Hatha Yoga: The Report of a Personal Experience is a 1943 book by Theos Casimir Bernard describing what he learnt of hatha yoga, ostensibly in India. It is one of the first books in English to describe and illustrate a substantial number of yoga poses (asanas); it describes the yoga purifications (shatkarmas), yoga breathing (pranayama), yogic seals (mudras), and meditative union (samadhi) at a comparable level of detail.

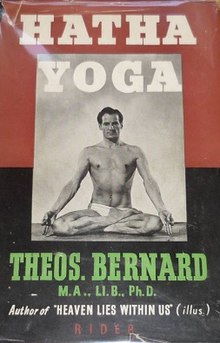

Cover of first edition, showing the author in Ardha Padmasana | |

| Author | Theos Casimir Bernard |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Hatha yoga |

| Publisher | Columbia University Press |

Publication date | 1943 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | |

| OCLC | 458483074 |

The book has been called an important forerunner of the major guides to modern yoga by B. K. S. Iyengar and others. Scholars including Norman Sjoman and Mark Singleton have considered the book a rare example of a complete yoga system actually being followed, and being evaluated at each stage by a practitioner-scholar. However, Bernard's biographer Douglas Veenhof states that Bernard invented the Indian guru whom he had refused to name, as he had instead apparently been taught by his father.

The 37 high-quality monochrome studio photographs of Bernard executing the poses are among the first published images of an American doing yoga.

Context

editAfter visiting India and Tibet, Bernard completed his Ph.D. in a single year at Columbia University under the supervision of Herbert Schneider.[1][2] In 1943 he published it as a book.[3][4] It was one of the earliest references in the West, possibly the first in English, on the asanas and other practices of hatha yoga (preceded by Sport és Jóga in Spanish in 1941).[5]

Summary

editDespite its title, Hatha Yoga: The Report of a Personal Experience was less personal and more technical than Bernard's fictionalised 1939 account of hatha yoga, Heaven Lies Within Us.[6] An introduction explains the principles of hatha yoga.[7]

Overview

editThe main part of the book recounts Bernard's own experience, starting with a chapter on asanas and the reason he was "prescribed" them by his teacher.[a] There follow chapters on purifications (shatkarmas), yoga breathing (pranayama), yogic seals (mudras), and meditative union (samadhi). Asanas are seen to be just one component of hatha yoga. There is a short biography of the author and an academic bibliography with primary sources—the Yoga Sutras, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Siva Samhita, and the Gheranda Samhita—and the secondary sources available to him, including Kuvalayananda's 1931 Asanas and Sir John Woodroffe's 1918 Shakti and Shakta.[9]

He describes his experiences with asanas "calculated to bring a rich supply of blood to the brain and ... the spinal cord", namely sarvangasana (shoulderstand), halasana (plough), pascimottanasana (forward bend), and mayurasana (peacock);[10] and "reconditioning asanas" to "stretch, bend, and twist the spinal cord", namely salabhasana (locust), bhujangasana (cobra), and dhanurasana (bow).[11] These mastered, he took on the meditation asanas, the most important being the cross-legged siddhasana and padmasana, though he also learnt other meditation seats, muktasana, guptasana, bhadrasana, gorakshasana, and svastikasana, and the kneeling meditation poses vajrasana and simhasana. He then worked in detail on sirsasana (headstand) and its variations.[9]

Bernard learnt all six purifications, dhauti (cleaning the digestive tract), basti (colonic irrigation), neti (nasal wash), trataka (fixed gazing), nauli (abdominal massage by the abdominal muscles), and kapalabhati (skull-polishing breath).[12]

In pranayama, he learnt surya bhedana (the so-called sun-piercing breath), sitting in siddhasana and employing the abdominal lock uddiyana bandha to help move the air. He then learnt ujjayi breathing (meaning "victorious"), sitkari (hissing sound) and sitali (cooling breath), followed by the cleansing bhastrika and the soothing bhramari (buzzing like a bee[b]). The goal of pranayama, he states, is kevala, the suspension of breath; he became able to hold his breath for four minutes at a time, but found doing this repeatedly "almost impossible". He was taught to accompany this with khechari mudra, the folding back of the tongue, enabling his kevala to extend to five minutes.[13]

The mudras that Bernard practised were maha bandha (all three body locks at once), khechari mudra as just described, uddiyana, the supplementary technique of asvini mudra, jalandhara bandha (throat lock), pasini mudra, vajroli mudra (other locks), and "yogasana" (by which was meant yogamudrasana, the legs in lotus position, the body folded forward).[15]

