Wiggins is a city in and the county seat of Stone County, Mississippi, United States.[3] It is part of the Gulfport–Biloxi, Mississippi Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 4,272 at the 2020 census.

Wiggins, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| City of Wiggins | |

Wiggins City Hall in January 2021 | |

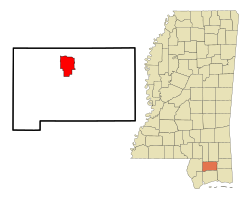

Location of Wiggins, Mississippi | |

| Coordinates: 30°51′20″N 89°8′19″W / 30.85556°N 89.13861°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Stone |

| Area | |

• Total | 11.26 sq mi (29.17 km2) |

| • Land | 10.75 sq mi (27.84 km2) |

| • Water | 0.51 sq mi (1.33 km2) |

| Elevation | 262 ft (80 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 4,272 |

| • Density | 397.40/sq mi (153.44/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 39577 |

| Area code(s) | 601, 769 |

| FIPS code | 28-80160 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2405742[2] |

| Website | www |

History

editWiggins is named after Wiggins Hatten, the father of Madison Hatten, one of the area's original homesteaders.[4] It was incorporated in 1904, and the 1910 census reported 980 residents. In the early 1900s, Wiggins prospered along with the booming timber industry. Wiggins was once headquarters of the Finkbine Lumber Company.

On January 21, 1910, between the hours of 11 am and 1 pm, more than half of the Wiggins business district was destroyed by fire.[5] The fire started from unknown origin in the Hammock Building, a lodging house, and spread rapidly because of strong winds from the northwest. With no city fire department or waterworks, the residents of Wiggins resorted to bucket brigades and dynamite to stop the fire, which was confined to the east side of the Gulf and Ship Island Railroad. The fire consumed 41 business establishments, including the Gulf and Ship Island Railroad depot. Only two or three residential dwellings were destroyed, because most homes were built away from the business district.

Wiggins has long been known for its pickle production, and at one time boasted of being home to the world's largest pickle processing facility.[6] However, the pickle processing facility is now closed, and although the timber industry has declined since the boom years, it still sustains many businesses in Wiggins.

On June 22, 1935, a mob of 200 white people lynched a black man, R. D. McGee. A white girl had been attacked, and McGee was suspected as the culprit. He was roused from his bed, and taken before the girl. She identified him, a day later, based on the clothing her attacker had been wearing.[7] The same day it was reported that Dewitt Armstrong, another African-American was flogged for making insulting remarks to white women.[8][9] On November 21, 1938, another black man, Wilder McGowan, was lynched by a mob of 200 white men for allegedly assaulting a 74-year-old woman. An investigator found there was no merit to the charge against McGowan, but rather that he was lynched because he "Did not know his place,"[10] and in addition had rebuffed a group of white men who had invaded a negro dance hall "looking for some good-looking nigger women". His death certificate indicated strangulation by "rope party".[11] Although seventeen men were identified as participating in the lynching, the justice department decided no action was merited.[12] In 2016, a group of white students at Stone High School put a noose around a black student's neck. The student's parent alleged that local law enforcement discouraged their family from filing a report.[13]

In June 2021, Wiggins voters elected their first African-American mayor, Darrell Berry, who had served as mayor pro temp since November 2020 and then interim mayor since January 2021, following the death of the city's incumbent mayor.[14][15] Berry had been an elected Wiggins alderman during three mayoral terms (12 years) prior to his election as mayor.[15] As of June 2021, the city had three African-Americans simultaneously serving on the city council.[15]

Pine Hill

editAfter the 1910 fire and until the 1960s, the center of commerce for Wiggins developed on both sides of Pine Avenue, that sloped downhill and eastward, perpendicular to U.S. Route 49 and Railroad Street (First Street), over a distance of one city block. Small shops were built mainly of brick and were mostly contiguous to each other. Over the years, the shops were occupied by numerous businesses that included drug stores, law offices, a grocery store, a shoe store, a dry cleaners, 5 & dime stores, auto supply store, barber shops, cafes, a movie theater, dry goods outlet, feed & seed outlet, an army surplus store, beauty salons, clothing stores, gift shops, County Library, and U.S. Post Office. In more recent years, the shops have served as real estate offices, CPA & tax preparer outlets, an antique store, newspaper office, ice cream shop, art & frame shop, food outlets, and stationery shop.

