Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth (April 11, 1837 – May 24, 1861) was a United States Army officer and law clerk who was the first conspicuous casualty[2] and the first Union officer to die[3] in the American Civil War.[4][5] He was killed while removing a Confederate flag from the roof of the Marshall House inn in Alexandria, Virginia.[6][7]

Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth | |

|---|---|

Col. Elmer Ellsworth in 1861 | |

| Born | April 11, 1837 Malta, New York, U.S. |

| Died | May 24, 1861 (aged 24) Alexandria, Virginia, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1861 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

| Signature | |

Portrait of Elmer Ellsworth by unknown artist after Mathew Brady photograph (2011)

Coat and Pants of Colonel Ellsworth (paired images)

Before the war, Ellsworth led a touring military drill team, the "Zouave Cadets of Chicago". He was a close personal friend of Abraham Lincoln. After his death, Ellsworth's body lay in state at the White House. The phrase "Remember Ellsworth" became a rallying cry and call to arms for the Union Army.

Early life

editBorn as Ephraim Elmer Ellsworth[8] in Malta, New York, Ellsworth grew up in Mechanicville, New York, and later moved to New York City. In 1854, he moved to Rockford, Illinois, where he worked for a patent agency. In 1859, he became engaged to Carrie Spafford, the daughter of a local industrialist and city leader. When Carrie's father demanded that he find more suitable employment, he moved to Chicago to study law and work as a law clerk.

In 1860, Ellsworth moved to Springfield, Illinois, to work with Abraham Lincoln. Studying law under Lincoln, he also helped with Lincoln's 1860 campaign for president, and accompanied the new elected president to Washington, D.C. Ellsworth stood 5 ft 6 in (168 cm) tall; the six-foot-four Lincoln called him "the greatest little man I ever met".[2] After the election, Mary Todd Lincoln's youngest half-sister, Catherine "Kittie" Todd (1841–1875), visited Springfield and became infatuated with Ellsworth and they had a brief flirtation.

Career

editIn 1857, Ellsworth became drillmaster of the "Rockford Greys", the local militia company. He studied military science in his spare time. After some success with the Greys, he helped train militia units in Milwaukee and Madison. When he moved to Chicago, he became Colonel of Chicago's National Guard Cadets.

Ellsworth had studied the Zouave soldiers, French colonial troops in Algeria, and was impressed by their reported fighting quality. He outfitted his men in Zouave-style uniforms, and modeled their drill and training on the Zouaves. Ellsworth's unit became a nationally famous drill team.[9]

Following the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate Army troops in mid-April 1861, and Lincoln's subsequent call for 75,000 volunteers to defend the nation's capital, Ellsworth raised the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment (the "Fire Zouaves") from New York City's volunteer firefighting companies, and was then commissioned as the regiment's commanding officer.[10]

Death

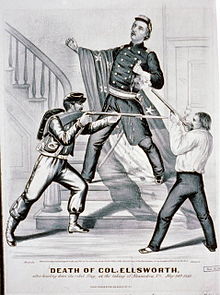

editEllsworth was killed at the Marshall House on May 24, 1861 (the day after Virginia's secession was ratified by referendum) during the Union Army's take-over of Alexandria.[6][7] During the month before the event, the inn's proprietor, James W. Jackson, had raised from the inn's roof a large Confederate flag that President Lincoln and his Cabinet had reportedly observed through field glasses from an elevated spot in Washington.[7] Jackson had reportedly stated that the flag would only be taken down "over his dead body".[4][7]

Before crossing the Potomac River to take Alexandria, soldiers serving under Ellsworth's command observed the flag from their camp through field glasses and volunteered to remove it.[11] Having seen the flag after landing in Alexandria, Ellsworth and seven other soldiers entered the inn through an open door. Once inside, they encountered a man dressed in a shirt and trousers, of whom Ellsworth demanded what sort of a flag it was that hung upon the roof.[6][11]

The man, who seemed greatly alarmed, declared he knew nothing of it, and that he was only a boarder there. Without questioning him further, Ellsworth sprang up the stairs followed by his soldiers, climbed to the roof on a ladder and cut down the flag with a soldier's knife. The soldiers turned to descend, with Private Francis E. Brownell leading the way and Ellsworth following with the flag.[6][7][11]

As Brownell reached the first landing place, Jackson jumped from a dark passage, leveled a double-barreled shotgun at Ellsworth's chest and discharged one barrel directly into Ellsworth's chest, killing him instantly. Jackson then discharged the other barrel at Brownell, but missed his target. Brownell's gun simultaneously fired, hitting Jackson in the middle of his face. Before Jackson dropped, Brownell repeatedly thrust his bayonet through Jackson's body, sending Jackson's corpse down the stairs.[6][7][11]

