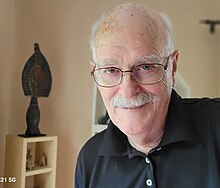

Arthur Palmer Arnold (born March 16, 1946) is an American biologist who specializes in sex differences in physiology and disease, genetics, neuroendocrinology, and behavior. He is Distinguished Professor of Integrative Biology & Physiology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). His research has included the discovery of large structural sex differences in the central nervous system, and he studies of how gonadal hormones and sex chromosome genes cause sex differences in numerous tissues. His research program has suggested revisions to concepts of mammalian sexual differentiation and forms a foundation for understanding sex difference in disease.[1] Arnold was born in Philadelphia.

Career

editSource:[1]

Arnold received an A.B. degree in Psychology from Grinnell College (1967) and Ph.D. in Neurobiology and Behavior from The Rockefeller University (1974), where he was mentored by Fernando Nottebohm, Peter Marler, Donald Pfaff, Bruce McEwen and Hiroshi Asanuma.[2] Since 1976 he has been on the faculty at UCLA, serving as Associate Director of the UCLA Brain Research Institute (1989-2001), Chair of the Department of Integrative Biology & Physiology (2001-2009), and Director of the UCLA Laboratory of Neuroendocrinology of the Brain Research Institute (2001-2017). Arnold was the inaugural President of the Society for Behavior Neuroendocrinoloogy (1997-1999). Arnold co-founded the Organization for the Study of Sex Differences (OSSD, 2006, https://www.ossdweb.org/founders) and was Founding Editor-in-Chief of the OSSD’s official journal, Biology of Sex Differences (2010-2018).

Research

editIn 1976, Fernando Nottebohm and Arnold reported the first example of large morphological sex differences in the brain of any vertebrate, in the neural circuit controlling singing in passerine birds. The report triggered a reevaluation of the magnitude and significance of biological sex differences in the structure and function of the brain, including in humans.[3][4][5][6] The report inspired the discovery of numerous other structural sex differences in the brains of other vertebrate species such as humans and other mammals.[7][8][1] The identification of groups of cells that differed, in specific brain regions of males and females, moved the study of sexual differentiation to the cellular and molecular level, ultimately enabling the discovery of the molecular mechanisms of sexual differentiation in the brain. Arnold and co-workers uncovered hormonal control of cellular mechanisms (cell death, dendritic growth, cell growth, synapse elimination) that cause differential nervous system development in males and females.[9]

Arnold's study of a gynandromorphic (half genetic male, half genetic female) zebra finch suggested that not all sex differences in brain and behavior are caused by gonadal hormones, as had been believed.[1] The two sides of the gynandromorph brain differed in the degree of masculinity of the neural song circuit, implying that sex chromosomes operated within brain cells to contribute to sex differences.[10][11] Arnold and collaborators used several mouse models (e.g, “Four Core Genotypes”) to show that mice with different sex chromosomes (XX vs. XY) have large sex differences caused by sex chromosomes, not by gonadal hormones; the sex chromosomes affect models of diverse diseases (autoimmune, metabolic, cardiovascular, cancer, neural and behavioral). Arnold’s research shifted the concepts for understanding the biological differences between the sexes,[12][13] and contributed to the rationale for the US National Institutes of Health to increase focus on sex differences in preclinical research.[14] It also led to the discovery of specific X and Y genes that cause sex differences in mouse models of disease, therefore increasing understanding of sex-biasing functions of genes on the mammalian X and Y chromosome.[15][16]

Arnold has mentored 13 Ph.D. students, 24 postdoctoral fellows, and 6 M.S. students.

Awards and Honors

edit- Phi Beta Kappa, 1966

- Fellow, John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, 1998

- Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1998

- Inaugural President, Society for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology, 1997-1999, https://sbn.org/about/presidents.aspx

- Daniel S. Lehrman Lifetime Achievement Award from Society for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology, 2010, https://sbn.org/awards/daniel-s-lehrman-award.aspx

- Frank Beach Lecture, University of California, Berkeley, 1988

- Magoun Lecture, UCLA Brain Research Institute, 2003

- Robert Goy Lecture, University of Wisconsin Primate Center, 2016

- Charles Sawyer Distinguished Lecture, UCLA, 2019

- Arthur Arnold Lecture established in 2018 by Organization for the Study of Sex Differences

- Arthur Arnold Innovator Lecture established in 2019 by the Laboratory of Neuroendocrinology of the UCLA Brain Research Institute.

Notable Publications

edit- Nottebohm, Fernando; Arnold, Arthur P. (8 October 1976). "Sexual Dimorphism in Vocal Control Areas of the Songbird Brain". Science. 194 (4261): 211–213. Bibcode:1976Sci...194..211N. doi:10.1126/science.959852. PMID 959852.

- Breedlove, S. Marc; Arnold, Arthur P. (31 October 1980). "Hormone Accumulation in a Sexually Dimorphic Motor Nucleus of the Rat Spinal Cord". Science. 210 (4469): 564–566. Bibcode:1980Sci...210..564B. doi:10.1126/science.7423210. PMID 7423210.

