East Nashville is an area east of downtown Nashville in Tennessee across the Cumberland River. The area is mostly residential and mixed-use areas with businesses lining the main boulevards. The main thoroughfares are Gallatin Ave (also known as Gallatin Pike or Gallatin Road along its course) and Ellington Parkway, with smaller arteries interconnecting the neighborhoods. Some of these smaller arteries include Main Street, Shelby Avenue, Porter Road, Riverside Drive, Eastland Avenue, McFerrrin Avenue, and Woodland Street in no significant order. Ellington Parkway, which parallels Gallatin Ave and Main Street, bypasses I-24 and I-65 and connects Briley Parkway and downtown Nashville and many other secondary streets along the way. The Cumberland River confines most of the area with a semicircle design on the south, southwest and east. Since East Nashville has no defined boundaries on the west and north the exact perimeter is the cause of some debate. Some would say that Ellington Parkway creates a boundary on the west and northwest, while Cahal Avenue and Porter Road create the northern boundary, in the confines of zipcode 37206. Many would also state that with I-65 and I-24 as the western border and Briley Parkway as the northern boundary, this defines an area that constitutes Greater East Nashville.[1] East Nashville is one of about 26 suburban neighborhoods in Nashville. [2]

Neighborhoods

editThe area of Smaller East Nashville in U.S. ZIP Code 37206 has many smaller neighborhoods, each with their own character and housing styles. Rediscover East is contained in area and includes the historic neighborhoods in which the Great Fire of 1916 and the tornado of 1933 devastated. It is a larger community that contains Historic Edgefield, East End, Lockeland Springs, Shelby Hills, Boscobel Hills, Rolling Acres, Eastwood, Maxwell, and Greenwood. Further east of Rediscover East lies the neighborhoods of Rosebank, Porter Heights, and Barclay Drive. These three neighborhoods are of the newest residential areas as they contain homes primarily built in the mid-century 1950s and 1960s.[3]

Greater East Nashville not only falls within 37206, but also extends further west and north to include ZIP code 37216 and 37207. This area includes Highland Heights, Cleveland Park, McFerrin Park and Inglewood. Inglewood comprises Inglewood, South Inglewood, Dalewood and Riverwood. It includes the area of Smaller East Nashville and extends to the west to reach I-65 and moves as far north as Briley Parkway.[3]

East End

editThe area consisted of farms and trading posts early in Nashville's history. East End began in 1876 as an addition or outgrowth of the fashionable Edgefield community. It was called the East Edgefield addition at the time, but became known as East End because it was situated on the eastern city limits. By the turn of the century, East End’s population was in the hundreds. Families bought or built homes on the once farmland. Each home showcased the Victorian love of craftsmanship, intricate design and numerous decorative elements. The area was attractive because of the lack of pollution and quiet atmosphere. During the early 20th century, the East End neighborhood evolved into a stable, picturesque, and conveniently located inner city neighborhood. East End is typical of inner city neighborhoods, a well-preserved neighborhood with a high degree of visual integrity.

Historic Edgefield

editThe Edgefield village became Nashville's most exclusive suburb, with streets lined of commanding Italianate, Renaissance Revival, and Queen Anne homes. Some of these homes can still be found on Russell, Fatherland and Woodland streets, but most of these homes burned in the Great Fire of 1916. Streetcar suburbs formed in the Lockeland and East End areas as farmland and country estates were sold off and subdivided. A tornado also ravaged parts of East Nashville in 1933. In the 1950s and 1960s more neighborhoods were created and in the 1970s, when “urban pioneers” moved into the area and rehabilitated neighborhoods, also called gentrification.[4]

Lockeland Springs

editLockeland was named in 1880 when the subdivision was first being developed. The name comes from the Weakley family who originally built their homestead northeast of the original Fort Nashborough, and the tract of land passed through various family descendants over the years. Jane Locke was the wife of Col. Robert Weakley. His homestead called Lockeland was built in 1790, which was 10 years after Ft. Nashborough was founded. Weakley may have constructed the brick structure with an old log house as a part of the project. The more recent portion with an entrance to the north and the tower, facing west toward Woodland Street, was added long after the property had passed out of the ownership of the Weakley family.[4]

Parks

editShelby Park

editIn the 1890s, the Nashville Railway built a casino in Shelby Park that included an amusement park. This park went bankrupt by 1903. In 1909 the city of Nashville purchased property on which the amusement park had been located. A basin was dug for a lake. The dirt was used in building roads through the park. There were plays performed here, as well as paddleboats for rent, a large Dutch windmill, and a picnic lodge called Sycamore Lodge. Today, Shelby park remains, and Shelby Bottoms is the largest green preserve in the Nashville metro area.[4]

Shelby Bottoms

editShelby Bottoms Greenway is an 810-acre linear park approximately three miles long and one-half mile wide. Shelby Park marks the southern boundary, a residential area the western edge, the Cumberland River the east side, and Cooper Creek and another residential area define the northern boundary. The landscape is mostly flat alluvial floodplain with small upland areas and is drained by several deep ravines. Approximately 75% of the area is mowed or irregularly mowed fields that had been in agricultural use before the area became a park in 1994. The wooded area includes some upland forest with native trees. Shelby Bottoms, which has a north and south entrance with parking areas and orientation signage, includes approximately eight miles of paved multiuse greenway trails and five miles of mulched trails, an observation platform, and river overlooks.[5]

Cornelia Fort Airpark

editCornelia Fort Airpark was a privately owned, public-use airport located five nautical miles (9 km) northeast of the central business district of Nashville, in Davidson County, Tennessee, United States. The 141-acre airport was located on a bend of the Cumberland River in East Nashville from 1944 until 2011.

In 2011 Nashville bought the private Cornelia Fort Airpark which was the destination of singer Patsy Cline in her 1963 fatal plane crash. The combination of Shelby Park/Shelby Bottoms/Cornelia Fort makes up more than 1,000 acres and is the fourth largest park complex in Nashville.(trailing Beaman, Bells Bend and Warner).[6][7]

East Park

editEast Park, formed after the Great Fire of 1916, once had homes built in the late 1800s of Victorian and Italianate character. After the fire consumed these homes, the city demolished what was left and created East Park. It runs from 6th Street to 8th Street and borders Woodland Street and Russell Street. It provides a green space for East End, Edgefield and McFerrin Park neighborhoods.[5]

Architect Donald W. Southgate was hired by design the bandstand in the park, but it was removed in 1956.[8]

Cumberland Park

editCumberland Park is East Nashville's newest park. It took shape along the east bank of the Cumberland River in downtown Nashville. The park sits just south of Nissan Stadium, between the Shelby Street Pedestrian Bridge and the Gateway Bridge. The area was once a high industrial and factory based river bank that was easily accessible to ships. It also includes the former Nashville Bridge Co. building immediately adjacent to the Shelby Street Pedestrian Bridge. Nashville's new riverfront development is 10 times the size of the existing Riverfront Park on the west side of the river. The park is just one stage of developing the riverfront and it cost around 17 million to create.

Other parks in East Nashville include: Kirkpatrick Park, Cleveland Park, Douglas Park, South Inglewood Park, Tom Joy Park, McFerrin Park, Oakwood Park and Eastland Park.

History

editGreat Fire of 1916

editOn the morning of Wednesday, March 22, 1916, a fire erupted in East Nashville, destroying over 500 houses and leaving over 2,500 people homeless. The fire originated at the home of Joe Jennings, who lived next to the Seagraves Planing Mill located on North First Street. Sparks from Jennings’ home set the mill ablaze and from there the fire swept from 1st Street to Dew Street, consuming any homes and businesses in its path. Fortunately, there were few injuries and only one fatality, Johnson H. Woods, who was electrocuted by a live power line.

Unusually high winds gusting from 44–51 miles per hour across wooden-shingled roofs caused the fire to spread at a rapid pace, severely impeding the Nashville fire department’s effort to control the blaze. Desperate to contain the fire, residents formed "bucket brigades" to help fight the flames, and many hastily removed furniture from their homes in an effort to save their belongings. Nashville Fire Chief Rozetta sent telegrams appealing to every city within several hundred miles asking for engines and men to help combat the flames, and Governor Tom C. Rye mobilized the companies of the Tennessee National Guard in Nashville for guard duty and assistance with the rescue work.

Buildings belonging to the Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Aged, Woodland Street Presbyterian Church, Warner Public School, and Engine Company No. 5 were burned to the ground. Tulip Street Methodist Church and St. Ann's Episcopal Church survived, thanks to church members who left their burning homes to form bucket brigades to save them. Much of East Nashville southeast of Fifth and Woodland Streets was destroyed. Total property loss was estimated at more than 1.5 million dollars.[9]

Tornado of 1933

editIt was an unusually mild late-winter day in Nashville. A warm, moist air mass covered most of the southeast. A powerful cold front lay to the northwest, and centers of low pressure sat over the Great Lakes and western Arkansas. The warming trend had begun after the 10th of March, when the temperature had failed to rise out of the 30s. As a persistent southerly wind fed air from the Gulf of Mexico several hundred miles northward the days before. The sky remained mostly cloudy on the 14th, the thermometer climbed to a remarkable 80 degrees at 3:00 p.m., which is unusually early in the year for such a warm temperature. Despite high humidity, the citizens of Nashville no doubt enjoyed their first real taste of spring that afternoon. The fast moving cold front pushed a storm through the city rather quickly, dumping 0.81 inches of rainfall in a relatively short time. But what accompanied the squall line of severe thunderstorms was the deadliest tornado in Nashville's history. By the early evening, while the air was still warm and humid, destruction began four miles west of downtown over the rim of hills, near Charlotte Pike and Fifty-first Avenue. The damage between this point and downtown was not great, but the tornado quickly intensified. It passed either directly over or very near the State Capitol, on Charlotte Avenue, shaking glass from its windows. Then the storm hit with force on the north side of the Public Square downtown, significantly damaging several buildings, and passing within 400 feet of the Weather Bureau.

The tornado thereafter crossed the Cumberland River to reach East Nashville north of the Woodland Street Bridge, and traveled eastward. The path widened from 200 to 400 yards, and damaged a row of four-story factory buildings along First Street, and a large portion of a brick wall of the building occupied by the National Casket Company, located at Second Street and Woodland. From this point, the path of destruction spread out to a width of 600 to 800 yards. For three miles, the tornado tore through a district of homes, churches, schools, and stores. Weather Bureau meteorologist Roger M. Williamson, whose home on Eastland Avenue narrowly escaped the storm's destruction, reported "for a terrifying fraction of a minute...walls, roofs, chimneys, garages and trees were crashing only a few yards away." Property damage was extensive, numbering 1,400 homes, 16 churches, 36 stores, five factories, four schools, one library, and a lodge hall. It then continued towards Donelson and Hermitage and then weakened.

Every available policeman and substitute rushed to the area, joined soon by National Guardsmen, legionnaires, Red Cross workers, Boy Scouts, and Salvation Army members. Virtually no pillaging or looting was reported, and no panic or disorder developed in the immediate aftermath. The guardsmen continued on duty throughout the damaged areas until the city was declared under control by civil officers on the morning of March 16. By then, some of the guardsmen had been on duty up to thirty-six hours. All refused compensation for their services.

The day after the storm, Wednesday, March 15, telegraph companies reported a strenuous workload of handling messages from residents to relatives and friends who lived elsewhere, as well as telegraphic inquiries from outsiders about the storm. Long distance telephone service suffered similar stresses. By Thursday morning, work crews had cleared the streets of all debris, thus re-opening them to traffic. Organized relief was making progress in restoring order, and clearing and re-building East Nashville. Coordinated by the American Red Cross, the city's relief agencies were providing shelter, clothing, and food to storm victims.[10]

Electric streetcars

editIn the early 20th century, Nashville was home to a network of electric streetcars that gave suburbanites convenient access to the thriving business center of downtown Nashville. These streetcars were owned by Percy Warner, of the famous Nashville industrialist family. Percy Warner followed the lead of his father, James C. Warner, in the New South exploitation of natural resources with his Warner Iron Corporation in the 1870s and 1880s. The younger Warner developed an interest in the new areas of electric utilities and urban mass transportation. From 1903 to 1914 he presided over the Nashville Railway and Light Company, controlling all the city’s streetcars.[4]

Tornado of 1998

editEast Nashville was hit in a two-day tornado outbreak on April 15 and April 16, 1998. On April 16, a tornado touched down in East Nashville while cutting a swath through the greater Nashville area. At least 300 homes were damaged in East Nashville; many of which lost a good part of their roofs, and a few were destroyed. Tulip Street United Methodist Church, which was well over 100 years old, also received major damage. Trees were uprooted and telephone poles were knocked down in this area.

Tornado of 2020

editA tornado touched down in far western Davidson County about half an hour past midnight local time on March 3, 2020. It reached major EF-3 strength by the time it reached East Nashville and caused significant damage. It hit the neighborhood of Five Points particularly hard, even resulting in the deaths of two pedestrians who were struck by debris.

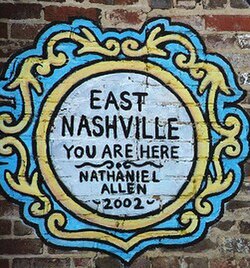

Today

editEast Nashville is an area of creative and artistic flair. It has a trendy, progressive atmosphere and after 15 or so years of rising incomes the neighborhood has managed to keep its eclectic, artsy vibe and draw a diverse mix of newcomers.[11] Its easy-going attitudes and quaint neighborhoods continue to attract young professionals and liberal-minded people. There are many coffee shops and art galleries spread about the neighborhood making it a biker's or walkers' paradise. The Tomato Art Fest is a popular summer festival in East Nashville held at Five Points, the intersection where Woodland, Clearview and 11th streets meet. Residential redevelopment that begain in the Edgefield area has spread to the outer neighborhoods and has significantly raised home prices.[11]

Cumberland Park was established along the bank of the Cumberland River in East Nashville. The park sits just south of Nissan Stadium, between the Shelby Street Pedestrian Bridge and the Gateway Bridge. The area was once, and to an extent still is, an industrial river bank that gave easy access to barges, but now parks occupy both banks of the river. The Cumberland Park project also included renovating the former Nashville Bridge Company building adjacent to the Shelby Street Pedestrian Bridge. The building houses office space, concessions and public restrooms. Nashville's new riverfront development is 10 times the size of the existing Riverfront Park on the west side of the river.[12]

On December 10, 2017, Mayor Megan Barry dedicated the first historical marker in Tennessee to honor an LGBT activist, Penny Campbell, in East Nashville.[13]

Today East Nashville has three public housing projects within it: James A. Cayce, Sam Levy Homes, and Parkway Terrace. James A. Cayce, the largest housing project in Nashville, is now being torn down and replaced by the Envision Cayce development. Sam Levy Homes, which was known as "Settle Court", has been replaced by updated public housing.

Future

editAs Nashville tries to urbanize and erase the effect of mid-century urban sprawl, East Nashville is one neighborhood that is becoming very conscious of its future. The city wants an urban environment like that of Seattle, Washington or Portland, Oregon. Nashville, along with East Nashville, is trying to set stricter building codes and design the city around pedestrians rather than cars. Along with building design and function, mass transit train system is also in the plans, which will run from the East Nashville neighborhood to midtown, just west of downtown Nashville. In "The Plan of Nashville" Gallatin Pike will be greatly affected with a complete overhaul in its function and design. In the Plan of Nashville the east bank of the Cumberland River will be greatly changed as Nissan Stadium will be surrounded by greenways and walkable streets.[14]

References

edit- ^ NashvilleBrian, "East Nashville Neighborhood Borders" 7 August 2009, "[1]", 4 January 2011

- ^ AgentSteph77, "Nashville Suburbs" "[2]",7 October 2021

- ^ a b Anita McCaig, "Neighborhoods Map" April 2010, "[3]", 20 June 2010

- ^ a b c d Ernie Gray, "The Cable Streetcars Of Early East Nashville" 4 April 2006, "[4]" 2 July 2010

- ^ a b Sandy Bivens, "Shelby Bottoms Greenway and Nature Park and Shelby Park" 19 February 2006, "[5]", 21 January 2011

- ^ "Land Trust for Tennessee | Cornelia Fort Airpark". Landtrusttn.org. 1943-03-21. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- ^ Garrison, Joey (2011-03-31). "Shelby Bottoms could expand with purchase of 132-acre airpark". Nashville City Paper. Archived from the original on 2013-07-19. Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- ^ Fleenor, E. Michael (1998). East Nashville. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 105. ISBN 9780752413396. OCLC 42081061.

- ^ Kimberly Mills, "Disasters in Tennessee" June 2000, "[6]", 18 January 2011

- ^ Mark A. Rose, "The Nashville Tornado of March 14, 1933" June 1999, "[7]", 19 January 2011

- ^ a b Rex Perry, "The South's Best Comeback Neighborhoods" 6 January 2010, "[8]", 6 July 2010

- ^ http://www.wkrn.com, "New riverfront play park named Cumberland Park" 2011, ""New riverfront play park named Cumberland Park - WKRN, Nashville, Tennessee News, Weather and Sports |". Archived from the original on 2011-08-22. Retrieved 2011-07-19.", 18 July 2011

- ^ Brant, Joseph (December 10, 2017). "Nashville LGBT pioneer Penny Campbell honored with historical marker Tennessee's first marker honoring the LGBT movement". Out & About Newspaper. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- ^ Civic Design Center, "The Plan of Nashville" 2009, ""The Plan of Nashville". Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2010-07-08.", 8 July 2010