Everyman is a modern play produced by Charles Frohman and directed by Ben Greet that is based on the medieval morality play of the same name. The modern play was first performed in 1901 on tour in Britain. It opened in the United States in 1902 on Broadway, where it ran for 75 performances, followed by tours over the next several years that included four Broadway revivals.

| Everyman | |

|---|---|

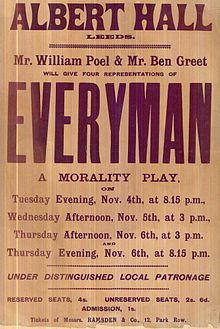

Play bill for the 1902 London production | |

| Written by | Peter Dorland |

| Date premiered | 1901 |

| Place premiered | Courtyard of the Charterhouse, London |

| Original language | English |

| Subject | Everyman looks for companions on his final journey |

| Genre | Morality play |

| Setting | Medieval Europe |

Performances

editOriginal London opening

editThe original play was written by Dutch Monk Peter van Diest (Petrus Dorlandus) about 1470 and tells the story of Everyman, who being commanded by God to begin his journey to the grave looks for companions to accompany him. Everyman then approaches a series of allegorical characters - such as Fellowship, Kindred and Knowledge - but finds that only the character representing "Good Deeds" stays with him until the end of his journey. There is no record of a modern production of this play until July 1901 when the Elizabethan Stage Society of William Poel gave three Saturday productions in an outdoor courtyard at the Charterhouse (a former monastery) in London. Poel's production was distinctive in that the actors wore costumes based on designs from Flemish tapestries.[1][2]

Broadway and West Coast productions

editEveryman attracted the notice of British actor Ben Greet, who took over most of the production and direction responsibilities, and scheduled performances throughout England, Scotland and Ireland. Greet's productions differed from past performances in that he cast women in the title role, rather than the traditional male lead. The play was so successful that plans were soon made for a North American tour to be produced by American theater manager Charles Frohman, and directed by Greet.[3] Everyman opened on Broadway with Edith Wynne Matthison in the title role on 12 October 1902 in Mendelssohn Hall, continuing on 3 November 1902 at Hoyt's Theatre, then on 17 November 1902 at the New York Theatre, and finally on 30 March 1903 at the Garden Theatre. Everyman closed its Broadway run in May 1903 after 75 performances.[4]

The first North American tour was so successful that Frohman and Greet for their second tour the next season staged both east coast and west coast productions of Everyman that also included several performances of Shakespeare tragedies and comedies. Matthison continued in the lead female roles for the east coast performances, whereas Constance Crawley, who had previously been Matthison's understudy, took the lead female roles in the west. Crawley then returned in the lead female roles in 1904 for the third North American tour, with Sybil Thorndike as her understudy. Revivals of the Broadway production took place on 4 March 1907 at the Garden Theatre with Sybil Thorndike, and on 10 January 1910 at the Garden Theatre with Thorndike once again. For the 10 March 1913 revival at the Children's Theatre (24 performances), Matthison returned to the lead role, and the final revival on 18 January 1918 at the Cort Theatre (2 performances) featured Matthison in her final performances of the role she had created on Broadway over a decade before.[4][5]

Film adaptations

editThe Everyman play was first brought to the cinema in 1913 using the Kinemacolor two-color process that projected black-and-white film through red and green filters to produce an early form of color movie.[6] Linda Arvidson, a well-known actress who was recently separated from her movie producer husband D.W. Griffith, was cast in the title role, as she at the time was the leading lady for the Kinemacolor Company of America's studios. The Natural Color Kinematograph Company in Britain was defunct in 1914 after they lost the patent for the Kinemacolor process in a lawsuit. Consequently, Kinemacolor lost its commercial value.[7] Arvidson's estranged husband bought out the California operations of Kinemacolor, which included rights to their United States film releases.[8] Griffith's acquisition of the Everyman film meant that distribution was a low priority, and despite the Broadway success of the play, the casting of a high-profile actress, and the novelty of color, the film made little impact. Subsequently, Crawley-Maude Features, which was owned by former Everyman leading lady Constance Crawley and her manager Arthur Maude, produced in 1914 their own film adaptation of Everyman, which did little better than the Kinemacolor version.[9]

See also

editNotes and references

edit- ^ Kuehler, Stephen G. (2008). Concealing God: The "Everyman" revival, 1901-1903. Tufts University (PhD. thesis). 104 p. ISBN 9780549973713.

- ^ Davidson, Clifford; Walsh, Martin W.; and Bros, Ton J., editors (2007). Everyman and its Dutch original, Elckerlijc: Introduction. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Greet, Philip Ben (1903). Everyman: being a moralle play of the XV centurie. Boston: I. Sackse. 35 p.

- ^ a b Everyman (Broadway play) at the Internet Broadway Database - 1902-1903, 1907, 1913 and 1918 productions; Everyman (Broadway play) at the Internet Broadway Database, 1910 production

- ^ Armes, William Dallam; Garnet, Porter (1903). "The morality play – its purpose and effect, and Revival of Everyman in California". Sunset Magazine: v. 11, pp. 580–583.

- ^ Everyman at IMDb - 1913 film version.

- ^ McKernan, Luke (2018). Charles Urban: Pioneering the Non-Fiction Film in Britain and America, 1897-1925. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0859892964.

- ^ "Linda Arvidson Griffith 1886-1949]" (PDF). New York Community Trust. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Everyman at IMDb - 1914 film version.

Further reading

edit- Greet, Philip Ben (1903). Everyman: being a moralle play of the XV centurie]. Boston: I. Sackse. 35 p.

- Speaight, Robert (1954), William Poel and the Elizabethan revival, London: Heinemann, pp. 161–168.