Boogie Nights is a 1997 American period drama film written, directed, and co-produced by Paul Thomas Anderson.[3] It is set in Los Angeles's San Fernando Valley and focuses on a young nightclub dishwasher who becomes a popular star of pornographic films, chronicling his rise in the Golden Age of Porn of the 1970s through his fall during the excesses of the 1980s. The film is an expansion of Anderson's mockumentary short film The Dirk Diggler Story (1988),[4][5][6][7] and stars Mark Wahlberg, Julianne Moore, Burt Reynolds, Don Cheadle, John C. Reilly, William H. Macy, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and Heather Graham.

| Boogie Nights | |

|---|---|

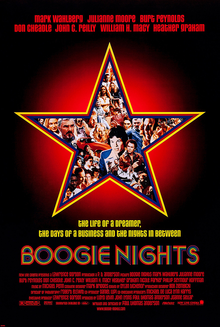

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Paul Thomas Anderson |

| Written by | Paul Thomas Anderson |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Elswit |

| Edited by | Dylan Tichenor |

| Music by | Michael Penn |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 155 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million[2] |

| Box office | $43.1 million[2] |

Boogie Nights premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 11, 1997, and was theatrically released by New Line Cinema on October 10, 1997, garnering critical acclaim. It was nominated for three Academy Awards, including Best Original Screenplay for Anderson, Best Supporting Actress for Moore, and Best Supporting Actor for Reynolds. The film's soundtrack also received acclaim. It has since been considered one of Anderson's best works and one of the best films of all time.[8][9]

Plot

editIn 1977, high-school dropout Eddie Adams is living with his father and emotionally and physically abusive mother in Torrance, California. He works at a Reseda nightclub owned by Maurice Rodriguez, where he meets porn filmmaker Jack Horner. Interested in bringing Eddie into porn, Jack auditions him by watching him have sex with Rollergirl, a porn starlet who always wears skates.

After a fight with his mother, Eddie moves in with Jack at his San Fernando Valley home. He gives himself the screen name "Dirk Diggler" and becomes a star because of his good looks, youthful charisma, and abnormally large penis. His success allows him to buy a new house, an extensive wardrobe, and a "competition orange" 1977 Chevrolet Corvette. With his friend and co-star Reed Rothchild, Dirk pitches a series of successful action-themed porn films. He works and socializes with others from the porn industry, and they live carefree lifestyles in the late 1970s disco era. While attending a New Year's Eve party at Horner's house on December 31, 1979, assistant director Little Bill discovers his adulterous wife having sex with another man. Bill, tired of being repeatedly cheated on, shoots the pair dead and commits suicide.

Dirk and Reed begin using cocaine on a regular basis. Due to his drug use, Dirk finds it increasingly difficult to achieve an erection, falls into violent mood swings, and becomes irritated with Johnny Doe, a rival leading man Jack has recently recruited, and whom Dirk worries will replace him. In 1983, after arguing with Jack, Dirk is fired and takes off with Reed to start a music career along with Scotty, a boom operator who is in love with Dirk. Jack rejects business overtures from Floyd Gondolli, a local theater magnate who insists on cutting costs by shooting on videotape rather than film stock, because Jack believes that video will diminish the quality of his films.

After his friend and financier, Colonel James, is incarcerated for possession of child pornography, Jack cooperates with Gondolli but becomes disillusioned with the work he is expected to churn out. One of these projects involves Jack and Rollergirl riding in a limousine, searching for random men for her to have sex with while being taped by a crew. One man recognizes Rollergirl as a former high-school classmate, and after a failed attempt at intercourse, he insults her and Jack. Both Jack and Rollergirl attack the man, leaving him bloodied on the sidewalk.

Leading lady Amber Waves lands in a custody battle with her ex-husband. The court determines that she is an unfit mother due to her involvement in the porn industry, criminal record, and cocaine addiction. Buck Swope marries fellow porn star Jessie St. Vincent, who becomes pregnant. Because of his past as a pornographer, Buck is disqualified from a bank loan and cannot open his own stereo equipment store. That night, he finds himself in the middle of a holdup at a donut shop in which the clerk, the robber, and an armed customer are killed. Buck is the sole survivor and escapes with the money.

Having spent most of their money on drugs, Dirk and Reed are unable to pay a recording studio for demo tapes they believe will enable them to become music stars. Desperate for money, Dirk resorts to prostitution but is assaulted and robbed by three men. Dirk, Reed, and their friend Todd Parker attempt to scam local drug dealer Rahad Jackson at his estate by selling him a half-kilo of baking soda disguised as cocaine. Dirk and Reed intend to leave quickly before Rahad's bodyguard inspects it, but a drugged-up and armed Todd attempts to steal more money, as well as some more drugs, from Rahad. In the ensuing gunfight, Todd kills Rahad's bodyguard and is killed by Rahad, while Dirk and Reed narrowly escape. Dirk returns to Jack's home and they reconcile.

In 1984, Amber shoots the television commercial for the opening of Buck's store, Rollergirl takes a GED class, Maurice opens a nightclub with his brothers, Reed performs magic acts at a strip club, and Jessie gives birth to her and Buck's son. Dirk, Jack, and Amber prepare to start filming again.

Cast

edit- Mark Wahlberg as Eddie Adams / Dirk Diggler

- Julianne Moore as Maggie / Amber Waves

- Burt Reynolds as Jack Horner

- Don Cheadle as Buck Swope

- John C. Reilly as Reed Rothchild

- William H. Macy as Little Bill

- Heather Graham as Brandy / Rollergirl

- Nicole Ari Parker as Becky Barnett

- Philip Seymour Hoffman as Scotty J.

- Luis Guzmán as Maurice Rodriguez / T. T. Rodriguez

- Philip Baker Hall as Floyd Gondolli

- Thomas Jane as Todd Parker

- Robert Ridgely as The Colonel James

- Robert Downey Sr. as Burt

- Nina Hartley as Little Bill's Wife

- Melora Walters as Jessie St. Vincent

- Alfred Molina as Rahad Jackson

- Ricky Jay as Kurt Longjohn

- Joanna Gleason as Dirk's mother

- Laurel Holloman as Sheryl Lynn

- Michael Jace as Jerome

- Michael Penn as Nick

Production

editDevelopment

editBoogie Nights is based on a mockumentary short film that Paul Thomas Anderson wrote and directed while he was still in high school called The Dirk Diggler Story.[4] The short itself was based on the 1981 documentary Exhausted: John C. Holmes, The Real Story, a documentary about the life of legendary porn actor John Holmes, on whom Dirk Diggler is based.[10]

Anderson originally wanted the role of Eddie to be played by Leonardo DiCaprio, after seeing him in The Basketball Diaries. DiCaprio enjoyed the screenplay, but had to turn it down because he had signed on to star in James Cameron's Titanic. He recommended his Basketball Diaries co-star Mark Wahlberg for the role.[10] DiCaprio would later say that he wished he had done both.[11] Joaquin Phoenix was also offered the role of Eddie, but he declined it due to concerns about playing a porn star. Phoenix later collaborated with Anderson on the films The Master and Inherent Vice.[12] Bill Murray, Harvey Keitel, Warren Beatty, Albert Brooks and Sydney Pollack declined or were passed up on the role of Jack Horner, which went to Burt Reynolds.[13][14] After starring in Hard Eight, Samuel L. Jackson declined the role of Buck Swope, which went to Don Cheadle.[10] Anderson initially did not consider Heather Graham for Rollergirl, because he had never seen her do nudity in a film. However, Graham's agent called Anderson asking if she could read for the part, which she won.[10] Gwyneth Paltrow, Drew Barrymore and Tatum O'Neal were also up for the role.[13][15]

