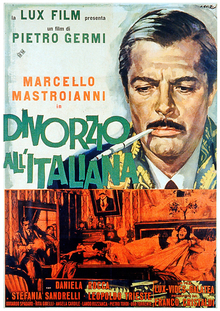

Divorce Italian Style (Italian: Divorzio all'italiana) is a 1961 Italian black comedy film directed by Pietro Germi. The screenplay is by Germi, Ennio De Concini, Alfredo Giannetti, and Agenore Incrocci, based on Giovanni Arpino's novel Un delitto d'onore (English title A Crime of Honor). It stars Marcello Mastroianni, Daniela Rocca, Stefania Sandrelli, Lando Buzzanca, and Leopoldo Trieste.

| Divorce Italian Style | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Pietro Germi |

| Screenplay by | Ennio De Concini Pietro Germi Alfredo Giannetti Agenore Incrocci (uncredited) |

| Based on | Un delitto d'onore 1960 novel by Giovanni Arpino |

| Produced by | Franco Cristaldi |

| Starring | Marcello Mastroianni Daniela Rocca Stefania Sandrelli Leopoldo Trieste Odoardo Spadaro |

| Cinematography | Carlo Di Palma Leonida Barboni |

| Edited by | Roberto Cinquini |

| Music by | Carlo Rustichelli |

| Distributed by | Embassy Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Box office | $2.3 million (US/Canada rentals)[1] |

It received the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, two Golden Globe Awards and numerous other International film prizes. In 2008, the film was included in the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage's 100 Italian films to be saved, a list of 100 films that "have changed the collective memory of the country between 1942 and 1978."[2]

Plot

editFerdinando Cefalù, a 37-year-old impoverished Sicilian nobleman, is married to Rosalia, a devoted wife he no longer loves. He is in love with his cousin Angela, a 16-year-old girl he sees only during the summer because her family sends her away to Catholic school in the city. Besides his wife, he shares his life with his elderly parents, his sister, and her fiancé, a funeral director. The family share their once stately palace with his uncles, who are slowly but surely eating away the remainders of their once rich estate.

Aware that divorce is illegal, Ferdinando fantasizes about doing away with his wife, such as by throwing her into a boiling cauldron, sending her into space in a rocket, or drowning her in quicksand. After a chance encounter with Angela during a family trip, he discovers that she shares his feelings.

Inspired by a local story of a woman who killed her husband in a rage of jealousy, he resolves to lead his wife into having an affair so that he can catch her in flagrante delicto, murder her, and receive a light sentence for committing an honour killing. He first needs to find a suitable lover for his wife, whom he finds in the local priest's godson, Carmelo Patanè, a painter who has had feelings for Rosalia for years. For a time he was presumed killed during World War II. Ferdinando also procures the State Prosecutor's friendship with a small favor. The final stage of his plan is to arrange for Carmelo's constant presence in his house, which he achieves by feigning interest in having his palace frescoes restored.

But Carmelo is timid with Rosalia, and she is initially committed to conjugal fidelity. Ferdinando tapes their private conversations and has to ward off the maid Sisina's infatuation with Carmelo. After Carmelo makes a pass at Sisina, she tells the priest, Carmelo's godfather, at confession, who informs her that Carmelo is married with three children. She relays that information to Ferdinando. Rosalia and Carmelo finally give in to their passion, but the tape of their conversation runs out just as they are arranging their next meeting. All Ferdinando knows is that it will take place the next evening.

Rosalia feigns a headache and remains home while the rest of the family goes to the cinema to see the local première of La Dolce Vita, a film so scandalous that no one wants to miss it. Ferdinando sneaks out of the theater and returns home, arriving just in time to see Rosalia leaving for the train station. He retrieves his gun to kill her, but arrives at the station just after their train departs. He revisits his plan and the Criminal Code. It defines a crime of passion as executed in the heat of the moment or in defense of one's honor, so he embraces the role of a cuckold.

All along, Angela has been writing Ferdinando to assure him of her undying love for him. Her last letter is misdelivered to her father, who dies of a heart attack upon reading it. At the funeral, Ferdinando is approached by Mrs. Patanè, who demands to know what he will do about their situation. After he responds noncommittally, she spits in his face in front of the entire town, which gives him what he needs: an open insult to the family's honor due to his wife's elopement.