The account of samadhi, which Bernard did not claim to have attained, is necessarily largely theoretical, quoting the medieval texts at some length. However, he goes on a three-month retreat to study with "a well-trained Yogi at his hermitage",[16] based on "the theory of an inner light".[17] After two months, he sees the lights, which are of different colours. The retreat ends with "a ceremony that occasionally is employed to establish fully the inner experience of absorbing the mind in these lights."[18] His teacher makes clear that "no amount of ceremony can awaken Kundalini."[18] Bernard concludes that during his studies of yoga he "found that it holds no magic, performs no miracles, and reveals nothing supernatural";[19] as for "the Knowledge of the True",[20] that, he states, "must remain a mystery".[21]

Illustrations

editThe book is illustrated with 37 high-quality monochrome photographs, all of Bernard himself executing asanas, mudras and bandhas (body locks) as described in the text. 19 of these are full-page illustrations; the remainder are half-page. The last five plates all show stages in Uddiyana Bandha. All have a studio background of diffuse clouds and a plain floor with lighting from the front and above, as seen in the illustration of Sirsasana discussed below.[22] These were among the first photos of an American executing yoga poses ever published.[23]

Bernard was an accomplished photographer himself, shooting "an astounding 326 rolls of film (11,736 exposures) as well as 20,000 feet of motion picture film"[24] during his three months in Tibet in a "near obsessive documentation"[24] of what he saw. In the view of Namiko Kunimoto, Bernard's photographs taken in the East served to authenticate the travel narrative and to construct Tibet "as a site of personal transformation."[24] Back in the United States, Bernard's photographs of himself, whether in Tibetan dress or performing yoga poses such as Baddhapadmasana in the studio (a photo that also appears as plate XX in the book[c]), appeared frequently in Family Circle magazine from 1938, "reveal[ing] his willingness to commodify spirituality and assumptions of exoticism".[24]

Approach

editIn his Preface, Bernard explains his approach to the studies he undertook:

When I went to India, I did not present myself as an academic research student, trying to probe into the intimacies of ancient cultural patterns; instead, I became a disciple[d] and in this way one of the Yogis in body and spirit, without reservation, for I wanted to 'taste' their teachings. This required that I take part in many religious ceremonies, for everything in India is steeped in the formalities of rites and rituals.[25]

Bernard's approach to the book is to describe each task he was given simply and directly, stating its purpose, and then his own experience of working with it, together with any advice he was given about it. For example, on Sirsasana he writes:

One of the most important postures that I was required to perfect is called sirsasana (head stand, see Plate XXVIII) and deserves special comment. This posture is not listed in the [medieval] texts as an asana, but it is described among the mudras under the name viparita karani (inverted body).[e] ... As in the attainment of all asanas, I was advised to proceed with due caution. My teacher assured me that there is no danger for anyone in a normal state of health who is mindful of every change that takes place and allows ample time for the system to accommodate itself to the inverted position. At first it seemed hopeless, especially when I found that the standard for perfection is three hours.[28]

Bernard explains how he went about the task, indicating both his dedication and the time required to reach the prescribed standard:

To accomplish this goal without any setbacks, my teacher advised me to start with ten seconds for the first week and then to add thirty seconds each week until I brought the time up to fifteen minutes. This required several months. At this point I was advised to repeat the practice twice a day, which gave me a total of thirty minutes. After one month I added a midday practice period and increased the duration to twenty minutes, which gave me one hour for the day. Thereafter I added five minutes each week until I brought up the time to a single practice period, which amounted to three hours for the day. ... Eventually ... I held the posture for three hours at one time.[29]

He then describes the effects of the practice:

Immediately after standing on my head my breath rate speeded up; then it slowly subsided, and a general feeling of relaxation was experienced. Next came a tendency to restlessness. I had a desire to move my legs in different directions. Soon after this my body became warm and the perspiration began to flow. I was told that this was the measure of my capacity and that I should never try to hold the posture beyond this point.[30]

He is frank about the difficulties:

One of the most trying problems I encountered when building up to the higher time standards was what to do with my mind. The moment I began to feel the slightest fatigue, my mind began to wander. At this point my teacher instructed me to select a spot on a level with my eyes, when standing on my head and direct the attention of my mind to it. Shortly this became a habit, and my mind adapted itself without the least awareness of the passage of time ...[30]

Publication history

editHatha Yoga was first published in the United States in 1943/44, and in the UK in 1950.

