bishop of Cyangugu, Rwanda, lives in Battle.[8]

- 2009–present: Christopher Herbert, retired diocesan Bishop of St Albans, lives outside the diocese, in Wrecclesham, Surrey.[9]

- 2010–present: Henry Scriven, Mission Director for Latin America (CMS) and former Assistant Bishop in Pittsburgh and Suffragan Bishop in Europe, lives in Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire and is also licensed in Oxford and Winchester dioceses.[10]

- 2011–present: Alan Chesters, retired diocesan Bishop of Blackburn, lives in Chichester, West Sussex.[11]

- 2011–present: Laurie Green, former area Bishop of Bradwell, retired to Bexhill-on-Sea.[12]

Three further bishops retired to West Sussex in 2013: Michael Langrish, former diocesan Bishop of Exeter, moved to Walberton;[13] Christopher Morgan, former area Bishop of Colchester, lives in Worthing;[14] and Geoffrey Rowell, retired Bishop in Europe and Bishop suffragan of Basingstoke, lived in Chichester until his death in 2017.[15]

There is no alternative episcopal oversight (for parishes in the diocese which reject the ministry of priests who are women) in the diocese because the ordinary (Martin Warner) does not ordain women as priests.

Episcopal areas

editFrom 1974[16] until 2013 (by area scheme from 1984 onwards),[17] episcopal oversight of the diocese was divided: the Bishop of Chichester retained direct oversight of a coastal area including the See city and Brighton, and delegated Ordinary authority for the rest of West and East Sussex to the area Bishops of Horsham and of Lewes respectively.[16]

History

editChristianity was introduced to the British Isles during the Roman occupation. When the Romans departed, there were waves of non-Christian invasions from northern Europe; these were mainly Angles, Saxons and Jutes. Celtic Christianity was driven, with the Celts, into the remote western parts of the islands. The south of England was settled by Saxons. After the invasions had finished, Roman missionaries evangelized the south east of England and Celtic missionaries the rest of the British Isles.[18]

The Kingdom of Sussex remained steadfastly non-Christian until the arrival of Saint Wilfrid in 681 AD.[18] Wilfrid built his cathedral church in Selsey and dedicated it to Saint Peter. The original structure would have been made largely of wood. The stones from the old cathedral would have been used in the later church.[18] Some stonework discovered in a local garden wall was believed to have come from the palm cross that stood outside the original cathedral and is now integrated into the war memorial that is in the perimeter wall outside the church.[18]

The cathedral founded at Selsey was probably built, where the chancel of the old church still remains, at Church Norton.[19] Selsey Abbey was the first seat of the South Saxon see. The seat was moved to Chichester in 1075 under William the Conqueror.[18]

Insignia and shield of the diocese

editOne of the earliest representations of the diocesan coat of arms is that on the seal of Bishop Ralph Neville (1224–1243). A similar representation appears on the seal of his successor, St Richard (1244–1253).[20] In heraldic language the arms are blazoned as follows:

Azure a representation of Our Saviour seated crowned and a glory round His head, His right hand raised in benediction, His left resting on an open book Or, in His mouth a sword fessewise, point to the sinister Gules.[21]

as follows

Most of the older English cathedrals have arms of a simple design, usually various combinations of crosses, swords, keys and so on. Our Lady and the Holy Child are however shown in the top third of Lincoln’s shield and occupy the whole of Salisbury’s shield. Excluding the diocese of Sodor and Man, which was linked with Denmark prior to 1546, Chichester is the only other old diocese which includes a human figure in its arms. Over the centuries identifying the figure has attracted some unusual theories. The most common misconception, which was still being repeated in 1894, was that the arms show "Presbyter John sitting on a tombstone".[20] Presbyter John, or "Prester John" as he is more commonly known, was a figure of mediaeval fantasy who appeared in many books and travellers tales. It was said that he was an all-powerful and immensely rich Christian emperor who lived in the East or in Africa and who would come to the aid of crusaders. A letter circulated in Europe in about 1165 referred to the annual visit of Prester John and his army, complete with chariots and elephants, to the tomb of the prophet Daniel in Babylonia Deserta. It was the imagery of this letter that seems to have become attached to Chichester’s diocesan coat of arms.[20]

Much more likely is that the imagery is parallel to that seen in an early fourteenth-century manuscript of the Apocalypse of St John. This illustrates several passages with a figure who variously has a sword across his mouth, holds an open book, and is seated on a throne. The clearest illustration accompanies chapter 19, verses 11-16:

I saw heaven standing open and there before me was a white horse, whose rider is called Faithful and True. With justice he judges and makes war. His eyes are like blazing fire, and on his head are many crowns. He has a name written on him that no-one knows but he himself. He is dressed in a robe dipped in blood, and his name is the Word of God. The armies of heaven were following him, riding on white horses and dressed in fine linen, white and clean. Out of his mouth comes a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations. "He will rule them with an iron sceptre." He treads the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has this name written: King of kings and Lord of Lords.[20]

In this manuscript are to be seen the main elements of the diocesan coat of arms and there is thus tangible support for what common sense suggests — that the figure is that of our Lord as ruler of the nations. The image was common in Byzantine iconography as Christ the Pantocrator.[20]

In 1626 Thomas Vicars, vicar of Cuckfield, wrote in a sermon which he illustrated with references to the book of Revelation and also to Hebrews chapter 4 verse 12, "For the word of God is living and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart." He dedicated his sermon to his father-in-law, the then Bishop of Chichester:

The subject of the sermon is your Coate of Armes. The most godly and fairest Armes that ever I or any in the world set his eyes upon. Christ Jesus the great Pastor and Bishop of our soules sits in your azure field in a faire long garment of beaten gold, with a sharpe two- edged sword in his mouth. Is it accounted a great grace, and that for Kings and Princes too, to carrie in their shields, a Lyon, an Eagle, a Lilly, a Harpe or such-like animal or artificial thing? How much more honour is it then I pray you to carrie Christ Jesus in your shield, who is Lord of Lords and King of Kings?[20]

The position of the sword in the diocesan coat of arms is a matter that has raised some questions. In the newly drawn coat of arms the sword has been placed across the mouth, whereas previously and in the cathedral’s coat of arms the sword is placed to the right of the mouth. It seems likely that medieval versions had the former position, while later generations have preferred the latter.[20]

A medieval window in Bourges cathedral, France, depicts Christ with seven seals in his right hand and seven stars in his left. The sword is clearly across his mouth, as it is in the depiction of the same scene on the great Apocalypse tapestry in the chateau at Angers, also in France. In both of these representations, however, the sword points to the viewer’s left, the opposite way from the diocesan arms.[20]

Safeguarding

editIn 2011 the Archbishop of Canterbury appointed an inquiry into long-running child protection problems in the diocese. The interim inquiry report found that there had been "an appalling history" over two decades of child protection problems and that many children had suffered hurt and damage. Because of concerns that safeguarding still remained dysfunctional, Lambeth Palace took over the oversight of clergy appointments and the protection of children and vulnerable adults in the diocese.[22][23] Previously Baroness Butler-Sloss had carried out a review of historic child sex abuse problems that had led to the conviction of a priest in 2008.[24]

On 13 November 2012 two former clergy of the diocese, including the former Bishop of Lewes, Peter Ball, were arrested by police investigating allegations of child sex abuse in the 1980s and 1990s. The arrests followed the submission of reports by a safeguarding consultant from Lambeth Palace to the police.[25] A trial date of 5 October 2015 was set for Ball and former Brighton priest Vickery House.[26] Ball was later sentenced to prison for offences against adult men but the child abuse charges were left on file. Vickery House was convicted of sex offences in the 1970s and 1980s against a boy and three men, and jailed for six and a half years.[27][28]

On 5 April 2013, Hove Crown Court convicted Michael Mytton and the Revd Keith Wilkie Denford of sexually assaulting boys between 1987 and 1994 when they had been at St John the Evangelist's Church, Burgess Hill in the Chichester diocese; Mytton as organist and Denford as vicar.[29] St John the Evangelist's had employed Mytton despite his having been forced to leave a parish in Uckfield in 1981 because he was convicted of committing two acts of gross indecency with a 12-year-old boy.[29][30] Denford was jailed for 18 months and Mytton was given a suspended jail term.[31]

In July 2013, following a ruling by the General Synod, the Church of England formally apologised for past child abuse and the church's failure to prevent it.[32][33]

In December 2013 a 56-year-old retired priest in the diocese was arrested on suspicion of indecency, indecent assault and cruelty in 1988 and 1989.[34][35] In April 2015 Jonathan Graves was charged with indecent assault against a boy and two women, and child cruelty against the same boy.[36]

