List of Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launches (2010–2019)

From June 2010, to the end of 2019, Falcon 9 was launched 77 times, with 75 full mission successes, one partial failure and one total loss of the spacecraft. In addition, one rocket and its payload were destroyed on the launch pad during the fueling process before a static fire test was set to occur. Falcon Heavy was launched three times, all successful.

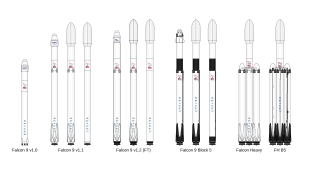

The first Falcon 9 version, Falcon 9 v1.0, was launched five times from June 2010, to March 2013, its successor Falcon 9 v1.1 15 times from September 2013, to January 2016, and the Falcon 9 Full Thrust (through Block 4) 36 times from December 2015, to June 2018. The latest Full Thrust variant, Block 5, was introduced in May 2018,[1] and launched 21 times before the end of 2019.

Statistics

editRocket configurations

edit- Falcon 9 v1.0

- Falcon 9 v1.1

- Falcon 9 Full Thrust

- Falcon 9 FT (reused)

- Falcon 9 Block 5

- Falcon 9 B5 (reused)

- Falcon Heavy

Launch sites

editLaunch outcomes

edit- Loss before launch

- Loss during flight

- Partial failure

- Success (commercial and government)

- Success (Starlink)

Booster landings

editLaunches

edit2010 to 2013

editFlight No. |

Date and time (UTC) |

Version, booster[a] [2][3] |

Launch site |

Payload | Payload mass | Orbit | Customer | Launch outcome |

Booster landing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 June 2010 18:45 |

F9 v1.0 B0003 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Dragon Spacecraft Qualification Unit | Unknown | LEO | SpaceX | Success | Failure (parachute) |

| First flight of Falcon 9 v1.0.[4][2][3] Used a boilerplate version of Dragon capsule which was not designed to separate from the second stage.(more details) Attempted to recover the first stage by parachuting it into the ocean, but it burned up on reentry, before the parachutes even got to deploy.[5][6][7] | |||||||||

| 2 | 8 December 2010 15:43[8] |

F9 v1.0 B0004 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX COTS Demo Flight 1 (Dragon C101) | Unknown | LEO | NASA (COTS) | Success | Failure (parachute) |

| Maiden flight of SpaceX's Dragon capsule, consisting of over 3 hours of testing thruster maneuvering and then reentry.[9] Second flight of Falcon 9 v1.0.[2][3] Attempted to recover the first stage by parachuting it into the ocean, but it disintegrated upon reentry, again before the parachutes were deployed.[6][10](more details) It also included eight CubeSats,[11] and a wheel of Brouère cheese. Before the launch, SpaceX discovered that there was a crack in the nozzle of the 2nd stage's Merlin vacuum engine. SpaceX cut off the end of the nozzle and got NASA's approval to fly in this configuration.[12] | |||||||||

| 3 | 22 May 2012 07:44[13] |

F9 v1.0 B0005 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX COTS Demo Flight 2[14] (Dragon C102) |

525 kg (1,157 lb)[15] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (COTS) | Success[16] | No attempt |

| The Dragon spacecraft demonstrated a series of tests before it was allowed to approach the International Space Station. Two days later, it became the first commercial spacecraft to board the ISS.[13] (more details) | |||||||||

| 4 | 8 October 2012 00:35[17] |

F9 v1.0 B0006 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-1[18] (Dragon C103) |

4,700 kg (10,400 lb) (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | No attempt |

| Orbcomm-OG2[19] | 172 kg (379 lb)[20] | LEO | Orbcomm | Partial failure[21] | |||||

| CRS-1 was successful, but the secondary payload was inserted into an abnormally low orbit and subsequently lost. This was due to one of the nine Merlin engines shutting down during the launch, and NASA declining a second reignition, as per ISS visiting vehicle safety rules, the primary payload owner is contractually allowed to decline a second reignition. NASA stated that this was because SpaceX could not guarantee a high enough likelihood of the second stage completing the second burn successfully which was required to avoid any risk of secondary payload's collision with the ISS.[22][23][24] | |||||||||

| 5 | 1 March 2013 15:10 |

F9 v1.0 B0007 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-2[18] (Dragon C104) |

4,877 kg (10,752 lb) (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | No attempt |

| Last launch of the original Falcon 9 v1.0 launch vehicle, first use of the unpressurized trunk section of Dragon.[25] | |||||||||

| 6 | 29 September 2013 16:00[26] |

F9 v1.1 B1003 |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | CASSIOPE[18][27] | 500 kg (1,100 lb) | Polar orbit LEO | MDA | Success[26] | Failure (ocean)[b] |

| First commercial mission with a private customer, first launch from Vandenberg, and demonstration flight of Falcon 9 v1.1 with an improved 13-tonne to LEO capacity.[25] After separation from the second stage carrying Canadian commercial and scientific satellites, the first stage booster performed a controlled reentry,[28] and an ocean touchdown test for the first time. This provided good test data, even though the booster started rolling as it neared the ocean, leading to the shutdown of the central engine as the roll depleted it of fuel, resulting in a hard impact with the ocean.[26] This was the first known attempt of a rocket engine being lit to perform a supersonic retro propulsion, and allowed SpaceX to enter a public-private partnership with NASA and its Mars entry, descent, and landing technologies research projects.[29] (more details) This was also the first orbital launch using SpaceX's upgraded Merlin 1D rocket engine.[30] | |||||||||

| 7 | 3 December 2013 22:41[31] |

F9 v1.1 B1004 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SES-8[18][32][33] | 3,170 kg (6,990 lb) | GTO | SES | Success[34] | No attempt [35] |

| First geostationary transfer orbit (GTO) launch for Falcon 9,[32] and first successful reignition of the second stage.[36] SES-8 was inserted into a supersynchronous transfer orbit of 79,341 km (49,300 mi) in apogee with an inclination of 20.55° to the equator. | |||||||||

2014

editWith six launches, SpaceX became the second most prolific American company in terms of 2014 launches, behind Atlas V launch vehicle.[37]

Flight No. |

Date and time (UTC) |

Version, booster[a][3] |

Launch site |

Payload[c] | Payload mass | Orbit | Customer | Launch outcome |

Booster landing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 6 January 2014 22:06[38] |

F9 v1.1 B1005 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Thaicom 6[18] | 3,325 kg (7,330 lb) | GTO | Thaicom | Success[39] | No attempt [40] |

| The Thai communication satellite was the second GTO launch for Falcon 9. The USAF evaluated launch data from this flight as part of a separate certification program for SpaceX to qualify to fly military payloads, but found that the launch had "unacceptable fuel reserves at engine cutoff of the stage 2 second burnoff".[41] Thaicom-6 was inserted into a supersynchronous transfer orbit of 90,039 km (55,948 mi) in apogee with an inclination of 22.46° to the equator. | |||||||||

| 9 | 18 April 2014 19:25[17] |

F9 v1.1 B1006 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-3[18] (Dragon C105) |

2,296 kg (5,062 lb)[42] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Controlled (ocean)[b][43] |

| Following second-stage separation, SpaceX conducted a second controlled-descent test of the discarded booster vehicle and achieved the first successful controlled ocean touchdown of a liquid-rocket-engine orbital booster.[44][45] Following the soft touchdown, the first stage tipped over as expected and was destroyed. This was the first Falcon 9 booster to fly with extensible landing legs and the first Dragon mission with the Falcon 9 v1.1 launch vehicle. This flight also launched the ELaNa 5 mission for NASA as a secondary payload.[46][47] | |||||||||

| 10 | 14 July 2014 15:15 |

F9 v1.1 B1007 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Orbcomm-OG2-1 (6 satellites)[18] |