The 2007 Harmony Publishing edition is a slim volume of 154 pages, illustrated with 37[f] high-quality monochrome photographs, some of them occupying a full page, the rest half a page each.[31]

Reception

editContemporary

editThe scholar of religion Charles S. Braden, reviewing the book for the Journal of Bible and Religion in 1945, noted that Bernard "became much interested in Oriental religion" and travelled to India and Tibet to experience it first-hand. "He became an adept" of "Hatha Yoga or Bodily Yoga". Braden comments that the book "is superbly illustrated", and that "one cannot but marvel .. at the high degree of body control which the author achieved." He called the text "a complete description of the techniques" and "well-documented from original Indian sources". Braden concluded that Bernard had contributed to the understanding "of this unusual type of religious expression in the West."[32]

Modern

editIn 1999, the yoga scholar-practitioner Norman Sjoman took Bernard's claims at face value, calling the book "a fascinating documentation of hatha yoga or tantric yoga practices", and noting "distinct similarities with the Nath tradition and with ideas that developed in puranic times presumably from the Patanjali tradition." He described it as "virtually the only documentation of a [hatha yoga] practice tradition".[33] Sjoman notes that Bernard was taught the asanas in order to build up his skills of continuous effort and concentration for use in meditation; and that he was instructed to build up the time he could hold each asana until he reached a set threshold, at which point he was allowed to move to the next kind of practice.[34] The threshold indicated that he had become strong enough, physically and psychologically, to cope with the next stage.[34] Sjoman stated that Bernard's was the only documentary evidence of a yoga system actually being followed.[34] As for the Nath yogins and Patanjali, the asanas served "as a medium of exploration of the conscious and unconscious mind",[34] indeed forming "the main vehicle of their doctrine".[34] That was something that Sjoman believed had otherwise been lost. Bernard had not only described the thresholds he was given; he recorded "his own evaluations after successfully completing each practice assigned to him."[34] Finally, Sjoman writes that the photographs of Bernard's asanas could be used as rare evidence that asana practice had evolved in "the most obvious" direction, namely towards increased precision, a direction lately taken up in the modern yoga movement by Iyengar Yoga, with no forerunners other than Bernard's glimpse of an earlier tradition of precision.[34]

In 2010, another yoga scholar-practitioner, Mark Singleton, again accepting Bernard's claims, called Hatha Yoga an influential "participant/observer account of a hatha yoga sādhana", and an "important forerunner of the encyclopedic asana guides of Vishnudevananda (1960) and Iyengar (1966)".[35] He added that it was "rare" for a Westerner's theoretical knowledge of the subtle body with its nadi channels and chakras "to be applied as part of a hatha yoga practice" such as in the traditional texts or as Bernard describes.[36] Singleton notes Bernard's statement that his yoga teacher near Ranchi, India advised him to go and study in Tibet as, in Bernard's words, "what has become mere tradition in India is still living and visible in the ancient monasteries of that isolated land of mysteries".[37][38]

Bernard's biographer, Douglas Veenhof, was more cautious. He noted in his 2011 book White Lama that Bernard "found it necessary to completely conceal his father's role in shaping him as a yogi",[39] instead inventing "a fictional Indian guru whom he described in great detail"[39] but never named, even when pressed. Veenhof remarked that Bernard's account of how he met his guru in Arizona was "like much of his autobiographical writings, a mélange of verifiable fact and pure invention."[39] Veenhof commented that it was ironic that Bernard, sworn to secrecy on his involvement in Tantric rites, wrote about his experiences "at great length"[40] but refused to tell the one thing that teachers of yoga and Buddhism normally publicise to their students: "the lineage of their teachers."[40] His unwillingness to disclose the names of his teachers contributed to the rejection of his dissertation on "Tantric Yoga" in 1938; he eventually rewrote it as Hatha Yoga, the Report of a Personal Experience, which was accepted by Columbia University in 1943, and published by Columbia University Press in a handsome binding embossed with a Tibetan double dorje, complete with its 37 studio photographs, but it still did not reveal the names of his gurus, nor "distinguish his experiences from the theories about them".[41] Veenhof remarked that given that Bernard had not, in fact, benefited from the traditional apprenticeship that he claimed in the book, and that America at that time lacked teachers with that kind of knowledge, "the experimental results that he reports from his self-directed studies are all the more remarkable."[42]

