Edison Park (formerly Canfield) is one of the 77 community areas of Chicago. It is located on the Northwest side of Chicago, Illinois, United States.

Edison Park | |

|---|---|

| Community Area 09 - Edison Park | |

Fieldhouse in Edison Park on the Northwest Highway | |

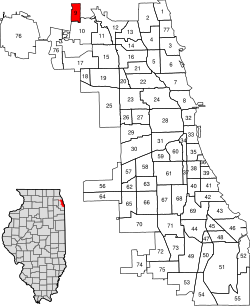

Location within the city of Chicago | |

| Coordinates: 42°0.6′N 87°48.6′W / 42.0100°N 87.8100°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Cook |

| City | Chicago |

| Neighborhoods | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.17 sq mi (3.03 km2) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 11,525 |

| • Density | 9,900/sq mi (3,800/km2) |

| Demographics 2015[1] | |

| • White | 87.32% |

| • Black | 1.07% |

| • Hispanic | 9.46% |

| • Asian | 1.46% |

| • Other | 0.70% |

| Educational Attainment 2015[1] | |

| • High School Diploma or Higher | 94.8% |

| • Bachelor's Degree or Higher | 46.3% |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | part of 60631 |

| Median household income[2] | $86,300[1] |

| Source: U.S. Census, Record Information Services | |

It consists entirely of the Edison Park neighborhood, and is named after Thomas Alva Edison,[3] who gave his blessing to this community namesake in 1890. According to the 2000 Census, its population is 11,259. Edison Park has one of the highest concentrations of Irish ancestry in Chicago, where they make up over three-fourths of the neighborhood's population.

Located between the Des Plaines River and the Chicago River, this area served as a local watershed divide. The Des Plaines River feeds into the Illinois River and the Mississippi River to reach the Gulf of Mexico. Like nearby Portage Park, Edison Park was a common portage for early travelers, who would carry their canoes across it.

History

editEdison Park's settlement history dates back to 1834 and the arrival of pioneers John and Katherine Ebinger along with their 21-year-old son Christian Ebinger and his new bride, the former Barbara Ruehle. The Ebingers had emigrated from Stuttgart, Germany, to Ann Arbor, Michigan, and then to Chicago seeking suitable farmland, but had found it too swampy.[4] As they traveled northwest from Chicago on the Indian trail to Milwaukee, Wisconsin (now Milwaukee Avenue), they crossed the North Branch of the Chicago River. However, their only horse was bitten by a snake and died, leaving them stranded. Consequently, the Ebingers decided to settle between what became Touhy and Devon Avenues. They laid claim to 80 acres around their single-story 12x14 foot cabin, and were soon joined by Christian's older brothers (Frederick and John) along with their sister Elizabeth and her husband John Plank. That area eventually became Niles Township, but as their joint families expanded, the Ebingers moved across Harlem Avenue into what became Maine Township. Barbara Ruehle Ebinger gave birth to a son, Christian Jr., in November 1834. He became the first white child born in the area, which became known as "Dutchman's Point" because of their German ancestry. The senior Christian Ebinger was a friend of local Native Americans in the area, among them Chief Blackhawk and Billy Caldwell. Christian Ebinger Jr. became the first minister to be ordained in their German Evangelical Association, and then was elected the Village Collector (1852), Village Assessor (1852-1865) and Highway Commissioner (1854-1858); he died in 1879, survived by seven children, including another Christian Ebinger.[4]

Eventually, Chicago grew and annexed part of Ebinger's homestead. Germans began moving into nearby Norwood Park (originally settled by English immigrants; but the German Evangelicals established a church as well as a Sunday School in the Ebinger home). Developers targeted the area circa 1868, Norwood Park incorporated out of Niles Township in 1874, and was annexed to Chicago in 1893.[5] It was a stop on the Chicago and Milwaukee Railroad (later the Chicago and North Western Railway line) before Park Ridge, Illinois (in Maine Township and also partly from what was once Ebinger property), and became a streetcar suburb in the 20th century.[6] Today, its oldest church building, a frame construction dating from 1894 and now known as One Hope United Methodist Church, traces its ministry's beginnings to Christian Ebinger (Methodists having united with the historic United Brethren congregation circa 1960), and a modern Ebinger descendant became a Methodist pastor near Baltimore, Maryland.[7][8]

Adjacent to the north, Edison Park (originally known as "Canfield") also developed around an intermediate railway stop between Norwood Park and Park Ridge.[9][7] It incorporated as a village in 1881[10] and developers promoted the availability of electricity; with the blessing of Thomas Alva Edison it renamed itself Edison Park in 1890.[3] Chicago annexed Edison Park on November 8, 1910.[11] A local public elementary school was named after Christian Ebinger.[12] According to the 2000 Census discussed below, Edison Park's population is 11,259.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 5,370 | — | |

| 1940 | 5,999 | 11.7% | |

| 1950 | 7,843 | 30.7% | |

| 1960 | 12,568 | 60.2% | |

| 1970 | 13,076 | 4.0% | |

| 1980 | 12,457 | −4.7% | |

| 1990 | 11,426 | −8.3% | |

| 2000 | 11,178 | −2.2% | |

| 2010 | 11,187 | 0.1% | |

| 2020 | 11,525 | 3.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[1][13] | |||

According to a 2016 analysis by the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, there were 11,208 people and 4,400 households in Edison Park. The racial makeup of the area was 87.3% White, 1.1% African American, 1.5% Asian, and 0.7% from other races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 9.5% of the population. In the area, the population was spread out, with 21.9% under the age of 19, 19.5% from 20 to 34, 23.7% from 35 to 49, 19.6% from 50 to 64, and 15.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years.[1]

The median household income was $86,300 compared to a median income of $47,831 for Chicago at-large. The area had an Income distribution in which 8.2% of households earned less than $25,000 annually; 19.7% of households earned between $25,000 and $49,999; 14.7% of households earned between $50,000 and $74,999; 16.4% of households earned between $75,000 and $99,999; 16.6% of households earned between $100,000 and $149,999 and 24.4% of households earned more than $150,000. This is compared to a distribution of 28.8%, 22.8%, 16.1%, 10.7%, 11.3% and 10.3% for Chicago at large.[1]

Arts and culture

editEdison Park Fest has been held in the area since 1972.[14]

Reaction (Chicago) released album "Edison Park" on January 15, 2015. The band explains the title was selected because Edison Park was "the neighborhood in Chicago where we used to rehearse... It's a time in our lives when possibilities seemed endless." Their album cover features Edison Park's commuter Rail station. [15]

Government

editEdison Park has narrowly voted for the Democratic Party in the past two presidential elections.[needs update] In the 2016 presidential election, Edison Park cast 2,910 votes for Hillary Clinton and cast 2,653 votes Donald Trump.[16] In the 2012 presidential election, Edison Park cast 2,736 votes for Barack Obama and cast 2,525 votes for Mitt Romney.[17]

Edison Park is entirely within the 41st ward in the Chicago City Council, where it is represented by Alderman Anthony Napolitano, who is the only Republican member of the City Council as of 2019.[18]

| Years | 27th Warda | 41st Ward | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1893 – 1894 | Mathew J. Conway, Republican | Frederick F. Haussen, Republican | No such ward |

| 1894 – 1895 | Hubert W. Butler, Republican | ||

| 1895 – 1897 | George S. Foster, Democratic | ||

| 1897 – 1899 | Spencer S. Kimbell, Republican | ||

| 1899 – 1900 | Arthur F. Keeney, Republican | ||

| 1900 – 1902 | Henry Wulff, Independent | ||

| 1902 – 1903 | Hubert W. Butler, Republican | ||

| 1903 – 1905 | Silas F. Leachman, Democratic | ||

| 1905 – 1906 | Henry J. Siewert, Republican | ||

| 1906 – 1908 | Hans Blase, Democratic | ||

| 1908 – 1909 | James F. Clancy, Republican | ||

| 1909 – 1910 | Joseph F. Capp, Republican | ||

| 1910 – 1911 | Frank J. Wilson, Democratic | ||

| 1911 – 1913 | Jens N. Hyldahl, Democratic | ||

| 1913 – 1914 | George E. Trebing, Democratic | ||

| 1914 – 1915 | Oliver L. Watson, Independent | ||

| 1915 – 1919 | John C. Kennedy, Socialist | ||

| 1919 – 1920 | Edward R. Armitage, Republican | ||

| 1920 – 1923 | Christ A. Jensen, Democratic | ||

| 1923 – 1930 | Not in ward | Thomas J. Bowler, Democratic | |

| 1930 – 1931 | Vacant | ||

| 1931 – 1935 | James C. Moreland, Republican | ||

| 1935 – 1947 | William J. Cowhey, Democratic | ||

| 1947 – 1958 | Joseph P. Immel, Jr., Republican | ||

| 1958 – 1959 | Vacant | ||

| 1959 – 1963 | Harry Bell, Democratic | ||

| 1963 – 1972 | Edward T. Scholl, Republican | ||

| 1972 – 1973 | Vacant | ||

| 1973 – 1991 | Roman Pucinski, Democratic | ||

| 1991 – 2011 | Brian Doherty, Republican | ||

| 2011 – 2015 | Mary O'Connor, Democratic | ||

| 2015 – present | Anthony Napolitano, Republican | ||

| ^a Prior to 1923 Chicago comprised 35 wards, each electing two aldermen in staggered two-year terms.[19] | |||

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editThe Union Pacific / Northwest Line has a station in the Edison Park community.

Notable people

edit- Adam Emory Albright, painter. He resided in Edison Park until moving to Warrenville, Illinois, later in life.[24]

- Leonard Crunelle, sculptor and protege of Lorado Taft.[25]

- John Mulroe, Democratic member of the Illinois Senate since 2011. He is a resident of Edison Park.[26]

- Anthony Napolitano, alderman for Chicago's 41st ward since 2015. A resident, he is also the council sole Republican.[27]

- Mary O'Connor, alderman for Chicago's 41st ward from 2011 to 2015. She is an Edison Park resident and served as president of the local chamber of commerce prior to her tenure as alderman.[27]

- Thomas A. Pope (1894–1989), recipient of the Medal of Honor for conduct at the Battle of Hamel. He was a resident of Edison Park before moving to Woodland Hills in Los Angeles.[28]

- Timothy P. Sheehan, Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from 1951 to 1959 and Republican candidate for Mayor of Chicago against Richard J. Daley in 1959.[29]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f "Community Demographic Snapshot: Edison Park" (PDF). Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. June 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Paral, Rob. "Chicago Census Data". Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ a b Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 114.

- ^ a b Dorothy Tyse, The Village of Niles, Illinois: 1899-1974 (Village of Niles, 1974), p. 7

- ^ "Norwood Park". www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org.

- ^ "221924.pdf" (PDF). Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Edison Park | History". Edison Park. Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ Guhne, Joni (12 December 1991). "PASTOR VISITS CENTURY-OLD CHURCH HIS FOREBEAR FOUNDED". baltimoresun.com.

- ^ "Edison Park". www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org.

- ^ "Monument Park | Chicago Park District". www.chicagoparkdistrict.com.

- ^ "Map of Chicago Showing Growth of the City by Annexations". chicagology.com.

- ^ "Ebinger Elementary School". ebingerschool.org.

- ^ Paral, Rob. "Chicago Community Areas Historical Data". Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ "Edison Park Fest". Edison Park Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "Edison Park, by REACTION".

- ^ Ali, Tanveer (November 9, 2016). "How Every Chicago Neighborhood Voted In The 2016 Presidential Election". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Ali, Tanveer (November 9, 2012). "How Every Chicago Neighborhood Voted In The 2012 Presidential Election". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Dukmasova, Maya (February 21, 2019). "Napolitano's challenger hopes the 41st Ward isn't as bigoted as it seems". Chicago Reader. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ a b "Centennial List of Mayors, City Clerks, City Attorneys, City Treasurers, and Aldermen, elected by the people of the city of Chicago, from the incorporation of the city on March 4, 1837 to March 4, 1937, arranged in alphabetical order, showing the years during which each official held office". Chicago Historical Society. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "A LOOK AT COOK". A Look at Cook. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ "Some Chicago GIS Data". University of Chicago Library. University of Chicago. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Germuska, Joe; Boyer, Brian. "The old and new ward maps, side-by-side -- Chicago Tribune". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Dawson, Michael. "Chicago Democracy Project - Welcome!". Chicago Democracy Project. University of Chicago. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ "Adam Emory Albright (1862 - 1957)". Museum of Wisconsin Art. June 2, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Zangs, Mary (2014). The Chicago 77: A Community Area Handbook. Charleston, SC: The History Press. pp. 190–193. ISBN 978-1-62619-612-4.

- ^ "Senator John G. Mulroe (D) - Previous General Assembly (97th) 10th District". Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ a b "Freshman Alderman Tries to Hang On to Her Seat". WTTW News.

- ^ Heise, Kenan (June 18, 1989). "WWI Medal of Honor Winner Thomas Pope". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Dyja, Thomas L. (April 8, 2013). The Third Coast: When Chicago Built the American Dream. Westminster, London, England: Penguin Books. Retrieved July 3, 2017.