1,316 kg (2,901 lb) | LEO | Orbcomm | Success[48] | Controlled (ocean)[b][43] |

| Payload included six satellites weighing 172 kg (379 lb) each and two 142 kg (313 lb) mass simulators.[20][49] Equipped for the second time with landing legs, the first-stage booster successfully conducted a controlled-descent test consisting of a burn for deceleration from hypersonic velocity in the upper atmosphere, a reentry burn, and a final landing burn before soft-landing on the ocean surface.[50] | |||||||||

| 11 | 5 August 2014 08:00 |

F9 v1.1 B1008 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | AsiaSat 8[18][51][52] | 4,535 kg (9,998 lb) | GTO | AsiaSat | Success[53] | No attempt [54] |

| First time SpaceX managed a launch site turnaround between two flights of under a month (22 days). GTO launch of the large communication satellite from Hong Kong did not allow for propulsive return-over-water and controlled splashdown of the first stage.[54] | |||||||||

| 12 | 7 September 2014 05:00 |

F9 v1.1 B1011 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | AsiaSat 6[18][51][55] | 4,428 kg (9,762 lb) | GTO | AsiaSat | Success[56] | No attempt |

| Launch was delayed for two weeks for additional verifications after a malfunction observed in the development of the F9R Dev1 prototype.[57] GTO launch of the heavy payload did not allow for controlled splashdown.[58] | |||||||||

| 13 | 21 September 2014 05:52[17] |

F9 v1.1 B1010 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-4[18] (Dragon C106.1) |

2,216 kg (4,885 lb)[59] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success[60] | Failure (ocean)[b][61] |

| Fourth attempt of a soft ocean touchdown,[62] but the booster ran out of liquid oxygen.[61] Detailed thermal imaging infrared sensor data was collected however by NASA, as part of a joint arrangement with SpaceX as part of research on retropropulsive deceleration technologies for developing new approaches to Martian atmospheric entry.[62] | |||||||||

2015

editWith seven launches in 2015, Falcon 9 was the second most launched American rocket behind Atlas V.[63]

Flight No. |

Date and time (UTC) |

Version, booster[a] |

Launch site |

Payload[c] | Payload mass | Orbit | Customer | Launch outcome |

Booster landing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 10 January 2015 09:47[64] |

F9 v1.1 B1012 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-5[65] (Dragon C107) |

2,395 kg (5,280 lb)[66] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success[67] | Failure (JRTI) |

| Following second-stage separation, SpaceX attempted to return the first stage for the first time to a 90 m × 50 m (300 ft × 160 ft) floating platform — called the autonomous spaceport drone ship. The test achieved many objectives and returned a large amount of data, but the grid-fin control surfaces used for the first time for more precise reentry positioning ran out of hydraulic fluid for its control system a minute before landing, resulting in a landing crash.[68] | |||||||||

| 15 | 11 February 2015 23:03[69] |

F9 v1.1 B1013 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | DSCOVR[65][70] | 570 kg (1,260 lb) | Sun–Earth L1 insertion | Success | Controlled (ocean)[b] | |

| First launch under USAF's OSP 3 launch contract.[71] First SpaceX launch to put a satellite beyond a geostationary transfer orbit, first SpaceX launch into interplanetary space, and first SpaceX launch of an American research satellite. The first stage made a test flight descent to an over-ocean landing within 10 m (33 ft) of its intended target.[72] The satellite launched into a 187 km x 1,241,000 km insertion orbit toward the Sun-Earth L1 point.[73] | |||||||||

| 16 | 2 March 2015 03:50[17][74] |

F9 v1.1 B1014 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | 4,159 kg (9,169 lb) | GTO | Success | No attempt[75] | ||

| The launch was Boeing's first conjoined launch of a lighter-weight dual-commsat stack that was specifically designed to take advantage of the lower-cost SpaceX Falcon 9 launch vehicle.[76][77] Per satellite, launch costs were less than US$30 million.[78] The ABS satellite reached its final destination ahead of schedule and started operations on 10 September 2015.[79] | |||||||||

| 17 | 14 April 2015 20:10[17] |

F9 v1.1 B1015 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-6[65] (Dragon C108.1) |

1,898 kg (4,184 lb)[80] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Failure (JRTI) |

| After second-stage separation, a controlled-descent test was attempted with the first stage. After the booster contacted the ship, it tipped over due to excess lateral velocity caused by a stuck throttle valve that delayed downthrottle at the correct time.[81][82] | |||||||||

| 18 | 27 April 2015 23:03[83] |

F9 v1.1 B1016 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | TürkmenÄlem 52°E / MonacoSAT[65][84] | 4,707 kg (10,377 lb) | GTO | Turkmenistan National Space Agency[85] |

Success | No attempt[86] |

| Original intended launch was delayed over a month after an issue with the helium pressurisation system was identified on similar parts in the assembly plant.[87] Subsequent launch successfully positioned this first Turkmen satellite at 52.0° east. | |||||||||

| 19 | 28 June 2015 14:21[17][88] |

F9 v1.1 B1018 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-7[65] (Dragon C109) |

1,952 kg (4,303 lb)[89] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Failure[90] | Precluded (drone ship)[91] |

| Launch performance was nominal until an overpressure incident in the second-stage LOX tank, leading to vehicle breakup at T+150 seconds. Dragon capsule survived the explosion but was lost upon splashdown as its software did not contain provisions for parachute deployment on launch vehicle failure.[92](more details) The drone ship Of Course I Still Love You was towed out to sea to prepare for a landing test so this mission was its first operational assignment.[93] | |||||||||

| 20 | 22 December 2015 01:29[94] |

F9 FT B1019 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Orbcomm-OG2-2 (11 satellites)[18][94] |

2,034 kg (4,484 lb) | LEO | Orbcomm | Success | Success (LZ‑1) |

| Payload included eleven satellites weighing 172 kg (379 lb) each,[20] and a 142 kg (313 lb) mass simulator.[49] First launch of the upgraded v1.1 version, with a 30% power increase.[95] Orbcomm had originally agreed to be the third flight of the enhanced-thrust rocket,[96] but the change to the maiden flight position was announced in October 2015.[95] SpaceX received a permit from the FAA to land the booster on solid ground at SpaceX Landing Zone 1 at Cape Canaveral[97] and succeeded for the first time ever in its history on this maiden ground landing attempt.[98] This booster, serial number B1019, is now on permanent display outside SpaceX's headquarters in Hawthorne, California, at the intersection of Crenshaw Boulevard and Jack Northrop Avenue.[99] (more details) | |||||||||

2016

editWith eight successful launches for 2016, SpaceX equalled Atlas V for most American rocket launches for the year.[100]

Flight No. |

Date and time (UTC) |

Version, booster[a] |

Launch site |

Payload[c] | Payload mass | Orbit | Customer | Launch outcome |

Booster landing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 17 January 2016 18:42[17] |

F9 v1.1 B1017[3] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | Jason-3[65][101] | 553 kg (1,219 lb) | LEO | Success | Failure (JRTI) | |

| First launch of NASA and NOAA joint science mission under the NLS II launch contract (not related to NASA CRS or USAF OSP3 contracts) and last launch of the Falcon 9 v1.1 launch vehicle. The Jason-3 satellite was successfully deployed to target orbit.[102] SpaceX attempted for the first time to recover the first-stage booster on its new Pacific autonomous drone ship, but after a soft landing on the ship, the lockout on one of the landing legs failed to latch and the booster fell over and exploded.[103][104] | |||||||||

| 22 | 4 March 2016 23:35[17] |

F9 FT B1020[105] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SES-9[65][106][107] | 5,271 kg (11,621 lb) | GTO | SES | Success | Failure (OCISLY) |

| Second launch of the enhanced Falcon 9 Full Thrust launch vehicle.[95] SpaceX attempted for the first time to recover a booster from a GTO launch to a drone ship.[108] Successful landing was not expected due to low fuel reserves[109] and the booster "landed hard".[110] But the controlled-descent, atmospheric re-entry and navigation to the drone ship were successful and returned significant test data on bringing back high-energy Falcon 9 boosters.[111] | |||||||||

| 23 | 8 April 2016 20:43[17] |

F9 FT B1021.1[112] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-8[65][107] (Dragon C110.1) |

