Sarah Emma Edmonds (born Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmondson,[1] married name Seelye, alias Franklin Flint Thompson; December 1841 – September 5, 1898) was a British North America-born woman who claimed to have served as a man with the Union Army as a nurse and spy during the American Civil War. Although recognized for her service by the United States government, some historians dispute the validity of her claims as some of the details are demonstrably false, contradictory, or uncorroborated.

Sarah Emma Edmonds | |

|---|---|

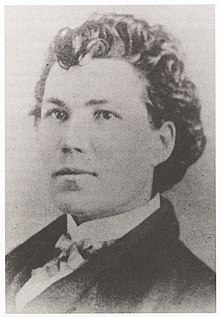

Edmonds as Franklin Thompson | |

| Nickname(s) | "Franklin Thompson" |

| Born | December 1841 Province of New Brunswick, British North America |

| Died | September 5, 1898 (age 56) La Porte, Texas |

| Buried | Glenwood Cemetery Houston, Texas |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Private, Nurse |

| Unit | |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

| Awards | In 1897, she became the second woman admitted to the Grand Army of the Republic.

In 1992, she was inducted into the Michigan Women's Hall of Fame. |

Early life

editEdmonds was born in December 1841 in New Brunswick, Canada, then a British colony. The youngest child, she grew up with her sisters and brother, Thomas, on their family's farm near Magaguadavic Lake, not far from the border with the U.S. state of Maine. She was abused by her father, who had wanted a boy to help with the crops on the farm.[2]: 18, 20–21 Thomas had "fits," which was most likely to have been epilepsy.[2]: 18 At age 15, Edmondson fled home to escape an arranged marriage; she was aided by her mother, who also had married young.[3]: 17 She changed her last name to Edmonds in order to hide from her father, and started a millinery shop with a friend in Moncton, New Brunswick. Her father eventually found her, either by himself or through acquaintances, and Edmonds fled again to escape him.[2]: 30–31

She adopted the guise of Franklin Thompson to travel more easily.[3]: 19–21 In addition, there are claims that her father had made her dress as a boy growing up, which would make her familiar and comfortable in a male role.[2]: 22–23

Thompson crossed into the United States and worked for Hurlburt and Company, a successful Bible bookseller and publisher in Hartford, Connecticut, selling Bibles door to door. Her boss, Mr. Hurlburt, claimed that she was the best salesman he had in 30 years of the business.[3]: 21

Civil War service

editEdmonds' interest in adventure was sparked in childhood by Maturin Murray Ballou's book Fanny Campbell, the Female Pirate Captain, telling the story of Fanny Campbell and her adventures on a pirate ship during the American Revolution while dressed as a man.[4][5][page needed] Campbell continued dressing as a man after the war in order to pursue other adventures. Edmonds used Campbell as an inspiration to "escape the limitations of her sex."[2]: 25 She enlisted in Company F of the 2nd Michigan Infantry on May 25, 1861, also known as the Flint Union Greys.[5][page needed] She disguised herself as a man named Franklin Flint Thompson, the middle name possibly after the city of Flint, Michigan, where she volunteered. She felt that it was her duty to serve the United States, as it was her new country.[6]: 25 She at first served as a field nurse, participating in several campaigns under General McClellan, including the First and Second Battle of Bull Run, Antietam, the Peninsula Campaign, Vicksburg, Fredericksburg, and others.

According to her memoir, Thompson's career took a turn when an American spy in Richmond, Virginia, was discovered and put before a firing squad, and her friend James Vesey was killed in an ambush. Thompson took advantage of the open position, as well as the opportunity to avenge Vesey's death, and became a spy. There is no proof in her military records that she actually served as a spy, but she wrote extensively about her experiences in her memoir.[5][page needed]

She travelled into enemy territory to gather information, requiring her to come up with many disguises. One disguise required her to use silver nitrate to dye her skin black, wear a black wig, and walk into the Confederacy disguised as a Black man by the name of Cuff. Another time, she entered the Confederacy as an Irish peddler by the name of Bridget O'Shea, claiming that she was selling apples and soap to the soldiers. Once, she was posing as a black laundress working for the Confederates when a packet of official papers fell out of an officer's jacket. She returned to the United States with the papers, and the generals were delighted. Additionally, she worked as a detective, Charles Mayberry, in Kentucky, uncovering a Confederate agent.[7][non-primary source needed]

Thompson suffered an injury before the Second Battle of Bull Run in 1862, when she took a trip to Berry's Brigade in order to deliver mail. In an attempt to take a shortcut, she was thrown into a ditch by her mule before reaching the brigade; she sustained severe injuries.[2]: 185–186, 192 In 1863, she contracted malaria. Doctors urged her to go to the hospital for treatment. Thompson abandoned her post in the army, fearing that she would be discovered as a woman if she went to a military hospital.[2]: 228–231 She checked herself into a private hospital, intending to return to military life once she had recuperated.

Once she recovered, however, she saw posters listing Frank Thompson as a deserter. Rather than return to the army under another alias or as Frank Thompson, and risk execution for desertion, she decided to serve as a female nurse under her real name at a Washington, D.C. hospital for wounded soldiers run by the United States Christian Commission.[2]: 235 There was speculation that Thompson may have deserted because of John Reid being discharged months earlier, and there is evidence in Reid's diary that she had mentioned leaving before she had contracted malaria.[2]: 231 Thompson's fellow soldiers spoke highly of her military service, and even after her disguise was discovered, they considered her a good soldier.[2]: 247 She was referred to as a fearless soldier and was active in every battle that her regiment faced.[5][6]: 29

Memoir

editIn 1864, Boston publisher DeWolfe, Fiske, & Co. published Edmonds' account of her military experiences as The Female Spy of the Union Army. One year later, her story was picked up by a Hartford, Connecticut publisher who issued it with a new title, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army. It was a huge success, selling in excess of 175,000 copies.[8] Edmonds donated the profits from her memoir to "various soldiers' aid organizations."[5][page needed]

Personal life

editIn 1867, she married Linus H. Seelye, a mechanic with whom she bore three children,[8] but all three died in their youth, leading the couple to adopt two sons.[5][page needed] Edmonds claimed that Seelye was a childhood friend; however, this was not true.[2]: 239

Later life

editIn 1882, Edmonds began the process of clearing the charge of desertion from Thompson's record in order to receive a pension. She wrote to several members of her Company, asking for them to sign affidavits on her behalf.[2]: 244–259 In 1884, Congress declared that she was owed a pension of $12 a month.[2]: 263 Thompson's charge of desertion was cleared by Congress in 1886, and she received a discharge certificate from the Adjutant General's Office in 1887.[2]: 273–274

Edmonds became a lecturer after her story received more publicity in 1883.[5][page needed]

In 1897, she became the second of only two women admitted to the Grand Army of the Republic, the Civil War Union Army veterans' organization. She was a member of the George B. McClellan Post, No. 9 in Houston, Texas.[2]: 290

Edmonds died in La Porte, Texas, on September 5, 1898, from lingering complications of malaria she had contracted in 1863.[2]: 294 She was only 56 years old. She was buried in the local cemetery, but Edmonds was laid to rest a second time in 1901 with full military honors. She is buried in the Grand Army of the Republic section of Washington Cemetery in Houston.[5][page needed]

Veracity of claims

editAs early as 1883, when asked by a newspaper reporter, "Can that book be regarded as authentic?" Edmonds responded, "Not strictly so."[2]: 249 By the 1960s, fraudulent aspects of her pension file were being discussed by historians.[9] Edmonds' biographer, Sylvia Dannett, acknowledges lies told by Edmonds in her book She Rode with the Generals.[2]: 239, 302 Edwin Fishel writes that Edmonds "almost certainly was never a spy", citing dubious claims in her memoirs as well as the absence of her name or alias among the papers of George B. McClellan, one of the Union generals in charge of Army intelligence, or in the roster of Allan Pinkerton's agents employed as spies for the Union.[10]

Dannett was also one of the few historians of the 20th century to accurately portray a woman that went into service with her biography on Edmonds.[11]: 198 DeAnne Blanton argues that "only since the early 1990s has the subject of women soldiers received renewed and serious scholarly attention."[11]: 193–204 Patricia Wilde wrote in her dissertation that many memoirs of the period, including Edmonds, Belle Boyd, and Loreta Velasquez, were purposefully using sensational rhetoric. "A kind of pathetic appeal, sensational rhetoric is the use of shocking, exciting, and thrilling language and/or subject matter for persuasive purposes."[12]: xii She argues that "disenfranchised nineteenth-century women used sensational rhetoric to circumvent obstacles that prevented them from publicly discussing issues related to the American Civil War."[12]: xii

Legacy

editA number of fictional accounts of her life were written for young adults in the 20th century, including Ann Rinaldi's Girl in Blue. Rinaldi writes of Edmonds' life and how she came to be Franklin Thompson.

American author James J. Knights presented a fictionalized account of Edmonds' wartime experiences in his book Soldier Girl Blue, published in 2019.

Edmonds was inducted into the Michigan Women's Hall of Fame in 1992.[13]

Edmonds is listed on the Canadian ACW Memorial at the Lost Villages Museum, Long Sault, Ontario. [14] [15]

Inscription: Sarah Emma Edmonds, - 2nd Michigan Infantry - Soldier, Nurse, & Spy Disguised herself as a man (Franklin Thompson) Awarded a US Army Pension. Born: Moncton, New Brunswick

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Sarah Emma Edmonds". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Dannett, Sylvia G.L. (1960). She Rode with the Generals: The True and Incredible Story of Sarah Emma Seelye, Alias Franklin Thompson. New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons. OCLC 1731436.

- ^ a b c Stevens, Bryna (1992). Frank Thompson: Her Civil War story (1st ed.). New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-788185-7. OCLC 25048778.

- ^ Ballou, Maturin Murray (1845). Fanny Campbell, the female pirate captain: a tale of the revolution. Boston: F. Gleason.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tsui, Bonnie (2003). She Went to the Field: Women Soldiers of the Civil War. Guilford, Connecticut: TwoDot. ISBN 0-7627-2438-2.

- ^ a b Eggleston, Larry G. (2003). Women in the Civil War: Extraordinary Stories of Soldiers, Spies, Nurses, Doctors, Crusaders, and Others. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1493-6.

- ^ Edmonds, S. Emma E., Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, chapter XV

- ^ a b Blanton, DeAnne (Spring 1993). "Women Soldiers of the Civil War, Part 2". Prologue Magazine: Selected Articles. Vol. 25, no. 1. OCLC 929686890.

- ^ Fladeland, Betty (1963). "New Light on Sarah Emma Edmonds, Alias Franklin Thompson". Michigan History. 47 (44): 357–362. ISSN 0026-2196.

- ^ Fishel, Edwin C. (1996). The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. Note 44, pp. 624–625. ISBN 0-395-74281-1.

- ^ a b Blanton, DeAnne; Cook, Lauren M. (2002). They Fought like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2806-6.

- ^ a b Wilde, Patricia Ann (2015). By Her Available Means: The sensational rhetoric of women's Civil War memoirs. Doctoral Dissertations. University of New Hampshire. 2195 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Sarah Emma Edmonds". Lansing, Michigan: Michigan Women's Historical Center & Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011.

- ^ "CANADIAN ACW MEMORIAL/MEMORIAL POUR LES CANADIENS DE LA GUERRE DE SESSESION". The Grays and Blues of Montreal. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ "What national monument is dedicated to the memory of those Canadians who served during the American Civil War?". memorialogy.com. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

Further reading

edit- Gansler, Laura Leedy (2007). The Mysterious Private Thompson: The Double Life of Sarah Emma Edmonds, Civil War Soldier. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-5988-1.

- Lammers, Pat; Boyce, Amy (January 1984). "A Female in the ranks: Alias Franklin Thompson". Civil War Times Illustrated. 22 (9). ISSN 0009-8094.

- Sizer, Lyde Cullen (2000). "Sara Emma Evelyn Edmonds". American National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0401184. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7.

- Wheelwright, Julie (1989). Amazons and military maids : women who dressed as men in the pursuit of life, liberty and happiness. London: Pandora. ISBN 0-04-440356-9. OCLC 1141214846.

External links

edit- Biography from Spartacus Educational which has primary sources

- University of Texas at Austin

- DeAnne Blanton - Women soldiers of the Civil War (Part 3)

- Online version of "Nurse and Spy in the Union Army"

- Online version of "Unsexed; or, The Female Soldier"

- Online version of "The female spy of the Union Army"

- Comprehensive biography

- Works by Sarah Emma Edmonds at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sarah Emma Edmonds at the Internet Archive

- Works by Sarah Emma Edmonds at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Sarah Emma Edmonds at Find a Grave

- Interview with Sarah in Ft. Scott Weekly Monitor, January 17, 1884

- Sarah in brief, current life, NY Times. March 10, 1884

- Sarah before military, Memorial Day, NY Times. May 30, 1886

- Soldier Details: Thompson, Franklin at Soldiers and Sailors Database