Diphenhydramine (DPH) is an antihistamine and sedative first developed by George Rieveschl and put into commercial use in 1946.[11][12] It is available as a generic medication,[13] and also sold under the brand name Benadryl among others.[13] In 2021, it was the 242nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[14][15]

It is a first-generation H1-antihistamine and it works by blocking certain effects of histamine, which produces its antihistamine and sedative effects.[13][2] Diphenhydramine is also a potent anticholinergic, which means it also works as a deliriant at much higher than recommended doses as a result.[16]

It is mainly used to treat allergies, insomnia, and symptoms of the common cold. It is also less commonly used for tremors in parkinsonism, and nausea.[13] It is taken by mouth, injected into a vein, injected into a muscle, or applied to the skin.[13] Maximal effect is typically around two hours after a dose, and effects can last for up to seven hours.[13]

Common side effects include sleepiness, poor coordination, and upset stomach.[13] Its use is not recommended in young children or the elderly.[13][17] There is no clear risk of harm when used during pregnancy; however, use during breastfeeding is not recommended.[18]

Its sedative and deliriant effects have led to some cases of recreational use.[19][2]

History

editIn 1943, diphenhydramine was discovered by chemist George Rieveschl and one of his students, Fred Huber, while they were conducting research into muscle relaxants at the University of Cincinnati.[20] Huber first synthesized diphenhydramine. Rieveschl then worked with Parke-Davis to test the compound, and the company licensed the patent from him.[21] In 1946, it became the first prescription antihistamine approved by the U.S. FDA.[22]

In the 1960s, diphenhydramine was found to weakly inhibit reuptake of the neurotransmitter serotonin.[23] This discovery led to a search for viable antidepressants with similar structures and fewer side effects, culminating in the invention of fluoxetine (Prozac), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).[23][24] A similar search had previously led to the synthesis of the first SSRI, zimelidine, from brompheniramine, also an antihistamine.[25]

In 1975, diphenhydramine was still available only by prescription in the U.S. and required medical supervision.[26]

Medical uses

editDiphenhydramine is a first-generation antihistamine used to treat a number of conditions including allergic symptoms and itchiness, the common cold, insomnia, motion sickness, and extrapyramidal symptoms.[27][28] Diphenhydramine also has local anesthetic properties, and has been used as such in people allergic to common local anesthetics such as lidocaine.[29]

Allergies

editDiphenhydramine is effective in treatment of allergies.[30] As of 2007[update], it was the most commonly used antihistamine for acute allergic reactions in the emergency department.[31]

By injection it is often used in addition to epinephrine for anaphylaxis,[32] although as of 2007[update] its use for this purpose had not been properly studied.[33] Its use is only recommended once acute symptoms have improved.[30]

Topical formulations of diphenhydramine are available, including creams, lotions, gels, sprays and eye drops. These are used to relieve itching and have the advantage of causing fewer systemic effects (e.g., drowsiness) than oral forms.[34]

Movement disorders

editDiphenhydramine is used to treat akathisia and parkinsonism caused by antipsychotics.[35] It is also used to treat acute dystonia including torticollis and oculogyric crisis caused by typical antipsychotics.

Sleep

editBecause of its sedative properties, diphenhydramine is widely used in nonprescription sleep aids for insomnia. The drug is an ingredient in several products sold as sleep aids, either alone or in combination with other ingredients such as acetaminophen (paracetamol) in Tylenol PM and ibuprofen in Advil PM. Diphenhydramine can cause minor psychological dependence.[36] Diphenhydramine has also been used as an anxiolytic.[37]

Diphenhydramine has also been used off-prescription by parents in an attempt to make their children sleep and to sedate them on long-distance flights.[38] This has been met with criticism, both by doctors and by members of the airline industry, because sedating passengers may put them at risk if they cannot react efficiently to emergencies,[39] and because the drug's side effects, especially the chance of a paradoxical reaction, may make some users hyperactive. Addressing such use, the Seattle Children's hospital argued, in a 2009 article, "Using a medication for your convenience is never an indication for medication in a child."[40]

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine's 2017 clinical practice guidelines recommended against the use of diphenhydramine in the treatment of insomnia, because of poor effectiveness and low quality of evidence.[41] A major systematic review and network meta-analysis of medications for the treatment of insomnia published in 2022 found little evidence to inform the use of diphenhydramine for insomnia.[42]

Nausea

editDiphenhydramine also has antiemetic properties, which make it useful in treating the nausea that occurs in vertigo and motion sickness. However, when taken above recommended doses, it can cause nausea (especially above 200 mg).[43]

Special populations

editDiphenhydramine is not recommended for people older than 60 and children younger than six, unless a physician is consulted.[13][17][44] These people should be treated with second-generation antihistamines, such as loratadine, desloratadine, fexofenadine, cetirizine, levocetirizine, and azelastine.[45] Because of its strong anticholinergic effects, diphenhydramine is on the Beers list of drugs to avoid in the elderly.[46][47]

Diphenhydramine is excreted in breast milk.[48] It is expected that low doses of diphenhydramine taken occasionally will cause no adverse effects in breastfed infants. Large doses and long-term use may affect the baby or reduce breast milk supply, especially when combined with sympathomimetic drugs, such as pseudoephedrine, or before the establishment of lactation. A single bedtime dose after the last feeding of the day may minimize harmful effects of the medication on the baby and on the milk supply. Still, non-sedating antihistamines are preferred.[49]

Paradoxical reactions to diphenhydramine have been documented, particularly in children, and it may cause excitation instead of sedation.[50]

Topical diphenhydramine is sometimes used especially for people in hospice. This use is without indication and topical diphenhydramine should not be used as treatment for nausea because research has not shown that this therapy is more effective than others.[51]

There were no documented cases of clinically apparent acute liver injury caused by normal doses of diphenhydramine.[52]

Anxiety

editDiphenhydramine (as Benadryl) is not typically used to treat anxiety because its long-term use may cause adverse effects, such as memory loss, especially in the elderly.[53] Benadryl is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating anxiety.[53]

Adverse effects

editThe most prominent side effects are dizziness and sleepiness.[54] A typical dose creates driving impairment equivalent to a blood-alcohol level of 0.10, which is higher than the 0.08 limit of most drunk-driving laws.[31]

Diphenhydramine is a potent anticholinergic agent and potential deliriant in higher doses. This activity is responsible for the side effects of dry mouth and throat, increased heart rate, pupil dilation, urinary retention, constipation, and, at high doses, hallucinations or delirium. Other side effects include motor impairment (ataxia), flushed skin, blurred vision at nearpoint owing to lack of accommodation (cycloplegia), abnormal sensitivity to bright light (photophobia), sedation, difficulty concentrating, short-term memory loss, visual disturbances, irregular breathing, dizziness, irritability, itchy skin, confusion, increased body temperature (in general, in the hands and/or feet), temporary erectile dysfunction, and excitability, and although it can be used to treat nausea, higher doses may cause vomiting.[54] Diphenhydramine in overdose may occasionally result in QT prolongation.[55]

Some individuals experience an allergic reaction to diphenhydramine in the form of hives.[56][57]

Conditions such as restlessness or akathisia can worsen from increased levels of diphenhydramine, especially with recreational dosages.[50] Normal doses of diphenhydramine, like other first generation antihistamines, can also make symptoms of restless legs syndrome worse.[58] As diphenhydramine is extensively metabolized by the liver, caution should be exercised when giving the drug to individuals with hepatic impairment.

Anticholinergic use later in life is associated with an increased risk for cognitive decline and dementia among older people.[59] Drowsiness, memory loss, confusion, dry mouth or constipation may also occur in elderly people.[53]

Contraindications

editDiphenhydramine is contraindicated in premature infants and neonates, as well as people who are breastfeeding. It is a pregnancy Category B drug. Diphenhydramine has additive effects with alcohol and other CNS depressants. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors prolong and intensify the anticholinergic effect of antihistamines.[60]

Overdose

editDiphenhydramine is one of the most commonly misused over-the-counter drugs in the United States.[61] In cases of extreme overdose, if not treated in time, acute diphenhydramine poisoning may have serious and potentially fatal consequences. Overdose symptoms may include:[62]

- Abdominal pain

- Abnormal speech (inaudibility, forced speech, etc.)

- Acute megacolon

- Anxiety/nervousness

- Coma

- Delirium

- Disorientation

- Dissociation

- Euphoria or dysphoria

- Extreme drowsiness

- Flushed skin

- Hallucinations (auditory, visual, tactile, etc.)

- Heart palpitations

- Inability to urinate

- Motor disturbances

- Muscle spasms

- Seizures

- Severe dizziness

- Severe mouth and throat dryness

- Tremors

- Vomiting

Acute poisoning can be fatal, leading to cardiovascular collapse and death in 2–18 hours, and in general is treated using a symptomatic and supportive approach.[45] Diagnosis of toxicity is based on history and clinical presentation, and in general precise plasma levels do not appear to provide useful relevant clinical information.[63] Several levels of evidence strongly indicate diphenhydramine (similar to chlorpheniramine) can block the delayed rectifier potassium channel and, as a consequence, prolong the QT interval, leading to cardiac arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes.[64] No specific antidote for diphenhydramine toxicity is known, but the anticholinergic syndrome has been treated with physostigmine for severe delirium or tachycardia.[63] Benzodiazepines may be administered to decrease the likelihood of psychosis, agitation, and seizures in people who are prone to these symptoms.[65]

Interactions

editAlcohol may increase the drowsiness caused by diphenhydramine.[66][67]

Pharmacology

editPharmacodynamics

edit| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | ≥3,800 | Human | [69][70] |

| NET | 960–2,400 | Human | [69][70] |

| DAT | 1,100–2,200 | Human | [69][70] |

| 5-HT2C | 780 | Human | [70] |

| α1B | 1,300 | Human | [70] |

| α2A | 2,900 | Human | [70] |

| α2B | 1,600 | Human | [70] |

| α2C | 2,100 | Human | [70] |

| D2 | 20,000 | Rat | [71] |

| H1 | 9.6–16 | Human | [72][70] |

| H2 | >100,000 | Canine | [73] |

| H3 | >10,000 | Human | [70][74][75] |

| H4 | >10,000 | Human | [75] |

| M1 | 80–100 | Human | [76][70] |

| M2 | 120–490 | Human | [76][70] |

| M3 | 84–229 | Human | [76][70] |

| M4 | 53–112 | Human | [76][70] |

| M5 | 30–260 | Human | [76][70] |

| VGSC | 48,000–86,000 | Rat | [77] |

| hERG | 27,100 (IC50) | Human | [78] |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Diphenhydramine, available in various salt forms,[79] such as citrate,[80][81] hydrochloride,[82] and salicylate,[83] exhibits distinct molecular weights and pharmacokinetic properties. Specifically, diphenhydramine hydrochloride and diphenhydramine citrate possess molecular weights of 291.8 g/mol[84] and 447.5 g/mol,[85] respectively. These variations in molecular weight influence the dissolution rates and absorption characteristics of each salt form. Consequently, a dose of 25 mg diphenhydramine hydrochloride is therapeutically equivalent to 38 mg of diphenhydramine citrate. As such, dosage adjustments are necessary to account for these differences when switching between salt forms.[86]

Diphenhydramine, while traditionally known as an antagonist, acts primarily as an inverse agonist of the histamine H1 receptor.[87] It is a member of the ethanolamine class of antihistaminergic agents.[45] By reversing the effects of histamine on the capillaries, it can reduce the intensity of allergic symptoms. It also crosses the blood–brain barrier and inversely agonizes the H1 receptors centrally.[87] Its effects on central H1 receptors cause drowsiness.

Diphenhydramine is a potent antimuscarinic (a competitive antagonist of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors) and, as such, at high doses can cause anticholinergic syndrome.[88] The utility of diphenhydramine as an antiparkinson agent is the result of its blocking properties on the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain.

Diphenhydramine also acts as an intracellular sodium channel blocker, which is responsible for its actions as a local anesthetic.[77] Diphenhydramine has also been shown to inhibit the reuptake of serotonin.[23] It has been shown to be a potentiator of analgesia induced by morphine, but not by endogenous opioids, in rats.[89] The drug has also been found to act as an inhibitor of histamine N-methyltransferase (HNMT).[90][91]

| Biological target | Mode of action | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| H1 receptor | Inverse agonist | Allergy reduction; Sedation |

| mACh receptors | Antagonist | Anticholinergic; Antiparkinson |

| Sodium channels | Blocker | Local anesthetic |

Pharmacokinetics

editOral bioavailability of diphenhydramine is in the range of 40% to 60%, and peak plasma concentration occurs about 2 to 3 hours after administration.[5]

The primary route of metabolism is two successive demethylations of the tertiary amine. The resulting primary amine is further oxidized to the carboxylic acid.[5] Diphenhydramine is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP2D6, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19.[9]

The elimination half-life of diphenhydramine has not been fully elucidated, but appears to range between 2.4 and 9.3 hours in healthy adults.[6] A 1985 review of antihistamine pharmacokinetics found that the elimination half-life of diphenhydramine ranged between 3.4 and 9.3 hours across five studies, with a median elimination half-life of 4.3 hours.[5] A subsequent 1990 study found that the elimination half-life of diphenhydramine was 5.4 hours in children, 9.2 hours in young adults, and 13.5 hours in the elderly.[7] A 1998 study found a half-life of 4.1 ± 0.3 hours in young men, 7.4 ± 3.0 hours in elderly men, 4.4 ± 0.3 hours in young women, and 4.9 ± 0.6 hours in elderly women.[92] In a 2018 study in children and adolescents, the half-life of diphenhydramine was 8 to 9 hours.[93]

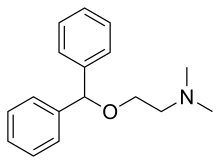

Chemistry

editDiphenhydramine is a diphenylmethane derivative. Analogues of diphenhydramine include orphenadrine, an anticholinergic, nefopam, an analgesic, and tofenacin, an antidepressant.

Detection in body fluids

editDiphenhydramine can be quantified in blood, plasma, or serum.[94] Gas chromatography with mass spectrometry (GC-MS) can be used with electron ionization on full scan mode as a screening test. GC-MS or GC-NDP can be used for quantification.[94] Rapid urine drug screens using immunoassays based on the principle of competitive binding may show false-positive methadone results for people having ingested diphenhydramine.[95] Quantification can be used to monitor therapy, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in people who are hospitalized, provide evidence in an impaired driving arrest, or assist in a death investigation.[94]

Marketing

editDiphenhydramine is sold under the brand name Benadryl by McNeil Consumer Healthcare in the U.S., UK, Canada, and South Africa.[96] Trade names in other countries include Dimedrol, Daedalon, Nytol, and Vivinox. It is also available as a generic medication.

Procter & Gamble markets an over-the-counter formulation of diphenhydramine as a sleep aid under the brand ZzzQuil.[97]

Prestige Brands markets an over-the-counter formulation of diphenhydramine as a sleep aid in the U.S. under the name Sominex.[98]

Cultural impact

editDiphenhydramine is deemed to have limited abuse potential in the United States owing to its potentially serious side-effect profile and limited euphoric effects, and is not a controlled substance. Since 2002, the U.S. FDA has required special labeling warning against use of multiple products that contain diphenhydramine.[99] In some jurisdictions, diphenhydramine is often present in postmortem specimens collected during investigation of sudden infant deaths; the drug may play a role in these events.[100][101]

Diphenhydramine is among prohibited and controlled substances in the Republic of Zambia,[102] and travelers are advised not to bring the drug into the country. Several Americans have been detained by the Zambian Drug Enforcement Commission for possession of Benadryl and other over-the-counter medications containing diphenhydramine.[103]

Recreational use

editAlthough diphenhydramine is widely used and generally considered to be safe for occasional usage, multiple cases of abuse and addiction have been documented.[19] Because the drug is cheap and sold over the counter in most countries, adolescents without access to more sought-after illicit drugs are particularly at risk.[104] People with mental health problems—especially those with schizophrenia—are also prone to abuse the drug, which is self-administered in large doses to treat extrapyramidal symptoms caused by the use of antipsychotics.[105]

Recreational users report calming effects, mild euphoria, and hallucinations as the desired effects of the drug.[105][106] Research has shown that antimuscarinic agents, including diphenhydramine, "may have antidepressant and mood-elevating properties".[107] A study conducted on adult males with a history of sedative abuse found that subjects who were administered a high dose (400 mg) of diphenhydramine reported a desire to take the drug again, despite also reporting negative effects, such as difficulty concentrating, confusion, tremors, and blurred vision.[108]

In 2020, an Internet challenge emerged on social media platform TikTok involving deliberately overdosing on diphenhydramine; dubbed the Benadryl challenge, the challenge encourages participants to consume dangerous amounts of Benadryl for the purpose of filming the resultant psychoactive effects, and has been implicated in several hospitalisations[109] and at least two deaths.[110][111][112]

References

edit- ^ Hubbard JR, Martin PR (2001). Substance Abuse in the Mentally and Physically Disabled. CRC Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8247-4497-7.

- ^ a b c Saran JS, Barbano RL, Schult R, Wiegand TJ, Selioutski O (October 2017). "Chronic diphenhydramine abuse and withdrawal: A diagnostic challenge". Neurology. Clinical Practice. 7 (5): 439–441. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000304. PMC 5874453. PMID 29620065.

- ^ "Benylin Chesty Coughs (Original) - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine- diphenhydramine hydrochloride injection, solution". DailyMed. 11 November 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Paton DM, Webster DR (1985). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of H1-receptor antagonists (the antihistamines)". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 10 (6): 477–97. doi:10.2165/00003088-198510060-00002. PMID 2866055. S2CID 33541001.

- ^ a b AHFS Drug Information. Published by authority of the Board of Directors of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. 1990. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ a b Simons KJ, Watson WT, Martin TJ, Chen XY, Simons FE (July 1990). "Diphenhydramine: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in elderly adults, young adults, and children". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 30 (7): 665–71. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1990.tb01871.x. PMID 2391399. S2CID 25452263.

- ^ a b Garnett WR (February 1986). "Diphenhydramine". American Pharmacy. NS26 (2): 35–40. doi:10.1016/s0095-9561(16)38634-0. PMID 3962845.

- ^ a b Krystal AD (August 2009). "A compendium of placebo-controlled trials of the risks/benefits of pharmacological treatments for insomnia: the empirical basis for U.S. clinical practice". Sleep Med Rev. 13 (4): 265–74. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2008.08.001. PMID 19153052.

- ^ "Showing Diphenhydramine (DB01075)". DrugBank. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Dörwald FZ (2013). Lead Optimization for Medicinal Chemists: Pharmacokinetic Properties of Functional Groups and Organic Compounds. John Wiley & Sons. p. 225. ISBN 978-3-527-64565-7. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016.