3,136 kg (6,914 lb)[113] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success[114] | Success (OCISLY) |

| Dragon carried over 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) of supplies and delivered the inflatable Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) to the ISS for two years of in-orbit tests.[115] The rocket's first stage landed smoothly on SpaceX's autonomous spaceport drone ship at 9 minutes after liftoff, making this the first successful landing of a rocket booster on a ship at sea from an orbital launch.[116] The first stage B1021 later became the first orbital booster to be reused when it launched SES-10 on 30 March 2017.[112] A month later, the Dragon spacecraft returned a downmass containing astronaut's Scott Kelly biological samples from his year-long mission on ISS.[117](more details) | |||||||||

| 24 | 6 May 2016 05:21[17] |

F9 FT B1022[118] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | JCSAT-14[119] | 4,696 kg (10,353 lb)[120] | GTO | SKY Perfect JSAT Group | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| First time SpaceX launched a Japanese satellite, and first time a booster landed successfully after launching a payload into a GTO.[121] As this flight profile has a smaller margin for the booster recovery, the first stage re-entered Earth's atmosphere faster than for previous landings, with five times the heating power.[122][123] | |||||||||

| 25 | 27 May 2016 21:39[124] |

F9 FT B1023.1[125] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Thaicom 8[126][127] | 3,100 kg (6,800 lb)[128] | GTO | Thaicom | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| Second successful return from a GTO launch,[129] after launching Thaicom 8 towards 78.5° east.[130] Later became the first booster to be reflown after being recovered from a GTO launch. THAICOM 8 was delivered to a supersynchronous transfer orbit of 91,000 km (57,000 mi).[131] | |||||||||

| 26 | 15 June 2016 14:29[17] |

F9 FT B1024[105] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | 3,600 kg (7,900 lb) | GTO | Success | Failure (OCISLY) | ||

| One year after pioneering this technique on Flight 16, Falcon again launched two Boeing 702SP gridded ion thruster satellites at 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) each,[132][133] in a dual-stack configuration, with the two customers sharing the rocket and mission costs.[79] First-stage landing attempt on drone ship failed due to low thrust on one of the three landing engines;[134] a sub-optimal path led to the stage running out of propellant just above the deck of the landing ship,[135] slamming to the drone ship, breaking a leg, and falling over. | |||||||||

| 27 | 18 July 2016 04:45[17] |

F9 FT B1025.1[125] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-9[65][136] (Dragon C111.1) |

2,257 kg (4,976 lb)[137] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Success (LZ‑1) |

| Cargo to ISS included an International Docking Adapter (IDA-2) and total payload with reusable Dragon Capsule was 6,457 kg (14,235 lb). Second successful first-stage landing on a ground pad.[138] | |||||||||

| 28 | 14 August 2016 05:26 |

F9 FT B1026[105] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | JCSAT-16 | 4,600 kg (10,100 lb) | GTO | SKY Perfect JSAT Group | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| First attempt to land from a ballistic trajectory using a single-engine landing burn, as all previous landings from a ballistic trajectory had fired three engines on the final burn. The latter provides more braking force but subjects the vehicle to greater structural stresses, while the single-engine landing burn takes more time and fuel while allowing more time during final descent for corrections.[139] | |||||||||

| N/A[d] | 3 September 2016 07:00[140] |

F9 FT B1028 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | AMOS-6 | 5,500 kg (12,100 lb) | GTO | Spacecom | Precluded (pre-flight failure) | Precluded |

| The rocket and the AMOS-6 payload were lost in a launch pad explosion on 1 September 2016, during propellant filling procedures before a static fire test.[141][142] The pad was clear of personnel, and there were no injuries.[143] SpaceX released an official statement in January 2017, indicating that the cause of the failure was a buckled liner in several of the composite overwrapped pressure vessel (COPV) (used to store helium which pressurizes the stage's propellant tanks), causing perforations that allowed liquid and/or solid oxygen to accumulate underneath the lining, which was ignited by friction.[144] Following the explosion, SpaceX has switched to performing static fire tests only without attached payloads.(more details) | |||||||||

2017

editWith 18 launches throughout 2017, SpaceX had the most prolific yearly launch manifest of all rocket families.[145] Five launches in 2017, used pre-flown boosters.

Flight No. |

Date and time (UTC) |

Version, booster[a] |

Launch site |

Payload[c] | Payload mass | Orbit | Customer | Launch outcome |

Booster landing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | 14 January 2017 17:54 |

F9 FT B1029.1[146] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | Iridium NEXT-1 (10 satellites)[147][148] |

9,600 kg (21,200 lb) | Polar LEO | Iridium Communications | Success | Success (JRTI) |

| Return-to-flight mission after the loss of AMOS-6 in September 2016. This was the first launch of a series of Iridium NEXT satellites intended to replace the original Iridium constellation launched in the late 1990s. Each Falcon 9 mission carried 10 satellites, with a goal of 66 plus 9 spare[149] satellites constellation by mid-2018.[150][151] Following the delayed launch of the first two Iridium units with a Dnepr rocket from April 2016, Iridium Communications decided to launch the first batch of 10 satellites with SpaceX instead.[152] Payload comprised ten satellites weighing 860 kg (1,900 lb) each plus a 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) dispenser.[153] | |||||||||

| 30 | 19 February 2017 14:39 |

F9 FT B1031.1[3] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | SpaceX CRS-10[136] (Dragon C112.1) |

2,490 kg (5,490 lb)[154] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Success (LZ‑1) |

| First Falcon 9 flight from the historic LC-39A launchpad at Kennedy Space Center, and first uncrewed launch from LC-39A since Skylab-1.[155] The flight carried supplies and materials to support ISS Expeditions 50 and 51, and third return of first stage booster to landing pad at Cape Canaveral Landing Zone 1.[156] | |||||||||

| 31 | 16 March 2017 06:00 |

F9 FT B1030[157] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | EchoStar 23 | 5,600 kg (12,300 lb)[158] | GTO | EchoStar | Success | No attempt[159] |

| First uncrewed non-station launch from LC-39A since Apollo 6.[155] Launched a communications satellite for broadcast services over Brazil.[160] Due to the payload size launch into a GTO, the booster was expended into the Atlantic Ocean and did not feature landing legs and grid fins.[161] | |||||||||

| 32 | 30 March 2017 22:27 |

F9 FT B1021.2[112] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | SES-10[106][162] | 5,300 kg (11,700 lb)[163] | GTO | SES | Success[164] | Success (OCISLY) |

| First payload to fly on a reused first stage, B1021, previously launched with CRS-8, and first to land intact a second time.[165][164] Additionally, this flight was the first reused rocket to fly from LC-39A since STS-135 and for the first time the payload fairing, used to protect the payload during launch, remained intact after a successful splashdown achieved with thrusters and a steerable parachute.[166][167](more details) | |||||||||

| 33 | 1 May 2017 11:15 |

F9 FT B1032.1[125] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | NROL-76[168] | Classified | LEO[169] | NRO | Success | Success (LZ‑1) |

| First launch under SpaceX's 2015, certification for national security space missions, which allowed SpaceX to contract launch services for classified payloads,[170] and thus breaking the monopoly United Launch Alliance (ULA) held on classified launches since 2006.[171] For the first time, SpaceX offered continuous livestream of first stage booster from liftoff to landing, but omitted second-stage speed and altitude telemetry.[172] | |||||||||

| 34 | 15 May 2017 23:21 |

F9 FT B1034.1[173] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | Inmarsat-5 F4[174] | 6,070 kg (13,380 lb)[175] | GTO | Inmarsat | Success | No attempt [159] |

| The launch was originally scheduled for the Falcon Heavy, but performance improvements allowed the mission to be carried out by an expendable Falcon 9 instead.[176] Inmarsat-5 F4 is Inmarsat's "largest and most complicated communications satellite ever built".[177] Inmarsat 5 F4 was delivered into an arcing supersynchronous transfer orbit of 381 km × 68,839 km (237 mi × 42,775 mi) in altitude, tilted 24.5° to the equator.[178] | |||||||||

| 35 | 3 June 2017 21:07 |

F9 FT B1035.1[179] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | SpaceX CRS-11[136] (Dragon C106.2) |

