The Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA), or Kemp–Roth Tax Cut, was an Act that introduced a major tax cut, which was designed to encourage economic growth. The Act was enacted by the 97th US Congress and signed into law by US President Ronald Reagan. The Accelerated Cost Recovery System (ACRS)[1] was a major component of the Act and was amended in 1986 to become the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS).[2]

| |

| Long title | An act to amend the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 to encourage economic growth through reduction of the tax rates for individual taxpayers, acceleration of the capital cost recovery of investment in plant, equipment, and real property, and incentives for savings, and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | ERTA |

| Nicknames | Kemp–Roth Tax Cut |

| Enacted by | the 97th United States Congress |

| Effective | August 13, 1981 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 97-34 |

| Statutes at Large | 95 Stat. 172 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

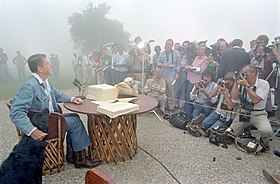

Representative Jack Kemp and Senator William Roth, both Republicans, had nearly won passage of a tax cut during the Carter presidency, but President Jimmy Carter feared an increase in the deficit and so prevented the bill's passage. Reagan made a major tax cut his top priority once he had taken office. The Democrats maintained a majority in the US House of Representatives during the 97th Congress, but Reagan convinced conservative Democrats like Phil Gramm to support the bill. The Act passed the US Congress on August 4, 1981, and it was signed into law by Reagan on August 13, 1981. It was one of the largest tax cuts in US history,[3] and ERTA and the Tax Reform Act of 1986 are known together as the Reagan tax cuts.[4] Along with spending cuts, Reagan's tax cuts were the centerpiece of what some contemporaries described as the conservative "Reagan Revolution."

Included in the act was an across-the-board decrease in the rates of federal income tax. The highest marginal tax rate fell from 70% to 50%, the lowest marginal rate from 14% to 11%. To prevent future bracket creep, the new tax rates were indexed for inflation. Also reduced were estate taxes, capital gains taxes, and corporate taxes.

Critics of the act claim that it worsened federal budget deficits, but supporters credit it for bolstering the economy during the 1980s. Supply-siders argued that the tax cuts would increase tax revenues. However, tax revenues declined relative to a baseline without the cuts because of the tax cuts, and the fiscal deficit ballooned during the Reagan presidency.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

Much of the 1981 Act was reversed in September 1982 by the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (TEFRA), which is sometimes called the largest tax increase of the postwar period.

Summary

editThe Office of Tax Analysis of the United States Department of the Treasury summarized the tax changes as follows:[12]

- phased-in 23% cut in individual tax rates over 3 years; top rate dropped from 70% to 50%

- accelerated depreciation deductions; replaced depreciation system with the Accelerated Cost Recovery System (ACRS)

- indexed individual income tax parameters (beginning in 1985)

- created 10% exclusion on income for two-earner married couples ($3,000 cap)

- phased-in increase in estate tax exemption from $175,625 to $600,000 in 1987

- reduced windfall profit taxes

- allowed all working taxpayers to establish IRAs

- expanded provisions for employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs)

- replaced $200 interest exclusion with 15% net interest exclusion ($900 cap) (begin in 1985)

The accelerated depreciation changes were repealed by the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982, and the 15% interest exclusion was repealed before it could take effect by the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984. The maximum expense in calculating credit was increased from $2000 to $2400 for one child and from $4000 to $4800 for at least two children. The credit increased from 20% or a maximum of $400 or $800 to 30% of $10,000 income or less. The 30% credit is diminished by 1% for every $2,000 of earned income up to $28,000. At $28,000, the credit for earned income was 20%.

The amount for a married taxpayer to file a joint return increased under the Economic Recovery Tax Act to $125,000 from the $100,000 allowed under the 1976 Act. A single person was limited to an exclusion of $62,500. Also increased was the one-time exclusion of gain realized on the sale of a principal residence by someone aged at least 55.[13]

Legislative history

editRepresentative Jack Kemp and Senator William Roth, both Republicans, had nearly won passage of a major tax cut during the Carter presidency, but President Jimmy Carter prevented the bill from passing out of concern about the deficit.[14] Advocates of supply-side economics like Kemp and Reagan asserted that cutting taxes would ultimately lead to higher government revenue because of economic growth, a proposition that was challenged by many economists.[15]

Upon taking office, Reagan made the passage of the bill his top domestic priority. As Democrats controlled the House of Representatives, the passage of any bill would require the support of some House Democrats in addition to that of Republicans.[16] Reagan's victory in the 1980 presidential campaign had united Republicans around his leadership, and conservative Democrats like Phil Gramm of Texas (who would later switch parties) were eager to back some of Reagan's conservative policies.[17]

Throughout 1981, Reagan frequently met with members of Congress and focused especially on winning the support from conservative Southern Democrats.[16] In July 1981, the Senate voted 89–11 for the tax cut bill favored by Reagan, and the House approved the bill in a 238–195 vote.[18] Reagan's success in passing a major tax bill and cutting the federal budget was hailed as the "Reagan Revolution" by some reporters. One columnist wrote that Reagan's legislative success represented the "most formidable domestic initiative any president has driven through since the Hundred Days of Franklin Roosevelt."[19]

Accelerated Cost Recovery System

editThe Accelerated Cost Recovery System (ACRS)[20][1] was a major component of the Act and was amended in 1986 to become the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System.

The system changed how depreciation deductions are allowed for tax purposes. The assets were placed into categories: 3, 5, 10, or 15 years of life.[21] Reducing the tax liability would put more cash into the pockets of business owners to promote investment and economic growth.[22]

For example, the agriculture industry saw a re-evaluation of their farming assets. Items such as automobiles and swine were given 3-year depreciation values, and things like buildings and land had a 15-year depreciation value.[23]

Aftermath

editThe most lasting impact and significant change of the Act was indexing the tax code parameters for inflation[20] starting in 1985. Six of the nine federal tax laws between 1968 and 1981 were tax cuts compensating for inflation-driven bracket creep.[12] Inflation was particularly high in the five years preceding the Act, and bracket creep alone caused federal individual income tax receipts to increase from 7.94% to over 10% of the GDP.[24] Even after the Act was passed, federal individual income tax receipts never fell below 8.05% of the GDP. Combined with indexing, that eliminated the need for future tax cuts to address it.[24]

The first 5% of the 25% total cuts took place beginning on October 1, 1981. An additional 10% began on July 1, 1982, followed by a third decrease of 10% starting July 1, 1983.[25]

As a result of that and other tax acts in the 1980s, the top 10% were paying 57.2% of total income taxes by 1988, up from 48% in 1981, but the bottom 50% of earners' share dropped from 7.5% to 5.7% during the same period.[25] The total share borne by middle incomes of the 50th to 95th percentiles decreased from 57.5% to the 48.7% between 1981 and 1988.[26] Much of the increase can be attributed to the decrease in capital gains taxes. Also, the ongoing recession and high unemployment contributed to stagnation among other income groups until the mid-1980s.[27]

Under ERTA, marginal tax rates dropped (top rates from 70% to 50%)and capital gains tax was reduced from 28% to 20%. Revenue from capital gains tax increased 50% from $12.5 billion in 1980 to over $18 billion in 1983.[25] In 1986, revenue from the capital gains tax rose to over $80 billion; after the restoration of the rate to 28% from 20% from 1987, capital gains revenues declined until 1991.[25]

Critics claim that the tax cuts worsened budget deficits. Reagan's supporters credit them with helping the 1980s economic expansion[28] that eventually lowered the deficits. After peaking in 1986 at $221 billion the deficit fell to $152 billion by 1989.[29] The Office of Tax Analysis estimated that the act lowered federal income tax revenue by 13% from what it would have been in the bill's absence.[30]

Canada, which had adopted the indexing of income tax in the early 1970s, saw deficits at similar and even larger levels to the United States in the late 1970s and the early 1980s.[31]

The non-partisan Congressional Research Service (in the Library of Congress) issued a report in 2012 analyzing the effects of tax rates from 1945 to 2010. It concluded that top tax rates have no positive effect on economic growth, saving, investment, or productivity growth. However, the reduced top tax rates increase income inequality:[32]

- The reduction in the top tax rates appears to be uncorrelated with saving, investment, and productivity growth. The top tax rates appear to have little or no relation to the size of the economic pie. However, the top tax rate reductions appear to be associated with the increasing concentration of income at the top of the income distribution.[33]

Tax revenue from the wealthy dropped, and much of the increased wealth collected was at the top of the tax bracket.[34][20]

Reagan came into office with a national debt of around $900 billion, high unemployment rates, and public distrust in government. The Act was designed to give tax breaks to all citizens in hopes of jumpstarting the economy and creating more wealth in the country. By the summer of 1982, the double-dip recession, the return of high-interest rates, and the ballooning deficits had convinced Congress that the Act had failed to create the results for which the Reagan administration had hoped. Largely at the initiative of Senate Finance Committee chairman Robert Dole, most of the personal tax cuts were reversed in September 1982 by the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (TEFRA) but, most significantly, not the indexing of individual income tax rates. When Reagan left office, the national debt had tripled to around $2.6 trillion.

The sociologist Monica Prasad contends that these kinds of tax cuts became popular among Republican candidates because the cuts were well received by voters and could help candidates get elected.[35]

References

edit- ^ a b Steve Lohr (February 21, 1981). "Depreciation's effect on taxes". The New York Times.

- ^ "Depreciation and Amortization tax form)" (PDF). The New York Times.

- ^ Petulla, Sam; Yellin, Tal (January 30, 2018). "The biggest tax cut in history? Not quite". CNN. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ Kessler, Glenn (April 10, 2015). "Rand Paul's claim that Reagan's tax cuts produced 'more revenue' and 'tens of millions of jobs'". Washington Post. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ "Can countries lower taxes and raise revenues?". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-06-13.

- ^ "How the GOP tax overhaul compares to the Reagan-era tax bills". PBS NewsHour. 2017-12-04. Retrieved 2020-06-13.

- ^ Chait, J. (2007). The Big Con: How Washington Got Hoodwinked and Hijacked by Crackpot Economics. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-68540-0.

- ^ "Rand Paul's claim that Reagan's tax cuts produced 'more revenue' and 'tens of millions of jobs'". The Washington Post. 2015.

A Treasury Department study on the impact of tax bills since 1940, first released in 2006 and later updated, found that the 1981 tax cut reduced revenues by $208 billion in its first four years. (These figures are rendered in constant 2012 dollars.)

- ^ "How Reagan's Tax Cuts Fared". NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- ^ Treasury Department (September 2006) [2003]. "Revenue Effects of Major Tax Bills" (PDF). United States Department of the Treasury. Working Paper 81, Table 2. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

- ^ "History lesson: Do big tax cuts pay for themselves?". The Washington Post. 2017.

- ^ a b Office of Tax Analysis (September 2006) [2003]. "Revenue Effects of Major Tax Bills" (PDF) (Revised ed.). United States Department of the Treasury. Working Paper 81, page 12. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ Briner, Merlin G. "Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981". Archived from the original on 2017-03-05.

- ^ Rossinow, p. 20

- ^ Patterson, pp. 154-155

- ^ a b Leuchtenburg, pp. 599-601

- ^ Rossinow, pp. 48–49

- ^ Rossinow, pp. 61–62

- ^ Patterson, p. 157

- ^ a b c Gregg Easterbrook (June 1982). "The Myth of Oppressive Corporate Taxes". Atlantic magazine. p. 59.

- ^ Fullerton, Don, and Yolanda Kodrzycki Henderson, "Long-Run Effects of the Accelerated Cost Recovery System," The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 67, no. 3, 1985, pp. 363–372, at [1].

- ^ [14].

- ^ Batte, Marvin T. "An Evaluation of the 1981 and 1982 Federal Income Tax Laws: Implications for Farm Size Structure," North Central Journal of Agricultural Economics, vol. 7, no. 2, 1985, pp. 9–19, at [2].

- ^ a b C. Eugene Steuerle (1992). The Tax Decade: How Taxes Came to Dominate the Public Agenda. Urban Institute Press. pp. 43-44. ISBN 978-0877665229.

- ^ a b c d Arthur Laffer (June 1, 2004). "The Laffer Curve: Past, Present, and Future". Heritage.org. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ Joint Economic Committee (1996). "Reagan Tax Cuts: Lessons for Tax Reform". house.gov. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ Congressional Budget Office (1986). "Effects of the 1981 Tax Act". Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ "The Reagan Expansion >The Reagan Expansion". Ronald Reagan Information Page. Archived from the original on October 23, 2008. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ^ FY 2011 Budget of the United States Government: Historic Tables. U.S. Government Printing Office. 2010. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-16-084797-4.

- ^ Office of Tax Analysis (September 2006) [2003]. "Revenue Effects of Major Tax Bills" (PDF). treasury.gov/offices/tax-policy/offices/ota.shtml (Revised ed.). United States Department of the Treasury. Working Paper 81, page 12. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ June M. Probyn (August 23, 1981). "What Indexing Income Taxes Produced for Canada". The New York Times. Halifax, Nova Scotia. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- ^ Rick Ungar, Non-Partisan Congressional Tax Report Debunks Core Conservative Economic Theory-GOP Suppresses Study, Forbes (Nov. 2, 2012) [3]

- ^ Hungerford, Thomas L (2012-09-14). "Taxes and the Economy: An Economic Analysis of the Top Tax Rates Since 1945" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-27.

- ^ Lawrence Lindsey (1985). "The 1982 Tax Cut: The Effect of Taxpayer Behavior on Revenue and Distribution". Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Taxation Held Under the Auspices of the National Tax Association-Tax Institute of America. 78: 111–118. JSTOR 42911671.

- ^ Prasad, Monica (2012). "The Popular Origins of Neoliberalism in the Reagan Tax Cut of 1981". Journal of Policy History. 24 (3): 351–83. doi:10.1017/S0898030612000103. S2CID 154910974.

Works cited

edit- Leuchtenburg, William E. (2015). The American President: From Teddy Roosevelt to Bill Clinton. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195176162.

- Patterson, James (2005). Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195122169.

- Rossinow, Douglas C. (2015). The Reagan Era: A History of the 1980s. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231538657.

External links

edit- Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (details) as enacted in the US Statutes at Large