East Asian Buddhism or East Asian Mahayana is a collective term for the schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism that developed across East Asia and which rely on the Chinese Buddhist canon. These include the various forms of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese Buddhism in East Asia.[1][2][3][4] East Asian Buddhists constitute the numerically largest body of Buddhist traditions in the world, numbering over half of the world's Buddhists.[5][6]

East Asian forms of Buddhism all derive from sinicized Buddhist schools that developed during the Han dynasty and the Song dynasty, and therefore are influenced by Chinese culture and philosophy.[7][8] The spread of Buddhism to East Asia was aided by the trade networks of the Silk Road and the missionary work of generations of Indian and Asian Buddhists. Some of the most influential East Asian traditions include Chan (Zen), Nichiren Buddhism, Pure Land, Huayan, Tiantai, and Chinese Esoteric Buddhism.[9] These schools developed new, uniquely East Asian interpretations of Buddhist texts and focused on the study of Mahayana sutras. According to Paul Williams, this emphasis on the study of the sutras contrasts with the Tibetan Buddhist attitude which sees the sutras as too difficult unless approached through the study of philosophical treatises (shastras).[10]

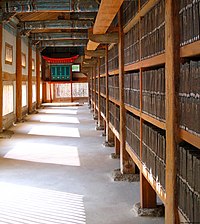

The texts of the Chinese Buddhist Canon began to be translated in the second century and the collection continued to evolve over a period of a thousand years with the first woodblock printed edition being published in 983. A major modern edition of this canon is the Taishō Tripiṭaka, produced in Japan between 1924 and 1932.[11] Besides sharing a canon of scripture, the various forms of East Asian Buddhism have also adapted East Asian values and practices which were not prominent in Indian Buddhism, such as Chinese ancestor veneration and the Confucian view of filial piety.[12]

East Asian Buddhist monastics generally follow the monastic rule known as the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya.[13] One major exception is some schools of Japanese Buddhism where Buddhist clergy sometimes marry, without following the traditional monastic code or Vinaya. This developed during the Meiji Restoration, when a nationwide campaign against Buddhism forced certain Japanese Buddhist sects to change their practices.[14]

Buddhism in East Asia

editBuddhism in China

editBuddhism in China has been characterized by complex interactions with China's indigenous religious traditions, Taoism and Confucianism, and varied between periods of institutional support and repression from governments and dynasties. Buddhism was first introduced to China during the Han dynasty, at a time when the Han empire expanded its nascent corresponding geopolitical influence into the reaches of Central Asia.[15] Opportunities for vibrant cultural exchanges and trade contacts along the Silk Road and sea trade routes with the Indian subcontinent and maritime Southeast Asia made it inevitable that the percolation of Buddhism would penetrate into China and gradually into the rest of East Asia at large.[16] Such religious transmissions were able to be afforded to enable the inexorable percolation of Buddhism into East Asia over a millennia due to the vibrant cultural exchanges that were able to be made at that time as a result of the Silk Road.[17][4]

Chinese Buddhism has strongly influenced the development of Buddhism in other East Asian countries, with the Chinese Buddhist Canon serving as the primary religious texts for other countries in the region.[18][4]

Early Chinese Buddhism was influenced by translators from Central Asia who began the translation of large numbers of Tripitaka and commentarial texts from India and Central Asia into Chinese. Early efforts to organize and interpret the wide range of texts received gave rise to early Chinese Buddhist schools like the Huayan and Tiantai schools.[19][20] In the 8th century, the Chan school began to emerge, eventually becoming the most influential Buddhist school in East Asia and spreading throughout the region.[21]

Buddhism in Japan

editBuddhism was officially introduced to Japan from China and Korea during the 5th and 6th centuries AD.[22] In addition to developing their own versions of Chinese and Korean traditions (such as Zen, a Japanese form of Chan and Shingon, a form of Chinese Esoteric Buddhism), Japan developed their own indigenous traditions like Tendai, based on the Chinese Tiantai, Nichiren, and Jōdo Shinshū (a Pure Land school).[23][24]

Buddhism in Korea

editBuddhism was introduced to Korea from China during the 4th century, where it began to be practiced alongside indigenous shamanism.[25] Following strong state support in the Goryeo era, Buddhism was suppressed during the Joseon period in favor of Neo-Confucianism.[26] Suppression was finally ended due to Buddhist participation in repelling the Japanese invasion of Korea in the 16th century, leading to a slow period of recovery that lasted into the 20th century. The Seon school, derived from Chinese Chan Buddhism, was introduced in the 7th century and grew to become the most widespread form of modern Korean Buddhism, with the Jogye Order and Taego Order as its two main branches.

Buddhism in Vietnam

editBordering southern China, Buddhism may have first come to Vietnam as early as the 3rd or 2nd century BCE from the Indian subcontinent or from China in the 1st or 2nd century CE. [27][28] Vietnamese Buddhism was influenced by certain elements of Taoism, Chinese spirituality, and Vietnamese folk religion. [29]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Charles Orzech (2010), Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 3-4.

- ^ "East Asian Buddhism and Nature (ERN) — Faculty/Staff Sites". www.uwosh.edu. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ Anderl, Christoph (2011). Zen Buddhist Rhetoric in China, Korea, and Japan. Brill Publishers. p. 85. ISBN 978-9004185562.

- ^ a b c Jones, Charles B. (2021). Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice, p. xii. Shambhala Publications, ISBN 978-1611808902.

- ^ Pew Research Center, Global Religious Landscape: Buddhists.

- ^ Johnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J. (2013). The World's Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography (PDF). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 34. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Gethin, Rupert, The Foundations of Buddhism, OUP Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 257.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 275. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 275. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Williams, Paul, Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations, Taylor & Francis, 2008, P. 129.

- ^ Gethin, Rupert, The Foundations of Buddhism, OUP Oxford, 1998, p. 258.

- ^ Harvey, Peter, An Introduction to Buddhism, Second Edition: Teachings, History and Practices (Introduction to Religion) 2nd Edition, p. 212.

- ^ Gethin, Rupert, The Foundations of Buddhism, OUP Oxford, 1998, p. 260

- ^ Jaffe, Richard (1998). "Meiji Religious Policy, Soto Zen and the Clerical Marriage Problem". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 24 (1–2): 46. Archived from the original on November 19, 2014.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 275. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 275. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 275. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 315. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 278. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 284. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 286. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 310–311. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 315–316. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 319. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 333. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Kitagawa, Joseph (2002). The Religious Traditions of Asia : Religion, History, and Culture. Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 338–339. ISBN 978-0700717620.

- ^ Cuong Tu Nguyen. Zen in Medieval Vietnam: A Study of the Thiền Uyển Tập Anh. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997, pg 9.

- ^ Nguyen Tai Thu. The History of Buddhism in Vietnam. 2008.

- ^ Cuong Tu Nguyen & A.W. Barber 1998, pg 132.

Further reading

edit- Anderl, Christoph (2011). Zen Buddhist Rhetoric in China, Korea, and Japan. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9004185562.

- Jones, Charles B. (2021). Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-1611808902.

- Orzech, Charles (2010). Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9004184916.

- Poceski, Mario (2014). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to East and Inner Asian Buddhism. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118610336.