2,708 kg (5,970 lb)[180] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Success (LZ‑1) |

| This mission delivered Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER),[181] Multiple User System for Earth Sensing Facility (MUSES),[182] Roll Out Solar Array (ROSA),[183] an Advanced Plant Habitat to the ISS,[184][185] and Birds-1 payloads. This mission launched for the first time a refurbished Dragon capsule,[186] serial number C106, which had flown in September 2014, on the SpaceX CRS-4 mission,[179] and was the first time since 2011, a reused spacecraft arrived at the ISS.[187] Five cubesats were included in the payload, the first satellites from the countries of Bangladesh (BRAC Onnesha), Ghana (GhanaSat-1), and Mongolia (Mazaalai).[188] | |||||||||

| 36 | 23 June 2017 19:10 |

F9 FT B1029.2[189] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | BulgariaSat-1[190] | 3,669 kg (8,089 lb)[191] | GTO | Bulsatcom | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| Second time a booster was reused, as B1029 had flown the Iridium mission in January 2017.[189] This was the first commercial Bulgarian-owned communications satellite.[189] | |||||||||

| 37 | 25 June 2017 20:25 |

F9 FT B1036.1[192] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | Iridium NEXT-2 (10 satellites) |

9,600 kg (21,200 lb) | LEO | Iridium Communications | Success | Success (JRTI) |

| Second Iridium constellation launch of 10 satellites, and first flight using titanium (instead of aluminium) grid fins to improve control authority and better cope with heat during re-entry.[193] | |||||||||

| 38 | 5 July 2017 23:38 |

F9 FT B1037.1[194] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | Intelsat 35e[195] | 6,761 kg (14,905 lb)[196] | GTO | Intelsat | Success | No attempt [159] |

| Originally expected to be flown on a Falcon Heavy,[197] improvements to the Merlin engines meant that the heavy satellite could be flown to GTO in an expendable configuration of Falcon 9.[198] The rocket achieved a supersynchronous orbit peaking at 43,000 km (27,000 mi), exceeding the minimum requirements of 28,000 km (17,000 mi).[199] Intelsat 35e is the largest Intelsat's currently active satellite.[200] | |||||||||

| 39 | 14 August 2017 16:31 |

F9 B4 B1039.1[201] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | SpaceX CRS-12[136] (Dragon C113.1) |

3,310 kg (7,300 lb) (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Success (LZ‑1) |

| Dragon carried 2,349 kg (5,179 lb) of pressurized and 961 kg (2,119 lb) unpressurized mass, including the Cosmic Ray Energetics and Mass Experiment (CREAM) detector.[184] First flight of the upgrade known informally as "Block 4", which increases thrust from the main engines and includes other small upgrades,[201] and last flight of a newly built Dragon capsule, as further missions are planned to use refurbished spacecraft.[202] Also launched the Educational Launch of Nanosatellites ELaNa 22 mission.[46] | |||||||||

| 40 | 24 August 2017 18:51 |

F9 FT B1038.1[203] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | Formosat-5[204][205] | 475 kg (1,047 lb)[206] | SSO | NSPO | Success | Success (JRTI) |

| First Earth observation satellite developed and constructed by Taiwan. The payload was much under the rocket's specifications, as the Spaceflight Industries SHERPA space tug had been removed from the cargo manifest of this mission,[207] leading to analyst speculations that with discounts due to delays, SpaceX lost money on the launch.[208] | |||||||||

| 41 | 7 September 2017 14:00[209] |

F9 B4 B1040.1[105] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | Boeing X-37B OTV-5 | 4,990 kg (11,000 lb)[210] + OTV payload |

LEO | USAF | Success | Success (LZ‑1) |

| Due to the classified nature of the mission, the second-stage speed and altitude telemetry were omitted from the launch webcast. It was the third flight of second X-37B. It was fastest turnaround of a X-37B by 2nd X-37B at 123 days. Notably, the primary contractor, Boeing, had launched the X-37B with ULA, a Boeing partnership and a SpaceX competitor.[211] Second flight of the Falcon 9 Block 4 upgrade.[212] | |||||||||

| 42 | 9 October 2017 12:37 |

F9 B4 B1041.1[213] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | Iridium NEXT-3 (10 satellites)[147] |

9,600 kg (21,200 lb) | Polar LEO | Iridium Communications | Success | Success (JRTI) |

| Third flight of the Falcon 9 Block 4 upgrade, and the third launch of 10 Iridium NEXT satellites.[213] | |||||||||

| 43 | 11 October 2017 22:53:00 |

F9 FT B1031.2[214] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | SES-11 / EchoStar 105 | 5,400 kg (11,900 lb)[215][216] | GTO | Success | Success (OCISLY) | |

| Third reuse and recovery of a previously flown first-stage booster, and the second time the contractor SES used a reflown booster.[214] The large satellite is shared, in "CondoSat" arrangement between SES and EchoStar.[217] | |||||||||

| 44 | 30 October 2017 19:34 |

F9 B4 B1042.1[213] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | Koreasat 5A[218] | 3,500 kg (7,700 lb) | GTO | KT Corporation | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| First SpaceX launch of a South Korean satellite, placed in GEO at 113.0° east.[219] It was the third launch and land for SpaceX in three weeks, and the 15th successful landing in a row.[220] A small fire was observed under the booster after it landed, leading to speculations about damages to the engines which would preclude it from flying it again.[221] | |||||||||

| 45 | 15 December 2017 15:36[222] |

F9 FT B1035.2[223] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-13[136] (Dragon C108.2) |

2,205 kg (4,861 lb) (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Success (LZ‑1) |

| First launch to take place at the refurbished pad at Cape Canaveral after the 2016, AMOS-6 explosion, and the 20th successful booster landing. Being the second reuse of a Dragon capsule (previously flown on SpaceX CRS-6) and fourth reuse of a booster (previously flown on SpaceX CRS-11) it was the first time both major components were reused on the same flight.[224][223] | |||||||||

| 46 | 23 December 2017 01:27[225] |

F9 FT B1036.2[223] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | Iridium NEXT-4 (10 satellites)[147] |

9,600 kg (21,200 lb) | Polar LEO | Iridium Communications | Success[226] | Controlled (ocean)[b] |

| In order to avoid delays and convinced of no increased risks, Iridium Communications accepted the use of a recovered booster for its 10 satellites, and became the first customer to fly the same first-stage booster twice (from the second Iridium NEXT mission).[227][228] SpaceX chose not to attempt recovery of the booster, but did perform a soft ocean touchdown.[229] | |||||||||

2018

editIn November 2017, Gwynne Shotwell expected to increase launch cadence in 2018, by about 50% compared to 2017, leveling out at a rate of about 30 to 40 per year, not including launches for the planned SpaceX satellite constellation Starlink.[230] The actual launch rate increased by 17% from 18 in 2017, to 21 in 2018, giving SpaceX the second most launches for the year for a rocket family, behind China's Long March.[231] Falcon Heavy made its first flight.

2018 was the first year when more flights were flown using reused boosters (13) than new boosters (ten).

Flight No. |

Date and time (UTC) |

Version, booster[a] |

Launch site |

Payload[c] | Payload mass | Orbit | Customer | Launch outcome |

Booster landing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47 | 8 January 2018 01:00[232] |

F9 B4 B1043.1 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Zuma[233] | Classified | LEO | Unspecified U.S. government agency | Success[234] | Success (LZ‑1) |

| The mission had been postponed by nearly two months. Following a nominal launch, the recovery of the first-stage booster marked the 17th successful recovery in a row.[235] Rumors appeared that the payload was lost, as the satellite might have failed to separate from the second stage due to a fault in the Northrop Grumman-manufactured payload adapter, to which SpaceX announced that their rocket performed nominally.[236] The classified nature of the mission means that there is little confirmed information. (more details) | |||||||||

| 48 | 31 January 2018 21:25[237] |

F9 FT B1032.2[238] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | GovSat-1 (SES-16)[239] | 4,230 kg (9,330 lb)[240] | GTO | SES | Success[241] | Controlled (ocean)[b] |

| Reused booster from the classified NROL-76 mission in May 2017.[238] Following a successful experimental soft ocean landing that used three engines, the booster unexpectedly remained intact. Despite initial talk about a potential recovery effort, the decision was instead made to intentionally destroy and sink the booster.[242] GovSat-1 satellite was put into a high-energy Supersynchronous Transfer Orbit of 250 km × 51,500 km (160 mi × 32,000 mi).[243][244] | |||||||||

| FH 1 | 6 February 2018 20:45[245] |

Falcon Heavy B1033 (core) |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | Elon Musk's Tesla Roadster[246][247] | ~1,250 kg (2,760 lb) | Heliocentric 0.99–1.67 AU[248] (close to Mars transfer orbit) |