- Nottebohm, Fernando; Arnold, Arthur P. (8 October 1976). "Sexual Dimorphism in Vocal Control Areas of the Songbird Brain". Science. 194 (4261): 211–213. Bibcode:1976Sci...194..211N. doi:10.1126/science.959852. PMID 959852.

- McCarthy, Margaret M; Arnold, Arthur P (June 2011). "Reframing sexual differentiation of the brain". Nature Neuroscience. 14 (6): 677–683. doi:10.1038/nn.2834. PMC 3165173. PMID 21613996.

- Agate, Robert J.; Grisham, William; Wade, Juli; Mann, Suzanne; Wingfield, John; Schanen, Carolyn; Palotie, Aarno; Arnold, Arthur P. (15 April 2003). "Neural, not gonadal, origin of brain sex differences in a gynandromorphic finch". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (8): 4873–4878. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.4873A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0636925100. PMC 153648. PMID 12672961.

- Itoh, Yuichiro; Melamed, Esther; Yang, Xia; Kampf, Kathy; Wang, Susanna; Yehya, Nadir; Van Nas, Atila; Replogle, Kirstin; Band, Mark R; Clayton, David F; Schadt, Eric E; Lusis, Aldons J; Arnold, Arthur P (2007). "Dosage compensation is less effective in birds than in mammals". Journal of Biology. 6 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/jbiol53. PMC 2373894. PMID 17352797.

- Arnold, Arthur P. (February 2012). "The end of gonad-centric sex determination in mammals". Trends in Genetics. 28 (2): 55–61. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2011.10.004. PMC 3268825. PMID 22078126.

- Arnold, Arthur P. (2 January 2017). "A general theory of sexual differentiation". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 95 (1–2): 291–300. doi:10.1002/jnr.23884. PMC 5369239. PMID 27870435.

- Arnold, Arthur P. (December 2020). "Four Core Genotypes and XY* mouse models: Update on impact on SABV research". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 119: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.09.021. PMC 7736196. PMID 32980399.

- Arnold, Arthur P. (September 2022). "X chromosome agents of sexual differentiation". Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 18 (9): 574–583. doi:10.1038/s41574-022-00697-0. PMC 9901281. PMID 35705742.

References

edit- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Schlinger BA (2022). "Arthur P. Arnold". In Nelson, RJ; Weil, ZM (eds.). Biographical History of Behavioral Neuroendocrinology. Springer Verlag.

- ^ Mackel, R; Pavlides, C (2000). "Hiroshi Asanuma (1926-2000)". NeuroReport. 11 (15): A5–6. PMID 11059891.

- ^ "Cover story: The sexes: how they differ and why". Newsweek. May 18, 1981.

- ^ "Landmark Papers". Journal of NIH Research. 7: 28–33, 52–58. 1995.

- ^ Schmeck, Harold M. (25 March 1980). "Brains May Differ In Women And Men; Brain Differences". The New York Times.

- ^ Harding, C (2004). "Learning from Bird Brains: How the Study of Songbird Brains Revolutionized Neuroscience". Lab Animal. 33 (5): 28–33. doi:10.1038/laban0504-28. PMID 15141244. S2CID 751995.

- ^ Gorski, Roger A. (June 1985). "The 13th J. A. F. Stevenson Memorial Lecture Sexual differentiation of the brain: possible mechanisms and implications". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 63 (6): 577–594. doi:10.1139/y85-098. PMID 4041997.

- ^ Breedlove , SM (1992). "Sexual Differentiation of the Brain and Behavior". In Becker, JB; Breedlove, SM; Crews, D (eds.). Behavioral Endocrinology. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. pp. 39–68.

- ^ Sengelaub, Dale R.; Forger, Nancy G. (May 2008). "The spinal nucleus of the bulbocavernosus: Firsts in androgen-dependent neural sex differences". Hormones and Behavior. 53 (5): 596–612. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.11.008. PMC 2423220. PMID 18191128.

- ^ Weintraub, Karen (25 February 2019). "Split-Sex Animals Are Unusual, Yes, but Not as Rare as You'd Think". The New York Times.

- ^ Ainsworth, Claire (October 2017). "Sex and the single cell". Nature. 550 (7674): S6–S8. doi:10.1038/550S6a. PMID 28976954.

- ^ Ainsworth, Claire (1 February 2015). "Sex redefined". Nature. 518 (7539): 288–291. Bibcode:2015Natur.518..288A. doi:10.1038/518288a. PMID 25693544.

- ^ Schlinger, Barney A.; Carruth, Laura; de Vries, Geert J.; Xu, Jun (June 2011). "State-of-the art (Arnold) behavioral neuroendocrinology". Hormones and Behavior. 60 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.11.009. PMID 21658535. S2CID 9785591.

- ^ Clayton, Janine A.; Collins, Francis S. (May 2014). "Policy: NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies". Nature. 509 (7500): 282–283. doi:10.1038/509282a. PMC 5101948. PMID 24834516.

- ^ Dance, A (March 4, 2020). "Genes that escape silencing on the second X chromosome may drive disease". The Scientist.

- ^ Arnold, Arthur P. (September 2022). "X chromosome agents of sexual differentiation". Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 18 (9): 574–583. doi:10.1038/s41574-022-00697-0. PMC 9901281. PMID 35705742.