Balipratipada (Bali-pratipadā), also called as Bali-Padyami, Padva, Virapratipada or Dyutapratipada, is the fourth day of Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights.[2][3] It is celebrated in honour of the notional return of the daitya-king Bali (Mahabali) to earth. Balipratipada falls in the Gregorian calendar months of October or November. It is the first (or 16th) day of the Hindu month of Kartika and is the first day of its bright lunar fortnight.[4][5][6] In many parts of India such as Gujarat and Rajasthan, it is the regional traditional New Year Day in Vikram Samvat and also called the Bestu Varas or Varsha Pratipada.[7][8] This is the half amongst the three and a half Muhūrtas in a year.

| Bali-pratipada | |

|---|---|

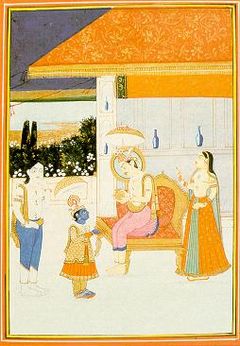

Vamana (blue faced dwarf) in the court of King Bali (Raja Bali, right seated) seeking alms | |

| Also called | Bali Padwa (Maharashtra), Bali Padyami (Andhra Pradesh ),(Karnataka), Barlaj (Himachal Pradesh), Raja Bali (Jammu), Gujarati New Year (Bestu Varas), Marwari New Year |

| Observed by | Hindus |

| Type | Hindu |

| Observances | Festival of lights as celebration of return of Mahabali to earth for a day |

| Date | Kartika 1 (amanta tradition) Kartika 16 (purnimanta tradition) |

| 2024 date | 2 November |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Diwali |

Hindu festival dates The Hindu calendar is lunisolar but most festival dates are specified using the lunar portion of the calendar. A lunar day is uniquely identified by three calendar elements: māsa (lunar month), pakṣa (lunar fortnight) and tithi (lunar day). Furthermore, when specifying the masa, one of two traditions are applicable, viz. amānta / pūrṇimānta. If a festival falls in the waning phase of the moon, these two traditions identify the same lunar day as falling in two different (but successive) masa. A lunar year is shorter than a solar year by about eleven days. As a result, most Hindu festivals occur on different days in successive years on the Gregorian calendar. | |

Balipratipada is an ancient festival. The earliest mention of Bali's story being acted out in dramas and poetry of ancient India is found in the c. 2nd-century BCE Mahābhāṣya of Patanjali on Panini's Astadhyayi 3.1.26.[3] The festival has links to the Vedic era sura-asura Samudra Manthana that revealed goddess Lakshmi and where Bali was the king of the asuras.[9] The festivities find mention in the Mahabharata,[3] the Ramayana,[10] and several major Puranas, such as the Brahma Purana, Kurma Purana, Matsya Purana and others.[3]

Balipratipada commemorates the annual return of Bali to earth and the victory of Vamana, the dwarf avatar of the god Vishnu. It marks the victory of Vishnu over Bali and all asuras, through his metamorphosis into Vamana-Trivikrama.[2] At the time of his defeat, Bali was already a Vishnu-devotee and a benevolent ruler over a peaceful, prosperous kingdom.[3] Vishnu's victory over Bali using "three steps" ended the war.[4][10] According to Hindu scriptures, Bali asked for and was granted the boon by Vishnu, whereby he returns to earth once a year when he will be remembered and worshipped, and reincarnate in a future birth as Indra.[3][11][12]

Balipratipada or Padva is traditionally celebrated with decorating the floor with colorful images of Bali – sometimes with his wife Vindyavati,[8] of nature's abundance, a shared feast, community events and sports, drama or poetry sessions. In some regions, rice and food offerings are made to recently dead ancestors (shraddha), or the horns of cows and bulls are decorated, people gamble, or icons of Vishnu avatars are created and garlanded in addition.[3][12][8][13]

Nomenclature

editBalipratipada (Sanskrit: बालि प्रतिपदा, Marathi: बळी-प्रतिपदा or Pāḍvā पाडवा, Kannada: ಬಲಿ ಪಾಡ್ಯಮಿ or Bali Pāḍyami) is a compound word consisting of "Bali" (a mythical daitya king, also known as Mahabali)[14] and "pratipada" (also called padva, means occasion, commence, first day of a lunar fortnight).[15] It is also called the Akashadipa (lights of the sky).[citation needed]

Texts

editThe Balipratipada and Bali-related scripture is ancient. The earliest mention of Bali's story is found in the c. 2nd-century BCE Mahābhāṣya of Patanjali on Panini's Astadhyayi 3.1.26. It states that "Balim bandhayati" refers to a person reciting the Bali legend or acting it out on a stage. This, states P.V. Kane – a Sanskrit literature scholar, attests that the "imprisonment of Bali" legend was well known by the 2nd-century BCE in forms of drama and poetry in ancient India.[3] According to Tracy Pintchman – an Indologist, the festival has links to the Samudra Manthana legend found in Vedic texts. These describe a cosmic struggle between suras and asuras, with Mahabali as the king of the asuras. It is this legendary churning of cosmic ocean that created Lakshmi – the goddess worshipped on Diwali. The remembrance and festivities associated with Lakshmi and Mahabali during Diwali are linked.[9]

The festivities related to Bali and Balipratipada find mention in the Vanaparva 28.2 of the Mahabharata,[3] the Ramayana,[10] and several major Puranas, such as the Brahma purana (chapter 73), Kurma purana (chapter 1), Matsya purana (chapters 245 and 246), and others.[3][16]

The Hindu text Dharmasindhu in its discussions of Diwali states that day after the Diwali night, Balipratipada is one of three most auspicious dates in the year.[3] It recommends an oil bath and a worship of Bali. His icon along with his wife's should be drawn on the floor with five colored powder and flowers.[3] Fruits and food should be offered to Bali, according to Bhavisyottra, and drama or other community spectacles should be organized.[3] The Hindu texts suggest that the devout should light lamps, wear new clothes, tie auspicious threads or wear garland, thank their tools of art, decorate and pray before the cows and bulls, organize delightful community sports (kaumudi-mahotsava) in temple or palace grounds such as pulling tug-of-war ropes.[3]

Legend

editBali was Prahlada's grandson. He came to power by defeating the gods (Devas), and taking over the three worlds. Bali, an Asura king was well known for his bravery, uprightness and dedication to god Vishnu. Bali had amassed vast territories and was invincible. He was benevolent and popular, but his close associates weren't like him. They were constantly attacking the suras (Devas) and plundering the gods who stood for righteousness and justice.[17][18]

According to Vaishnava scriptures, Indra and the defeated suras approached Vishnu for help in their battle with Bali.[19] Vishnu refused to join the gods in violence against Bali, because Bali was a good ruler and his own devotee. But, instead of promising to kill Bali, Vishnu promised to use a novel means to help the suras.[14][20]

Bali announced that he will perform Yajna (homa sacrifices) and grant anyone any gift they want during the Yajna. Vishnu took the avatar of a dwarf Brahmin called Vamana and approached Bali.[17][21] The king offered anything to the boy – gold, cows, elephants, villages, food, whatever he wished. The boy said that one must not seek more than one needs, and all he needs is the property right over a piece of land that measures "three paces". Bali agreed.[22][23] The Vamana grew to enormous proportions, metamorphosing into the Trivikrama form, and covered everything Bali ruled over in just two paces. For the third pace, Bali offered his own head to Vishnu who pushed him into the realm of Patala (nether world).[10][20]

Pleased with the dedication and integrity of Bali, Vishnu granted him a boon that he could return to earth for one day in a year to be with his people, be worshipped and be a future Indra.[3] It is this day that is celebrated as the Bali Padyami, the annual return of Bali from the netherworld to earth.[24]

Another version of the legend states that after Vamana pushed Bali below ground (patalaloka), at the request of Prahlada (described as a great devotee of Vishnu), the grandfather of Bali, Vishnu pardoned Bali and made him the king of the netherworld. Vishnu also granted the wish of Bali to return to earth for one day marked by festivities and his worship.[citation needed]

Festivities

editThe rituals observed on the Bali Padyami day have variations from state to state. In general, on this festival day, Hindus exchange gifts, as it is considered a way to please Bali and the gods. After the ceremonial Oil Bath, people wear new clothes. The main hall of the house or the space before the door or gate is decorated with a Rangoli or Kolam drawn with powder of rice in different colours, thereafter Bali and his wife Vindhyavali are worshipped. Some build Bali icons out of clay or cow dung. In the evening, as night falls, door sills of every house and temple are lighted with lamps arranged in rows. Community sports and feasts are a part of the celebrations.[3][21]

Some people gamble with a game called pachikalu (dice game), which is linked to a legend. It is believed that god Shiva and his consort Parvati played this game on this festival day when Parvati won. Following this, their son Kartikeya played with Parvati and defeated her. Thereafter, his brother, the elephant-headed god of wisdom Ganesha played with him and won the dice game. But now this gambling game is played only by family members, symbolically, with cards.[citation needed]

The farming community celebrates this festival, particularly in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, by performing Kedaragauri vratam (worship of goddess KedaraGauri – a form of Parvati), Gopuja (worship of cow), and Gouramma puja (worship of Gauri – another form of Parvati). Before worship of cows, on this day, the goushala (cowshed) is also ceremoniously cleaned. On this day, a triangular shaped image of Bali, made out of cow-dung is placed over a wooden plank designed with colourful Kolam decorations and bedecked with marigold flowers and worshipped.[6]

Himachal Pradesh

editBali Pratipada is also known as Barlaj in Himachal Pradesh. Barlaj is corruption of word Bali Raj. Vishnu and his devotee Bali is worshipped on this day.[25] Bali, the grandson of Prahlada is believed to visit earth on this day. Folk songs of Vamana are also sung this day.[26] Farmers do not use plough on this day and artisans worship their tools and implements on this day in honour of Vishvakarma. Ekaloo, a rice flour based dish is prepared on this day.[27]

Jammu division

editThis day is simply known as Raja Bali in Jammu region. Women prepare murtis of Raja Bali using wheat dough and later on Bali Puja is performed.[28] These murtis are then immersed in water after Puja.

Related festivals

editOnam is a major festival of Kerala based on the same scriptures, but observed in August–September. In the contemporary era, it commemorates Mahabali. Celebrations include a vegetarian feast, gift giving, parades featuring Bali and Vishnu avataras, floor decorations and community sports.[29][22] According to A.M. Kurup, the history of Onam festival as evidenced by literature and inscriptions found in Kerala suggest "Onam was a temple-based community festival celebrated over a period".[30] The festivities of Onam are found in Maturaikkāñci – a Sangam era Tamil poem, which mentions the festival being celebrated in Madurai temples with games and duels in temple premises, oblations being sent to the temples, people wore new clothes and feasted.[30] The 9th-century Pathikas and Pallads by Saint Sage Periyalawar, according to Kurup, describes Onam celebrations and offerings to Vishnu, mentions feasts and community events.[30] Several inscriptions from 11th and 12th-century in Hindu temples such as the Thrikkakara Temple (Kochi, dedicated to Vamana) and the Sreevallabha Temple (Tiruvalla, dedicated to Vishnu) attest to offerings dedicated to Vamana on Onam.[30] In contemporary Kerala, the festival is observed by both Hindus and non-Hindus,[31] with the exception of Muslims among whom isolated celebration is observed.[32]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ BSE India, India Financial Market Holidays (2020)

- ^ a b Manu Belur Bhagavan; Eleanor Zelliot; Anne Feldhaus (2008). 'Speaking Truth to Power': Religion, Caste, and the Subaltern Question in India. Oxford University Press. pp. 94–103. ISBN 978-0-19-569305-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p PV Kane (1958). History of Dharmasastra, Volume 5 Part 1. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. pp. 201–206.

- ^ a b Ramakrishna, H. A.; H. L. Nage Gowda (1998). Essentials of Karnataka folklore: a compendium. Karnataka Janapada Parishat. p. 258. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Devi, Konduri Sarojini (1990). Religion in Vijayanagara Empire. Sterling Publishers. p. 277. ISBN 9788120711679. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Hebbar, B. N. (2005). The Śrī-Kṛṣṇa Temple at Uḍupi: the historical and spiritual center of the ... Bharatiya Granth Niketan. p. 237. ISBN 978-81-89211-04-2. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Bestu Varas: For Gujratis celebrations continue the day after Diwali too, The Times of India (October 25, 2011)

- ^ a b c K. Gnanambal (1969). Festivals of India. Anthropological Survey of India. pp. 5–17.

- ^ a b Tracy Pintchman (2005). Guests at God's Wedding: Celebrating Kartik among the Women of Benares. State University of New York Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-7914-6595-0.

- ^ a b c d Narayan, R.K (1977). The Ramayana: a shortened modern prose version of the Indian epic. Penguin Classics. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-0-14-018700-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Yves Bonnefoy (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- ^ a b Joanna Gottfried Williams (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL. p. 70. ISBN 90-04-06498-2.

- ^ J. P. Vaswani (2017). Dasavatara. Jaico Publishing House. pp. 73–77. ISBN 978-93-86867-18-6.

- ^ a b Roshen Dalal (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6.

- ^ P. Prabhu (1885). Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. Government central Press. pp. 238–239.

- ^ Deborah A. Soifer (1991). The Myths of Narasimha and Vamana: Two Avatars in Cosmological Perspective. State University of New York Press. pp. Appendix II (193–274). ISBN 978-0-7914-0799-8.

- ^ a b Raghavendra, T.N. (2002). Vishnu Sahasranama. SRG Publishers. pp. 233–235. ISBN 978-81-902827-2-7. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Roshen Dalal (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. p. 900. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- ^ a b Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ a b Arvind Sharma (1996). Hinduism for our times. Oxford University Press. pp. 54–56. ISBN 9780195637496.

- ^ a b J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. pp. 659–670. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- ^ Nanditha Kirshna (2009). Book of Vishnu. Penguin Books. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-81-8475-865-8.

- ^ Singhal, Jwala Prasad (1963). The Sphinx speaks. Sadgyan Sadan. p. 92. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Registrar, India Office of the; General, India Office of the Registrar (1962). Census of India, 1961: Himachal Pradesh. Manager of Publications.

- ^ Singh, Kumar Suresh (1993). The Mahābhārata in the Tribal and Folk Traditions of India. Indian Institute of Advanced Study and Anthropological Survey of India, New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-85952-17-8.

- ^ Registrar, India Office of the; General, India Office of the Registrar (1962). Census of India, 1961: Himachal Pradesh. Manager of Publications.

- ^ Hamārā sāhitya (in Hindi). Lalitakalā, Saṃskṛti, va Sāhitya Akādamī, Jammū-Kaśmīra. 2008.

- ^ Fuller, Christopher John (2001). The everyday state and society in modern India. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 140–142. ISBN 978-1-85065-471-1. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d A.M. Kurup (1977). "The Sociology of Onam". Indian Anthropologist. 7 (2): 95–110. JSTOR 41919319.

- ^ Osella, Filippo; Osella, Caroline (2001). Fuller, Christopher John; Bénéï, Véronique (eds.). The Everyday State and Society in Modern India. C. Hurst. pp. 137–139. ISBN 978-1850654711.

- ^ Osella, Caroline; Osella, Filippo (2008). "Food, Memory, Community: Kerala as both 'Indian Ocean' Zone and as Agricultural Homeland" (PDF). Journal of South Asian Studies. 31 (1): 170–198. doi:10.1080/00856400701877232. S2CID 145738369., Quote: "Onam is of course not celebrated by Muslims; for it commemorates the victory of the Hindu demon king Mahabali who, in Hindu lore, founded Kerala. Contemporary Islamic reformist ulema even advise Muslims to refuse invitations from Hindu neighbours who may wish to call them to eat on Thiruvonam. From the outset, then, this Muslim family’s plan to make an Onam feast had the air of a daring and naughty secret."

Further reading

edit- Deborah A. Soifer (1991). The Myths of Narasimha and Vamana: Two Avatars in Cosmological Perspective. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0799-8.