SpaceX | Success | Failure (OCISLY) |

| B1023.2 (side) | Success (LZ‑1) | ||||||||

| B1025.2 (side) | Success (LZ‑2) | ||||||||

| Maiden flight of Falcon Heavy, using two recovered Falcon 9 cores as side boosters (from the Thaicom 8[249] and SpaceX CRS-9[125] missions), as well as a modified Block 3 booster reinforced to endure the additional load from the two side boosters. The static fire test, held on 24 January 2018, was the first time 27 engines were tested together.[250] The launch was a success, and the side boosters landed simultaneously at adjacent ground pads.[251] This was the first ever use of SpaceX Landing Zone 2. Drone ship landing of the central core failed due to TEA–TEB chemical igniter running out, preventing two of its engines from restarting; the landing failure caused damage to the nearby drone ship.[252][253] Final burn to heliocentric Earth-Mars orbit was performed after the second stage and payload cruised for 6 hours through the Van Allen radiation belts.[254] Later, Elon Musk tweeted that the third burn was successful,[255] and JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System showed the second stage and payload in an orbit with an aphelion of 1.67 AU.[256] The live webcast proved immensely popular, as it became the second most watched livestream so far on YouTube, reaching over 2.3 million concurrent views.[257] Over 100,000 visitors are believed to have come to the Space Coast to watch the launch in person.[258](more details) | |||||||||

| 49 | 22 February 2018 14:17[259] |

F9 FT B1038.2[260] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | Paz | 2,150 kg (4,740 lb) | SSO | Success | No attempt | |

| Starlink (Tintin A & B) | SpaceX | ||||||||

| Last flight of a Block 3 first stage. Reused the booster from the Formosat-5 mission.[260] Paz (peace) is Spain's first spy satellite[261] that will be operated in a constellation with the German SAR fleet TSX and TDX.[262] In addition, the rocket carried two SpaceX test satellites for their forthcoming communications network in low Earth orbit.[263][264] This core flew without landing legs and was expended at sea.[263] It also featured an upgraded payload fairing 2.0 with a first recovery attempt using the Mr. Steven crew boat equipped with a net. The fairing narrowly missed the boat, but achieved a soft water landing.[265][266][267] | |||||||||

| 50 | 6 March 2018 05:33[268] |

F9 B4 B1044.1[105] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 |

|

6,092 kg (13,431 lb)[271] | GTO | Success[272] | Controlled (ocean)[b] | |

| The Spanish commsat was the largest satellite yet flown by SpaceX, "nearly the size of a bus".[273] A drone ship landing was planned, but scrapped due to unfavorable weather conditions. After stage separation, the first stage booster successfully conducted an ocean landing in the Atlantic Ocean.[274] SpaceX left the landing legs and titanium grid fins in place to prevent further delays, after previous concerns with the fairing pressurization and conflicts with the Atlas V launch of GOES-S.[275] The Hispasat 30W-6 satellite was propelled into a supersynchronous transfer orbit.[276] | |||||||||

| 51 | 30 March 2018 14:14[277] |

F9 B4 B1041.2[260] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | Iridium NEXT-5 (10 satellites)[147] |

9,600 kg (21,200 lb) | Polar LEO | Iridium Communications | Success[278] | No attempt |

| Fifth Iridium NEXT mission launch of 10 satellites used the refurbished booster from third Iridium flight. As with recent reflown boosters, SpaceX used the controlled descent of the first stage to test more booster recovery options.[279][280] SpaceX planned a second recovery attempt of one half of the fairing using the specially modified boat Mr. Steven,[281] but the parafoil twisted, which led to the fairing half missing the boat.[282] | |||||||||

| 52 | 2 April 2018 20:30[283] |

F9 B4 B1039.2[284] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-14[136] (Dragon C110.2) |

2,647 kg (5,836 lb)[284] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success[285] | No attempt |

| The launch used a refurbished booster (from CRS-12) and a refurbished capsule (C110 from CRS-8).[284] External payloads include a materials research platform Materials International Space Station Experiment (MISSE-FF)[286] phase 3 of the Robotic Refueling Mission (RRM)[287] TSIS,[288] ASIM heliophysics sensor,[184] several crystallization experiments,[289] and the RemoveDEBRIS system aimed at space debris removal.[290] The booster was expended, and SpaceX collected more data on reentry profiles.[291][292] It also carried the first Costa Rican satellite, Project Irazú,[293] and the first Kenyan satellite, 1KUNS-PF.[294] | |||||||||

| 53 | 18 April 2018 22:51[295] |

F9 B4 B1045.1[260] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS)[296] | 362 kg (798 lb)[297] | HEO for P/2 orbit | NASA (LSP) | Success[298] | Success (OCISLY) |

| First NASA high-priority science mission launched by SpaceX. Part of the Explorers program, TESS is space telescope intended for wide-field search of exoplanets transiting nearby stars. It was the first time SpaceX launched a scientific satellite which wasn't designed to focus on Earth observations. The second stage placed the spacecraft into a high elliptical Earth orbit, after which the satellite performed its own maneuvers, including a lunar flyby, such that over the course of two months it reached a stable 2:1 resonant orbit with the Moon.[299] In January 2018, SpaceX received NASA's Launch Services Program Category 2 certification of its Falcon 9 "Full Thrust", certification which is required for launching "medium-risk" missions like TESS.[300] Last launch of a new Block 4 booster,[301] and the 24th successful recovery of the first stage. An experimental water landing of the launch fairing was performed in order to attempt fairing recovery, primarily as a test of parachute systems.[297][298] | |||||||||

| 54 | 11 May 2018 20:14[302] |

F9 B5[303] B1046.1[260] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | Bangabandhu-1[304][305] | 3,600 kg (7,900 lb)[306] | GTO | Thales-Alenia / BTRC | Success[307] | Success (OCISLY) |

| First Block 5 launch vehicle booster to fly. Initially planned for an Ariane 5 launch in December 2017,[308] it became the first Bangladeshi commercial satellite,[309] BRAC Onnesha is a cubesat built by Thales Alenia Space.[310][311] It is intended to serve telecom services from 119.0° east with a lifetime of 15 years.[312] It was the 25th successfully recovered first stage booster.[307] | |||||||||

| 55 | 22 May 2018 19:47[313] |

F9 B4 B1043.2[314] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | 6,460 kg (14,240 lb)[e] | Polar LEO | Success[319] | No attempt | ||

| Sixth Iridium NEXT mission launching 5 satellites used the refurbished booster from Zuma. GFZ arranged a rideshare of GRACE-FO on a Falcon 9 with Iridium following the cancellation of their Dnepr launch contract in 2015.[315] Iridium CEO Matt Desch disclosed in September 2017, that GRACE-FO would be launched on this mission.[320] The booster reuse turnaround was a record 4.5 months between flights.[321] | |||||||||

| 56 | 4 June 2018 04:45[322] |

F9 B4 B1040.2[260] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SES-12[323] | 5,384 kg (11,870 lb)[324] | GTO | SES | Success[325] | No attempt |

| The communications satellite serving the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific region at the same place as SES-8, and was the largest satellite built for SES.[323] The Block 4 first stage was expended,[324] while the second stage was a Block 5 version, delivering more power towards a higher supersynchronous transfer orbit with 58,000 km (36,000 mi) apogee.[326] | |||||||||

| 57 | 29 June 2018 09:42[327] |

F9 B4 B1045.2[328] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-15 (Dragon C111.2) |

2,697 kg (5,946 lb)[329] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success[330] | No attempt |

| Payload included MISSE-FF 2, ECOSTRESS, a Latching End Effector, and Birds-2 payloads. The refurbished booster featured a record 2.5 months period turnaround from its original launch of TESS, a record held until February 2020, with the Starlink L4 mission. The fastest previous was 4.5 months. This was the last flight of a Block 4 booster, which was expended into the Atlantic Ocean without landing legs and grid fins.[331] | |||||||||

| 58 | 22 July 2018 05:50[332] |

F9 B5 B1047.1 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Telstar 19V[333] | 7,075 kg (15,598 lb)[334] | GTO[335] | Telesat | Success[336] | Success (OCISLY) |

| SSL-manufactured communications satellite intended to be placed at 63.0° west over the Americas,[337] replacing Telstar 14R.[335] At 7,075 kg (15,598 lb), it became the heaviest commercial communications satellite so far launched.[338][339] This necessitated that the satellite be launched into a lower-energy orbit than a usual GTO, with its initial apogee at roughly 17,900 km (11,100 mi).[335] | |||||||||

| 59 | 25 July 2018 11:39[340] |

F9 B5[341] B1048.1[342] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | Iridium NEXT-7 (10 satellites)[147] |