On 12 June 2015, Hove Crown Court convicted retired priest Robert Coles of sex offences against a young boy about 40 years ago. He was already serving an eight-year sentence for sex offences against three other young boys in West Sussex, between 31 and 38 years ago, and an additional sixteen months sentence was added.[37]

References

edit- ^ "Diocese of Chichester – Archdeacons". Diocese of Chichester. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Diocese of Chichester – Announcement of a Fourth Archdeaconry for the Diocese of Chichester Archived 14 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed 14 May 2014)

- ^ Diocese of Chichester – Suffragan Bishop of Lewes: Statement of Needs Archived 14 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine p. 7 (Accessed 14 May 2014)

- ^ "Appointments". Church Times. No. 7899. 8 August 2014. p. 24. ISSN 0009-658X. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Diocese of Chichester – New Archdeacon of Brighton and Lewes announced Archived 19 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed 12 October 2014)

- ^ "Michael Eric Marshall". Crockford's Clerical Directory (online ed.). Church House Publishing. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "David Peter Wilcox". Crockford's Clerical Directory (online ed.). Church House Publishing. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Kenneth Lawrence Barham". Crockford's Clerical Directory (online ed.). Church House Publishing. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Christopher William Herbert". Crockford's Clerical Directory (online ed.). Church House Publishing. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Scriven, Henry William". Who's Who. Vol. 2014 (December 2013 online ed.). A & C Black. Retrieved 30 April 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Alan David Chesters". Crockford's Clerical Directory (online ed.). Church House Publishing. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Laurence Alexander Green". Crockford's Clerical Directory (online ed.). Church House Publishing. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Michael Laurence Langrish". Crockford's Clerical Directory (online ed.). Church House Publishing. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Christopher Heudebourck Morgan". Crockford's Clerical Directory (online ed.). Church House Publishing. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Rowell, (Douglas) Geoffrey". Who's Who. Vol. 2014 (December 2013 online ed.). A & C Black. Retrieved 23 August 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b "Episcopal areas for Chichester". Church Times. No. 5829. 1 November 1974. p. 24. ISSN 0009-658X. Retrieved 27 August 2019 – via UK Press Online archives.

- ^ "4: The Dioceses Commission, 1978–2002" (PDF). Church of England. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Diocese of South Saxons". Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Tatton-Brown.Chichester Cathedral:The Medieval Fabric. p.25

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Insignia and shield of the Diocese". Diocese of Chichester. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ^ Townend, Peter, ed. (1963). Burke's Peerage (103rd ed.). Burke's Peerage Limited. p. 2650.

- ^ Batty, David (31 August 2012). "Child sex abuse inquiry damns Chichester church's local safeguarding". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Williams, Rowan (30 August 2012). "Archbishop's Chichester Visitation — interim report published". Church of England. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Church of England criticised over Sussex sex abuse". BBC. 25 May 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Pugh, Tom (13 November 2012). "Retired bishop Peter Ball held in child sex abuse investigation". The Independent. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Frank Le Duc (20 January 2015). "Date set for retired bishop and fellow former Brighton priest to face child sex abuse trial". Brighton and Hove News. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ "Vickery House found guilty of historic sex offences". BBC News. 27 October 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ "Vickery House: Priest jailed over sex attacks". BBC News. 29 October 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ a b Pugh, Tom (5 April 2013). "Ex-Church of England priest Keith Wilkie Denford and organist Michael Mytton guilty of string of child abuse offences". The Independent. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Latest Safeguarding news

- ^ "Father Keith Wilkie Denford jailed over child sex abuse". BBC. 9 May 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ "Church of England makes Chichester child abuse apology". BBC. 7 July 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Bishop John Gladwin and Chancellor Rupert Bursell QC (3 May 2013). Archbishop's Chichester Visitation — final report (PDF) (Report). Church of England. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ "Sussex priest bailed over child sex abuse". BBC. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ "Eastbourne priest arrested on sex charges". Eastbourne Herald. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ "Former priest Jonathan Graves charged with sex attack on boy". BBC News. 15 April 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ "Retired Eastbourne priest receives further prison sentence for historic sex offences". Eastbourne Herald. 12 June 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

Sources

edit- "Diocese of South Saxons". Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- "Church of England Statistics 2002". Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- "Diocese of Chichester Website". Diocese of Chichester. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "A Church Near You". Church of England. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Tatton-Brown, Tim (1994). Mary Hobbs (ed.). The Medieval Fabric in Chichester Cathedral: An Historic Survey. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-924-3.