- ^ "Benadryl". Ohio History Central. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Diphenhydramine Hydrochloride". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 6 September 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Ayd FJ (2000). Lexicon of Psychiatry, Neurology, and the Neurosciences. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-7817-2468-5. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b Schroeck JL, Ford J, Conway EL, Kurtzhalts KE, Gee ME, Vollmer KA, et al. (November 2016). "Review of Safety and Efficacy of Sleep Medicines in Older Adults". Clinical Therapeutics. 38 (11): 2340–2372. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.09.010. PMID 27751669.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ a b Thomas A, Nallur DG, Jones N, Deslandes PN (January 2009). "Diphenhydramine abuse and detoxification: a brief review and case report". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 23 (1): 101–5. doi:10.1177/0269881107083809. PMID 18308811. S2CID 45490366.

- ^ Hevesi D (29 September 2007). "George Rieveschl, 91, Allergy Reliever, Dies". The New York Times.

- ^ Sneader W (23 June 2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- ^ Ritchie J (24 September 2007). "UC prof, Benadryl inventor dies". Business Courier of Cincinnati. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ^ a b c Domino EF (1999). "History of modern psychopharmacology: a personal view with an emphasis on antidepressants". Psychosomatic Medicine. 61 (5): 591–8. doi:10.1097/00006842-199909000-00002. PMID 10511010.

- ^ Awdishn RA, Whitmill M, Coba V, Killu K (October 2008). "Serotonin reuptake inhibition by diphenhydramine and concomitant linezolid use can result in serotonin syndrome". Chest. 134 (4 Meeting abstracts): 4C. doi:10.1378/chest.134.4_MeetingAbstracts.c4002. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Barondes SH (2003). Better Than Prozac. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-19-515130-5.

- ^ "FDA Orders Sominex 2 Withdrawn From Market". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Vol. 125, no. 336. 2 December 1975. p. 2. Retrieved 16 April 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Hydrochloride Monograph". Drugs.com. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.

- ^ Brown HE, Stoklosa J, Freudenreich O (December 2012). "How to stabilize an acutely psychotic patient" (PDF). Current Psychiatary. 11 (12): 10–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2013.

- ^ Smith DW, Peterson MR, DeBerard SC (August 1999). "Local anesthesia. Topical application, local infiltration, and field block". Postgraduate Medicine. 106 (2): 57–60, 64–6. doi:10.3810/pgm.1999.08.650. PMID 10456039.

- ^ a b American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. "Diphenhydramine Hydrochloride". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ a b Banerji A, Long AA, Camargo CA (2007). "Diphenhydramine versus nonsedating antihistamines for acute allergic reactions: a literature review". Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 28 (4): 418–26. doi:10.2500/aap.2007.28.3015. PMID 17883909. S2CID 7596980.

- ^ Young WF (2011). "Chapter 11: Shock". In Humphries RL, Stone CK (eds.). CURRENT Diagnosis and Treatment Emergency Medicine. LANGE CURRENT Series (Seventh ed.). McGraw–Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-170107-5.

- ^ Sheikh A, ten Broek VM, Brown SG, Simons FE (January 2007). "H1-antihistamines for the treatment of anaphylaxis with and without shock". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (1): CD006160. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006160.pub2. PMC 6517288. PMID 17253584.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Topical". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Aminoff MJ (2012). "Chapter 28. Pharmacologic Management of Parkinsonism & Other Movement Disorders". In Katzung B, Masters S, Trevor A (eds.). Basic & Clinical Pharmacology (12th ed.). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 483–500. ISBN 978-0-07-176401-8.

- ^ Monson K, Schoenstadt A (8 September 2013). "Benadryl Addiction". eMedTV. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Dinndorf PA, McCabe MA, Friedrich S (August 1998). "Risk of abuse of diphenhydramine in children and adolescents with chronic illnesses". The Journal of Pediatrics. 133 (2): 293–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70240-9. PMID 9709726.

- ^ Crier F (2 August 2017). "Is it wrong to drug your children so they sleep on a flight?". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Morris R (3 April 2013). "Should parents drug babies on long flights?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Swanson WS (25 November 2009). "If It Were My Child: No Benadryl for the Plane". Seattle Children's. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL (February 2017). "Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline". J Clin Sleep Med. 13 (2): 307–349. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6470. PMC 5263087. PMID 27998379.

- ^ De Crescenzo F, D'Alò GL, Ostinelli EG, Ciabattini M, Di Franco V, Watanabe N, et al. (July 2022). "Comparative effects of pharmacological interventions for the acute and long-term management of insomnia disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 400 (10347): 170–184. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00878-9. hdl:11380/1288245. PMID 35843245. S2CID 250536370.

