The follicle-stimulating hormone receptor or FSH receptor (FSHR) is a transmembrane receptor that interacts with the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and represents a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). Its activation is necessary for the hormonal functioning of FSH. FSHRs are found in the ovary, testis, and uterus.

FSHR gene

editThe gene for the FSHR is found on chromosome 2 p21 in humans. The gene sequence of the FSHR consists of about 2,080 nucleotides.[5]

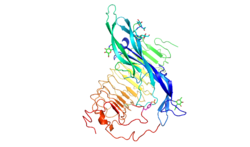

Receptor structure

editThe FSHR consists of 695 amino acids and has a molecular mass of about 76 kDa.[5] Like other GPCRs, the FSH-receptor possesses seven membrane-spanning domains or transmembrane helices.

- The extracellular domain of the receptor contains 11 leucine-rich repeats and is glycosylated. It has two subdomains, a hormone-binding subdomain followed by a signal-specificity subdomain.[6] The hormone-binding subdomain is responsible for the high-affinity hormone binding, and the signal-specificity subdomain, containing a sulfated tyrosine at position 335 (sTyr) in a hinge loop, is required for the hormone activity.[7]

- The transmembrane domain contains two highly conserved cysteine residues that build disulfide bonds to stabilize the receptor structure. A highly conserved Asp-Arg-Tyr triplet motif is present in GPCR family members in general and may be of importance to transmit the signal. In FSHR and its closely related other glycoprotein hormone receptor members (LHR and TSHR), this conserved triplet motif is a variation Glu-Arg-Trp sequence.[8]

- The C-terminal domain is intracellular and brief, rich in serine and threonine residues for possible phosphorylation.

Ligand binding and signal transduction

editUpon initial binding to the LRR region of FSHR, FSH reshapes its conformation to form a new pocket. FSHR then inserts its sulfotyrosine from the hinge loop into the pockets and activates the 7-helical transmembrane domain.[6] This event leads to a transduction of the signal that activates the Gs protein that is bound to the receptor internally. With FSH attached, the receptor shifts conformation and, thus, mechanically activates the G protein, which detaches from the receptor and activates the cAMP system.[9][10]

It is believed that a receptor molecule exists in a conformational equilibrium between active and inactive states. The binding of FSH to the receptor shifts the equilibrium between active and inactive receptors. FSH and FSH-agonists shift the equilibrium in favor of active states; FSH antagonists shift the equilibrium in favor of inactive states.

Phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinases

editCyclic AMP-dependent protein kinases (protein kinase A) are activated by the signal chain coming from the Gs protein (that was activated by the FSH-receptor) via adenylate cyclase and cyclic AMP (cAMP).[9][10]

These protein kinases are present as tetramers with two regulatory units and two catalytic units. Upon binding of cAMP to the regulatory units, the catalytic units are released and initiate the phosphorylation of proteins, leading to the physiologic action. The cyclic AMP-regulatory dimers are degraded by phosphodiesterase and release 5’AMP. DNA in the cell nucleus binds to phosphorylated proteins through the cyclic AMP response element (CRE), which results in the activation of genes.[5]

The signal is amplified by the involvement of cAMP and the resulting phosphorylation. The process is modified by prostaglandins. Other cellular regulators are participate are the intracellular calcium concentration modified by phospholipase, nitric acid, and other growth factors.

The FSH receptor can also activate the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK).[11] In a feedback mechanism, these activated kinases phosphorylate the receptor.

Action

editIn the ovary, the FSH receptor is necessary for follicular development and expressed on the granulosa cells.[5]

In the male, the FSH receptor has been identified on the Sertoli cells that are critical for spermatogenesis.[12]

The FSHR is expressed during the luteal phase in the secretory endometrium of the uterus.[13]

FSH receptor is selectively expressed on the surface of the blood vessels of a wide range of carcinogenic tumors.[14]

Receptor regulation

editUpregulation

editUpregulation refers to the increase in the number of receptor sites on the membrane. Estrogen upregulates FSH receptor sites. In turn, FSH stimulates granulosa cells to produce estrogens. This synergistic activity of estrogen and FSH allows for follicle growth and development in the ovary.[citation needed]

Desensitization

editThe FSHR become desensitized when exposed to FSH for some time. A key reaction of this downregulation is the phosphorylation of the intracellular (or cytoplasmic) receptor domain by protein kinases.[15] This process uncouples Gs protein from the FSHR. Another way to desensitize is to uncouple the regulatory and catalytic units of the cAMP system.[citation needed]

Downregulation

editDownregulation refers to the decrease in the number of receptor sites. This can be accomplished by metabolizing bound FSHR sites. The bound FSH-receptor complex is brought by lateral migration to a "coated pit," where such units are concentrated and then stabilized by a framework of clathrins. A pinched-off coated pit is internalized and degraded by lysosomes. Proteins may be metabolized or the receptor can be recycled.

Modulators

editAntibodies to FSHR can interfere with FSHR activity.

FSH abnormalities

editSome patients with ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome may have mutations in the gene for FSHR, making them more sensitive to gonadotropin stimulation.[16]

Women with 46 XX gonadal dysgenesis experience primary amenorrhea with hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. There are forms of 46 xx gonadal dysgenesis wherein abnormalities in the FSH-receptor have been reported and are thought to be the cause of the hypogonadism.[17]

Polymorphism may affect FSH receptor populations and lead to poorer responses in infertile women receiving FSH medication for IVF.[18]

Alternative splicing of the FSHR gene may be implicated in subfertility in males[19]

Ligands

editFollicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is an agonist of the FSHR.

Small-molecule positive allosteric modulators of the FSHR have been developed.[20]

History

editAlfred G. Gilman and Martin Rodbell received the 1994 Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology for "their discovery of G-proteins and the role of these proteins in signal transduction in cells".[21][22]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000170820 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000032937 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c d Simoni M, Gromoll J, Nieschlag E (Dec 1997). "The follicle-stimulating hormone receptor: biochemistry, molecular biology, physiology, and pathophysiology". Endocrine Reviews. 18 (6): 739–73. doi:10.1210/edrv.18.6.0320. PMID 9408742.

- ^ a b Jiang X, Liu H, Chen X, Chen PH, Fischer D, Sriraman V, et al. (Jul 2012). "Structure of follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with the entire ectodomain of its receptor". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (31): 12491–6. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10912491J. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206643109. PMC 3411987. PMID 22802634.

- ^ Costagliola S, Panneels V, Bonomi M, Koch J, Many MC, Smits G, et al. (Feb 2002). "Tyrosine sulfation is required for agonist recognition by glycoprotein hormone receptors". The EMBO Journal. 21 (4): 504–13. doi:10.1093/emboj/21.4.504. PMC 125869. PMID 11847099.

- ^ Jiang X, Dias JA, He X (Jan 2014). "Structural biology of glycoprotein hormones and their receptors: insights to signaling". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 382 (1): 424–51. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.021. PMID 24001578.

- ^ a b De Pascali F, Tréfier A, Landomiel F, Bozon V, Bruneau G, Yvinec R, et al. (2018). "Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor: Advances and Remaining Challenges". International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. 338: 1–58. arXiv:1808.01965. doi:10.1016/bs.ircmb.2018.02.001. ISBN 978-0-12-813772-7. PMID 29699689.

- ^ a b Casarini L, Crépieux P (2019). "Molecular Mechanisms of Action of FSH". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 10: 305. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00305. hdl:11380/1181065. PMID 31139153.

- ^ Piketty V, Kara E, Guillou F, Reiter E, Crepieux P (2006). "Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation independently of beta-arrestin- and dynamin-mediated FSH receptor internalization". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 4: 33. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-4-33. PMC 1524777. PMID 16787538.

- ^ Asatiani K, Gromoll J, Eckardstein SV, Zitzmann M, Nieschlag E, Simoni M (Jun 2002). "Distribution and function of FSH receptor genetic variants in normal men". Andrologia. 34 (3): 172–6. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0272.2002.00493.x. PMID 12059813. S2CID 21090038.

- ^ La Marca A, Carducci Artenisio A, Stabile G, Rivasi F, Volpe A (Dec 2005). "Evidence for cycle-dependent expression of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor in human endometrium". Gynecological Endocrinology. 21 (6): 303–6. doi:10.1080/09513590500402756. PMID 16390776. S2CID 24690912.

- ^ Radu A, Pichon C, Camparo P, Antoine M, Allory Y, Couvelard A, et al. (Oct 2010). "Expression of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor in tumor blood vessels". The New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (17): 1621–30. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1001283. PMID 20961245.

- ^ Manna PR, Pakarainen P, Rannikko AS, Huhtaniemi IT (November 1998). "Mechanisms of desensitization of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) action in a murine granulosa cell line stably transfected with the human FSH receptor complementary deoxyribonucleic acid". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 146 (1–2): 163–176. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(98)00156-7. PMID 10022774.

- ^ Delbaere A, Smits G, De Leener A, Costagliola S, Vassart G (Apr 2005). "Understanding ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome". Endocrine. 26 (3): 285–90. doi:10.1385/ENDO:26:3:285. PMID 16034183. S2CID 7607365.

- ^ Aittomäki K, Lucena JL, Pakarinen P, Sistonen P, Tapanainen J, Gromoll J, et al. (Sep 1995). "Mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene causes hereditary hypergonadotropic ovarian failure". Cell. 82 (6): 959–68. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90275-9. PMID 7553856. S2CID 14748261.

- ^ Loutradis D, Patsoula E, Minas V, Koussidis GA, Antsaklis A, Michalas S, et al. (Apr 2006). "FSH receptor gene polymorphisms have a role for different ovarian response to stimulation in patients entering IVF/ICSI-ET programs". Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 23 (4): 177–84. doi:10.1007/s10815-005-9015-z. PMC 3454958. PMID 16758348.

- ^ Song GJ, Park YS, Lee YS, Lee CC, Kang IS (Mar 2002). "Alternatively spliced variants of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene in the testis of infertile men". Fertility and Sterility. 77 (3): 499–504. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03221-6. PMID 11872202.

- ^ Nataraja S, Yu H, Guner J, Palmer S (2020). "Discovery and Preclinical Development of Orally Active Small Molecules that Exhibit Highly Selective Follicle Stimulating Hormone Receptor Agonism". Front Pharmacol. 11: 602593. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.602593. PMC 7845544. PMID 33519465.

- ^ Gilman AG (1994). "G Proteins and Regulation of Adenylyl Cyclase". Nobel Lecture.

- ^ Rodbell M (1994). "Signal Transduction: Evolution of an Idea". Nobel Lecture.