The journalist and historian of American yoga Stefanie Syman wrote in 2010 that Bernard's "most authoritative book" on yoga could reach "only the tiniest audience".[43] By cutting down the complexity to what he considered the essentials, three practices—lotus pose, Uddiyana, and pranayama—he had, in Syman's view, done something like reducing a course in medicine to organic chemistry, molecular biology, and brain surgery: the tasks were fewer but not less difficult. She argued that Bernard, "earnest, ambitious, and proud", relished the challenge of hatha yoga, "his audience be damned", and wanted to show how complex the practice was.[43]

Notes

edit- ^ According to his biographer, Douglas Veenhof, his guru for this training was his father, Glen Bernard, who had travelled in India and had studied under a Syrian-Bengali, Sylvais Hamati.[8]

- ^ Bhramari is the Hindu bee goddess.

- ^ And as a higher-quality the lead image in the article on Bernard

- ^ Siva Samhita 3.10-19 is cited and quoted in a footnote by Bernard.

- ^ Hatha Yoga Pradipika 3.78-81 is cited and quoted in a footnote by Bernard.

- ^ One being the frontispiece.

References

edit- ^ Columbia University 2016.

- ^ Stephens 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Patterson 2013.

- ^ Syman 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Jain 2016.

- ^ Syman 2010, p. 138.

- ^ Bernard 2007, pp. 13–21.

- ^ Veenhof 2011, pp. 17–21.

- ^ a b Bernard 2007, pp. 23–32.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 23.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 24.

- ^ Bernard 2007, pp. 33–48.

- ^ Bernard 2007, pp. 49–62.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 32, 180–181, 228–232.

- ^ Bernard 2007, pp. 63–80.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 90.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 91.

- ^ a b Bernard 2007, p. 100.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 104.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 105.

- ^ Bernard 2007, pp. 24–105.

- ^ Bernard 2007, pp. 107–137.

- ^ Blue Sky 2013.

- ^ a b c d Kunimoto 2011.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 29, footnote, and Plate XXVIII.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 29.

- ^ Bernard 2007, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Bernard 2007, p. 30.

- ^ Bernard 2007.

- ^ Braden 1945.

- ^ Sjoman 1999, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sjoman 1999, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Singleton 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Singleton 2010, p. 32.

- ^ Singleton 2010, p. 213.

- ^ Bernard 2007, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Veenhof 2011, p. 20.

- ^ a b Veenhof 2011, p. 21.

- ^ Veenhof 2011, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Veenhof 2011, p. 320.

- ^ a b Syman 2010, pp. 138–139.

Sources

edit- Bernard, Theos (2007). Hatha Yoga: The Report of A Personal Experience. Harmony. ISBN 978-0-9552412-2-2. OCLC 230987898.

- Braden, Charles S. (1945). "Book Notices: Hatha Yoga. The Report of a Personal Experience. By Theos Bernard". Journal of Bible and Religion. 13 (4): 235. JSTOR 1456235.

- Blue Sky (2013). "Book Review: "The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America," by Stefanie Syman". Slices of Blue Sky.

- Columbia University (2016). "The Life and Works of Theos Bernard". columbia.edu.

- Jain, Andrea (2016). "The Early History of Modern Yoga". 1. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.163. ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Kunimoto, Namiko (2011). "Traveler-as-Lama Photography and the Fantasy of Transformation in Tibet". Trans Asia Photography Review. 2 (1: The Elu[va]sive Portrait: In Pursuit of Photographic Portraiture in East Asia and Beyond, Guest edited by Ayelet Zohar, Fall 2011).

- Mallinson, James; Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.

- Patterson, Bobbi (2013). "Theos Bernard, the White Lama: Tibet, Yoga, and American Religious Life". Practical Matters A Journal of Religious Practices and Practical Theology.

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.

- Sjoman, Norman E. (1999) [1996]. The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace (2nd ed.). Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-389-2.

- Stephens, Mark (2010). Teaching Yoga: Essential Foundations and Techniques. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-885-1.

- Syman, Stefanie (2010). The Subtle Body : the Story of Yoga in America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-53284-0. OCLC 456171421.

- Veenhof, Douglas (2011). White Lama: The Life of Tantric Yogi Theos Bernard, Tibet's Emissary to the New World. Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0385514323.