9,600 kg (21,200 lb) | Polar LEO | Iridium Communications | Success | Success (JRTI) |

| Seventh Iridium NEXT launch, with 10 communication satellites. The booster landed safely on the drone ship in the worst weather conditions for any landing yet attempted. Mr. Steven boat with an upgraded 4x size net was used to attempt fairing recovery but failed due to harsh weather.[343][344] | |||||||||

| 60 | 7 August 2018 05:18[345] |

F9 B5 B1046.2[346] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Merah Putih (formerly Telkom-4)[347][348] | 5,800 kg (12,800 lb)[349] | GTO | Telkom Indonesia | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| Indonesian comsat intended to replace the aging Telkom-1 at 108.0° East.[350] First reflight of a Block 5-version booster.[351] | |||||||||

| 61 | 10 September 2018 04:45[352] |

F9 B5 B1049.1[260] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Telstar 18V / Apstar-5C[333] | 7,060 kg (15,560 lb)[352] | GTO[352] | Telesat | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| Condosat for 138.0° East over Asia and Pacific.[353] Delivered to a GTO orbit with apogee close to 18,000 km (11,000 mi).[352] | |||||||||

| 62 | 8 October 2018 02:22[354] |

F9 B5 B1048.2[355] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | SAOCOM 1A[356][357] | 3,000 kg (6,600 lb)[354] | SSO | CONAE | Success | Success (LZ‑4) |

| Argentinian Earth-observation satellite was originally intended to be launched in 2012.[356] First landing on the West Coast ground pad called SpaceX Landing Zone 4.[354] | |||||||||

| 63 | 15 November 2018 20:46[358] |

F9 B5 B1047.2[260] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | Es'hail 2[359] | 5,300 kg (11,700 lb)[360] | GTO | Es'hailSat | Success[361] | Success (OCISLY) |

| Qatari comsat positioned at 26.0° east.[359] This launch used redesigned COPVs. This was to meet NASA safety requirements for commercial crew missions, in response to the September 2016, pad explosion.[362] | |||||||||

| 64 | 3 December 2018 18:34:05 |

F9 B5 B1046.3[260] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | SSO-A (SmallSat Express) (SHERPA) |

~4,000 kg (8,800 lb)[363] | SSO | Spaceflight Industries | Success[364] | Success (JRTI) |

| Rideshare mission[365] where two SHERPA dispensers deployed 64 small satellites,[366][367] including Eu:CROPIS[368] for the German DLR, HIBER-2 for the Dutch Hiber Global,[369] ITASAT-1 for the Brazilian Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica,[370] two high-resolution SkySat imaging satellites for Planet Labs,[371] and two high school CubeSats part of NASA's ELaNa 24.[372] This was the first time a booster was used for a third flight. | |||||||||

| 65 | 5 December 2018 18:16 |

F9 B5 B1050[260] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-16 (Dragon C112.2) |

2,500 kg (5,500 lb)[373] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Failure (LZ‑1) |

| First CRS mission with the Falcon 9 Block 5. This carried the Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation lidar (GEDI) as an external payload.[374] The mission was delayed by one day due to moldy rodent food for one of the experiments on the Space Station. A previously flown Dragon spacecraft was used for the mission. The booster, in use for the first time, experienced a grid fin hydraulic pump stall on reentry, which caused it to spin out of control and touchdown at sea, heavily damaging the interstage section; this was the first failed landing targeted for a ground pad.[375][376] | |||||||||

| 66 | 23 December 2018 13:51[377] |

F9 B5 B1054[378] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | GPS III-01 (Vespucci) | 4,400 kg (9,700 lb)[379] | MEO | USAF | Success | No attempt |

| Initially planned for a Delta IV launch,[380] this was SpaceX's first launch of an EELV-class payload.[381] There was no attempt to recover the first-stage booster for reuse[382][378] due to the customer's requirements, including a high inclination orbit of 55.0°.[383] Nicknamed Vespucci, the USAF marked the satellite operational on 1 January 2020, under the label SVN 74.[384] | |||||||||

2019

editShotwell stated in May 2019, that SpaceX might conduct up to 21 launches in 2019, not counting Starlink missions.[385] However, with a slump in worldwide commercial launch contracts in 2019, SpaceX ended up launching only 13 times throughout 2019 (eleven without Starlink), significantly fewer than in 2017, and 2018, and third most launches of vehicle class behind China's Long March and Russia's Soyuz launch vehicles.[386]

In 2019, SpaceX continued the trend of operating more flights with reused boosters (ten) than new boosters (seven).

Flight No. |

Date and time (UTC) |

Version, booster[a] |

Launch site |

Payload[c] | Payload mass | Orbit | Customer | Launch outcome |

Booster landing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 67 | 11 January 2019 15:31[387] |

F9 B5 B1049.2[388] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | Iridium NEXT-8 (10 satellites)[147] |

9,600 kg (21,200 lb) | Polar LEO | Iridium Communications | Success | Success (JRTI) |

| Final launch of the Iridium NEXT contract, launching 10 satellites. | |||||||||

| 68 | 22 February 2019 01:45[389] |

F9 B5 B1048.3[390] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 |

|

4,850 kg (10,690 lb)[394] | GTO | Success | Success (OCISLY) | |

| Nusantara Satu is a private Indonesian comsat planned to be located at 146.0° east,[391] with a launch mass of 4,100 kg (9,000 lb),[394] and featuring electric propulsion for orbit-raising and station-keeping.[395][396] S5, a 60-kg smallsat by the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), was piggybacked on Nusantara Satu, and was deployed near its GEO position to perform a classified space situational awareness mission. This launch opportunity was brokered by Spaceflight Industries as "GTO-1".[393]

The Beresheet Moon lander (initially called Sparrow) was one of the candidates for the Google Lunar X-Prize, whose developers SpaceIL had secured a launch contract with Spaceflight Industries in October 2015.[397] Its launch mass was 585 kg (1,290 lb) including fuel.[398] After separating into a supersynchronous transfer orbit[399] with an apogee of 69,400 km (43,100 mi),[400][398] Beresheet raised its orbit by its own power over two months and flew to the Moon.[399][401] After successfully getting into lunar orbit, Beresheet attempted to land on the Moon on 11 April 2019, but failed.[402] | |||||||||

| 69 | 2 March 2019 07:49[403] |

F9 B5 B1051.1[260][404] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | Crew Dragon Demo-1[405] (Dragon C204) |

12,055 kg (26,577 lb)[406][f] | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CCD) | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| First flight of the SpaceX Crew Dragon. This was the first demonstration flight for the NASA Commercial Crew Program which awarded SpaceX a contract in September 2014, with flights hoped as early as 2015.[407] The Dragon performed an autonomous docking to the ISS 27 hours after launch with the hatch being opened roughly 2 hours later.[408] The vehicle spent nearly a week docked to the ISS to test critical functions. It undocked roughly a week later on 8 March 2019, and splashed down six hours later at 13:45.[409] The Dragon used on this flight was scheduled to fly on the inflight abort test in mid-2019, but was destroyed during testing.[410] The booster B1051.1 replaced B1050[411] and flew again on 12 June 2019. | |||||||||

| FH 2 | 11 April 2019 22:35[412] |

FH B5 B1055 (core) |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | Arabsat-6A[413] | 6,465 kg (14,253 lb)[414] | GTO | Arabsat | Success | Partial failure[g] (OCISLY) |

| B1052.1 (side) | Success (LZ‑1) | ||||||||

| B1053.1 (side) | Success (LZ‑2) | ||||||||

| Second flight of Falcon Heavy, the first commercial flight, and the first one using Block 5 boosters. SpaceX successfully landed the side boosters at Landing Zone 1 and LZ 2 and reused the side boosters later for the STP-2 mission. The central core landed on drone ship Of Course I Still Love You, located 967 km (601 mi) downrange, the furthest successful sea landing so far.[416] Despite the initially successful landing, due to rough seas and the fact that the Octagrabber had not been configured to grab the central core of a Falcon Heavy, the central core was unable to be secured to the deck for recovery and later tipped overboard in transit. SpaceX has since developed new attachment fixtures for the Octagrabber so this problem won't happen again.[417][418] SpaceX recovered the fairing from this launch and later reused it in the November 2019, Starlink launch.[419][420] Arabsat-6A, a 6,465 kg (14,253 lb) Saudi satellite, is the most advanced commercial communications satellite so far built by Lockheed Martin.[421] The Falcon Heavy delivered the Arabsat-6A into a supersynchronous transfer orbit with 90,000 km (56,000 mi) apogee with an inclination of 23.0° to the equator.[422] | |||||||||

| 70 | 4 May 2019 06:48 |

F9 B5 B1056.1[411] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-17[136] (Dragon C113.2) |

