Al-Burj (Arabic: البرج) was a Palestinian Arab village 14 km east of Ramle close to the highway to Ramallah, which was depopulated in 1948. Its name, "the tower", is believed to be derived from the crusader castle, Castle Arnold, built on the site. Victorian visitors in the 19th century recorded seeing crusader ruins close to the village.[6]

Al-Burj

البرج | |

|---|---|

| Etymology: The tower[1] | |

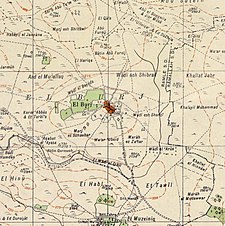

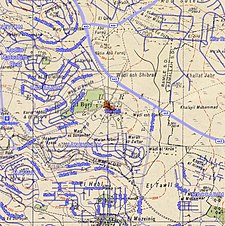

A series of historical maps of the area around Al-Burj, Ramle (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°54′07″N 35°01′14″E / 31.90194°N 35.02056°E | |

| Palestine grid | 152/145 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Ramle |

| Date of depopulation | July 15–16, 1948[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,708 dunams (4.708 km2 or 1.818 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 480[2][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Kfar Rut[5] |

Etymology

editThe name "al-Burj" is of Arabic origin, and means "The tower". The names refers to the site's Crusader keep.[7]

History

editA Byzantine lintel was found in the village in the 1870s, with "a Greek cross inscribed in a circle, and having its four arms ornamented with curious facet-work."[8]

Crusader era

editCharles Clearmont Ganneau suggested al-Burj as the site of the Castellum Arnoldi, near Beit Nuba, 'in primes auspices campestrum,' built in 1131 A.D. by the Patriarch of Jerusalem, to protect the approach to that city (William of Tyre).[9]

Just west of Al-Burj is Kŭlảt et Tantûrah, "the castle of the peak."[10] It is the remains of a tower, with 5-meter thick walls, and a door to the east. It is possible the Crusader castle called Tharenta, under Muslim rule since 1187.[11]

While nearby Bayt Jiz often has been identified as the Crusader village of Gith, some scholars (Schmitt, 1980; Fischer, Isaac and Roll, 1996) have suggested that Gith was actually at Kŭlảt et Tantûrah.[12]

Ottoman era

editIn 1838 el-Burj was noted as a Muslim village, in the Ibn Humar area in the District of Er-Ramleh.[13] It was also noted as a being small, "situated on an isolated hill surrounded by open vallies and plains." It was further noted that "there are here evident traces of an ancient site, apparently once fortified."[14]

In 1863 Victor Guérin found the village to have no more than 200 inhabitants, and noted that the Crusader fortress was in ruins.[15]

An Ottoman village list from about 1870 showed that Al-Burj had a population of 139 in a total of 31 houses, though that population count included men, only. It was further noted that it was located one hour from Beit Ur al-Tahta.[16][17]

In 1873–74 Clermont-Ganneau noted that the village was closely connected with Bir Ma'in.[8]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described Al-Burj as "a small village on a hill-top, with open ground beneath on all sides. There are remains of a Crusading fortress (Kulat et Tanturah), and the position is a strong one, near the main road to Lydda".[9]

By the beginning of the 20th century, former Bedouins from the 'Arab al-Jaramina tribe settled the in the village in and neighboring Bir Ma'in.[18]

British Mandate era

editIn the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Al Burj had a population of 344; all Muslims,[19] increasing in the 1931 census to 370, still all Muslims, in a total of 92 houses.[20]

In the 1945 statistics, the village had a population of 480 Muslims,[2] with a total land area of 4,708 dunams.[3] 6 dunams were either irrigated or used for orchards, 2,631 were used for cereals,[21] while 12 dunams were built-up (urban) areas.[22]

An elementary school for boys was completed in 1947 with around 35 pupils.[5]

1948, aftermath

editAl-Burj was occupied by the Israeli Army on July 15, 1948, during the second phase of Operation Dani. The Arab Legion counterattacked the following day with two infantry platoons and ten armoured cars but were forced to retreat. According to the Haganah 30 Arabs were killed and four armoured vehicles captured with 3 Israelis killed. Aref al-Aref records around 13 Legionaires killed.[4][5] Two elderly women and men remained. On the 23 July, one, a military cook, was sent out to pick vegetables. In his absence the other three were led to a house which, when an antitank shell missed, was blown up with six grenades. Two died: the surviving woman was then executed, and their bodies torched. The cook, on returning, didn't believe the story that they had been sent to a hospital in Ramallah, and some time later was executed with four bullets.[23] In 1992 the village site was described: "Only one crumbled house remains on the hilltop. Cactuses and wild plants grow on the site. The nearby settlements uses the village for hothouse agriculture."[24]

In 2002 a woman, Kawthar al-Amir, published a 64 page long book about Al-Burj. According to Rochelle Davis, the book is "innovatively styled for children, the descendants of the village who do not know about the village," and it is a "question and answer format, as a conversation between her and her granddaughter Bahiyya."[25]

References

edit- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 292

- ^ a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 29

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 66 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Morris, 2004, p. xix village No. 236. Also gives cause of depopulation.

- ^ a b c Khalidi, 1992, p. 371

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 371, referring to Robinson, 1841, vol 3, p. 57; and Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 15

- ^ Marom, Roy; Zadok, Ran (2023). "Early-Ottoman Palestinian Toponymy: A Linguistic Analysis of the (Micro-)Toponyms in Haseki Sultan's Endowment Deed (1552)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 139 (2).

- ^ a b Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, ARP II, p. 98

- ^ a b Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 15

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 321

- ^ Pringle, 1997, pp. 35-37

- ^ Pringle, 2009, p. 266

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 121

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, p. 57

- ^ Guérin, 1868, pp. 336-7

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 149

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 140 also noted 31 houses

- ^ Marom, Roy (2022). "Lydda Sub-District: Lydda and its countryside during the Ottoman period". Diospolis – City of God: Journal of the History, Archaeology and Heritage of Lod. 8: 124.

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Ramleh, p. 22

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 19.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 114

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 164

- ^ Adam Raz, 'Classified docs reveal massacres of Palestinians in '48 – and what Israeli leaders knew ,' Haaretz 9 December 2021

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 372

- ^ Davis, 2011, p. 34

Bibliography

edit- Al-Amir, Kawthar (2002). Likay la tansi ha dati al-Burj [So my granddaughter doesn't forget al-Burj]. Amman, Jordan: Dar ‘Alam al-Thaqafa.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1896). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873–1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. Vol. 2. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Davis, Rochelle A. (2011). Palestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the Displaced. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California. ISBN 978-0-8047-7312-6.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Pringle, D. (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521-46010-7.

- Pringle, D. (2009). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: The cities of Acre and Tyre with Addenda and Corrigenda to Volumes I-III. Vol. IV. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85148-0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links

edit- Welcome To al-Burj

- al-Burj, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- al-Burj, at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center