The Knoxville campaign[1] was a series of American Civil War battles and maneuvers in East Tennessee, United States, during the fall of 1863, designed to secure control of the city of Knoxville and with it the railroad that linked the Confederacy east and west, and position the First Corps under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet for return to the Army of Northern Virginia. Union Army forces under Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside occupied Knoxville, Tennessee, and Confederate States Army forces under Longstreet were detached from Gen. Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee at Chattanooga to prevent Burnside's reinforcement of the besieged Federal forces there. Ultimately, Longstreet's Siege of Knoxville ended when Union Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman led elements of the Army of the Tennessee and other troops to Burnside's relief after Union troops had broken the Confederate siege of Chattanooga. Although Longstreet was one of Gen. Robert E. Lee's best corps commanders in the East in the Army of Northern Virginia, he was unsuccessful in his attempt to penetrate the Knoxville defenses and take the city.

| Knoxville campaign | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||

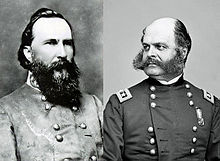

James Longstreet and Ambrose Burnside, principal commanders of the Knoxville campaign | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

|

| ||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

| Ambrose Burnside | James Longstreet | ||||

| Units involved | |||||

|

| |||||

Opposing forces

editUnion

editConfederate

editBackground and initial movements

editThe mountainous, largely Unionist region of East Tennessee was considered by President Abraham Lincoln to be a key war objective. Besides possessing a population largely loyal to the Union, the region was rich in grain and livestock and controlled the railroad corridor from Chattanooga to Virginia. Throughout 1862 and 1863, Lincoln pressured a series of commanders to move through the difficult terrain and occupy the area. Ambrose Burnside, who had been soundly defeated at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, was transferred to the Western Theater and given command of the Department and the Army of the Ohio in March 1863. Burnside was ordered to move against Knoxville as swiftly as possible while, at the same time, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans's Army of the Cumberland was ordered to operate against Bragg in Middle Tennessee (the Tullahoma campaign and the subsequent Chickamauga campaign).[2]

Burnside's plan to advance from Cincinnati, Ohio, with his two corps (IX and XXIII Corps) was delayed when the IX Corps was ordered to reinforce Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the Vicksburg campaign. While awaiting the return of the IX Corps, Burnside sent a brigade under Brig. Gen. William P. Sanders to strike at Knoxville with a combined force of cavalry and infantry. In mid-June, Sanders' Knoxville Raid destroyed railroads and disrupted communications around the city, controlled by the Confederate Department of East Tennessee, commanded by Maj. Gen. Simon B. Buckner.[3]

By mid-August, Burnside began his advance toward the city. The direct route to Knoxville ran through the Cumberland Gap, a position strongly favoring the Confederate defenders. Instead, Burnside chose to flank them. He threatened the gap from the north with the brigade commanded by Col. John F. DeCourcy, while his other two divisions swung around 40 miles (64 km) to the south of the Confederate position, over rugged mountain roads toward Knoxville. Despite poor road conditions, his men were able to march as many as 30 miles (48 km) per day.[4]

Burnside's march began on 16 August 1863 from Lexington, Kentucky and was carried out by 18,000 troops from the XXIII Corps, commanded by George Lucas Hartsuff. On their return from Vicksburg, the IX Corps troops suffered so badly from illness that they were used to garrison the line of communications. Burnside led the left-hand column through Crab Orchard, London, and Williamsburg, Kentucky to Montgomery, Tennessee. Hartsuff directed the right-hand column through Somerset, Kentucky and Chitwood, Tennessee to rendezvous at Montgomery. From there, the XXIII Corps infantry marched through Emory Gap and Winter's Gap to Kingston. The cavalry moved via Big Creek Gap farther north.[5]

As the Chickamauga campaign began, Buckner was ordered south to Chattanooga, leaving only a single brigade in the Cumberland Gap and one other east of Knoxville. Maj. Gen. Samuel Jones replaced Buckner as commander of the department at East Tennessee. One of Burnside's cavalry brigades reached Knoxville on September 2, virtually unopposed. The following day, Burnside and his main force occupied the city, welcomed warmly by the local populace.[6]

In the Cumberland Gap, 2,300 inexperienced soldiers commanded by Brig. Gen. John W. Frazer had built defenses but had no orders about what to do following Buckner's withdrawal. On September 7, confronted by DeCourcy to his north and Brig. Gen. James M. Shackelford approaching from the south, Frazer refused to surrender. Burnside and an infantry brigade commanded by Col. Samuel A. Gilbert left Knoxville and marched 60 miles (97 km) in only 52 hours. Finally realizing that he was significantly outnumbered, Frazer surrendered on September 9.[7]

Burnside dispatched some cavalry reinforcements to Rosecrans and made preparations for an expedition to clear the roads and gaps from East Tennessee to Virginia and if possible secure the saltworks beyond Abingdon. During this time, the Battle of Chickamauga loomed, and frantic requests from Washington, D.C., to move south and reinforce Rosecrans were effectively ignored by Burnside, who did not want to give up his newly occupied territory and its loyal citizens. Furthermore, Burnside was encountering difficulties in moving supplies through the rugged territory and was concerned that if he moved even farther from his supply base, he might get into serious difficulty.[8]

Battles of the East Tennessee campaign

editBlountville (September 22, 1863)

editOn September 22, Union Col. John W. Foster, with his cavalry and artillery, engaged Col. James E. Carter and his troops at Blountville. Foster attacked at noon and in the four-hour battle, shelled the town and initiated a flanking movement, compelling the Confederates to withdraw.[9]

Blue Springs (October 10)

editConfederate Brig. Gen. John S. Williams, with his cavalry force, set out to disrupt Union communications and logistics. He wished to take Bull's Gap on the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad. On October 3, while advancing on Bull's Gap, he fought with Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Carter's Union Cavalry Division, XXIII Corps, at Blue Springs, about nine miles (14 km) from Bull's Gap, on the railroad. Carter withdrew, not knowing how many of the enemy he faced. Carter and Williams skirmished for the next few days. On October 10, Carter approached Blue Springs in force. Williams had received some reinforcements. The battle began about 10:00 a.m. with Union cavalry engaging the Confederates until afternoon while another mounted force attempted to place itself in a position to cut off a Rebel retreat. Capt. Orlando M. Poe, the Chief Engineer, performed a reconnaissance to identify the best location for making an infantry attack. At 3:30 p.m., Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero's 1st Division, IX Corps, moved up to attack, which he did at 5:00 p.m. Ferrero's men broke into the Confederate line, causing heavy casualties, and advanced almost to the enemy's rear before being checked. After dark, the Confederates withdrew, and the Federals took up the pursuit in the morning. Within days, Williams and his men had retired to Virginia. Burnside had launched the East Tennessee campaign to reduce or extinguish Confederate influence in the area; Blue Springs helped fulfill that mission.[10]

Philadelphia (October 20)

editThe defeat at Blue Springs caused Jones to ask for help, which Bragg quickly provided from his Army of Tennessee. Bragg sent Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson's infantry division and the cavalry brigades of Cols. George Gibbs Dibrell and J. J. Morrison north. On October 19, Stevenson ordered the cavalry brigades to attack Col. Frank Wolford's Union cavalry brigade at Philadelphia, Tennessee. Wolford's troopers were badly beaten after being caught between Dibrell's frontal attack and Morrison's envelopment from the west. Union losses were 7 killed, 25 wounded, and 447 captured, while Confederate casualties numbered 15 killed, 82 wounded, and 70 captured. Brig. Gen. Julius White's Federal infantry and Wolford's cavalry briefly recaptured Philadelphia the following day, but Burnside soon ordered his troops to pull back to the north bank of the Tennessee River, abandoning Loudon.[11]

Longstreet advances toward Knoxville

editReacting to Burnside's victories in the Cumberland Gap and at Blue Springs, and concerned that Burnside might reinforce the Federal army that was now besieged in Chattanooga, Braxton Bragg asked Confederate President Jefferson Davis to order James Longstreet to advance against Burnside. Longstreet and parts of his First Corps of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia had arrived in northern Georgia in time to make a critical contribution to the Confederate victory at Chickamauga. Longstreet strongly objected to the order. He knew he would be significantly outnumbered, with 10,000 men in two infantry divisions (under Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws and Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins, the latter commanding the division of wounded Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood) and 5,000 cavalrymen under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, versus Burnside's 12,000 infantry and 8,500 cavalry. Furthermore, he knew that the remaining 40,000 Confederates around Chattanooga would also be outnumbered by approaching reinforcements under Grant and Sherman. Longstreet argued that, by separating the Confederate forces, "We just expose both to failure, and really take no chance to ourselves of great results."[12]

While Longstreet's men prepared for rail transport, a small skirmish occurred in Greeneville, Tennessee, on November 6. Maj. Gen. Robert Ransom Jr., and Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble" Jones dispersed Union cavalry and infantry in the area, resulting in numerous prisoners from the 7th Ohio Cavalry and the 2nd East Tennessee Mounted Infantry regiments.[13]

Longstreet's plan was to travel by railroad to Sweetwater, approximately halfway to Knoxville, but it was a journey fraught by problems. The expected trains did not arrive on time, and the men started off on foot. When the trains did arrive, they were pulled by underpowered locomotives that could not negotiate all of the mountain grades under load, forcing the men to dismount and walk alongside the cars in the steeper sections. The engineers had insufficient wood for fuel, and the men had to stop and dismantle fences along the way to continue. It took eight days for all of Longstreet's men and equipment to travel the 60 miles (97 km) to Sweetwater, and when they arrived on November 12, they found that promised supplies were not available. The men, who had traveled from the campaigns in Virginia, would not be equipped with adequate food or clothing for the winter to come.[14]

The Lincoln administration became concerned about Burnside's situation and, despite weeks of urging him to leave Knoxville and head south, now ordered him to hold the city. Grant attempted to organize a relief expedition from Chattanooga, but Burnside calmly suggested that 5,000 of his men would advance southwest toward Longstreet, establish contact, and gradually withdraw toward Knoxville, which would ensure that the Confederates could not easily return to Chattanooga and reinforce Bragg. Grant readily accepted. On November 14, Longstreet erected a bridge across the Tennessee River west of Loudon and began his pursuit of Burnside.[15]

Wheeler's cavalry approached Knoxville on November 15 and attempted to occupy the heights overlooking the city from the south bank of the Holston River, but resistance from the Federal cavalrymen under Sanders and the threat of artillery in the forts on the river's southern bank caused him to abandon his plan and rejoin Longstreet's main body on the northern side of the river.[16]

Battles of Longstreet's Knoxville campaign

editThere were several significant battles fought during Longstreet's Knoxville campaign:

Campbell's Station (November 16)

editFollowing parallel routes, Longstreet and Burnside raced for Campbell's Station, a hamlet where Concord Road, from the south, intersected Kingston Road to Knoxville. Burnside hoped to reach the crossroads first and continue on to safety in Knoxville; Longstreet planned to reach the crossroads and hold it, which would prevent Burnside from gaining Knoxville and force him to fight outside his earthworks. By forced marching on a rainy November 16, Burnside's advance reached the vital intersection and deployed first. The main column arrived at noon with the baggage train just behind. Scarcely 15 minutes later, Longstreet's Confederates approached. Longstreet attempted a double envelopment: attacks timed to strike both Union flanks simultaneously. McLaws's Confederate division struck with such force that the Union right had to redeploy, but they held. Jenkins's Confederate division maneuvered ineffectively as it advanced and was unable to turn the Union left. Burnside ordered his two divisions astride Kingston Road to withdraw three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) to a ridge in their rear. This was accomplished without confusion. The Confederates suspended their attack while Burnside continued his retrograde movement to Knoxville.[17]

The Federal withdrawal under pressure was well executed, and on November 17, the bulk of Burnside's army was within the defensive perimeter of Knoxville, and the so-called Siege of Knoxville began. The Confederates were not equipped for siege operations and were running short on supplies. On November 18, William Sanders, leading the cavalry that was screening Burnside's withdrawal, was mortally wounded in a skirmish. Longstreet planned an attack as early as November 20, but he delayed, waiting for reinforcements under Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson (3,500 men) and the cavalry brigade of Brig. Gen. Grumble Jones. Col. Edward Porter Alexander, Longstreet's artillery chief, wrote that "every day of delay added to the strength of the enemy's breastworks."[18]

Kingston (November 24)

editLongstreet worried that an isolated Union garrison at Kingston might interfere with the line of communication between his forces and Bragg's near Chattanooga. He sent Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler with two divisions of cavalry to wipe out a force that was estimated to be weak. When Wheeler's cavalrymen arrived near Kingston, they found that a brigade of Union infantry and a regiment of mounted infantry occupied a good defensive position. After an unsuccessful skirmish, the Confederate cavalry withdrew and rejoined Longstreet's command, while Wheeler himself returned to Bragg's army.[19]

Fort Sanders (November 29)

editLongstreet decided that Fort Sanders was the only vulnerable place where his men could penetrate Burnside's fortifications, which enclosed the city, and successfully conclude the siege, already a week long. The fort, named in honor of slain cavalry chief William Sanders, surmounted an eminence just northwest of Knoxville. Northwest of the fort, the land dropped off abruptly. Longstreet believed he could assemble a storming party, undetected at night, below the fortifications and overwhelm Fort Sanders by a coup de main before dawn. Following a brief artillery barrage directed at the fort's interior, three Rebel brigades charged. Union wire entanglements—telegraph wire stretched from one tree stump to another to another—delayed the attack, but the fort's outer ditch halted the Confederates. This ditch was twelve feet (3.7 m) wide and from four to ten feet (1–3 m) deep with vertical sides. The fort's exterior slope was also almost vertical. Crossing the ditch was nearly impossible, especially under withering defensive fire from musketry and canister. Confederate officers did lead their men into the ditch, but, without scaling ladders, few emerged on the scarp side, and the few who entered the fort were wounded, killed, or captured. The attack lasted twenty minutes and resulted in extremely lopsided casualties: 813 Confederate versus 13 Union.[20]

Walker's Ford (December 2)

editAbout 6,000 Union troops under Brig. Gen. Orlando B. Willcox remained near Cumberland Gap, protecting the wagon road leading back to the supply base at Camp Nelson in Kentucky.[21] Following Burnside's instructions, Willcox sent a cavalry brigade under Col. Felix W. Graham to Maynardville and began moving his infantry to Tazewell. Longstreet ordered Brig. Gen. William T. Martin to oppose Graham's thrust with three Confederate cavalry brigades. Graham pulled his brigade back toward the Clinch River and Martin's horsemen caught up with it, bringing on a clash. As Graham's cavalry were being pressed back, Willcox brought up two infantry regiments, which crossed the river at Walker's Ford, and they brought Martin's cavalry to a halt. A Confederate attempt to cross at an upstream ford was also blocked by one of Graham's regiments. Martin pulled his forces back toward Knoxville the next day.[22]

Siege lifted (December 4)

editAs Longstreet contemplated his next move, he received word that Bragg's army was soundly defeated at the Battle of Chattanooga on November 25. Although he was ordered to rejoin Bragg, Longstreet felt the order was impracticable and informed Bragg that he would return with his command to Virginia but would maintain the siege on Knoxville as long as possible in the hopes that Burnside and Grant could be prevented from joining forces and annihilating the Army of Tennessee. This plan turned out to be effective because Grant sent Sherman with 25,000 men to relieve the siege at Knoxville. Longstreet abandoned his siege on December 4 and withdrew towards Rogersville, Tennessee, 65 miles (105 km) to the northeast, preparing to go into winter quarters. Sherman left Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger at Knoxville and returned to Chattanooga with the bulk of his army. Maj. Gen. John G. Parke, Burnside's chief of staff, pursued the Confederates with a force of 8,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry, but not too closely. Longstreet continued to Rutledge on December 6 and Rogersville on December 9. Parke sent Brig. Gen. James M. Shackelford on with about 4,000 cavalry and infantry to search for Longstreet.[23]

Bean's Station (December 14)

editOn December 13, Shackelford was near Bean's Station on the Holston River. Longstreet decided to go back and capture Bean's Station. Three Confederate columns and artillery approached Bean's Station to catch the Federals in a vise. By 2:00 a.m. on December 14, one column was skirmishing with Union pickets. The pickets held out as best they could and warned Shackelford of the Confederate presence. He deployed his force for an assault. Soon, the battle started and continued throughout most of the day. Confederate flanking attacks and other assaults occurred at various times and locations, but the Federals held until Southern reinforcements arrived. By nightfall, the Federals were retiring from Bean's Station through Bean's Gap and on to Blain's Cross Roads. Longstreet set out to attack the Union forces again the next morning, but as he approached them at Blain's Cross Roads, he found them well-entrenched. Longstreet withdrew, and the Federals soon left the area.[24]

Aftermath

editThe Knoxville campaign ended following the battle of Bean's Station, and both sides went into winter quarters. The only real effect of the minor campaign was to deprive Bragg of troops he sorely needed in Chattanooga. Longstreet's foray as an independent commander was a failure, and his self-confidence was damaged. He reacted to the failure of the campaign by blaming others, as he had done at the Battle of Seven Pines in the Peninsula Campaign the previous year. He relieved Lafayette McLaws from command and requested the court martial of Brig. Gens. Jerome B. Robertson and Evander M. Law. He also submitted a letter of resignation to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper on December 30, 1863, but his request to be relieved was denied. His corps suffered through a severe winter in East Tennessee with inadequate shelter and provisions, unable to return to Virginia until the spring.[25]

Burnside's competent conduct of the campaign, despite apprehensions in Washington, partially restored his military reputation that had been damaged so severely at Fredericksburg. His successful hold on Knoxville, plus Grant's victory in Chattanooga, put much of East Tennessee under Union control for the rest of the war.[26]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ The U.S. National Park Service classifies the five battles in this article into two campaigns: the East Tennessee campaign (Blountsville and Blue Springs) and Longstreet's Knoxville campaign (Campbell's Station, Fort Sanders, Bean's Station).

- ^ Eicher, pp. 613–14; Hartley, pp. 1131–32; Korn, p. 101; Hess, ch. 1.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 613-14.

- ^ Korn, p. 101.

- ^ Cox 1882, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Korn, p. 103.

- ^ Korn, p. 104.

- ^ Korn, pp. 104-05.

- ^ NPS Blountsville

- ^ NPS Blue Springs

- ^ Hess 2013, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Eicher, p. 614; Longstreet, pp. 480–83; Alexander, p. 311; Hartley, p. 1132; Korn, p. 100.

- ^ Eicher, p. 614.

- ^ Korn, pp. 100–01; Eicher, p. 614; Hartley, p. 1132.

- ^ Hartley, pp. 1132–33; Korn, pp. 105–06; Eicher, p. 615.

- ^ Eicher, p. 614; Hartley, pp. 1132-33.

- ^ NPS Campbell's Station

- ^ Wert, p. 346; Eicher, p. 615; Korn, p. 109-11.

- ^ Hess 2013, pp. 115–118.

- ^ Eicher, p. 616; NPS Fort Sanders

- ^ Hess 2013, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Hess 2013, pp. 186–189.

- ^ Hartley, p. 1133; Eicher, pp. 616-17.

- ^ NPS Bean's Station

- ^ Wert, pp. 340–59, 360–75; Longstreet, pp. 480-523.

- ^ Hartley, p. 1133.

References

edit- Cox, Jacob D. (1882). Atlanta. Campaigns of the Civil War, IX. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Hartley, William. "Knoxville Campaign." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Hess, Earl J. (2013). The Knoxville Campaign: Burnside and Longstreet in East Tennessee. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-995-8.

- Korn, Jerry, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Fight for Chattanooga: Chickamauga to Missionary Ridge. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4816-5.

- Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial Soldier: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. ISBN 0-671-70921-6.

- National Park Service battle descriptions

Primary sources

edit- Alexander, Edward P. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander. Edited by Gary W. Gallagher. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989. ISBN 0-8078-4722-4.

- Longstreet, James. From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992. ISBN 0-306-80464-6. First published in 1896 by J. B. Lippincott and Co.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Further reading

edit- Woodworth, Steven E. Six Armies in Tennessee: The Chickamauga and Chattanooga Campaigns. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8032-9813-7.