2,495 kg (5,501 lb)[423] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| A Commercial Resupply Service mission to the International Space Station carrying nearly 2.5 tons of cargo including the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-3 as an external payload.[423] Originally planned to land at Landing Zone 1, the landing was moved to the drone ship after a Dragon 2 had an anomaly during testing at LZ-1.[424] | |||||||||

| 71 | 24 May 2019 02:30 |

F9 B5 B1049.2[425] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Starlink: v0.9 launch (60 satellites) | 13,620 kg (30,030 lb)[426] | LEO | SpaceX | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| Following the launch of the two Tintin test satellites, this was the first full-scale test launch of the Starlink constellation, launching 60 v0.9 "production design" satellites.[427][428][429] Each Starlink satellite has a mass of 227 kg (500 lb),[430] and the combined launch mass was 13,620 kg (30,030 lb) the heaviest payload launched by SpaceX at that time.[431] The fairings were recovered[432] and reused for Starlink L5 in March 2020.[433] These are the first commercial satellites to use krypton as fuel for their ion thrusters, which is cheaper than the usual xenon fuel.[434] | |||||||||

| 72 | 12 June 2019 14:17 |

F9 B5 B1051.2[411] |

Vandenberg, SLC‑4E | RADARSAT Constellation (3 satellites) |

4,200 kg (9,300 lb)[435] | SSO | Canadian Space Agency (CSA) | Success | Success (LZ‑4) |

| A trio of satellites built for Canada's RADARSAT program were launched that plan to replace the aging Radarsat-1 and Radarsat-2. The new satellites contain Automated Identification System (AIS) for locating ships and provide the world's most advanced, comprehensive method of maintaining Arctic sovereignty, conducting coastal surveillance, and ensuring maritime security.[436][435] The mission was originally scheduled to lift off in February but due to the landing failure of booster B1050, this flight was switched to B1051 (used on Crew Dragon Demo-1) and delayed to allow refurbishment and transport to the West coast.[411] The booster landed safely through fog.[437] A payload cost of $706 million CAD[438] (around US$550 million) made this one of SpaceX's most expensive payloads launched at that time.[439] | |||||||||

| FH 3 | 25 June 2019 06:30[440] |

Falcon Heavy B5 B1057 (core)[411] |

Kennedy, LC‑39A | Space Test Program Flight 2 (STP-2) | 3,700 kg (8,200 lb) | LEO / MEO | USAF | Success | Failure (OCISLY) |

| B1052.2 (side) | Success (LZ‑2) | ||||||||

| B1053.2 (side) | Success (LZ‑1) | ||||||||

| USAF Space Test Program Flight 2 (STP-2)[71] carried 24 small satellites,[441] including: FormoSat-7 A/B/C/D/E/F integrated using EELV Secondary Payload Adapter,[442] DSX, Prox-1[443] GPIM,[444] DSAC,[445] ISAT, SET,[446] COSMIC-2, Oculus-ASR, OBT, NPSat,[447] and several CubeSats including E-TBEx,[448] LightSail 2,[449] TEPCE, PSAT, and three ELaNa 15 CubeSats. Total payload mass was 3,700 kg (8,200 lb).[450] The mission lasted six hours during which the second stage ignited four times and went into different orbits to deploy satellites including a "propulsive passivation maneuver".[447][451]

Third flight of Falcon Heavy. The side boosters from the Arabsat-6A mission just 2.5 months before were reused on this flight and successfully returned to LZ-1 and LZ-2.[411] The center core, in use for the first time, underwent the most energetic reentry attempted by SpaceX, and attempted a landing over 1,200 km (750 mi) downrange, 30% further than any previous landing.[452] This core suffered a thrust vector control failure in the center engine caused by a breach in the engine bay due to the extreme heat. The core thus failed its landing attempt on the drone ship Of Course I Still Love You due to lack of control when the outer engines shut down.[453] For the first time, one fairing half was successfully landed on the catch-net of the support ship GO Ms. Tree (formerly Mr. Steven).[454] | |||||||||

| 73 | 25 July 2019 22:01[455] |

F9 B5 B1056.2[456] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-18[136] (Dragon C108.3) |

2,268 kg (5,000 lb)[455] (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Success (LZ‑1) |

| This launch carried nearly 9,000 individual unique payloads including over one ton of science experiments, the most so far launched on a SpaceX Dragon. The third International Docking Adapter (IDA-3), a replacement for the first IDA lost during the CRS-7 launch anomaly, was one of the external payloads on this mission.[457] Along with food and science, the Dragon also carried the ELaNa 27 RFTSat CubeSat[458] and MakerSat-1 which will be used to demonstrate microgravity additive manufacturing. The satellite is expected to be launched by a Cygnus dispenser later in July 2019.

The booster used on this flight was the same used on CRS-17 earlier in the year; originally, it was planned to reuse it again for the CRS-19 mission later this year,[459] but the plan was scrapped. For the first time, the twice flown Dragon spacecraft also made a third flight.[460] Also used for the first time was a gray-band painted where the RP-1 kerosene tank is located, known as Falcon long coast mission-extension kit, to help with thermal conductivity and thus saving fuel during long coasts.[461] | |||||||||

| 74 | 6 August 2019 23:23[462] |

F9 B5 B1047.2[463] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | AMOS-17[464] | 6,500 kg (14,300 lb)[465] | GTO | Spacecom | Success | No attempt |

| AMOS-17 is the most advanced high-throughput satellite to provide satellite communication services to Africa.[466] Following the loss of AMOS-6 in September 2016, Spacecom was granted a free launch in compensation for the lost satellite.[467] Due to the free launch, Spacecom was able to expend the booster with no extra cost that comes with expending a booster, and thus could reach final orbit quicker. This booster became the second Block 5 booster to be expended.[465][468] For the second time, Ms. Tree managed to catch a fairing half directly into its net.[469] | |||||||||

| 75 | 11 November 2019 14:56[470] |

F9 B5 B1048.4 |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | Starlink: Launch 1 (60 satellites) | 15,600 kg (34,400 lb)[426] | LEO | SpaceX | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| First launch of 60 Starlink v1 satellites to a 290 km (180 mi) orbit at an inclination of 53°. Second large batch of Starlink satellites and the first operational mission to deploy the internet constellation. At 15,600 kg (34,400 lb), it is the heaviest payload so far launched by SpaceX, breaking the record set by the Starlink v0.9 flight earlier that year.[426] This flight marked the first time that a Falcon 9 booster made a fourth flight and landing.[471] This was also the first time that a Falcon 9 re-used fairings (from ArabSat-6A in April 2019).[420] It was planned to recover the fairings with both Ms. Tree and Ms. Chief but the plan was abandoned due to rough seas.[426] | |||||||||

| 76 | 5 December 2019 17:29[472] |

F9 B5 B1059.1[473] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | SpaceX CRS-19[474] (Dragon C106.3) |