In the late 1960s, U.S. Route 49 bypassed the downtown area, and many businesses moved from Pine Hill to other locations within Wiggins. The old Wiggins High School and Elementary School buildings occupied a city block, situated at the base of Pine Hill. When the school buildings were demolished in the 1970s, the school land was dedicated to City use as Blaylock Park. In the 1980s, city and county business leaders saw a need for developing a sense of community and tourism by initiating an annual Pine Hill Day, which later became Pine Hill Festival.[16] During Pine Hill Day, area residents offered items for sale as arts & crafts, in farmers' markets, and as local cuisine. To attract more visitors, other venues such as live music entertainment, competitive foot races, antique vehicle displays, commercial food vendors, and games for kids were added through the years, and the festival became a Spring event. In 2014, an estimated 15,000 people attended the 2-day festival.[17]

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 11.3 square miles (29 km2), of which, 10.8 square miles (28 km2) of it is land and 0.5 square miles (1.3 km2) of it (4.53%) is water. The entrance to Flint Creek Water Park is located in the city, off Highway 29.

Climate

edit| Climate data for Wiggins, Mississippi (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1946–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

85 (29) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

100 (38) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

108 (42) |

101 (38) |

96 (36) |

89 (32) |

87 (31) |

108 (42) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 61.6 (16.4) |

65.6 (18.7) |

72.6 (22.6) |

78.5 (25.8) |

84.7 (29.3) |

90.6 (32.6) |

91.5 (33.1) |

91.5 (33.1) |

87.9 (31.1) |

80.2 (26.8) |

70.3 (21.3) |

63.8 (17.7) |

78.2 (25.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 48.9 (9.4) |

52.9 (11.6) |

59.2 (15.1) |

65.4 (18.6) |

72.6 (22.6) |

79.2 (26.2) |

80.9 (27.2) |

80.9 (27.2) |

76.7 (24.8) |

67.3 (19.6) |

57.2 (14.0) |

51.6 (10.9) |

66.1 (18.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 36.2 (2.3) |

40.1 (4.5) |

45.9 (7.7) |

52.2 (11.2) |

60.4 (15.8) |

67.8 (19.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

70.3 (21.3) |

65.5 (18.6) |

54.5 (12.5) |

44.1 (6.7) |

39.4 (4.1) |

53.9 (12.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 1 (−17) |

7 (−14) |

15 (−9) |

29 (−2) |

39 (4) |

48 (9) |

54 (12) |

56 (13) |

37 (3) |

25 (−4) |

18 (−8) |

7 (−14) |

1 (−17) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.05 (154) |

5.30 (135) |

5.86 (149) |

5.46 (139) |

5.51 (140) |

5.90 (150) |

7.28 (185) |

6.12 (155) |

5.89 (150) |

3.95 (100) |

4.12 (105) |

5.92 (150) |

67.36 (1,711) |

| Source: NOAA[18][19] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 980 | — | |

| 1920 | 1,037 | 5.8% | |

| 1930 | 1,074 | 3.6% | |

| 1940 | 1,141 | 6.2% | |

| 1950 | 1,436 | 25.9% | |

| 1960 | 1,591 | 10.8% | |

| 1970 | 2,995 | 88.2% | |

| 1980 | 3,205 | 7.0% | |

| 1990 | 3,185 | −0.6% | |

| 2000 | 3,849 | 20.8% | |

| 2010 | 4,390 | 14.1% | |

| 2020 | 4,272 | −2.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[20] 2012 Estimate[21] | |||

| Race | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| White | 2,661 | 62.29% |

| Black or African American | 1,348 | 31.55% |

| Native American | 15 | 0.35% |

| Asian | 26 | 0.61% |

| Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.02% |

| Other/Mixed | 145 | 3.39% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 76 | 1.78% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 4,272 people, 1,348 households, and 889 families residing in the city.

Education

edit- The City of Wiggins is served by the Stone County School District.

- Gateway Christian Academy (A private school, serving Nursery/Preschool–12.)[23]

Media

edit- Stone County Enterprise,[24] "Your hometown newspaper since 1916"

- Wiggins is part of Mississippi Gulf Coast Radio and Television Stations Market Area

Infrastructure

edit- Airport: Dean Griffin Memorial Airport[25]

- Highways: U.S. Highway 49, Mississippi Highway 26, Mississippi Highway 29

- Railroad: Kansas City Southern Railroad

Notable people

edit- William Joel Blass, attorney and educator[26]

- Chris Boykin, CEO of Big Black Inc.[27]

- Sammy Brown, professional football player

- Jay Hanna "Dizzy" Dean, professional baseball player and radio personality, lived in the nearby Bond community[28]

- Justin Evans, professional football player[29]

- Anthony Herrera, actor, soap opera star[30]

- Marcus Hinton, gridiron football player[31]

- Boyce Holleman, attorney and actor[32]

- Rebekah Jones, whistleblower[33] whose claims the Office of Inspector General later found to be unsubstantiated or unfounded; those she accused were exonerated of any misconduct.[34]

- Fred Lewis, former Cincinnati Reds outfielder[35]

- Stevon Moore, retired from NFL Cleveland Browns and Baltimore Ravens[36]

- Taylor Spreitler, actress[37]

- Emilie Blackmore Stapp, author and philanthropist[38]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Wiggins, Stone County, Mississippi

- ^ "Stone County, MS". County Explorer. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ "Stone County Economic Development Partnership". Archived from the original on July 17, 2009. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ "Wiggins, MS fire, Jan 1910 | GenDisasters ... Genealogy in Tragedy, Disasters, Fires, Floods". Gendisasters.com. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ Kat Bergeron. 2012. Green Gold: The story of the Wiggins pickle. Sun Herald (Biloxi, MS), Vol. 128, No. 230, Page 8F, May 20, 2012.

- ^ "Mob Hangs Man for Attempted Attack on Girl". Stone County Enterprise. Wiggins, Mississippi. June 27, 1935. Retrieved December 23, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Negro Flogged". Stone County Enterprise. Wiggins, Mississippi. June 27, 1935. Retrieved December 23, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Negro is Lynched, Another Whipped". New York Times. June 23, 1935.

- ^ "Mob Uses Attack Rumor as Excuse to Slay Man who Wouldn't 'Knuckle'". Chicago Defender. December 17, 1938.

- ^ "Standard Certificate of Death" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ "Wilder McGowan". Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ Hawkins, Derek (October 25, 2016). "White high schoolers in Miss. put noose around black student's neck and 'yanked,' NAACP says". Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ^ Berryhill, Lyndy (January 7, 2021). "Wiggins appoints Darryl Berry as Interim Mayor". Stone County Enterprise. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c Berryhill, Lyndy (June 16, 2021). "Berry elected Mayor". Stone County Enterprise. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ "Stone County Economic Development Partnership". Archived from the original on October 18, 2010. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ Patrick Ochs. 2014. Record crowds fill Wiggins for festival. Sun Herald (Biloxi, MS), Vol. 130, No. 171, Page 2A, March 23, 2014.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Census.gov. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ "Gateway Christian Academy Profile (2020) | Wiggins, MS". Private School Review. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Home". Stone County Enterprise. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "M24 - Dean Griffin Memorial Airport". AirNav. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "The Clinton Courier, William Joel Blass". Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ "Big Black and Bam Bam | The Locker Room". Lockerroommag.com. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "Dean, Dizzy - Dictionary definition of Dean, Dizzy | Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "Justin Evans of Wiggins drafted in the second round of the NFL Draft by Tampa Bay". wlox.com. April 29, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ "Anthony Herrera". Stonecountyenterprise.com. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Attorney Boyce Holleman Remembered By Sons with $100,000 Gift to Law School". News.olemiss.edu. April 13, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ Berryhill, Lyndy (December 16, 2020). Fla. health official accused of being 'whistleblower' is a Stone High graduate. Stone County Enterprise

- ^ Bustos, Sergio; Kennedy, John. "State investigators dismiss Rebekah Jones's claims of Florida fudging COVID-19 data". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ "Fred Lewis Stats". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "Stevon Moore Stats". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "Taylor Spreitler biography". IMDb.com. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "Exploring the life and the legacy of Emilie Blackmore Stapp (1876-1962) | National Endowment for the Humanities". Neh.gov. March 15, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2017.