Dobson's Encyclopædia was the first encyclopedia issued in the newly independent United States of America, published by Thomas Dobson from 1789 to 1798.[1] Encyclopædia was the full title of the work, with Dobson's name at the bottom of the title page (see illustration).

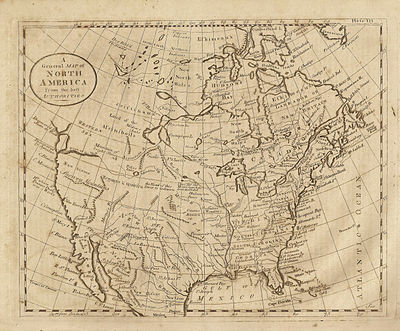

The encyclopedia was a reprint of the contemporary third edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (published 1788–1797), although Dobson's Encyclopædia was a somewhat longer work in which a few articles were edited for a patriotic American audience. The term Britannica was dropped from the title, the dedication to King George III was replaced with a dedication to the readers, and sundry facts about American history, geography and peoples were added. Reproduction of printed pages was not then possible; the entire work was re-set in type, allowing changes to be made throughout. However, the work is largely a reprint of Britannica. The plates were re-engraved from the originals as accurately as possible, but some were changed. For example, the map of North America used in Britannica's third edition was the very out-of-date one used in the first and second editions; Dobson's used a larger and much more detailed and updated map, and a slightly improved map of South America.

History

editThe 18-volume third edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica was published between 1788 (Volume 1) and 1797 (Volume 18) in Scotland, and was well received. It was by far the best edition of the Britannica to date (see: History of the Encyclopædia Britannica for more details). A two-volume supplement was added in 1801.

In this era, enterprising American printers were matching their British counterparts in quality and quantity, and severely undercutting them in price. A successful master printer, Dobson objected to a British bias he perceived in the Britannica, and resolved to re-edit the Britannica accordingly. He completed his Encyclopædia in April 1798, a year after the original. It had 16,650 pages, with 595 engraved copperplates, slightly more than the Britannica. In support of Dobson's patriotic initiative, President George Washington subscribed to two sets, one of which now is kept with most of the rest of George Washington's personal library in the Boston Athenæum.

Its retail price was five Pennsylvania dollars per volume, about 15% less than the price of Britannica in America, subject to import tax on British books.[2] Purchasers included George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton.[3] The original printing of 2,000 copies had sold out by 1818, at which time he still had a quantity of the 3-volume supplement remaining. To sell it, he had new title pages for the 3 volumes printed up dated 1818, and called them the Encyclopedia.[4] By the time of Dobson's death in 1823 the Encyclopædia was outdated, and was eventually superseded by the first edition of Encyclopedia Americana (1829–1833).

Subscription sales

editDobson did not approve of door-to-door sales, which had been used by his contemporary Parson Weems to sell William Guthrie's New System of Modern Geography and Oliver Goldsmith's History of the earth and Animated Nature. The door-to-door approach also seemed impractical, given the Encyclopædia's price and the long printing time of nine years. Instead, Dobson conducted an all-out advertising blitz, unlike any before seen in North America, to secure subscriptions; his advertisements appeared in newspapers, on magazine wrappers, in spare book leaves, and in pamphlets distributed to all the major book-sellers of his day. Dobson also appealed strongly to the patriotic pride of the newly independent Americans; he used only American materials and craftspeople and his announcement of the first "American" encyclopedia was timed to match George Washington's selection as the first President under the new Constitution. His first advertisements appeared on 31 March 1789 in three newspapers: the Pennsylvania Mercury, the Pennsylvania Packet, and the Federal Gazette.

Printing

editLike the Britannica, Dobson's Encyclopædia was published in weekly numbers, which could be then bound into volumes or half-volume parts. The price of each number was "one quarter of a dollar". The first weekly number was published on 2 January 1790, followed the next week by the second number. Dobson continued his regular printings until a fire destroyed his business and stock on an early Sunday morning, 8 September 1793; the heat of the fire was sufficient to melt much of his metal print parts. Dobson was again printing his Encyclopædia within a month.

Editorial difficulties

editDobson encountered some editorial difficulties, most notably on the essay concerning Quakers in Volume 15, which roused some indignation in Philadelphia, the home of many Quakers. Dobson had merely reprinted an offensive article from the Britannica which had been written by George Gleig (later Bishop of Brechin), without checking it for accuracy. A devout Anglican, Gleig showed bias against George Fox, the founder of the Quakers. Dobson met this challenge by meeting with the Quakers and printing a rebuttal essay in defense of George Fox's character. The Quakers' approaches to race relations and other social issues were often noted as enlightened and praised throughout the Encyclopædia.[citation needed]

Comparison with the Britannica's third edition

editMost of Dobson's Encyclopædia is a copy of the third edition of the Britannica. The chief exceptions can be found in the articles dealing with American geography, most notably Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, and American history, such as the surrender of the British in the American Revolution. A very detailed account of that war, in both Britannica and Dobson's, makes up roughly the second half of the article "America" in Vol 1. In Britannica, it goes from page 574 to 618, in Dobson's from 575 to 626, making Dobson's account seven pages longer. Volume 1 of Dobson's is re-paginated back to 619 after the article, to once again line up with Britannica.

In addition to Dobson himself, Jedidiah Morse, the father of American geography, made significant contributions; for example, he defended the status of women among the Native American peoples, which had been called "slavish" by the Britannica's editors, most likely James Tytler:

We may confidently and safely assert that the condition of women among many of the American tribes is as respectable and important as it was among the Germans, in the day of Tacitus, or as it is among many other nations with whom we are acquainted, in a similar stage of improvement.

— Jedidiah Morse, in Dobson's Encyclopædia

Morse also disputed the view of the Britannica that the skins and skulls of Indians were "thicker than the skins and skulls of many other nations of mankind".

It is likely that there were other contributors to Dobson's Encyclopædia, but their names are unknown.

The Supplement

editDobson began thinking about his supplement even before the Encyclopedia was finished. He began work on it before Britannica advertised their intention of producing a supplement, and when the British supplement started to be printed, Dobson had a good amount of additional material to include with it. His supplement, dated 1803, was 3 volumes long, compared with the two-volume supplement published by the Britannica in 1801. The Supplement was more independent and more accurate than the main encyclopedia had been, but sales were relatively poor. One notable article is "Pneumatics", which correctly defends Count Rumford's conclusion that water is a relatively poor conductor of heat, which had been criticized by an important Britannica contributor, Dr. Thomas Thomson of Edinburgh.

The differences between the texts of Encyclopædia Britannica and Dobson's Encyclopaedia are mostly found in the supplement. The 1803 two-volume second edition of Britannica's supplement had 1,622 pages; Dobson's three-volume supplement had 2,004, and 53 plates against the Britannica's 50.

Almost all the added pages in Dobson's supplement involved American interests, such as expanded descriptions of the states, of New York City and Boston, with hundreds of added cities and locations, descriptions of Indian tribes and their locations and customs, great expansion of American political leaders, an expanded article on the first president, and an entirely new four-page article for Benjamin Franklin.[5] There was an article on Franklin in the 3rd edition of Britannica, and he was mentioned many times in various other articles, but no article in its supplement. The Britannica had a four-page article on Washington; Dobson's supplement repeats it and adds four more pages. Dobson's supplement had a 30-page article on "The United States of America" not in the Britannica's supplement.

The Supplement was printed by Budd and Bartram of Philadelphia.

Competition

editDobson's Encyclopædia encountered significant competition from his rival printer, Thomas Bradford of Philadelphia, who proposed in 1805 to reprint Abraham Rees' New Cyclopaedia with American amendments. The 44-volume British original first began to appear in London in January 1803, but was not completed until 1820; the 47-volume American reprint was not completed until 1822. Not only did the project drive Bradford bankrupt, it also drove his successor bankrupt, the firm of Murray, Draper, Fairman and Company. Dobson was vulnerable to competition due to two factors: his encyclopedia was beginning to be outdated, and it had relatively few biographies of Americans. Dobson and his son Judah eventually went out of business in 1822; Dobson died on 9 March 1823.

A New York City competitor was Low's Encyclopaedia which was printed between 1805 and 1811. It was a more compact work, containing only seven volumes of 650 pages each (Dobson's 18 volumes were 800 pages). It was aimed at a market for more general circulation, being one-fourth the price and more portable, whereas Dobson's was aimed at the wealthy class. Low's was not a reprint of an earlier British work, but was mostly of American authorship, and all the plates and maps were engraved by Low from original sources. Low's Encyclopedia appears to have gone out of business after a single edition, as John Low died in 1809 and his widow Esther Prentiss Low, who took over and completed the work, died in 1816.

A very compact four-volume encyclopedia, the Minor Encyclopedia of 1803, was an American revision of Kendal's Pocket Encyclopedia, and was so small it did not compete with the former two works.

A more successful encyclopedia following Dobson's was the 13-volume Encyclopedia Americana, published 1829–1833 by Francis Lieber. The Encyclopedia Americana was based on Brockhaus' Conversations-Lexikon, with significant added material.

See also

editReferences

editNotes

- ^ Arner, Robert D. (1991). Dobson's Encyclopaedia: The Publisher, Text, and Publication of America's First Britannica, 1789-1803. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ^ Sher, Richard B. The Enlightenment & the book: Scottish authors & their publishers

- ^ Wells, James M. (1968). The Circle of Knowledge: Encyclopaedias Past and Present. Chicago: The Newberry Library. Library of Congress catalog number 68-21708.

- ^ Arner, Robert D. (1991). Dobson's Encyclopaedia: The Publisher, Text, and Publication of America's First Britannica, 1789–1803. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Page 180.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 1803 supplement and Dobson's 1803 supplement.

Bibliography

- Arner, Robert D. (1991). Dobson's Encyclopaedia: The Publisher, Text, and Publication of America's First Britannica, 1789-1803. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Well-researched with exhaustive citations to primary sources, this is the authoritative source on all matters pertaining to Dobson's Encyclopædia.

External links

edit- Media related to Dobson's Encyclopædia at Wikimedia Commons