Ellsworth became the first Union officer to die in the Civil War.[12] Brownell, who retained a piece of the flag, was later awarded a Medal of Honor for his actions.[3][13][14]

Lincoln was deeply saddened by his friend's death and ordered an honor guard to bring his friend's body to the White House, where he lay in state in the East Room.[2][15][16] Ellsworth's body was then taken to the City Hall in New York City, where thousands of Union supporters came to see the first man to fall for the Union cause.[15] Ellsworth was then buried in his hometown of Mechanicville, in the Hudson View Cemetery (see: Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth Monument and Grave).[15]

Thousands of Union supporters rallied around Ellsworth's cause and enlisted. "Remember Ellsworth" became a patriotic slogan.[17] The 44th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment called itself the "Ellsworth Avengers" as well as "The People's Ellsworth Regiment".[18][19]

Simultaneously, Jackson became a celebrated martyr for the Confederate cause.[4][7][20] A plaque that the Sons of Confederate Veterans placed within a blind arch near a corner of a prominent hotel that stood on the former site of the Marshall House commemorated Jackson's role in the affair for many years. However, Marriott International removed the plaque in 2017 shortly after it purchased the hotel (see: Marshall House historical marker).

Legacy

editAfter the Marshall House incident, soldiers and souvenir hunters carried away pieces of the flag and inn as mementos, especially portions of the inn's stairway, balustrades, and oilcloth floor covering.[7][18][21] Relics associated with Ellsworth's death became prized souvenirs.

President Lincoln kept the captured Marshall House flag, with which his son Tad often played and waved.[4] The flag apparently passed to Brownell, and upon his death in 1894, his widow offered to sell small pieces of the flag for $10 and $15 each. She presented one fragment to "an early mentor" of her husband's; his descendants apparently sold it more than a century later.[22]

Today, most of the flag is held by the New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center in Saratoga Springs, which also has Ellsworth's uniform with an apparent bullet hole.[23] Another fragment is held by the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History, along with a blood-stained piece of oilcloth and a scrap of red bunting from the Marshall House.[24] Yet another fragment is held by Bates College's Special Collections Library.[25] A fragment bearing most of a star is on display at the Fort Ward Museum and Historic site in Alexandria, along with the kepi that Ellsworth wore when he was killed, patriotic envelopes bearing his image, and the "O" from the Marshall House sign that a soldier had taken as a souvenir.[26]

Artifacts collected during the construction of the Hotel Monaco were preserved by local archeologists. They may be seen in the Torpedo Factory Art Center's third floor exhibit (the Alexandria Archaeology Museum), three blocks away on King Street.

The new county seat of Pierce County, Wisconsin, located in the undeveloped center of the county to settle the controversy between two established cities, was named Ellsworth, Wisconsin, in his honor. He is also the namesake of Ellsworth, Michigan; DC's Fort Ellsworth, and possibly Ellsworth, Iowa; Ellsworth, Kansas; and Mount Ellsworth near Green River, Utah. A street in the Bronx, New York is named in his honor (Ellsworth Avenue).[27]

In 1936, the Greenwich Village Historical Society installed a flagpole honoring Ellsworth at the eastern end of Christopher Park at the intersection of Christopher Street and Waverly Place. It sits directly across Waverly Place from the historic Northern Dispensary building and across Christopher Street from the Stonewall Inn. The flagpole is within the boundary of the Stonewall National Monument, but the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation maintains responsibility for the flagpole. Since 2017, New York City has flown a Rainbow flag (LGBT) on the flagpole.

Song: "Brave Men, Behold Your Fallen Chief" on IMSLP by Joseph Philbrick Webster

He is a character in the 2012 film Saving Lincoln, in which his death is portrayed.

Ellsworth only recently (2021) became the topic of a full-length book by Meg Groeling entitled First Fallen: The Life of Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the North’s First Civil War Hero (Savas Beatie, 2021).

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "Ellsworth. Memorial Col. E.E. Ellsworth, the patriot martyr. The Marshall house, Alexandria, Va. Francis E. Brownell, the avenger of Ellsworth". Brady's National Photographic Portrait Galleries. Library of Congress. 1861. Retrieved February 12, 2020. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c "Elmer Ellsworth". U.S. National Park Service. June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on January 29, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- ^ a b Edwards, Owen (April 2011). "The Death of Colonel Ellsworth". Smithsonian. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Leepson, Marc (Fall 2011). Greenberg, Linda (ed.). "The First Union Civil War Martyr: Elmer Ellsworth, Alexandria, and the American Flag" (PDF). The Alexandria Chronicle. Alexandria, Virginia: Alexandria Historical Society, Inc.

- ^ Hawthorne, Frederick W. "Gettysburg: Stories of Men and Monuments", The Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides, Hanover PA 1988 p. 54 & 55

- ^ a b c d e (1) "The Murder of Colonel Ellsworth". Harper's Weekly. 5 (232): 357–358. June 8, 1861. Retrieved January 28, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

(2) "The Murder of Ellsworth". Harper's Weekly. 5 (233): 369. June 15, 1861. Retrieved January 28, 2019 – via Internet Archive. - ^ a b c d e f g h Snowden, W.H. (1894). Alexandria, Virginia. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company. pp. 5–9. LCCN rc01002851. OCLC 681385571. Retrieved January 29, 2019 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Notable Visitors: Elmer Ellsworth". Mr. Lincoln's White House. Lehrman Institute. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Giaimo, Cara (March 29, 2016). "The Civil War Fighters Who Tempted Fate With North African Fashion". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Combined Military Service Record

- ^ a b c d "Letter by Lorrequer, 1861-05-29, and statement of Brownell, Mr. F. A." 11th Infantry Regiment: New York: Civil War Newspaper Clippings: Unit History Project: New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Saratoga Springs, New York: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. March 19, 2006. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "Encounter at the Marshall House". Georgia's Blue and Gray Trail Presents America's Civil War. Georgia's Historic High Country Travel Association, the State of Georgia and Golden Ink. Archived from the original on January 1, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ "A Fragment of the Original Confederate Flag Cut Down by Col. Elmer Ellsworth at the Marshall House, and For Which He Lost His Life: Along with a note and presentation envelope for the fragment from "Ellsworth's Avenger", Frank E. Brownell, which he gave to his mentor on the way to Ellsworth's funeral". Ardmore, Pennsylvania: The Raab Collection. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ "Brownell's Medal of Honor". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on October 16, 2002. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c Goodheart, p. 288.

- ^ "Fragment of Confederate flag cut down by Colonel Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, 1861". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on April 23, 2002.

(2) Schano, N., Let's Learn from the Past: Col. Elmer Ellsworth", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 26, 2012 - ^ (1) Edwards, Owen (April 2011). "The Death of Colonel Ellsworth". Smithsonian Magazine. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

(2) "Elmer Ellsworth". U.S. National Park Service. June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on January 29, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2019. - ^ a b Goodheart, p. 289.

- ^ "44th Infantry Regiment: Civil War: Ellsworth Avengers; People's Ellsworth Regiment". New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Saratoga Springs, New York: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. January 25, 2018. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ (1) Prats, J. J. (ed.). ""Alexandria: Alexandria in the Civil War" marker". HMdb: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

(2) Fuchs, Tom (February 23, 2006). ""Alexandria: Alexandria in the Civil War" marker". HMdb: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original (photograph) on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

(3) "Wayfinding: Marshall House". City of Alexandria, Virginia. March 28, 2018. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019. - ^ (1) "Plate 1. Marshal House, Alexandria". Collections. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution: National Museum of American History. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

Relic hunters soon carried away from the hotel everything movable, including the carpets, furniture, and window shutters, and cut away the whole of the staircase and door where Ellsworth was shot.

(2) Boltz, Martha M. (May 18, 2011). "Jackson and Ellsworth: Death on both sides of the Civil War". The Washington Times. - ^ "A Fragment of the Original Confederate Flag Cut Down by Col. Elmer Ellsworth at the Marshall House, and For Which He Lost His Life: Along with a note and presentation envelope for the fragment from "Ellsworth's Avenger", Frank E. Brownell, which he gave to his mentor on the way to Ellsworth's funeral". Ardmore, Pennsylvania: The Raab Collection. 2011. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ (1) Carola, Chris (Associated Press) (June 1, 2011). "Sensational Civil War death explored in 3 places". Destination Travel. NBCNEWS.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

NEW YORK STATE MILITARY MUSEUM: .....

The museum's collection includes the uniform coat Ellsworth was wearing when Jackson fired a shotgun into his chest as the 24-year-old officer descended the stairs leading to the Marshall House's roof. The coat, still showing the hole where the slug entered, is on display, along with one of Ellsworth's swords and a Zouave drill manual.

Jackson's flag — originally 14 feet by 24 feet — is among the museum's collection of more than 800 Civil War battle flags, the largest state collection in the nation. Large swaths of the banner were cut up for souvenirs after Ellsworth's death; about 55 percent of the original flag survives. One of several large stars on Jackson's flag was removed and saved by Ellsworth's uncle, who later donated the item to a local Civil War veterans group. The neighboring Town of Saratoga came into possession of the star, which was donated to the museum in August 2006, reuniting it with the flag for the first time in more than 140 years.

(2) "About the Museum". New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Saratoga Springs, New York: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. August 2, 2016. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.The artifacts include uniforms, weapons, artillery pieces, and art. A significant portion of the museum's collection is from the Civil War. Notable artifacts from this conflict include Colonel Elmer Ellsworth's (the Union's first martyr) uniform, ... .

(3) "Marshall House Flag Confederate National Flag, First National Pattern, 1861". New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Saratoga Springs, New York: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. September 8, 2016. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

(4) "Press Release: Star Reunited After 140 Years wth [sic] Historic Elmer Ellsworth Flag". New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Saratoga Springs, New York: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. August 4, 2006. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019. - ^ (1) "Fragment of Confederate flag cut down by Colonel Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, 1861". Smithsonian Institution Press. 2001. Archived from the original on April 23, 2002.

(2) Goodheart, p. 292. - ^ "Scope and Content Note". Guide to the Benjamin F. Hayes papers, 1854, n.d.: MC096. Lewiston, Maine: Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library, Bates College. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

The journal also includes several loose pieces of paper including one paper with a red piece of cloth pinned to it. This paper has a note claiming that "This is a piece of the flag which was raised over the mansion house in Alexandria by Col. E. E. Ellsworth just before his assassination."

- ^ (1) Carola, Chris (Associated Press) (June 1, 2011). "Sensational Civil War death explored in 3 places". Destination Travel. NBCNEWS.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

FORT WARD MUSEUM AND HISTORIC SITE: .....

In addition to displays on the everyday life of Civil War soldiers, the museum features an exhibit on the "Ellsworth incident."

The exhibit includes a lock of his hair, a red kepi (cap) he wore, photographs of the young officer in uniform and contemporary published accounts of his death at the hands of James Jackson.

Most of a star from Jackson's secessionist flag, still stained with Ellsworth's blood, is on display, along with the "O" from the Marshall House sign, one of the many pieces of the structure torn off the building by souvenir-hunting Union soldiers seeking a memento from the spot where Ellsworth was slain.

(2) "Wayfinding: Marshall House". City of Alexandria, Virginia. March 28, 2018. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019. - ^ McNamara, John (1991). History in Asphalt. Harrison, NY: Harbor Hill Books. p. 95. ISBN 0-941980-15-4.

References

editGoodheart, Adam (2012). 1861: The Civil War Awakening. New York: Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc. pp. 288–289. ISBN 9781400032198. LCCN 2010051326. OCLC 973512612. Retrieved January 25, 2019 – via Google Books.

Further reading

edit- Biography of Ellsworth

- Carlson, Sarah-Eva E. (1996). "Preparing for War: Ellsworth, the Militias, and the Zouaves". Illinois History (February 1996). Springfield, Illiinois: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency: 32–34. ISSN 0019-2058. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- Davis, William C., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. First Blood: Fort Sumter to Bull Run. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books, 1983. ISBN 0-8094-4704-5.

- Ellsworth, Elmer E. (1861). Complete instructions for the recruit in the light infantry drill: as adapted to the use of the rifled musket, and arranged for the United States Zouave cadets. Cornell University Library. p. 76 pages. ISBN 1-4297-1185-X.

- Randall, Ruth Painter (1960). Colonel Elmer Ellsworth: A biography of Lincoln's friend and first hero of the Civil War. Boston: Little Brown.

External links

edit- Ellsworth's hometown and place of burial, Mechanicville, NY

- 150th Commemoration of the Civil War: The Death of Ellsworth exhibit, National Portrait Gallery, April 29, 2011 - March 18, 2012

- Smithsonian collection - shotgun used to kill Ellsworth (picture)

- Elmer Ellsworth, Citizen Soldier

- 11th Infantry Regiment: New York: Civil War Newspaper Clippings: New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center

- Envelope Cachet - Our Cause is Just. Fight on Remember Ellsworth.

- Media related to Elmer Ellsworth at Wikimedia Commons

- Texts on Wikisource: