The Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) is a post–Cold War, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) institution. The EAPC is a multilateral forum created to improve relations between NATO and non-NATO countries in Europe and Central Asia. States meet to cooperate and discuss political and security issues. It was formed on 29 May 1997 at a Ministers’ meeting held in Sintra, Portugal, as the successor to the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC), which was created in 1991.[1]

EAPC logo | |

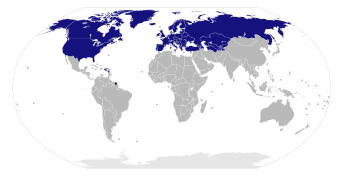

Member Suspended member | |

| Abbreviation | EAPC |

|---|---|

| Formation | 29 May 1997 |

| Headquarters | NATO Headquarters, Brussels, Belgium |

Membership | 50 countries (including Russia and Belarus who are currently suspended) |

| Website | Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council |

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: Needs more information regarding suspension of Russia and Belarus following Russian invasion of Ukraine. (August 2024) |

The EAPC provides an overall political framework for NATO’s cooperation with its partner countries in the Euro-Atlantic area. It works alongside the Partnership for Peace (PfP), which was created in January 1994. There are 50 members, including all 32 NATO member countries and 18 Partnership for Peace countries.[2] Of its members, the United States has had a notable role in the council. In the post-Cold War era, the United States served as one of the key members of the EAPC that continued to push for engagement with Russia, which is an EAPC partner country.

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia and Belarus were suspended from the Council.[3]

Background

editThe NACC and PfP

editThe EAPC serves as a successor of the NACC. The NACC, established in 1991, was created with the intention of being a forum of discussion and cooperation with NATO’s former Warsaw Pact adversaries. The NACC allowed for multilateral political consultation and cooperation, which helped build confidence in the early 1990s.[4] Additionally, the NACC paved the way for the launch of the PfP in 1994. NATO launched the PfP with the goal of forging a real partnership of peace, instead of simply engaging in the dialogue. Its role was to expand and intensify political and military cooperation throughout Europe, increase stability, diminish threats to peace, and build relationships. However, the PfP needed the assistance of another organization, such as the EAPC, to work on these tasks.[5]

By 1997, the Allies involved in the NACC recognized the desire to build a security forum that would include other Western European partners. Partners were beginning to deepen cooperation with NATO, and support for defence reform and transitions towards democracy were increasing.[6] They needed a forum that was larger and better suited for increasingly sophisticated relationships, and therefore the EAPC succeeded the NACC in 1997.

Role and structure

editIn addition to providing the overall political framework for cooperation, the EAPC provides a framework for the bilateral relationship developed between NATO and individual partner countries under the PfP program. The EAPC’s actions are based on two-year action plans. These focus on consultation and cooperation on a range of political and security related issues. [8] Under the EAPC, the ambassadors meet monthly while the foreign and defense ministers meet annually. The council's role is to maintain long-term consultation and cooperation; do crisis management and peace support operations; deal with regional issues; arms control; issues related to the proliferation of weapons and mass destruction; and international terrorism. On the defence level, the EAPC is responsible for planning, budgeting, policy and strategy, civil emergency planning, disaster preparedness, nuclear safety, air control, and scientific discovery. In addition to this, the EAPC is tasked with promoting and coordinating practical cooperation and exchange of expertise in key areas such as combatting terrorism, border security, and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and small arms. NATO and EAPC’s policies have agreed to support international efforts in regards to the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security, and combating human trafficking. [9]

Security forums

editOn May 24-25th, 2005, the EAPC held its first Security Forum in Are, Sweden. It brought together Ministers and senior decision-makers from NATO and partner countries; and representatives of civil society and think tanks. Its goal was to engage with civil society and recognize the role NGOs play in NATO’s agenda regarding peace-building and reconstruction, particularly in areas of the Balkans and Afghanistan. NATO noted that delegates had the opportunity to hold deeper discussions on Euro-Atlantic issues compared to regular ministerial meetings.[10]

In June 2007, the second Forum was held in Ohrid, Republic of Macedonia. Its focus was finding a comprehensive approach to Afghanistan, energy security, and integrating the Balkans into the Euro-Atlantic structure. The Forum included Ministers, senior officials, parliamentarians, academics, NGOs, and journalists. Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, the Secretary-General of NATO stated that they wanted participants from a range of professional backgrounds to bring about ideas, have open discussions, and understand different perspectives. [11]

Membership

editThere are 50 member countries of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council, this includes:

The 32 NATO member countries:[12]

The 18 partner countries: [13]

Four liberal democracies with capitalist economies that were militarily neutral during, and after, the Cold War:

- Austria

- Ireland

- Malta - Rejoined in 2008, it had initially joined in April 1995 and suspended its participation in October 1996.

- Switzerland

Twelve former Soviet communist republics:

Two former Yugoslav communist republics:

* Russia and Belarus are currently suspended due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Belarus being suspended because it has allowed the Russian military to use its territory to attack Ukraine.[3]

USA involvement in the EAPC

editThe USA served as one of the founding members of the NACC, the predecessor of the EAPC, in December 1991.[14] Following the collapse of the NACC and the fusion of the PfP and the EAPC, the United States continued to serve on the EAPC as one of its key members.[15]

In the post-Cold War era, The USA objective was to express more global interests in confronting crises and challenges. USA officials remained hopeful that cooperation with Russia was possible. According to Ingrid Lundestad, the inclusion of Russia within the EAPC was understood to provide reconciliation and stability to the United States and the Euro-Atlantic region.[15]

The promotion of democracy and market economics serves as an incentive for the United States to be involved in the EAPC.[15] Greater European integration in the United States, combined with a persistent transatlantic bond, is one of the greatest motivators for the United States to be involved in the EAPC.[16]

Russia and the EAPC

editIn the early 1990s, NATO Allies took several steps to engage Moscow in the Euro-Atlantic Partnership.[17] They wished to promote democratic and economic reforms in the Euro-Atlantic area, particularly with Russia following a Cold-War period.[18] Russia serves as a partner country in the EAPC. Their involvement can be traced to the first meeting of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council on December 20, 1991. The meeting took place with NATO, Eastern European nations, and the USSR present. Near the end of this meeting, the Soviet Ambassador received a message that as the meeting was taking place, the Soviet Union would cease to exist the following day. The Soviet Ambassador noted at that point that he would only be representing the Russian Federation, and no longer the Soviet Union.[19]

By 1994, Russia joined the Partnership for Peace (PfP), strengthening the ties between Russia and NATO. Upon the fusion of the PfP and NACC, Russia automatically became a member of the EAPC in 1997. The same year, the NATO-Russia Founding Act was also signed, showing cooperation following a Cold-War era. While Russia primarily rejected the notion of an alliance, rather embracing practical cooperation with NATO and its organizations such as the Euro-Atlantic Partnership, in the 1990s Russia signed and engaged with a number of partnerships with NATO, such as the NATO-Russia Partnership Commission (NRC), which, in 1997, turned into the NATO-Russia Standing Joint Commission.[17]

According to Vladimir Baranovsky, Russia’s objectives with the EAPC fall largely in the desire to promote security. Baranovsky says that Russia’s initiatives include stabilizing Europe, promoting cooperation and interaction between Europe in ‘traditional’ security-related areas and in new ideas, and narrowing differences over political and legal interpretations of Europe’s security. He also says that the most cooperative method to enhance traditional security is a three-way partnership with the United States, Russia, and NATO, and Russia is able to find this in the EAPC. Arms control in Europe is also discussed within the Council, and Russia finds an additional incentive to be a part of the EAPC due to this.[20]

Results

editAs explored in Russia and the EAPC section, the EAPC has previously served as a ‘reset’ in US-Russia relations, and by extension NATO-Russia relations.[21]

Today, the EAPC members continue to engage in partnership and dialogue. It has maintained a focus on security, stability, and democratic transformation in the Euro-Atlantic region.[22]

See also

edit- Foreign relations of NATO

- Individual Partnership Action Plan

- International organizations in Europe

- List of countries in Europe by military expenditures

- North Atlantic Council

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

- Partnership for Peace

- Russia–United States relations

- since the Russian Annexation of Crimea (2014)

- during the Trump administration (2017–2020)

- since 2021

References

edit- ^ NATO (June 22, 2021). "Euro-Atlantic Partnership".

- ^ "Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC)". The Nuclear Threat Initiative. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ a b NATO. "NATO's partnerships". NATO. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ NATO. "NATO - North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC) (Archived)". NATO. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ de Dardel, Jean-Jacques (2008). "PfP, EAPC, and the PfP Consortium: Key Elements of the Euro-Atlantic Security Community". Connections. 7 (3): 1–14. doi:10.11610/Connections.07.3.01. ISSN 1812-1098. JSTOR 26323345.

- ^ NATO. "NATO - North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC) (Archived)". NATO. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ "Openverse | WordPress.org". Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ "Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC)". The Nuclear Threat Initiative. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ NATO. "Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC)". NATO. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ "NATO Update: Security issues in focus at 46-nation forum - 24-25 May 2002". www.nato.int. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ "NATO news: Ohrid forum discusses way ahead for Afghanistan, Balkans and energy security - 28-29 June 2007". www.nato.int. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ NATO. "Member countries". NATO. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ NATO. "Euro-Atlantic Partnership". NATO. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ NATO. "NATO - North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC) (Archived)". NATO. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ a b c Lundestad, Ingrid (2016). "Turning Foe to Friend? US Objectives in Including Russia in Post-Cold War Euro-Atlantic Security Co-operation". The International History Review. 38 (4): 694–718. doi:10.1080/07075332.2015.1096806. S2CID 155652233.

- ^ Marrone, Alessandro, and Karolina, Muti (2020). "NATOʹs Future: Euro-Atlantic Alliance in a Peacetime War". Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ratti, Luca (2013). "Resetting' NATO–Russia Relations: A Realist Appraisal Two Decades after the USSR". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 26 (2): 141–161. doi:10.1080/13518046.2013.779845. S2CID 145351757.

- ^ Lundestad, Ingrid (2016). "Turning Foe to Friend? US Objectives in Including Russia in Post-Cold War Euro-Atlantic Security Co-operation". The International History Review. 38 (4): 694–718. doi:10.1080/07075332.2015.1096806. S2CID 155652233.

- ^ "Dissolution of the Soviet Union Announced at NATO Meeting". NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY ORGANIZATION. January 1, 1991.

- ^ Baranovsky, Vladimir (2010-06-01). "Russia's Approach to Security Building in the Euro–Atlantic Zone". The International Spectator. 45 (2): 41–53. doi:10.1080/03932721003790704. ISSN 0393-2729. S2CID 154780391.

- ^ Pabst, Adrian (2011). "Euro-Atlantic and Eurasian Security in a Multipolar World". American Foreign Policy Interests. 33 (1): 26–40. doi:10.1080/10803920.2011.552036. S2CID 154451120.

- ^ NATO. "Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC)". NATO. Retrieved 2022-03-18.