East Asian Canadians are Canadians who were either born in or can trace their ancestry to East Asia. East Asian Canadians are also a subgroup of Asian Canadians. According to Statistics Canada, East Asian Canadians are considered visible minorities and can be further divided by on the basis of both ethnicity and nationality, such as Chinese Canadian, Hong Kong Canadian, Japanese Canadian, Korean Canadian, Mongolian Canadian, Taiwanese Canadian, or Tibetan Canadian, as seen on demi-decadal census data.

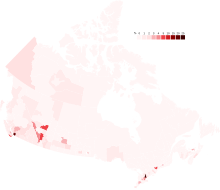

East Asian ancestry % in Canada (2021) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,288,775[1][2][a][b] 6.3% of the total Canadian population (2021) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Southern Ontario, Metro Vancouver, Central Alberta, Montreal | |

| Languages | |

| Canadian English · Canadian French · Mandarin · Cantonese · Korean · Japanese · Mongolian · Min Nan · Tibetan Other East Asian Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism · Chinese folk religion · Christianity · Confucianism · Shintoism · Taoism · Irreligion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| East Asian diaspora |

According to the 2021 Canadian census, 2,288,775 Canadians had trace their ancestry to East Asia, constituting 6.3 percent of the total population and 31.2 percent of the total Asian Canadian population.[1][2][a][b] Additionally as of 2021, East Asians comprise the third largest pan-ethnic group in Canada after Europeans (69.8 percent)[3] and South Asians (7.1 percent).[2]

Terminology

editFor Canadian government census purposes and contemporary Canadian parlance, East Asian Canadians are typically identified and referred under the term "Asian"; popular usage of this term in Canada generally excludes both South and West Asians, both groups with ancestral origins in the Middle East and in the Indian subcontinent respectively, and instead solely referring to individuals who trace their ancestry to the East Asian mainland.

History

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 1,314,225 | — |

| 2006 | 1,628,260 | +23.9% |

| 2011 | 1,817,590 | +11.6% |

| 2016 | 2,148,230 | +18.2% |

| 2021 | 2,288,775[a] | +6.5% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [1][2][4][5][6][7] | ||

18th century

editThe first record of East Asians in what is known as Canada today can be dated back to 1788 when renegade British Captain John Meares hired a group of Chinese carpenters from Macau and employed them to build a ship at Nootka Sound, Vancouver Island, British Columbia. After the outpost was seized by Spanish forces, the eventual whereabouts of the carpenters was largely unknown.

19th century

editIn the mid-late 19th century, early settlers from East Asia, namely China and Japan, emigrated to Canada, predominantly settling in the province of British Columbia.

During the mid-19th century, many Chinese arrived to take part in the British Columbia gold rushes. Beginning in 1858, early settlers formed Victoria's Chinatown and other Chinese communities in New Westminster, Yale, and Lillooet. Estimates indicate that about 1/3 of the non-native population of the Fraser goldfields was Chinese.[8][9] Later, the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway prompted another wave of immigration from China. Mainly hailing from Guangdong, the Chinese helped build the Canadian Pacific Railway through the Fraser Canyon.

Many Japanese people also arrived in Canada during the mid to late 19th century and became fishermen and merchants in British Columbia. Early immigrants from Japan most notably worked in canneries such as Steveston along the pacific coast.

By 1884, Nanaimo, New Westminster, Yale, and Victoria had the largest Chinese populations in the province. Other settlements such as Quesnelle Forks were majority Chinese and many early immigrants from there settled on Vancouver Island, most notably in Cumberland.[10] In addition to work on the railway, most Chinese in the late 19th century British Columbia lived among other Chinese and worked in market gardens, coal mines, sawmills, and salmon canneries.[11]

In 1885, soon after the construction on the railway was completed, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act, whereby the government began to charge a substantial head tax for each Chinese person trying to immigrate to Canada. A decade later, the fear of the "Yellow Peril" prompted the government of Mackenzie Bowell to pass an act forbidding any East Asian Canadian from voting or holding office.[12]

Many Chinese workers settled in Canada after the railway was constructed, however most could not bring the rest of their families, including immediate relatives, due to government restrictions and enormous processing fees. They established Chinatowns and societies in undesirable sections of the cities, such as East Pender Street in Vancouver, which had been the focus of the early city's red-light district until Chinese merchants took over the area from the 1890s onwards.[13]

20th century

editImmigration restrictions stemming from anti-East Asian sentiment in Canada continued during the early 20th century. Parliament voted to increase the Chinese head tax to $500 in 1902; this temporarily caused Chinese immigration to Canada to stop. However, in following years, Chinese immigration to Canada recommenced as many saved up money to pay the head tax.

Heightened anti-East Asian sentiment resulted in the infamous anti-East Asian pogrom in Vancouver in 1907. Spurred by similar riots in Bellingham targeting Punjabi Sikh South Asian settlers, the Asiatic Exclusion League organized attacks against homes and businesses owned by East Asian immigrants under the slogan "White Canada Forever!"; though no one was killed, much property damage was done and numerous East Asian Canadians, namely Chinese and Japanese Canadians were beaten up.

In 1923, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which banned all Chinese immigration, and led to immigration restrictions for all East Asians. In 1947, the act was repealed.

According to the 1931 Canadian census, subdivisions including Richmond (East Asians formed 40 percent of the total population), Skeena Coast (37 percent), Fraser Mills (34 percent), Cumberland (32 percent), Maple Ridge (27 percent), West Vancouver Island (27 percent), Mission (24 percent), Bella Coola Coast (24 percent), Duncan (18 percent), and Pitt Meadows (17 percent) had the largest East Asian concentrations in British Columbia.[14]: 482

| Subdivision | Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Percentage | ||

| Vancouver | Urban | 21,339 | 8.65% |

| Victoria | Urban | 3,999 | 10.23% |

| Richmond | Urban | 3,262 | 39.87% |

| Maple Ridge | Urban | 1,351 | 27.39% |

| South Vancouver Island | Rural | 1,315 | 8.56% |

| New Westminster | Urban | 1,200 | 6.85% |

| Skeena Coast | Rural | 955 | 36.96% |

| Mission | Urban | 868 | 24.16% |

| Bella Coola Coast | Rural | 865 | 24.11% |

| Upper Okanagan & Shuswap | Rural | 809 | 9.17% |

| Cumberland | Urban | 769 | 32.43% |

| West Vancouver Island | Rural | 614 | 26.92% |

| Surrey | Urban | 596 | 7.11% |

| Delta | Urban | 567 | 15.29% |

| Howe Sound | Rural | 529 | 10.96% |

| South East Coast Vancouver Island | Rural | 523 | 9.81% |

| Nicola | Rural | 475 | 8.26% |

| North Cowichan | Urban | 449 | 13.64% |

| North East Coast Vancouver Island | Rural | 442 | 6.08% |

| Saanich | Urban | 432 | 3.33% |

| Nanaimo | Urban | 420 | 6.49% |

| Prince Rupert | Urban | 390 | 6.14% |

| Duncan | Urban | 337 | 18.29% |

| Kamloops | Urban | 329 | 5.33% |

| Kelowna | Urban | 322 | 6.92% |

| North Vancouver Island | Rural | 279 | 11.08% |

| Burnaby | Urban | 266 | 1.04% |

| Saltspring & Islands | Rural | 266 | 9.65% |

| Knight Inlet Coast | Rural | 228 | 17.18% |

| Vernon | Urban | 218 | 5.54% |

| Port Alberni | Urban | 217 | 9.21% |

| Fraser Mills | Urban | 210 | 34.09% |

| Matsqui | Rural | 200 | 5.22% |

| Powell River Coast | Rural | 195 | 3.21% |

| Nelson | Urban | 176 | 2.94% |

| Coquitlam | Urban | 175 | 3.59% |

| Upper Kootenay River | Rural | 173 | 2.27% |

| Portland Canal-Nass | Rural | 167 | 6.18% |

| Similkameen River | Rural | 154 | 2.48% |

| Lower Fraser Valley | Rural | 151 | 3.2% |

| Port Moody | Urban | 155 | 12.3% |

| Cranbrook | Urban | 147 | 4.79% |

| Pitt Meadows | Urban | 145 | 17.43% |

| North Vancouver | Rural | 126 | 2.63% |

| Chilliwack | Rural | 119 | 2.05% |

| Armstrong | Urban | 107 | 10.82% |

| Revelstoke | Urban | 106 | 3.87% |

| Trail | Urban | 102 | 1.35% |

| Upper Columbia River | Rural | 93 | 2.34% |

| Kootenay & Slocan Lakes | Rural | 91 | 0.95% |

| Summerland | Urban | 88 | 4.91% |

| Langley | Urban | 86 | 1.55% |

| West Vancouver | Urban | 86 | 1.8% |

| University Endowment Area | Urban | 83 | 14.43% |

| Coldstream | Urban | 78 | 9% |

| Prince George | Urban | 77 | 3.11% |

| Cariboo | Rural | 75 | 3.97% |

| North Thompson | Rural | 74 | 3.24% |

| Oak Bay | Urban | 73 | 1.24% |

| Chilliwack | Urban | 68 | 2.76% |

| North Columbia River | Rural | 65 | 3.4% |

| Bridge-Lillooet | Rural | 62 | 3.39% |

| Shuswap | Rural | 62 | 1.36% |

| Penticton | Urban | 60 | 1.29% |

| Spallumcheen | Urban | 52 | 3.19% |

| Merritt | Urban | 48 | 3.7% |

| Skeena-Bulkley | Rural | 42 | 1.61% |

| North Vancouver | Urban | 39 | 0.46% |

| Quesnel | Urban | 39 | 8.74% |

| Kent | Urban | 35 | 2.9% |

| Elk & Flathead Rivers | Rural | 35 | 0.73% |

| South Columbia River | Rural | 34 | 0.47% |

| Rossland | Urban | 33 | 1.16% |

| Salmon Arm | Urban | 33 | 3.98% |

| Kaslo | Urban | 32 | 6.12% |

| Port Coquitlam | Urban | 32 | 2.44% |

| Kettle River | Rural | 27 | 0.81% |

| North Coast | Rural | 27 | 8.88% |

| Courtenay | Urban | 26 | 2.13% |

| Fernie | Urban | 25 | 0.92% |

| Queen Charlotte Islands | Rural | 25 | 2.69% |

| Salmon Arm | Rural | 25 | 1.5% |

| Smithers | Urban | 25 | 2.5% |

| Esquimalt | Urban | 23 | 0.7% |

| South Chilcotin | Rural | 20 | 8.77% |

| Ladysmith | Urban | 18 | 1.25% |

| Kiskatinaw River | Rural | 15 | 0.32% |

| Sumas | Urban | 15 | 0.83% |

| Glenmore | Urban | 14 | 4.62% |

| North Chilcotin | Rural | 14 | 1.98% |

| Nechako-Fraser-Parsnip | Rural | 12 | 0.46% |

| Abbotsford | Urban | 10 | 1.96% |

| Creston | Urban | 10 | 1.44% |

| East Lillooet | Rural | 10 | 1% |

| Grand Forks | Urban | 10 | 0.77% |

| Hope | Urban | 9 | 2.41% |

| Enderby | Urban | 8 | 1.44% |

| Terrace | Urban | 8 | 2.27% |

| Williams Lake | Urban | 8 | 1.99% |

| Alberni | Urban | 7 | 1% |

| Stikine-Liard | Rural | 7 | 2.33% |

| Atlin Lake | Rural | 5 | 1.02% |

| Burns Lake | Urban | 5 | 2.48% |

| Fraser-Canoe | Rural | 5 | 0.21% |

| Vanderhoof | Urban | 5 | 1.64% |

| Upper Nechako | Rural | 3 | 0.16% |

| Babine-Stuart-Takla Lakes | Rural | 2 | 0.32% |

| Beaton River | Rural | 2 | 0.12% |

| Silverton | Urban | 2 | 0.74% |

| Tadanac | Urban | 2 | 0.43% |

| Greenwood | Urban | 1 | 0.58% |

| British Columbia | Total | 49,344 | 7.11% |

World War II prompted the federal government used the War Measures Act to brand Japanese Canadians enemy aliens and categorized them as security threats in 1942. Tens of thousands of Japanese Canadians were placed in internment camps in British Columbia; prison of war camps in Ontario; and families were also sent as forced labourers to farms throughout the prairies. By 1943, all properties owned by Japanese Canadians in British Columbia were seized and sold without consent.

Unlike Korean Americans who have relatively much longer history settling in the United States, very few settled in Canada; as late as 1965, the total permanent Korean population of Canada was estimated at only 70.[15] However, with the 1966 reform of Canadian immigration laws, South Korean immigration to Canada began to grow.[15] By 1969, there were an estimated 2000 Koreans in Canada.[16]

In the late 1990s, South Korea became the fifth-largest source of immigrants to Canada.[17] Toronto has the country's largest absolute number of Koreans, but Vancouver is experiencing the highest rate of growth in its Korean population, with a 69% increase since 1996. Montreal was the third most popular destination for Korean migrants during this period.[18] The 1990s growth in South Korean migration to Canada occurred at a time when Canadian unemployment was high and income growth was low relative to the United States.[19] One pair of researchers demonstrated that numbers of migrants were correlated with the exchange rate; the weakness of the Canadian dollar relative to the United States dollar meant that South Korean migrants bringing savings to Canada for investment would be relatively richer than those going to the United States.[20] Other factors suggested as drivers behind the growth of South Korean immigration to Canada included domestic anti-Americanism and the large presence of Canadian English teachers in local hagwon.[21]

When Hong Kong reverted to mainland Chinese rule, people emigrated and found new homes in Canada.

Demography

editEthnic and national origins

edit| Ethnic/National Origins |

2021[1][2] | 2016[4] | 2011[5] | 2006[6] | 2001[7] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Chinese | 1,715,770 | 74.96% | 1,769,1951 | 82.39% | 1,487,5801 | 81.88% | 1,346,5101 | 82.74% | 1,094,7001 | 83.33% |

| Korean | 218,140 | 9.53% | 198,210 | 9.23% | 168,890 | 9.3% | 146,545 | 9% | 101,715 | 7.74% |

| Japanese | 129,425 | 5.65% | 121,485 | 5.66% | 109,740 | 6.04% | 98,905 | 6.08% | 85,230 | 6.49% |

| Hong Kong | 81,680 | 3.57% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Taiwanese | 64,020 | 2.8% | 36,515 | 1.7% | 30,330 | 1.67% | 17,705 | 1.09% | 18,080 | 1.38% |

| Tibetan | 9,350 | 0.41% | 8,040 | 0.37% | 5,820 | 0.32% | 4,275 | 0.26% | 1,425 | 0.11% |

| Mongolian | 9,090 | 0.4% | 7,475 | 0.35% | 5,355 | 0.29% | 3,960 | 0.24% | 1,675 | 0.13% |

| Other East Asian Origins |

61,300 | 2.68% | 6,505 | 0.3% | 9,045 | 0.5% | 9,545 | 0.59% | 10,805 | 0.82% |

| Total East Asian Canadian Population[b] |

2,288,775 | 100% | 2,147,425 | 100% | 1,816,760 | 100% | 1,627,445 | 100% | 1,313,630 | 100% |

| 1Including Hong Kong Canadians. | ||||||||||

Geographical distribution

editProvinces and territories

edit| Province | 2016[4] | 2011[5] | 2006[6] | 2001[7] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Ontario | 1,008,780 | 7.62% | 855,280 | 6.76% | 767,160 | 6.38% | 614,915 | 5.45% |

| British Columbia | 679,015 | 14.89% | 586,545 | 13.56% | 539,350 | 13.24% | 457,555 | 11.83% |

| Alberta | 232,535 | 5.85% | 191,305 | 5.36% | 166,105 | 5.1% | 129,590 | 4.41% |

| Quebec | 140,235 | 1.76% | 117,580 | 1.52% | 105,245 | 1.42% | 74,015 | 1.04% |

| Manitoba | 37,825 | 3.05% | 29,000 | 2.47% | 23,200 | 2.05% | 17,550 | 1.59% |

| Saskatchewan | 22,950 | 2.14% | 17,150 | 1.7% | 12,775 | 1.34% | 10,815 | 1.12% |

| Nova Scotia | 12,570 | 1.38% | 9,045 | 1% | 6,720 | 0.74% | 4,895 | 0.55% |

| New Brunswick | 6,585 | 0.9% | 5,345 | 0.73% | 3,960 | 0.55% | 2,430 | 0.34% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2,970 | 0.58% | 2,275 | 0.45% | 1,930 | 0.39% | 1,260 | 0.25% |

| Prince Edward Island | 3,105 | 2.22% | 2,385 | 1.74% | 475 | 0.35% | 305 | 0.23% |

| Northwest Territories | 715 | 1.74% | 620 | 1.52% | 530 | 1.29% | 410 | 1.1% |

| Yukon | 825 | 2.35% | 920 | 2.76% | 650 | 2.15% | 365 | 1.28% |

| Nunavut | 150 | 0.42% | 110 | 0.35% | 95 | 0.32% | 55 | 0.21% |

| Canada | 2,148,230 | 6.23% | 1,817,590 | 5.53% | 1,628,260 | 5.21% | 1,314,225 | 4.43% |

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c Chinese: 1,715,770 persons[2]

Korean: 218,140 persons[2]

Japanese: 129,425 persons[1]

Hong Konger: 81,680 persons[1]

Taiwanese: 64,020 persons[1]

Tibetan: 9,350 persons[1]

Mongolian: 9,090 persons[1]

Other East Asian: 61,300 persons[1] - ^ a b c d e Statistic includes combined population of Chinese Canadians, Hong Kong Canadians, Japanese Canadians, Korean Canadians, Mongolian Canadians, Taiwanese Canadians, Tibetan Canadians, and Other East Asian Canadians.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2022-10-26). "Ethnic or cultural origin by gender and age: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2022-10-26). "Visible minority and population group by generation status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2022-10-26). "The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country's religious and ethnocultural diversity". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

In 2021, just over 25 million people reported being White in the census, representing close to 70% of the total Canadian population. The vast majority reported being White only, while 2.4% also reported one or more other racialized groups.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2019-06-17). "Ethnic Origin (279), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census - 25% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2019-01-23). "Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2020-05-01). "Ethnic Origin (247), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census - 20% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2013-12-23). "Ethnic Origin (232), Sex (3) and Single and Multiple Responses (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2001 Census - 20% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ^ Claiming the Land, Dan Marshall, UBC Ph.D Thesis, 2002 (unpubl.)

- ^ McGowan's War, Donald J. Hauka, New Star Books, Vancouver (2000) ISBN 1-55420-001-6

- ^ Lim, Imogene L. "Pacific Entry, Pacific Century: Chinatowns and Chinese Canadian History" (Chapter 2). In: Lee, Josephine D., Imogene L. Lim, and Yuko Matsukawa (editors). Re/collecting Early Asian America: Essays in Cultural History. Temple University Press, 2002. ISBN 1439901201, 9781439901205. Start: 15. CITED: p. 18.

- ^ Harris, Cole. The Resettlement of British Columbia: Essays on Colonialism and Geographical Change. University of British Columbia Press, Nov 1, 2011. ISBN 0774842563, 9780774842563. p. 145.

- ^ "How Canada tried to bar the "yellow peril"" (PDF). Maclean's. 1 July 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Lisa Rose Mar (2010). Brokering Belonging: Chinese in Canada's Exclusion Era, 1885-1945. Oxford University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780199780051.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2013-04-03). "Seventh census of Canada, 1931 . v. 2. Population by areas". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2023-12-30.

- ^ a b Yoon 2006, p. 17

- ^ Kim, Jung G (Spring–Summer 1982). "Korean-language press in Ontario". Polyphony: The Bulletin of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. 4 (1): 82. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2022-09-19.

- ^ Kwak 2004, p. 8

- ^ Kwak 2004, p. 3

- ^ Han & Ibbott 2005, p. 157

- ^ Han & Ibbott 2005, p. 155

- ^ Han & Ibbott 2005, p. 160

Sources

edit- Han, J. D.; Ibbott, Peter (2005), "Korean Migration to North America: Some Prices That Matter" (PDF), Canadian Studies in Population, 32 (2): 155–176, doi:10.25336/P6XS4T, retrieved September 2, 2014

- Kwak, Min-Jung (July 2004), "An Exploration of the Korean-Canadian Community in Vancouver" (PDF), Research on Immigration and Integration in the Metropolis Working Paper Series, 4 (14), archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011, retrieved July 11, 2007

- Yoon, In-Jin (2006), "Understanding the Korean Diaspora from Comparative Perspectives" (PDF), Transformation & Prospect toward Multiethnic, Multiracial & Multicultural Society: Enhancing Intercultural Communication, Asia Culture Forum, archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2007, retrieved July 11, 2007