- ^ Flake ZA, Scalley RD, Bailey AG (March 2004). "Practical selection of antiemetics". American Family Physician. 69 (5): 1169–74. PMID 15023018. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Medical Economics (2000). Physicians' Desk Reference for Nonprescription Drugs and Dietary Supplements, 2000 (21st ed.). Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company. ISBN 978-1-56363-341-6.

- ^ a b c Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollmann B (2011). "Chapter 32. Histamine, Bradykinin, and Their Antagonists". In Brunton L (ed.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12e ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 242–245. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ "High risk medications as specified by NCQA's HEDIS Measure: Use of High Risk Medications in the Elderly" (PDF). National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2010.

- ^ "2012 AGS Beers List" (PDF). The American Geriatrics Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Spencer JP, Gonzalez LS, Barnhart DJ (July 2001). "Medications in the breast-feeding mother". American Family Physician. 64 (1): 119–26. PMID 11456429.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine". Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) Internet. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). October 2020. PMID 30000938.

- ^ a b de Leon J, Nikoloff DM (February 2008). "Paradoxical excitation on diphenhydramine may be associated with being a CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizer: three case reports". CNS Spectrums. 13 (2): 133–5. doi:10.1017/s109285290001628x. PMID 18227744. S2CID 10856872.

- ^ American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, vol. 45, no. 3, American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, pp. 595–605, doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.12.002, PMID 23434175, archived from the original on 1 September 2013, retrieved 17 May 2024, which cites

- Smith TJ, Ritter JK, Poklis JL, Fletcher D, Coyne PJ, Dodson P, et al. (May 2012). "ABH gel is not absorbed from the skin of normal volunteers". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 43 (5): 961–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.017. PMID 22560361.

- Weschules DJ (December 2005). "Tolerability of the compound ABHR in hospice patients". Journal of Palliative Medicine. 8 (6): 1135–43. doi:10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1135. PMID 16351526.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2012. PMID 31643789. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Does Benadryl help with or cause anxiety?". Drugs.com. 27 July 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Diphenhydramine Side Effects". Drugs.com. 3 October 2024. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ Aronson JK (2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Cardiovascular Drugs. Elsevier. p. 623. ISBN 978-0-08-093289-7. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ Heine A (November 1996). "Diphenhydramine: a forgotten allergen?". Contact Dermatitis. 35 (5): 311–312. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02402.x. PMID 9007386. S2CID 32839996.

- ^ Coskey RJ (February 1983). "Contact dermatitis caused by diphenhydramine hydrochloride". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 8 (2): 204–206. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(83)70024-1. PMID 6219138.

- ^ "Restless Legs Syndrome Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ Salahudeen MS, Duffull SB, Nishtala PS (March 2015). "Anticholinergic burden quantified by anticholinergic risk scales and adverse outcomes in older people: a systematic review". BMC Geriatrics. 15 (31): 31. doi:10.1186/s12877-015-0029-9. PMC 4377853. PMID 25879993.

- ^ Sicari V, Zabbo CP (2021). "Diphenhydramine". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30252266. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Huynh DA, Abbas M, Dabaja A (2021). Diphenhydramine Toxicity. PMID 32491510.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine overdose". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013.

- ^ a b Manning B (2012). "Chapter 18. Antihistamines". In Olson K (ed.). Poisoning & Drug Overdose (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-166833-0. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Khalifa M, Drolet B, Daleau P, Lefez C, Gilbert M, Plante S, et al. (February 1999). "Block of potassium currents in guinea pig ventricular myocytes and lengthening of cardiac repolarization in man by the histamine H1 receptor antagonist diphenhydramine". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 288 (2): 858–65. PMID 9918600.

- ^ Cole JB, Stellpflug SJ, Gross EA, Smith SW (December 2011). "Wide complex tachycardia in a pediatric diphenhydramine overdose treated with sodium bicarbonate". Pediatric Emergency Care. 27 (12): 1175–7. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823b0e47. PMID 22158278. S2CID 5602304.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine and Alcohol / Food Interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013.

- ^ Zimatkin SM, Anichtchik OV (1999). "Alcohol-histamine interactions". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 34 (2): 141–7. doi:10.1093/alcalc/34.2.141. PMID 10344773.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (December 1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". European Journal of Pharmacology. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Krystal AD, Richelson E, Roth T (August 2013). "Review of the histamine system and the clinical effects of H1 antagonists: basis for a new model for understanding the effects of insomnia medications". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 17 (4): 263–72. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2012.08.001. PMID 23357028.

- ^ Tsuchihashi H, Sasaki T, Kojima S, Nagatomo T (1992). "Binding of [3H]haloperidol to dopamine D2 receptors in the rat striatum". J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 44 (11): 911–4. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1992.tb03235.x. PMID 1361536. S2CID 19420332.

- ^ Ghoneim OM, Legere JA, Golbraikh A, Tropsha A, Booth RG (October 2006). "Novel ligands for the human histamine H1 receptor: synthesis, pharmacology, and comparative molecular field analysis studies of 2-dimethylamino-5-(6)-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalenes". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 14 (19): 6640–58. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.05.077. PMID 16782354.

- ^ Gantz I, Schäffer M, DelValle J, Logsdon C, Campbell V, Uhler M, et al. (1991). "Molecular cloning of a gene encoding the histamine H2 receptor". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 (2): 429–33. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88..429G. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.2.429. PMC 50824. PMID 1703298.

- ^ Lovenberg TW, Roland BL, Wilson SJ, Jiang X, Pyati J, Huvar A, et al. (June 1999). "Cloning and functional expression of the human histamine H3 receptor". Molecular Pharmacology. 55 (6): 1101–7. doi:10.1124/mol.55.6.1101. PMID 10347254. S2CID 25542667.

- ^ a b Liu C, Ma X, Jiang X, Wilson SJ, Hofstra CL, Blevitt J, et al. (March 2001). "Cloning and pharmacological characterization of a fourth histamine receptor (H(4)) expressed in bone marrow". Molecular Pharmacology. 59 (3): 420–6. doi:10.1124/mol.59.3.420. PMID 11179434. S2CID 123619.

- ^ a b c d e Bolden C, Cusack B, Richelson E (February 1992). "Antagonism by antimuscarinic and neuroleptic compounds at the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 260 (2): 576–80. PMID 1346637.

- ^ a b Kim YS, Shin YK, Lee C, Song J (October 2000). "Block of sodium currents in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons by diphenhydramine". Brain Research. 881 (2): 190–8. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02860-2. PMID 11036158. S2CID 18560451.

- ^ Suessbrich H, Waldegger S, Lang F, Busch AE (April 1996). "Blockade of HERG channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes by the histamine receptor antagonists terfenadine and astemizole". FEBS Letters. 385 (1–2): 77–80. Bibcode:1996FEBSL.385...77S. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00355-9. PMID 8641472. S2CID 40355762.

- ^ Wang C, Paul S, Wang K, Hu S, Sun CC (2017). "Relationships among Crystal Structures, Mechanical Properties, and Tableting Performance Probed Using Four Salts of Diphenhydramine". Crystal Growth & Design. 17 (11): 6030–6040. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.7b01153.

- ^ Rao DD, Venkat Rao P, Sait SS, Mukkanti K, Chakole D (2009). "Simultaneous Determination of Ibuprofen and Diphenhydramine Citrate in Tablets by Validated LC". Chromatographia. 69 (9–10): 1133–1136. doi:10.1365/s10337-009-0977-3. S2CID 97766056.

- ^ Rao DD, Sait SS, Mukkanti K (April 2011). "Development and validation of an UPLC method for rapid determination of ibuprofen and diphenhydramine citrate in the presence of impurities in combined dosage form". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 49 (4): 281–286. doi:10.1093/chrsci/49.4.281. PMID 21439118.

- ^ Chan CY, Wallander KA (February 1991). "Diphenhydramine toxicity in three children with varicella-zoster infection". DICP. 25 (2): 130–132. doi:10.1177/106002809102500204. PMID 2058184. S2CID 45456788.

- ^ Kamijo Y, Soma K, Sato C, Kurihara K (November 2008). "Fatal diphenhydramine poisoning with increased vascular permeability including late pulmonary congestion refractory to percutaneous cardiovascular support". Clinical Toxicology. 46 (9): 864–868. doi:10.1080/15563650802116151. PMID 18608279. S2CID 43642257.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine Hydrochloride". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine citrate". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Pope C (28 August 2023). "Diphenhydramine Hydrochloride vs Citrate: What's the difference?". drugs.com.

- ^ a b Khilnani G, Khilnani AK (September 2011). "Inverse agonism and its therapeutic significance". Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 43 (5): 492–501. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.84947. PMC 3195115. PMID 22021988.

- ^ Lopez AM (10 May 2010). "Antihistamine Toxicity". Medscape Reference. WebMD LLC. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010.

- ^ Carr KD, Hiller JM, Simon EJ (February 1985). "Diphenhydramine potentiates narcotic but not endogenous opioid analgesia". Neuropeptides. 5 (4–6): 411–4. doi:10.1016/0143-4179(85)90041-1. PMID 2860599. S2CID 45054719.

- ^ Horton JR, Sawada K, Nishibori M, Cheng X (October 2005). "Structural basis for inhibition of histamine N-methyltransferase by diverse drugs". Journal of Molecular Biology. 353 (2): 334–344. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.040. PMC 4021489. PMID 16168438.

- ^ Taylor KM, Snyder SH (May 1972). "Histamine methyltransferase: inhibition and potentiation by antihistamines". Molecular Pharmacology. 8 (3): 300–10. PMID 4402747.

- ^ Scavone JM, Greenblatt DJ, Harmatz JS, Engelhardt N, Shader RI (July 1998). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of diphenhydramine 25 mg in young and elderly volunteers". J Clin Pharmacol. 38 (7): 603–9. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04466.x. PMID 9702844. S2CID 24989721.

- ^ Gelotte CK, Zimmerman BA, Thompson GA (May 2018). "Single-Dose Pharmacokinetic Study of Diphenhydramine HCl in Children and Adolescents". Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 7 (4): 400–407. doi:10.1002/cpdd.391. PMC 5947143. PMID 28967696.

- ^ a b c Pragst F (2007). "Chapter 13: High performance liquid chromatography in forensic toxicological analysis". In Smith RK, Bogusz MJ (eds.). Forensic Science (Handbook of Analytical Separations). Vol. 6 (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. p. 471. ISBN 978-0-444-52214-6.

- ^ Rogers SC, Pruitt CW, Crouch DJ, Caravati EM (September 2010). "Rapid urine drug screens: diphenhydramine and methadone cross-reactivity". Pediatric Emergency Care. 26 (9): 665–6. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181f05443. PMID 20838187. S2CID 31581678.

- ^ "Childrens Benadryl Allergy (solution) Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc., McNeil Consumer Healthcare Division". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Is P&G Preparing to Expand ZzzQuil?". Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Diphenhydramine". Mother To Baby | Fact Sheets [Internet]. National Library of Medicine. January 2023. PMID 35951938. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ Food and Drug Administration, HHS (December 2002). "Labeling of diphenhydramine-containing drug products for over-the-counter human use. Final rule". Federal Register. 67 (235): 72555–9. PMID 12474879. Archived from the original on 5 November 2008.

- ^ Marinetti L, Lehman L, Casto B, Harshbarger K, Kubiczek P, Davis J (October 2005). "Over-the-counter cold medications-postmortem findings in infants and the relationship to cause of death". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 29 (7): 738–43. doi:10.1093/jat/29.7.738. PMID 16419411.

- ^ Baselt RC (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man. Biomedical Publications. pp. 489–492. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ^ "List of prohibited and controlled drugs according to chapter 96 of the laws of Zambia". The Drug Enforcement Commission ZAMBIA. Archived from the original (DOC) on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ "Zambia". Country Information > Zambia. Bureau of Consular Affairs, U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Forest E (27 July 2008). "Atypical Drugs of Abuse". Articles & Interviews. Student Doctor Network. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013.

- ^ a b Halpert AG, Olmstead MC, Beninger RJ (January 2002). "Mechanisms and abuse liability of the anti-histamine dimenhydrinate" (PDF). Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 26 (1): 61–7. doi:10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00038-0. PMID 11835984. S2CID 46619422. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Gracious B, Abe N, Sundberg J (December 2010). "The importance of taking a history of over-the-counter medication use: a brief review and case illustration of "PRN" antihistamine dependence in a hospitalized adolescent". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 20 (6): 521–4. doi:10.1089/cap.2010.0031. PMC 3025184. PMID 21186972.

- ^ Dilsaver SC (February 1988). "Antimuscarinic agents as substances of abuse: a review". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 8 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1097/00004714-198802000-00003. PMID 3280616. S2CID 31355546.

- ^ Mumford GK, Silverman K, Griffiths RR (1996). "Reinforcing, subjective, and performance effects of lorazepam and diphenhydramine in humans". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 4 (4): 421–430. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.4.4.421.

- ^ "TikTok Videos Encourage Viewers to Overdose on Benadryl". TikTok Videos Encourage Viewers to Overdose on Benadryl. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "Dangerous 'Benadryl Challenge' on Tik Tok may be to blame for the death of Oklahoma teen". KFOR.com Oklahoma City. 28 August 2020. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "Teen's Death Prompts Warning on 'Benadryl Challenge'". medpagetoday.com. 25 September 2020. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "What is the Benadryl challenge? New TikTok challenge that's left 13-year-old dead". The Independent. 23 April 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

Further reading

edit- Björnsdóttir I, Einarson TR, Gudmundsson LS, Einarsdóttir RA (December 2007). "Efficacy of diphenhydramine against cough in humans: a review". Pharmacy World & Science. 29 (6): 577–83. doi:10.1007/s11096-007-9122-2. PMID 17486423. S2CID 8168920.

- Cox D, Ahmed Z, McBride AJ (March 2001). "Diphenhydramine dependence". Addiction. 96 (3): 516–7. PMID 11310441.

- Lieberman JA (2003). "History of the use of antidepressants in primary care" (PDF). Primary Care Companion J. Clinical Psychiatry. 5 (supplement 7): 6–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

External links

editMedia related to Diphenhydramine at Wikimedia Commons