The local Mafia boss offers to find the lovers within 24 hours, which he does. As Ferdinando goes to the lovers' hideout, he hears Mrs. Patanè kill Carmelo. He follows suit and kills Rosalia. At his trial he is defended by the State Prosecutor, who blames the whole thing on Ferdinando's father, saying that he failed to give his son enough love when raising him as a boy. Ferdinando is released from prison after three years and returns home to find Angela waiting for him.

Later, Ferdinando and Angela are happily sailing at sea. As they kiss, Angela seductively rubs her feet against those of the young workman piloting the boat.

Cast

edit- Marcello Mastroianni as Ferdinando Cefalù

- Daniela Rocca as Rosalia Cefalù

- Stefania Sandrelli as Angela

- Leopoldo Trieste as Carmelo Patanè

- Odoardo Spadaro as Don Gaetano Cefalù

- Margherita Girelli as Sisina

- Angela Cardile as Agnese

- Lando Buzzanca as Rosario Mulè

- Pietro Tordi as Attorney De Marzi

- Ugo Torrente as Don Calogero

- Antonio Acqua as Priest

- Bianca Castagnetta as Donna Matilde Cefalù

- Giovanni Fassiolo as Don Ciccio Matara

- Ignazio Roberto Daidone

- Francesco Nicastro

Release

editDivorce Italian Style was released in Rome in December 1961.[3]

Reception

editCritical Reception

editReview aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported an approval rating of 100% based on 17 reviews.[4] Upon release in the United States, Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called it "one of the funniest pictures the Italians have sent along" and praised Germi as "a genius with the sly twist."[5] James Powers of The Hollywood Reporter praised the "mocking, sardonic farce" as "bold, irreverent, and human to the bone," and he predicted it would be successful in America due its dual nature as both an arthouse film and a film that achieves general appeal.[6] Variety gave the film a positive review, calling the satire "a penetrating, almost brutal glimpse of Sicily and its antiquated way of life."[7][8]

Box Office

editWhen the film was released in the United States, it earned theatrical rentals of $803,666 in 1962 and a further $1,449,347 in 1963 for a total of $2,252,013 in the United States and Canada. It was still in release in 1964.[1]

Accolades

editAdaptations

editIn 2008 Giorgio Battistelli adapted Divorce Italian Style into an opera, Divorce à l'Italienne, which premiered by the Opéra national de Lorraine on September 30 of that year with tenor Wolfgang Ablinger Sperrhacke in Mastroianni's role. Battistelli chose to set every female role except Angela for low male voice; Bruno Praticò sang the role of Rosalia.[15]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "'Divorce-Italian Style,' $2,252,013". Variety. February 19, 1964. p. 5.

- ^ "Ecco i cento film italiani da salvare Corriere della Sera". www.corriere.it. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- ^ "Divorce--Italian Style". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 2, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Divorce Italian Style at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (September 18, 1962). "The Screen: 'Divorce--Italian Style'; 'Dandy Satiric Farce' at Paris Theater Marcello Mastroianni and Miss Rocca Star". The New York Times. p. 34. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

- ^ Powers, James (October 2, 1962). "Italo Production Has General Appeal". The Hollywood Reporter. p. 3. ProQuest 2339684721.

- ^ Hawk (September 26, 1962). "Divorce--Italian Style". Variety.

- ^ Variety Staff (1 January 1961). "Divorzio All'Italiana". Variety.

- ^ "The 35th Academy Awards (1963) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1964". BAFTA. 1964. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Divorzio all'Italiana". Festival de Cannes. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "15th DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Divorce Italian Style – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1962 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Opera News > the Met Opera Guild". Archived from the original on 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ Tied with Gina Rovere for Adua and Her Friends.

- ^ Tied with Robert Dhéry for La Belle Américaine.

External links

edit- Divorce Italian Style at IMDb

- Divorce Italian Style at AllMovie

- Divorce Italian Style at the TCM Movie Database

- Divorce Italian Style: The Facts (and Fancies) of Murder an essay by Stuart Klawans at the Criterion Collection

- Divorzio all'italiana is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive