The merit order is a way of ranking available sources of energy, especially electrical generation, based on ascending order of price (which may reflect the order of their short-run marginal costs of production) and sometimes pollution, together with amount of energy that will be generated. In a centralized management, the ranking is so that those with the lowest marginal costs are the first ones to be brought online to meet demand, and the plants with the highest marginal costs are the last to be brought on line. Dispatching generation in this way, known as economic dispatch, minimizes the cost of production of electricity. Sometimes generating units must be started out of merit order, due to transmission congestion, system reliability or other reasons.

In environmental dispatch, additional considerations concerning reduction of pollution further complicate the power dispatch problem. The basic constraints of the economic dispatch problem remain in place but the model is optimized to minimize pollutant emission in addition to minimizing fuel costs and total power loss.[1]

The effect of renewable energy on merit order

editThe high demand for electricity during peak demand pushes up the bidding price for electricity, and the often relatively inexpensive baseload power supply mix is supplemented by 'peaking power plants', which charge a premium for their electricity.

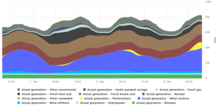

Increasing the supply of renewable energy tends to lower the average price per unit of electricity because wind energy and solar energy have very low marginal costs: they do not have to pay for fuel, and the sole contributors to their marginal cost is operations and maintenance. With cost often reduced by feed-in-tariff revenue, their electricity is as a result, less costly on the spot market than that from coal or natural gas, and transmission companies buy from them first.[2][3] Solar and wind electricity therefore substantially reduce the amount of highly priced peak electricity that transmission companies need to buy, reducing the overall cost. A study by the Fraunhofer Institute ISI found that this "merit order effect" had allowed solar power to reduce the price of electricity on the German energy exchange by 10% on average, and by as much as 40% in the early afternoon. In 2007[needs update]; as more solar electricity is fed into the grid, peak prices may come down even further.[3] By 2006, the "merit order effect" meant that the savings in electricity costs to German consumers more than offset for the support payments paid for renewable electricity generation.[3]

A 2013 study estimates the merit order effect of both wind and photovoltaic electricity generation in Germany between the years 2008 and 2012. For each additional GWh of renewables fed into the grid, the price of electricity in the day-ahead market is reduced by 0.11–0.13 ¢/kWh. The total merit order effect of wind and photovoltaics ranges from 0.5 ¢/kWh in 2010 to more than 1.1 ¢/kWh in 2012.[4]

The zero marginal cost of wind and solar energy does not, however, translate into zero marginal cost of peak load electricity in a competitive open electricity market system as wind and solar supply alone often cannot be dispatched to meet peak demand without batteries. The purpose of the merit order was to enable the lowest net cost electricity to be dispatched first thus minimising overall electricity system costs to consumers. Intermittent wind and solar is sometimes able to supply this economic function. If peak wind (or solar) supply and peak demand both coincide in time and quantity, the price reduction is larger. On the other hand, solar energy tends to be most abundant at noon, whereas peak demand is late afternoon in warm climates, leading to the so-called duck curve.

A 2008 study by the Fraunhofer Institute ISI in Karlsruhe, Germany found that windpower saves German consumers €5 billion a year. It is estimated to have lowered prices in European countries with high wind generation by between 3 and 23 €/MWh.[5][6] On the other hand, renewable energy in Germany increased the price for electricity, consumers there now pay 52.8 €/MWh more only for renewable energy (see German Renewable Energy Sources Act), average price for electricity in Germany now is increased to 26 ¢/kWh. Increasing electrical grid costs for new transmission, market trading and storage associated with wind and solar are not included in the marginal cost of power sources, instead grid costs are combined with source costs at the consumer end.

Economic dispatch

editEconomic dispatch is the short-term determination of the optimal output of a number of electricity generation facilities, to meet the system load, at the lowest possible cost, subject to transmission and operational constraints. The Economic Dispatch Problem is solved by specialized computer software which should satisfy the operational and system constraints of the available resources and corresponding transmission capabilities. In the US Energy Policy Act of 2005, the term is defined as "the operation of generation facilities to produce energy at the lowest cost to reliably serve consumers, recognising any operational limits of generation and transmission facilities".[7]

The main idea is that, in order to satisfy the load at a minimum total cost, the set of generators with the lowest marginal costs must be used first, with the marginal cost of the final generator needed to meet load setting the system marginal cost. This is the cost of delivering one additional MWh of energy onto the system. Due to transmission constraints, this cost can vary at different locations within the power grid - these different cost levels are identified as "locational marginal prices" (LMPs). The historic methodology for economic dispatch was developed to manage fossil fuel burning power plants, relying on calculations involving the input/output characteristics of power stations.

Basic mathematical formulation

editThe following is based on Biggar and Hesamzadeh (2014)[8] and Kirschen (2010).[9] The economic dispatch problem can be thought of as maximising the economic welfare W of a power network whilst meeting system constraints.

For a network with n buses (nodes), suppose that Sk is the rate of generation, and Dk is the rate of consumption at bus k. Suppose, further, that Ck(Sk) is the cost function of producing power (i.e., the rate at which the generator incurs costs when producing at rate Sk), and Vk(Dk) is the rate at which the load receives value or benefits (expressed in currency units) when consuming at rate Dk. The total welfare is then

The economic dispatch task is to find the combination of rates of production and consumption (Sk, Dk) which maximise this expression W subject to a number of constraints:

The first constraint, which is necessary to interpret the constraints that follow, is that the net injection at each bus is equal to the total production at that bus less the total consumption:

The power balance constraint requires that the sum of the net injections at all buses must be equal to the power losses in the branches of the network:

The power losses L depend on the flows in the branches and thus on the net injections as shown in the above equation. However it cannot depend on the injections on all the buses as this would give an over-determined system. Thus one bus is chosen as the Slack bus and is omitted from the variables of the function L. The choice of Slack bus is entirely arbitrary, here bus n is chosen.

The second constraint involves capacity constraints on the flow on network lines. For a system with m lines this constraint is modeled as:

where Fl is the flow on branch l, and Flmax is the maximum value that this flow is allowed to take. Note that the net injection at the slack bus is not included in this equation for the same reasons as above.

These equations can now be combined to build the Lagrangian of the optimization problem:

where π and μ are the Lagrangian multipliers of the constraints. The conditions for optimality are then:

where the last condition is needed to handle the inequality constraint on line capacity.

Solving these equations is computationally difficult as they are nonlinear and implicitly involve the solution of the power flow equations. The analysis can be simplified using a linearised model called a DC power flow.

There is a special case which is found in much of the literature. This is the case in which demand is assumed to be perfectly inelastic (i.e., unresponsive to price). This is equivalent to assuming that for some very large value of and inelastic demand . Under this assumption, the total economic welfare is maximised by choosing . The economic dispatch task reduces to:

Subject to the constraint that and the other constraints set out above.

Environmental dispatch

editIn environmental dispatch, additional considerations concerning reduction of pollution further complicate the power dispatch problem. The basic constraints of the economic dispatch problem remain in place but the model is optimized to minimize pollutant emission in addition to minimizing fuel costs and total power loss.[1] Due to the added complexity, a number of algorithms have been employed to optimize this environmental/economic dispatch problem. Notably, a modified bees algorithm implementing chaotic modeling principles was successfully applied not only in silico, but also on a physical model system of generators.[1] Other methods used to address the economic emission dispatch problem include Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)[10] and neural networks[11]

Another notable algorithm combination is used in a real-time emissions tool called Locational Emissions Estimation Methodology (LEEM) that links electric power consumption and the resulting pollutant emissions.[12] The LEEM estimates changes in emissions associated with incremental changes in power demand derived from the locational marginal price (LMP) information from the independent system operators (ISOs) and emissions data from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[12] LEEM was developed at Wayne State University as part of a project aimed at optimizing water transmission systems in Detroit, MI starting in 2010 and has since found a wider application as a load profile management tool that can help reduce generation costs and emissions.[13]

References

edit- ^ a b c Morsali, Roozbeh; Mohammadi, Mohsen; Maleksaeedi, Iman; Ghadimi, Noradin (2014). "A new multiobjective procedure for solving nonconvex environmental/economic power dispatch". Complexity. 20 (2): 47–62. Bibcode:2014Cmplx..20b..47M. doi:10.1002/cplx.21505.

- ^ William Blyth, Ming Yang, Richard A. Bradley, International Energy Agency (2007). Climate policy uncertainty and investment risk : in support of the G8 plan of action. Paris: OECD Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 9789264030145. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Frank Sensfuß; Mario Ragwitz; Massimo Genoese (2007). The Merit-order effect: A detailed analysis of the price effect of renewable electricity generation on spot market prices in Germany. Working Paper Sustainability and Innovation No. S 7/2007 (PDF). Karlsruhe: Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research (Fraunhofer ISI).

- ^ Cludius, Johanna; Hermann, Hauke; Matthes, Felix Chr. (May 2013). The merit order effect of wind and photovoltaic electricity generation in Germany 2008–2012 — CEEM Working Paper 3-2013 (PDF). Sydney, Australia: Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets (CEEM), The University of New South Wales (UNSW). Retrieved 2016-07-27.

- ^ Helm, Dieter; Powell, Andrew (1992). "Pool Prices, Contracts and Regulation in the British Electricity Supply Industry". Fiscal Studies. 13 (1): 89–105. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5890.1992.tb00501.x.

- ^ Sensfuss, Frank; Ragwitz, Mario; Massimo, Genoese (August 2008). "The merit-order effect: A detailed analysis of the price effect of renewable electricity generation on spot market prices in Germany". Energy Policy. 36 (8): 3076–3084. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.03.035. hdl:10419/28511. S2CID 13852333.

- ^ Energy Policy Act 2005.

- ^ Biggar, Darryl; Hesamzadeh, Mohammad (2014). Economics of Electricity Markets. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-77575-2.

- ^ Kirschen, Daniel (2010). Fundamentals of Power System Economics. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-84572-1.

- ^ Mason, Karl; Duggan, Jim; Howley, Enda (2017). "Multi-objective dynamic economic emission dispatch using particle swarm optimisation variants". Neurocomputing. 270: 188–197. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2017.03.086.

- ^ Mason, Karl; Duggan, Jim; Howley, Enda (2017). "Evolving multi-objective neural networks using differential evolution for dynamic economic emission dispatch". Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion. Vol. 2017. pp. 1287–1294. doi:10.1145/3067695.3082480. ISBN 9781450349390. S2CID 19492172.

- ^ a b Carter, TH; Wang, C; Miller, SS; McEllmurry, SP; Miller, CJ; Hutt, IA (2011). "Modeling of power generation pollutant emissions based on locational marginal prices for sustainable water delivery". IEEE 2011 EnergyTech. Energytech, 2011 IEEE. pp. 1, 6, 25–26. doi:10.1109/EnergyTech.2011.5948499. ISBN 978-1-4577-0777-3. S2CID 36101695.

- ^ Wang, C; McEllmurry, SP; Miller, CJ; Zhou, J (2012). "An integrated economic/Emission/Load profile management dispatch algorithm". 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting. IEEE PES General Meeting 2012. pp. 25–26. doi:10.1109/PESGM.2012.6345405. ISBN 978-1-4673-2729-9. S2CID 24866215.