Nobody's Daughter is the fourth and final studio album by the American alternative rock band Hole, released on April 23, 2010, by Mercury Records.[2] The album was initially conceived as a solo project and follow-up to Hole frontwoman Courtney Love's first solo record, America's Sweetheart (2004).[3] At the urging of her friend and former producer Linda Perry, Love began writing material while in a lockdown rehabilitation center in 2005 following a protracted cocaine addiction and numerous related legal troubles. In 2006, Love, along with Perry and Billy Corgan, began recording the album, which at that time was tentatively titled How Dirty Girls Get Clean.

| Nobody's Daughter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | April 23, 2010 | |||

| Recorded | January 2009 – 2010 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | Alternative rock | |||

| Length | 47:09 | |||

| Label | Mercury | |||

| Producer | ||||

| Hole chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Nobody's Daughter | ||||

| ||||

Following a number of live performances of the new songs between 2006 and 2007, Love decided to scrap the project, and began writing new material with guitarist Micko Larkin, who had joined her backing band in 2007. She subsequently hired Michael Beinhorn to produce the record and began a second run of recording sessions in Los Angeles before relocating to New York City in 2009, after which Beinhorn left the project; Larkin subsequently took the role of producer. In mid-2009, it was announced that the album, retitled Nobody's Daughter, would be released as a Hole record, with guitarist Larkin, bassist Shawn Dailey, and drummer Stu Fisher as members.

Before the album's release, former Hole guitarist Eric Erlandson publicly disputed Love's use of the Hole name, claiming it violated a previous agreement between the two, which Love contested. On its release, Nobody's Daughter received generally mixed reviews from music critics, with some praising its instrumentation and lyrics, while others criticized it for its folk rock elements as well as production issues and Love's vocals. Despite this, Love said in 2010 that she considered it the best record she had made.[4]

Background

editIn September 2005, after violating a legal drug probation, Love was sentenced to a six-month program in a lock-down rehabilitation center, Beau Monde, from which she was released after one half of the sentenced time and completed the other three months under house arrest.[5] While she was in rehab, her friend and producer Linda Perry — who had previously produced her 2004 first solo album, America's Sweetheart — visited Love and supported her by encouraging her to write new songs, gifting her a Martin acoustic guitar.[6] Love then borrowed a Panasonic compact-cassette recorder and began writing material during her time in rehab.[7] "My hand-eye coordination was so bad, I didn't even know [guitar] chords anymore," Love recalled. "It was like my fingers were frozen. And I wasn't allowed to make noise [in rehab]."[8] She also told of how she would "sit there and try to quietly write and struggle", as well as of her negative mindset. "I never thought I would work again. 'No one is ever going to talk to me. I'm never going to get a record deal. I'm never going to get on stage again.' So, I just kept writing. This is a very personal album."[8]

Shortly after her release from rehab in November 2005, Love revealed the working titles of several of five of the eight tracks she composed, which included "My Bedroom Walls", "The Depths of My Despair", "Sad But True", and "How Dirty Girls Get Clean."[7] The same month, Love entered the studio and recorded a series of demos with Perry and Billy Corgan, which she dubbed The Rehab Tapes.[9] Moby, to whom Love sent several recordings, commented: "I thought the music was remarkably good, it reminded me of Irish protest songs or old Bob Dylan. It was just her with an acoustic guitar."[10] At one point, Love suggested she would be working with Moby on the album, though she subsequently chose Linda Perry as producer.[10] The album was originally conceived as Love's second solo album and followup to America's Sweetheart.[11]

Recording

edit2006–2007: Initial sessions

editIn January 2006, Love, with Perry producing and Corgan arranging, entered the Village studio in Los Angeles to begin recording the album.[12] By Love's account, the sessions lasted "66 and a half days."[13] An NME profile of the recording sessions announced the titles of several additional songs planned for the record, including "Wildfire", "Never Go Hungry Again", and an "anti-cocaine" track entitled "Loser Dust."[12] Another track, "Letter to God", written solely by Perry years before (without Love's involvement), was also recorded.[14] Perry recalled that Love had been "scrolling through my computer filled with songs and heard it and said, "I want to do this song." The lyrical content totally made sense for her. But it's not her type of song. It was more cinematic and more dramatic. It wasn't guitar-driven. It was more vulnerable, so it took me by surprise that she gravitated towards that."[14] Several guest musicians contributed to the recording sessions, including Anthony Rossomando of Dirty Pretty Things and Ben Gordon of The Dead 60s.[12] Gordon, who joined Love on guitar, recalled of the sessions: "I had an amazing time. I think she's got some really good ideas. The songs sound fresh."[12] At the time, Love cited Bob Dylan's album Blood on the Tracks as a primary influence on the record.[15]

On April 29, 2006, Love made a surprise appearance at a Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center benefit with Corgan and Perry, where she performed acoustic versions of the new songs "Sunset Marquis" and "Pacific Coast Highway".[16][17] In an interview covering the event, Love stated that the songs were "dramatically different from the demos... The songs are smashing now. I wouldn't fuck around here, this is the best shit I've done since the Live Through This period."[16] In September 2006, a documentary entitled The Return Of Courtney Love was aired on More4 in the United Kingdom and Ireland, which followed Love in her recovery as well partly documenting the recording of the album.[18] In October that year, Love performed an acoustic version of "Never Go Hungry Again" for a Rolling Stone interviewer, who observed: "this proud confessional combines simple folk-rock soundcraft with the guttural scream and lyrical fire of a never-to-be-retired riot grrrl."[19]

In early 2007, Love announced she planned to mix the album—at the time tentatively titled How Dirty Girls Get Clean—in London with Danton Supple, best known for his work with Coldplay.[20] Over the following year, she made several further live appearances showcasing the new material, including a June 2007 appearance with Perry (performing on guitar) at the Los Angeles House of Blues.[21] The following month, on July 9—Love's 43rd birthday—she performed a secret show at London's Bush Hall with a new backing band, including guitarist Micko Larkin and bassist Patricia Vidal.[22] During this time, Liam Wade also served as an additional guitarist in Love's backing band.[23] Three days later, on July 12, Love performed a free show at the Hiro Ballroom in New York City,[24] and at the Roxy Theatre in West Hollywood on July 17.[25]

2008–2009: Subsequent sessions

editIn May 2008, after several attempts at recording the album with Corgan and Perry failed to reach fruition, Love announced she was planning to scrap the record and begin reshaping it with guitarist Micko Larkin, who had joined her backing band.[26] Later that year, she hired Michael Beinhorn, with whom she had worked on Celebrity Skin (1998), to produce.[27] Under Beinhorn's supervision, a new backing band was enlisted, consisting of guitarist Larkin, bassist Shawn Dailey, and drummer Stu Fisher.[27] Recording sessions began in Glenwood Place Studios in Burbank, California in January 2009 and continued there for a number of months. Further recording was done at Henson Recording Studios in mid-2009.[28]

In late June 2009, it was reported by NME that Love intended to release the album—now titled Nobody's Daughter—as a Hole record, the name of her former band.[28] Melissa Auf der Maur, former bassist of Hole, told The Guardian at the time that Beinhorn had asked her to "sing on [Courtney's] new solo record—which is what I understood it was. And I said 'Yes' because I enjoy working with him and ... well, she and I have a history of making music together... I don't know what to say about [the situation]. I'm a little confused as to what the plan is. All I can tell you is that I like singing ooos, ahs and la-la-las behind [Courtney's] voice."[29]

"The record was taking such a toll on me. I wasn't easy for anyone to deal with because I was method acting the material. These songs were first written in rehab, at a friend's house after rehab, then at the Chateau Marmont—until I was banned from there and had to live at the Sunset Marquis. They come from a confused, lost, real place that I'm happy to no longer be in."

After instrumental tracks were recorded with Beinhorn, an "erratic" Love "slowed to a stop for several months," failing to complete vocal tracks for the album.[27] At the time, Love felt "distracted" in Los Angeles, and in late 2009 relocated to New York City to complete the record without further involvement from Beinhorn.[27] Larkin took over production duties for the remainder of the recording.[27] Reflecting on the relocation, Love said: "I can be in the real world here [in New York]. Here I can participate in life."[27] After spending several months in New York working with life coaches, therapists, and renewing her devotion to her Nichiren Buddhist practice, Love began recording the final vocal tracks for the album.[27] Bassist Dailey stated that, after relocating from Los Angeles, Love seemed like "a different person... in L.A. the record was one of many things she was doing. It was just another part of her personal life. She used to have five or six people at the studio every day waiting to have meetings with her about movie deals, about her finances. In New York she made her personal life a nonissue. She became a member of the band, just like the rest of us."[27] During this period, Love and Larkin reworked several tracks and wrote further material together.[28]

Final sessions for the album took place at Electric Lady Studios in New York City throughout late 2009.[13] According to Love, during the later recording sessions, she had been listening to Elvis Presley and various blues artists, which she cited as influential on the track "Someone Else's Bed".[30] She also cited David Bowie's album Diamond Dogs (1974), Pink Floyd's The Wall (1979), and 1980s gothic rock as influences.[13] By Love's account, she financed the making of the record herself, estimating that it ultimately cost $2 million to record and produce.[31][32]

Linda Perry, in a retrospective interview, expressed disappointment with the subsequent recording of the material: "[After we initially started recording in 2006], Courtney disappeared and came back fucked-up again. And they [Love, Beinhorn, and Larkin] re-recorded these songs badly and a beautiful record got ruined and sounded like shit. I love Courtney. She's a fabulous disaster, but she really is a genius and one of the smartest people I have ever met. I wish her well. I wish she would just do one more really serious, great record. One day I'm going to mix that [unreleased] album and fucking leak it out there. If it's ever leaked, just know that it was me who did it."[14] Perry receives producing credit on two tracks on the album: "Letter to God" and "Never Go Hungry", as well as writing credits on five of the eleven tracks.[33]

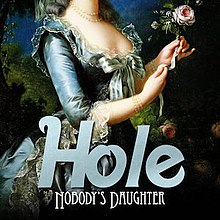

Artwork

editThe album cover is a portrait of Marie Antoinette by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, cropped at the neck, implying Antoinette's execution by guillotine.[34] This same portrait of Antoinette (in full) was also featured in the interior artwork of Hole's compilation album My Body, the Hand Grenade (1997).[35]

The back artwork of the album features a thematically similar portrait of Anne Boleyn, also cropped at the neck, while the inlay displays the 1834 painting The Execution of Lady Jane Grey by Paul Delaroche, depicting Lady Jane Grey blindfolded in the moments before her execution.[33] "The art is pretty-self evident," Love commented. "We always seem to get rid of the good dames."[36]

In the interior panel of the album liner notes, a painting titled Accident (2009) by contemporary artist Gretchen Ryan is featured, which shows a number of ballerinas walking toward the edge of a precipice; alongside it is a photo by Bennett Miller of a woman's bloodied foot in a broken glass slipper.[33]

Release and promotion

editLabel and sponsorships

editDuring the initial recording sessions with Linda Perry between 2006 and 2007, Love had intended to release the album on Perry's independent label, Custard Records.[26]

On January 5, 2009, Love claimed Nobody's Daughter had received sponsorship endorsements from several corporations, including unnamed tequila and tampon companies, totaling approximately $30 million.[32][37] In 2013, several years after the album's release, however, Love clarified: "It had over $30 million of sponsorships behind it, allegedly, and then the guy that got all the sponsorships, it turns out it was all bogus. The Red Bull, the Jordache. And he went and hung himself... He hung himself out of I guess shame."[32] In late January 2010, PRWeek announced that Love had hired the company Stoked PR to handle her public relations in the United Kingdom and Europe in an attempt to raise awareness of the upcoming release of the album, though no mention of its distributor was made.[38]

It was announced by Entertainment Weekly in February 2010 that Nobody's Daughter was scheduled for release on April 27 through Mercury Records, a subsidiary of Universal Music Group.[39] In March 2010, Universal Music Group confirmed in a press release that Love had signed with Mercury and that Nobody's Daughter, which was to be released under the Hole name, was scheduled for release on that date.[40]

On April 27, 2010, a short music video of Love getting tattooed in a tattoo parlor, overdubbed with an abridged version of the album single "Skinny Little Bitch", was released.[41] The video short was filmed by Casey Neistat.[41] A second video, featuring the band performing "Samantha" live, was released via Hole's official YouTube channel on May 4, 2010.[42]

Artist title dispute

editFollowing a June 2009 announcement that Love was releasing her upcoming album under the Hole band name,[28] former Hole guitarist Eric Erlandson commented in an interview with Spin that no reunion of the band could take place without mutual involvement between himself and Love, per a prior contract agreement; he added that there is "no Hole without me."[43]

Love publicly disputed Erlandson's claims on her Twitter account in what The Guardian described as "a deluge of often baffling tweets," writing: "Uh I just heard that a former guitar player is saying I can't use my name for MY band. He's out of his MIND. He may want to check the trademark ... and his [American Express] Disease Model Tour bills, and umm, let's see, his [1999] usage of that Amex and his [2001] usage of, wow – 298k? 198,000 DOLLARS? Hole is MY band, MY name and MY trademark."[44]

A new website promoting the band and album was subsequently published in March 2010.[45] On April 14, 2010, shortly before the release of Nobody's Daughter, Erlandson elaborated on the contract that he had mentioned in 2009, stating, "in the agreement, she agreed that she would not use the name Hole commercially without my approval. She was intent on using her name at that point, figuring it had more value than the name Hole."[46] He also claimed, "[Courtney's] management convinced me that it was all hot air and that she would never be able to finish her album. Now I'm left in an uncomfortable position" and disputed claims that he and Love reached a financial settlement over the name Hole, stating, "we haven't settled the issue. There's been no financial settlement. I'm sure what she meant to say is that she hoped for a settlement in the future. But nothing's happened yet. Courtney and her management continue to roll along with their plans to, in my opinion, ruin the Hole legacy, just for some cheap thrills."[46]

In 2014, after Love returned to performing as a solo artist, she expressed regret over releasing the album as a Hole record: "That was a mistake in 2010. Eric was right—I kind of cheapened the name, even though I'm legally allowed to use it. I should save "Hole" for the lineup everybody wants to see and had the balls to put Nobody's Daughter under my own name."[47]

Tour

editTo promote the album, Hole, with the line-up of Love, guitarist Micko Larkin, bassist Shawn Dailey, and drummer Stu Fisher, performed "Samantha" on Friday Night with Jonathan Ross on February 12, 2010. Love was also interviewed prior to the performance.[48] The band performed their first live show since their reunion at London's O2 Shepherd's Bush Empire on February 17, 2010.[49] The band performed two other European dates at Milan's Magazzini Generali, and Amsterdam's Paradiso on February 19 and 21, 2010, respectively.[50][51] "Samantha" and "Skinny Little Bitch" were performed at the NME Awards at London's O2 Academy Brixton on February 24, 2010; highlights from the show, including a shortened version of "Samantha", were broadcast on February 26, 2010, on Channel 4 in the United Kingdom and Ireland.[52]

In the United States, the band performed at Spin's annual South by Southwest music festival in Austin, Texas on March 19 and 20, 2010. These shows marked the band's first tour dates in the U.S. since their final tour in 1999.[53] For the North American leg of their tour, the band began with a show at the Fonda Theatre in Los Angeles on April 22, 2010, followed by Terminal 5 in New York City on April 27; additional U.S. and Canada tour dates were booked throughout the summer, as well as several shows in England and Scotland in early May 2010.[54] The band concluded their North American tour with a performance at Seattle's Bumbershoot festival on September 5, 2010.[55][56]

Reception

editCommercial performance

editThe album debuted at number 15 on the Billboard 200 chart, selling approximately 22,000 copies in its first week in the United States.[57] By its third week of release it had sold 33,000 copies in total.[58] According to Metromix, the album was one of the biggest commercial flops of 2010, having undersold Love's previous solo album, America's Sweetheart (also considered a commercial failure).[59]

Despite this, the album's lead single, "Skinny Little Bitch", was a commercial hit, and by April 1, 2010, had been classified a "Power Play" track by the radio conglomerate Active Rock, who gave it airplay a minimum of 50 times per week on hundreds of U.S. radio stations.[60]

Critical response

edit| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 57/100[61] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [62] |

| The Daily Telegraph | [63] |

| Entertainment Weekly | C+[64] |

| Financial Times | [65] |

| The Guardian | [66] |

| MSN Music (Consumer Guide) | A−[67] |

| NME | 6/10[68] |

| Pitchfork | 2.9/10[69] |

| Rolling Stone | [70] |

| Spin | 7/10[71] |

| The Times | [72] |

Nobody's Daughter received generally mixed reviews from music critics, holding an average score of 57 out of 100 on the review aggregator Metacritic.[73]

Petra Davis of The Quietus noted that, as with Love's previous works, Nobody's Daughter "habitually contests notions of family," as well as observing the record overall is "perceptibly the product of two distinct song cycles: one immediately post-rehab, written on the acoustic guitar Love claimed saved her life, developed and given shape by Linda Perry, Love's longtime foil and the reassuring voice behind her disastrous solo album; and another, more recent cycle, the product of more active collaboration, largely with Larkin and Billy Corgan."[74]

AllMusic writer Stephen Thomas Erlewine was critical of the record's "inward-leaning singer/songwriter roots", stating "it's impossible to disguise the turgid tuneless folk-rock swirl at the heart of Nobody's Daughter".[62] Amanda Petrusich of Pitchfork was highly critical of the album, awarding it 2.9 out of 10 rating, writing: "What are we allowed to demand from Courtney Love? More than this. Nobody's Daughter is heartbreakingly banal [and] Love's lyrics... are plastic and artless. Despite its few fleeting moments of honesty, Nobody's Daughter ultimately feels like a badly missed opportunity."[69] Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone, had a middling reception to the album, calling it "a noble effort" but not a "true success",[70] while Q Magazine said, "The main impression left by Nobody's Daughter represents no great surprise: that for all her raging intelligence, Courtney Love is only as good as her collaborators."[73]

Caroline Sullivan of The Guardian awarded the album a three out of five star rating, describing it as "alternately thrilling (see the snarling, visceral "Skinny Little Bitch") and tedious (quite a lot of the other tracks). Where Nobody's Daughter hits home is when Love thinks rather than simply reacts."[66] BBC Music alternately praised the album "rich and emotionally searing,"[75] while Billboard noted that "[with an entirely new lineup], Love sounds as self-assured as ever, sliding over syllables and hitting the emotional high notes... Nobody's Daughter recalls the highlights of the band's critically acclaimed 1994 album, Live Through This, and shows that, as a band, Hole is not one bit damaged."[76] Spin's Phoebe Reilly awarded the album seven out of ten stars, praising the album's "slick, spiraling guitars."[71]

Several critics commented on Love's diminished vocal capacity, including Tim Hermes of NPR, who wrote: "The album contains rockers like "Samantha," which ends with an unbroadcastable string of F-bombs. But Love's voice seems pretty blown out. The record's most powerful moments are ballads that show a ravaged woman who, to paraphrase an old Hole song, is lying in the bed that she's made. Often, she's addressing an absent lover."[77] Sheffield noted in his review that Love "seems to have blown her voice. In nearly every song, she croaks and gasps for breath, squeaking when she attempts to snarl. The slower the tempo, the harder she pushes to hold notes too long, as in the excruciating "For Once in Your Life" and "Someone Else's Bed.""[70] Ludovic Hunter-Tilney of the Financial Times observed that Love "sounds like Marianne Faithfull covering PJ Harvey."[65]

Aftermath

editIn 2012, Love abandoned the Hole name and returned to writing and recording as a solo artist, making Nobody's Daughter the band's final release.[78]

Track listing

edit| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Producer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Nobody's Daughter" |

| 5:19 | |

| 2. | "Skinny Little Bitch" |

|

| 3:10 |

| 3. | "Honey" |

|

| 4:19 |

| 4. | "Pacific Coast Highway" |

|

| 5:14 |

| 5. | "Samantha" |

|

| 4:16 |

| 6. | "Someone Else's Bed" |

|

| 4:26 |

| 7. | "For Once in Your Life" |

|

| 3:34 |

| 8. | "Letter to God" | Perry | Perry | 4:04 |

| 9. | "Loser Dust" |

|

| 3:25 |

| 10. | "How Dirty Girls Get Clean" |

|

| 4:54 |

| 11. | "Never Go Hungry" | Love | Perry | 4:28 |

| Total length: | 47:09 | |||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Producer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12. | "Happy Ending Story" |

|

| 3:54 |

| 13. | "Codine" (2010 version; Japanese release only) | Buffy Sainte-Marie | Larkin | 3:57 |

Personnel

edit

Guest musicians[81]

Design

Notes ^ I denotes engineer at Henson Recording Studios

|

Production[81]

|

Charts

edit| Chart (2010) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (ARIA)[83] | 50 |

| Austrian Albums (Ö3 Austria)[84] | 45 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Wallonia)[85] | 95 |

| Canadian Albums (Billboard)[86] | 11 |

| French Albums (SNEP)[87] | 44 |

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[88] | 61 |

| Greek International Albums (IFPI)[89] | 11 |

| Irish Albums (IRMA)[90] | 93 |

| Italian Albums (FIMI)[91] | 45 |

| Japanese Albums (Oricon)[92] | 89 |

| Scottish Albums (OCC)[93] | 50 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[94] | 25 |

| Swiss Albums (Schweizer Hitparade)[95] | 37 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[96] | 46 |

| US Billboard 200[97] | 15 |

| US Top Alternative Albums (Billboard)[98] | 2 |

| US Top Rock Albums (Billboard)[99] | 4 |

| US Top Tastemaker Albums (Billboard)[100] | 3 |

Release history

edit| Region | Date | Format(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | April 23, 2010 | |

| Switzerland | ||

| Austria | ||

| Poland | ||

| Netherlands | ||

| Various | April 26, 2010 | |

| United States | April 27, 2010 | |

| Canada | ||

| Italy | ||

| Ireland | ||

| Australia | April 30, 2010 | |

| United Kingdom | May 3, 2010 | |

| Japan | May 11, 2010 | |

| Brazil |

References

edit- ^ a b c "Discography: Hole". Mercury Records. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012.

- ^ "Album: Hole, Nobody's Daughter (Mercury)". The Independent. May 2, 2010. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (April 26, 2010). "Nobody's Daughter". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ "Courtney Love". On The Record. May 10, 2010. Fuse. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Powers, Ashley (March 10, 2007). "Rehab center is suing Courtney Love over fees". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ Lash, Jolie (November 17, 2005). "Jolie Lash meets Courtney Love". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 19, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Courtney Love back to work on new songs". NME. November 18, 2005. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Love Wants Her Throne Back". Billboard. October 20, 2006. Archived from the original on January 22, 2016.

- ^ Lash, Jolie (February 3, 2006). "Courtney Love Is Cleared, Ready to Rock". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b Taylor, Chris (September 30, 2006). "New Courtney Love Songs Like 'Old Bob Dylan'". Gigwise. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (June 17, 2009). "Courtney Love To Resurrect Hole For 'Nobody's Daughter'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Courtney Love gets UK stars on new album". NME. January 10, 2006. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c Eliscu, Jenny (November 12, 2009). "Courtney Love Explores Greed, Vengeance, and Feminism on 'Nobody's Daughter'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c Browne, David (January 26, 2019). "Linda Perry: My Life in 15 Songs". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Bob Dylan: Courtney's New Muse". Spin. March 3, 2006. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Courtney Love Makes Shock Live Appearance". NME. May 1, 2006. Archived from the original on March 30, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ "Courtney Love meets 2,000 lesbians". The Advocate. May 2, 2006. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ Scrapbook Editors. "The Return Of Courtney Love". Channel4.com. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "We Remember to Eat, Courtney Love Joins Us". Rolling Stone. October 31, 2006. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008.

- ^ "Forget 'Idol,' Courtney Love Gets Coldplayed". Access Hollywood. February 9, 2007. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Courtney Love makes live return". NME. June 2, 2007. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014.

- ^ Edwards, Tom (July 17, 2007). "Courtney Love at London Bush Hall, Mon 09 Jul". Drowned in Sound. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008.

- ^ Webb, Dan (July 22, 2018). "LT Wade talks fish & chips and Courtney Love". SunGenre. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Courtney Love To Play Free Show @ Hiro Ballroom Tonight". Adweek. July 12, 2007. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ Raymond, Kitty (July 25, 2007). "Exchanging Digits?". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 22 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Courtney Love scraps new album". NME. May 16, 2008. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bozza, Anthony (April 18, 2010). "Courtney Love's Improbable Second Act". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Martin, Daniel (June 17, 2009). "The Return Of Hole – Courtney Love's In-The-Studio Video Diary". NME. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (June 23, 2009). "Courtney Love's Hole reunion questioned by former bassist". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Sarah (May 13, 2010). "Courtney Love". FasterLouder. Archived from the original on June 9, 2014.

- ^ Harding, Cortney (April 2, 2010). "Courtney Love: Fixing a Hole". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 22, 2014.

- ^ a b c Stewart, Allison (July 11, 2013). "Courtney Love is back and still wants the world". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013.

- ^ a b c Nobody's Daughter (Album liner notes). Hole. Mercury Records. 2010. pp. 1–4. B0014222-02.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Paine, Kelsey (March 25, 2010). "Hole Reveal New Album Art and Tracklist". Spin. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (March 26, 2010). "Hole Reveal Track List, Cover for April 27's 'Nobody's Daughter'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ Savage, Mark (May 7, 2010). "Twenty minutes with Courtney Love". BBC News. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (January 5, 2009). "Courtney Love album sponsored by tequila and tampon brands". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ Magee, Kate (January 27, 2010). "Courtney Love hires Stoked PR European music comeback". PRWeek. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012.

- ^ Pastorek, Whitney (February 16, 2010). "Courtney Love finds new home for Hole: 'Nobody's Daughter' hits stores April 27". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015.

- ^ "Courtney Love Returns With Nobody'ss Daughter, First Hole Album in Ten Years, Out in April on Mercury Records in the US". Universal Music Group. March 12, 2010. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- ^ a b ""Skinny Little Bitch", o vídeo mais barite de Courtney Love". TecoApple (in Portuguese). April 28, 2010. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Hole – Samantha". YouTube. May 4, 2010. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Peisner, David (July 9, 2009). "Q&A: Hole's Eric Erlandson". Spin. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (July 16, 2009). "Courtney Love slams Hole co-founder in Twitter rant". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Hole :: Nobody's Daughter". Holerock.net. Universal Music Group. Archived from the original on March 22, 2010.

- ^ a b "Exclusive Interview with Eric Erlandson". GrungeReport.net. April 14, 2010. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010.

- ^ Pelly, Jenn (May 1, 2014). "Courtney Love". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Press Office – The Week's Guests week 6". BBC. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- ^ "Courtney Love plays first Hole gig in 11 years". NME. February 18, 2010. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Today in Music History: Happy Birthday, Courtney Love". The Current. Minneapolis, Minnesota. July 9, 2019. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Hole". Paradiso (in Dutch). February 21, 2010. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Paul Weller, Kasabian, Hole, The Specials to perform at Shockwaves NME Awards". NME. February 21, 2010. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Courtney Love to bring Hole to South by Southwest". The Independent. London. February 24, 2010. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012.

- ^ Young, Alex (May 3, 2010). "Hole announces more U.S. dates". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Bumbershoot girds for Drake quake". The Seattle Times. June 22, 2010. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ Zwickel, Jonathan (September 7, 2010). "10 Best Moments of Seattle's Bumbershoot Fest". Spin. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ Lewis, Randy (May 5, 2010). "Atlanta rapper B.o.B.'s 'Adventure' at No. 1". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014.

- ^ "On the charts: The National, Sleigh Bells make an impact in a sloooooooow sales week". Los Angeles Times. May 19, 2010. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014.

- ^ "The 20 biggest flops of 2010". Metromix. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011.

- ^ "Courtney Love: damage limitation". The Telegraph. April 1, 2010. Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Nobody's Daughter by Hole". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Nobody's Daughter – Hole". AllMusic. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Helen (April 27, 2010). "Hole: Nobody's Daughter, CD review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016.

- ^ Greenblatt, Leah (April 23, 2010). "Nobody's Daughter Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Hunter-Tilney, Ludovic (April 30, 2010). "Hole: Nobody's Daughter". Financial Times. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Caroline (April 29, 2010). "Hole: Nobody's Daughter". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (June 2010). "Robert Christgau's Consumer Guide". MSN Music. p. 22. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Edwards, Tom (May 7, 2010). "Album Review: Hole – 'Nobody's Daughter'". NME. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Petrusich, Amanda (April 27, 2010). "Hole: Nobody's Daughter". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c Sheffield, Rob (April 26, 2010). "Nobody's Daughter". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Reilly, Phoebe (June 2010). "Reviews: Nobody's Daughter". Spin. Vol. 26, no. 5. p. 88. ISSN 0886-3032.

- ^ Paphides, Pete (April 30, 2010). "Hole: Nobody's Daughter". The Times. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ a b "Critic Reviews for Nobody's Daughter". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 22, 2016.

- ^ Davis, Petra (May 11, 2010). "Nobody's Daughter". The Quietus. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020.

- ^ Gill, Jaime (April 26, 2010). "Review – Nobody's Daughter". BBC Music. Archived from the original on May 6, 2010.

- ^ Lipshutz, Jason (April 26, 2010). "Hole, Nobody's Daughter review". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015.

- ^ Hermes, Will (May 5, 2010). "Courtney Love And Kate Nash: On The Shoulders Of Hole". NPR. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- ^ Martins, Chris (May 30, 2013). "Courtney Love May Call Next Hole-less Album 'Died Blonde'". Spin. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013.

- ^ "Nobody's Daughter (Bonus Track Version) by Hole". iTunes. Archived from the original on April 30, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ^ "Nobody's Daughter【CD】-Hole Release Country: Japan | Alternative & Punk | Rock & Pop | Music | HMV ONLINE Buy Music & Movie CD / DVD". HMV Japan. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- ^ a b Nobody's Daughter (CD). Hole. Mercury Records. 2010. LC 00268.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Baltin, Steve (March 28, 2012). "Dead Sara Gears Up for Breakout Year | Music News". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Hole – Nobody's Daughter". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Hole – Nobody's Daughter" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Hole – Nobody's Daughter" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Hole Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Hole – Nobody's Daughter". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Hole – Nobody's Daughter" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Greekcharts.com – Hole – Nobody's Daughter". Hung Medien. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Irish-charts.com – Discography Hole". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – Hole – Nobody's Daughter". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ ホールのアルバム売り上げランキング [Hole album sales ranking] (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Hole – Nobody's Daughter". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Hole – Nobody's Daughter". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Hole Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Hole Chart History (Top Alternative Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Hole Chart History (Top Rock Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Hole Chart History (Top Tastemaker Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved April 22, 2020.