After having a very difficult time getting his previous film, Hard Eight, released, Anderson laid down a hard law when making Boogie Nights. He initially wanted the film to be over three hours long and be rated NC-17. The film's producers, particularly Michael De Luca, said that the film had to be either under three hours or rated R. Anderson fought with them, saying that the film would not have a mainstream appeal no matter what. They did not change their minds, and Anderson chose the R rating as a challenge. Despite this, the film was still 25 minutes shorter than promised.[10]

Reynolds did not get along with Anderson while filming. After seeing a rough cut of the film, Reynolds allegedly fired his agent for recommending it.[16][better source needed] Despite this, Reynolds won a Golden Globe Award and was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance. Later, Anderson wanted Reynolds to star in his next film, Magnolia, but Reynolds declined.[17] In 2012, Reynolds denied rumours that he disliked the film, calling it "extraordinary" and saying that his opinion of it has nothing to do with his relationship with Anderson.[18] According to Wahlberg, Reynolds wanted his character Jack Horner to have an Irish accent.[19][20]

Release

editThe film premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and was shown at the New York Film Festival, before opening on two screens in the United States on October 10, 1997. It grossed $50,168 during its opening weekend. Three weeks later, it expanded to 907 theaters and grossed $4.7 million, ranking number four for the week. It eventually earned $26.4 million in the United States and $16.7 million in foreign markets for a worldwide box office total of $43.1 million.[21]

Reception

editOn review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, Boogie Nights holds an approval rating of 94% based on 77 reviews, with an average score of 8.10/10. The site's critical consensus states, "Grounded in strong characters, bold themes, and subtle storytelling, Boogie Nights is a groundbreaking film both for director P.T. Anderson and star Mark Wahlberg."[22] On Metacritic, the film holds a weighted average score of 86 out of 100, based on 28 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[23] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "C" on an A+ to F scale.[24]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times wrote, "Everything about Boogie Nights is interestingly unexpected," although "the film's extravagant 2-hour 32-minute length amounts to a slight tactical mistake ... [it] has no trouble holding interest ... but the length promises larger ideas than the film finally delivers." She praised Burt Reynolds for "his best and most suavely funny performance in many years," and added, "The movie's special gift happens to be Mark Wahlberg, who gives a terrifically appealing performance."[25]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times observed:

Few films have been more matter-of-fact, even disenchanted, about sexuality. Adult films are a business here, not a dalliance or a pastime, and one of the charms of Boogie Nights is the way it shows the everyday backstage humdrum life of porno filmmaking ... The sweep and variety of the characters have brought the movie comparisons to Robert Altman's Nashville and The Player. There is also some of the same appeal as Pulp Fiction in scenes that balance precariously between comedy and violence ... Through all the characters and all the action, Anderson's screenplay centers on the human qualities of the players ... Boogie Nights has the quality of many great films, in that it always seems alive.[26]

Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle stated, "Boogie Nights is the first great film about the 1970s to come out since the '70s ... It gets all the details right, nailing down the styles and the music. More impressive, it captures the decade's distinct, decadent glamour ... [It] also succeeds at something very difficult: re-creating the ethos and mentality of an era ... Paul Thomas Anderson ... has pulled off a wonderful, sprawling, sophisticated film ... With Boogie Nights, we know we're not just watching episodes from disparate lives but a panorama of recent social history, rendered in bold, exuberant colors."[27]

Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times called it "a startling film, but not for the obvious reasons. Yes, its decision to focus on the pornography business in the San Fernando Valley in the 1970s and 1980s is nerviness itself, but more impressive is the film's sureness of touch, its ability to be empathetic, nonjudgmental and gently satirical, to understand what is going on beneath the surface of this raunchy Nashville-esque universe and to deftly relate it to our own ... Perhaps the most exciting thing about Boogie Nights is the ease with which writer-director Anderson ... spins out this complex web. A true storyteller, able to easily mix and match moods in a playful and audacious manner, he is a filmmaker definitely worth watching, both now and in the future."[28] In Time Out New York, Andrew Johnston concluded, "The porn milieu may scare some folks off, but Boogie Nights offers laughs, tenderness, terror and redemption--everything you could ask for in a movie. It's an impressive and satisfying film, one the Academy really ought to have the balls to recognize."[29]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone said, "[T]his chunk of movie dynamite is detonated by Mark Wahlberg ... who grabs a breakout role and runs with it ... Even when Boogie Nights flies off course as it tracks its bizarrely idealistic characters into the '80s ... you can sense the passionate commitment at the core of this hilarious and harrowing spectacle. For this, credit Paul Thomas Anderson ... who ... scores a personal triumph by finding glints of rude life in the ashes that remained after Watergate. For all the unbridled sex, what is significant, timely and, finally, hopeful about Boogie Nights is the way Anderson proves that a movie can be mercilessly honest and mercifully humane at the same time."[30]

Gene Siskel of Chicago Tribune called it "beautifully made" and praised the performances, calling Reynolds "absolutely centered and in control of his emotions" and saying Wahlberg "couldn't be better". However, he moderated his praise by saying, "The early rave reviews accorded this film suggest a significance that I, however, did not encounter. Show-biz stories are all pretty much the same: ambition, stardom, drugs, disillusionment. Add the home video revolution to this mix and curiosity about the size of the boy wonder's equipment; throw in a few topical references like the soft drink Fresca, and you have the bare bones of the story." He gave the film three and a half stars out of a possible four.[31]

Despite the accolades Wahlberg received for his performance in Boogie Nights, he would later express regret for having made the film. "I've made some poor choices in the past", he said.[32]

Accolades

editMusic

edit| Boogie Nights: Music from the Original Motion Picture | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album | |

| Released | October 7, 1997 |

| Genre | Disco, pop, soul |

| Label | Capitol |

| Boogie Nights 2: More Music from the Original Motion Picture | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album | |

| Released | January 13, 1998 |

| Genre | Disco, pop, soul |

| Label | Capitol |

Two Boogie Nights soundtracks were released, the first at the time of the film's initial release and the second the following year. AllMusic rated the first soundtrack four and a half stars out of five[59] and the second soundtrack four.[60]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Intro (Feel the Heat)" | Paul Thomas Anderson, John C. Reilly | Reilly, Mark Wahlberg | 1:11 |

| 2. | "Best of My Love" | Al McKay, Maurice White | The Emotions | 3:39 |

| 3. | "Jungle Fever" | Bill Ador | Chakachas | 4:20 |

| 4. | "Brand New Key" | Melanie Safka | Melanie Safka | 2:23 |

| 5. | "Spill the Wine" | Eric Burdon and War | Eric Burdon and War | 4:02 |

| 6. | "Got to Give It Up, Pt. 1" | Marvin Gaye | Marvin Gaye | 4:07 |

| 7. | "Machine Gun" | Milan Williams | Commodores | 2:38 |

| 8. | "Magnet and Steel" | Walter Egan | Walter Egan | 3:23 |

| 9. | "Ain't No Stoppin' Us Now" | Jerry Cohen, Gene McFadden, John Whitehead | McFadden & Whitehead | 3:40 |

| 10. | "Sister Christian" | Kelly Keagy | Night Ranger | 5:00 |

| 11. | "Livin' Thing" | Jeff Lynne | Electric Light Orchestra | 3:30 |

| 12. | "God Only Knows" | Tony Asher, Brian Wilson | The Beach Boys | 2:48 |

| 13. | "The Big Top (Theme from "Boogie Nights")" | Michael Penn | Penn, Patrick Warren | 9:58 |

| Total length: | 50:39 | |||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Mama Told Me (Not to Come)" | Randy Newman | Three Dog Night | 3:16 |

| 2. | "Fooled Around and Fell in Love" | Elvin Bishop | Elvin Bishop | 4:34 |

| 3. | "You Sexy Thing" | Errol Brown, Tony Wilson | Hot Chocolate | 4:02 |

| 4. | "Boogie Shoes" | Harry Wayne Casey, Richard Finch | KC & the Sunshine Band | 2:09 |

| 5. | "Do Your Thing" | Charles Wright | Charles Wright & the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band | 3:29 |

| 6. | "Driver's Seat" | Paul Roberts | Sniff 'n' the Tears | 4:00 |

| 7. | "Feel Too Good" | Roy Wood | The Move | 9:30 |

| 8. | "Jessie's Girl" | Rick Springfield | Rick Springfield | 3:13 |

| 9. | "J.P. Walk" | Anton Scott | Sound Experience | 7:05 |

| 10. | "I Want to Be Free" | Marshall "Rock" Jones, Ralph "Pee Wee" Middlebrooks, James "Diamond" Williams | Ohio Players | 6:50 |

| 11. | "Joy" | Johann Sebastian Bach | Apollo 100 | 2:44 |

| Total length: | 53:23 | |||

- Personnel

- Paul Thomas Anderson – executive producer

- Karyn Rachtman – executive producer, music supervisor

- Liz Heller – executive producer[61]

- Bobby Lavelle – music supervisor

- Carol Dunn – music coordinator

Songs that appear in the film but not on either soundtrack albums

edit- "Sunny" by Boney M.

- "Susan (The Sage)" by Chico Hamilton Quintet

- "Fly, Robin, Fly" by Silver Convention

- "Afternoon Delight" by Starland Vocal Band

- "Lonely Boy" by Andrew Gold

- "Fat Man" by Jethro Tull

- "Flying Objects" by Roger Webb

- "Queen of Hearts" by Juice Newton

- "It's Just a Matter of Time" by Brook Benton

- "Compared to What" by Roberta Flack

- "99 Luftballons" by Nena

- "Voices Carry" by 'Til Tuesday

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Tied with Curtis Hanson for L.A. Confidential.

References

edit- ^ "Boggie Nights (18)". British Board of Film Classification. October 28, 1997. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ^ a b "Box Office Mojo: Boogie Nights". Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ O'Connor, Kyrie (March 26, 1998). "BOOGIE NIGHTS". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. Archived from the original on June 13, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ a b McKenna, Kristine (October 12, 1997). "Knows It When He Sees It". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ Waxman, Sharon R. (2005). Rebels on the backlot: six maverick directors and how they conquered the Hollywood studio system. HarperCollins. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-06-054017-3. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ Hirshberg, Lynn (December 19, 1999). "His Way". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ Mottram, James (2006). The Sundance Kids: how the mavericks took back Hollywood. NY: Faber & Faber, Inc. p. 129. ISBN 9780865479678.

cigarettes & coffee.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time". December 21, 2022. Archived from the original on June 18, 2023. Retrieved June 18, 2023.

- ^ "Boogie Nights at 25: Why it Might be Paul Thomas Anderson's Best Film". October 19, 2022. Archived from the original on June 18, 2023. Retrieved June 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Kirk, Jeremy (September 13, 2012). "37 Things We Learned From the 'Boogie Nights' Commentary". Film School Rejects. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ "Leading Man: Leonardo DiCaprio". November 2008. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (January 25, 2013). "Joaquin Phoenix set to star in Paul Thomas Anderson's Inherent Vice". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ a b Zakarin, Jordan (December 10, 2014). "5 Things We Just Learned About 'Boogie Nights'". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ "Livin' Thing". Archived from the original on December 22, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2022.

- ^ "Gwyneth Paltrow Turned Down These Blockbusters -- Does She Regret It?". January 15, 2015. Archived from the original on December 22, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2022.

- ^ Brew, Simon (March 1, 2010). "10 actors who turned against their own films". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin (December 3, 2015). ""He Was Young And Full Of Himself": Burt Reynolds On Why He "Hated" Paul Thomas Anderson During 'Boogie Nights'". Indiewire. Penske Business Media, LLC. Archived from the original on November 29, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ Mandatory (July 11, 2012), Deliverance Interviews (Ronny Cox, Jon Voight, Burt Reynolds & Ned Beatty), archived from the original on November 3, 2021, retrieved March 1, 2018

- ^ Thrash, Steven (March 17, 2024). "Mark Wahlberg Recalls Burt Reynolds' Blunt Behavior on Boogie Nights: 'Don't You Ever Laugh at Me Kid!'". MovieWeb. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ Bentz, Adam (March 15, 2024). ""Don't You Ever Laugh At Me, Kid": Mark Wahlberg & Burt Reynolds' First Boogie Nights Scene Went Very Awkwardly". Screen Rant. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "Box Office Mojo". IMDb. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ "Boogie Nights". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ "Boogie Nights". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Matt Singer (August 13, 2015). "25 Films With Completely Baffling CinemaScores". ScreenCrush. Archived from the original on September 7, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ "New York Times review". The New York Times. October 8, 1997. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ "RogerEbert.com review". RogerEbert.com. October 17, 1997. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (October 17, 1997). "San Francisco Chronicle review". SFGate.com. Archived from the original on December 28, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff. "Los Angeles Times review". CalendarLive.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ Johnston, Andrew (October 2–16, 1997). "Boogie Nights". Time Out New York: 77.

- ^ "Rolling Stone review" Archived June 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (October 17, 1997). "'Boggie' Grooves to an Off Beat". chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (October 24, 2017). "Mark Wahlberg Wants God to Forgive Him for 'Boogie Nights': 'I've Made Some Poor Choices'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on October 31, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ "The 70th Academy Awards (1998) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners". Casting Society of America. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "BSFC Winners: 1990s". Boston Society of Film Critics. July 27, 2018. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1998". BAFTA. 1998. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ "1988-2013 Award Winner Archives". Chicago Film Critics Association. January 2013. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "4th Annual Chlotrudis Awards". Chlotrudis Society for Independent Films. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ "The BFCA Critics' Choice Awards :: 1997". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Swart, Sharon (December 7, 1998). "Benigni, 'Dreamlife' top Euro film kudos". Variety. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ "1997 FFCC AWARD WINNERS". Florida Film Critics Circle. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Boogie Nights – Golden Globes". HFPA. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1997 Sierra Award Winners". December 13, 2021. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ^ "The 23rd Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1997 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. December 19, 2009. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1997 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Archived from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "2nd Annual Film Awards (1997)". Online Film & Television Association. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Film Hall of Fame Inductees: Productions". Online Film & Television Association. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ "1997 Online Film Critics Society Awards". Online Film Critics Society. January 3, 2012. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ "1998 Satellite Awards". Satellite Awards. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "The 4th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild Awards. Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (March 10, 1998). "Footlights". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 19, 2023. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ "Past SOC Winners". Society of Camera Operators. December 6, 2014. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ "1997 SEFA Awards". sefca.net. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Awards". Archived from the original on January 3, 2007.

- ^ "TFCA Past Award Winners". Toronto Film Critics Association. May 29, 2014. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Awards Winners". wga.org. Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ Allmusic review for the first soundtrack

- ^ Allmusic review for the second soundtrack

- ^ "Discogs – Liz Heller credit Boogie Nights #2 1997 Capitol Records (CDP 7243 4 93076 2 9) US". Discogs. 1998. Archived from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

External links

edit- Boogie Nights at IMDb

- Boogie Nights at Box Office Mojo

- Boogie Nights at Rotten Tomatoes

- Boogie Nights at Metacritic

- Boogie Nights script at the Internet Movie Script Database

- Paul Thomas Anderson radio interview

- "Livin' Thing: An Oral History of Boogie Nights", Grantland, December 2014