2,617 kg (5,769 lb) (excl. Dragon mass) | LEO (ISS) | NASA (CRS) | Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| Second re-supply flight to use a Cargo Dragon for the third time.[475] This flight carried Robotic Tool Stowage (RiTS), a docking station that allows equipment that looks for leaks on the Space Station be stored on the outside. Also on board were upgrades for the Cold Atom Laboratory (CAL). Onboard experiments include the testing of the spread of fire in space, mating barley in microgravity and experiments to test muscle and bone growth in microgravity.[476] Secondary payloads include the Hyperspectral Imager Suite (HISUI), an experiment to image high resolution across all colours of the light spectrum, allowing for imaging of soil, rocks, vegetation, snow, ice and man-made objects. Additionally, there were three CubeSats from NASA's ELaNa 28 mission,[372] including the AztechSat-1 satellite built by students in Mexico.[476] | |||||||||

| 77 | 17 December 2019 00:10[477] |

F9 B5 B1056.2[473] |

Cape Canaveral, SLC‑40 | JCSat-18 / Kacific 1[478] | 6,956 kg (15,335 lb)[477] | GTO | Sky Perfect JSAT Kacific 1 |

Success | Success (OCISLY) |

| Singaporean-Japanese CondoSat that will cover the Asia-Pacific region.[479] Due to the heavy weight of the payload, it was injected into a lower energy sub-synchronous orbit of 20,000 km (12,000 mi); the satellite itself will transfer to full GTO. This was the third Falcon 9 launch for JSAT and the previous two were in 2016. SpaceX successfully landed B1056.3 but both fairing halves missed the recovery boats Ms. Tree and Ms. Chief.[480] | |||||||||

Notable launches

editFirst flight of Falcon 9

editOn 4 June 2010, the first Falcon 9 launch successfully placed a test payload into the intended orbit.[4] Starting at the moment of liftoff, the booster experienced roll.[481] The roll stopped before the craft reached the top of the tower, but the second stage began to roll near the end of its burn,[4] tumbling out of control during the passivation process and creating a gaseous halo of vented propellant that could be seen from all of Eastern Australia, raising UFO concerns.[482][483]

COTS demonstration flights

editSecond launch of Falcon 9 was COTS Demo Flight 1, which placed an operational Dragon capsule in a roughly 300 km (190 mi) orbit on 8 December 2010,[484] The capsule re-entered the atmosphere after two orbits, allowing testing for the pressure vessel integrity, attitude control using the Draco thrusters, telemetry, guidance, navigation, control systems, and the PICA-X heat shield, and intended to test the parachutes at speed. The capsule was recovered off the coast of Mexico[485] and then placed on display at SpaceX headquarters.[486]

The remaining objectives of the NASA COTS qualification program were combined into a single Dragon C2+ mission,[487] on the condition that all milestones would be validated in space before berthing Dragon to the ISS. The Dragon capsule was propelled to orbit on 22 May, and for the next days tested its positioning system, solar panels, grapple fixture, proximity navigation sensors, and its rendezvous capabilities at safe distances. After a final hold position at 9 m (30 ft) away from the Harmony docking port on 25 May, it was grabbed with the station's robotic arm (Canadarm2), and eventually, the hatch was opened on 26 May. It was released on 31 May and successfully completed all the return procedures,[488] and the recovered Dragon C2+ capsule is now on display at Kennedy Space Center.[489] Falcon 9 and Dragon thus became the first fully commercially developed launcher to deliver a payload to the International Space Station, paving the way for SpaceX and NASA to sign the first Commercial Resupply Services agreement for 12 cargo deliveries.[490]

CRS-1

editFirst operational cargo resupply mission to ISS, the fourth flight of Falcon 9, was launched on 7 October 2012. At 76 seconds after liftoff, engine 1 of the first stage suffered a loss of pressure which caused an automatic shutdown of that engine, but the remaining eight first-stage engines continued to burn and the Dragon capsule reached orbit successfully and thus demonstrated the rocket's "engine out" capability in flight.[491][492] Due to ISS visiting vehicle safety rules, at NASA's request, the secondary payload Orbcomm-2 was released into a lower-than-intended orbit.[22] The mission continued to rendezvous and berth the Dragon capsule with the ISS where the ISS crew unloaded its payload and reloaded the spacecraft with cargo for return to Earth.[493] Despite the incident, Orbcomm said they gathered useful test data from the mission and planned to send more satellites via SpaceX,[21] which happened in July 2014, and December 2015.

Maiden flight of v1.1

editFollowing unsuccessful attempts at recovering the first stage with parachutes, SpaceX upgraded to much larger first stage booster and with greater thrust, termed Falcon 9 v1.1 (also termed Block 2[494]). SpaceX performed its first, demonstration flight of this version on 29 September 2013,[495] with CASSIOPE as a primary payload. This had a payload mass that is very small relative to the rocket's capability, and was launched at a discounted rate, approximately 20% of the normal published price.[496][497][26] After the second stage separation, SpaceX conducted a novel high-altitude, high-velocity flight test, wherein the booster attempted to reenter the lower atmosphere in a controlled manner and decelerate to a simulated over-water landing.[26]

Loss of CRS-7 mission

editOn 28 June 2015, Falcon 9 Flight 19 carried a Dragon capsule on the seventh Commercial Resupply Services mission to the ISS. The second stage disintegrated due to an internal helium tank failure while the first stage was still burning normally. This was the first (and only as of March 2024) primary mission loss during flight for any Falcon 9 rocket.[90] In addition to ISS consumables and experiments, this mission carried the first International Docking Adapter (IDA-1), whose loss delayed preparedness of the station's US Orbital Segment (USOS) for future crewed missions.[498]

Performance was nominal until T+140 seconds into launch when a cloud of white vapor appeared, followed by rapid loss of second-stage LOX tank pressure. The booster continued on its trajectory until complete vehicle breakup at T+150 seconds. The Dragon capsule was ejected from the disintegrating rocket and continued transmitting data until impact with the ocean. SpaceX officials stated that the capsule could have been recovered if the parachutes had deployed; however, the Dragon software did not include any provisions for parachute deployment in this situation.[92] Subsequent investigations traced the cause of the accident to the failure of a strut that secured a helium bottle inside the second-stage LOX tank. With the helium pressurization system integrity breached, excess helium quickly flooded the tank, eventually causing it to burst from overpressure.[499][500] NASA's independent accident investigation into the loss of SpaceX CRS-7 found that the failure of the strut which led to the breakup of the Falcon-9 represented a design error. Specifically, that industrial grade stainless steel had been used in a critical load path under cryogenic conditions and flight conditions, without additional part screening, and without regard to manufacturer recommendations.[501]

Full-thrust version and first booster landings

editAfter pausing launches for months, SpaceX launched on 22 December 2015, the highly anticipated return-to-flight mission after the loss of CRS-7. This launch inaugurated a new Falcon 9 Full Thrust version (also initially termed Block 3[494]) of its flagship rocket featuring increased performance, notably thanks to subcooling of the propellants. After launching a constellation of 11 Orbcomm-OG2 second-generation satellites,[502] the first stage performed a controlled-descent and landing test for the eighth time, SpaceX attempted to land the booster on land for the first time. It managed to return the first stage successfully to the Landing Zone 1 at Cape Canaveral, marking the first successful recovery of a rocket first stage that launched a payload to orbit.[503] After recovery, the first stage booster performed further ground tests and then was put on permanent display outside SpaceX's headquarters in Hawthorne, California.[99]

On 8 April 2016, SpaceX delivered its commercial resupply mission to the International Space Station marking the return-to-flight of the Dragon capsule, after the loss of CRS-7. After separation, the first-stage booster slowed itself with a boostback maneuver, re-entered the atmosphere, executed an automated controlled descent and landed vertically onto the drone ship Of Course I Still Love You, marking the first successful landing of a rocket on a ship at sea.[504] This was the fourth attempt to land on a drone ship, as part of the company's experimental controlled-descent and landing tests.[505]

Loss of AMOS-6 on the launch pad

editOn 1 September 2016, the 29th Falcon 9 rocket exploded on the launchpad while propellant was being loaded for a routine pre-launch static fire test. The payload, Israeli satellite AMOS-6, partly commissioned by Facebook, was destroyed with the launcher.[506] On 2 January 2017, SpaceX released an official statement indicating that the cause of the failure was a buckled liner in several of the COPV tanks, causing perforations that allowed liquid and/or solid oxygen to accumulate underneath the COPVs carbon strands, which were subsequently ignited possibly due to friction of breaking strands.[144]

Inaugural reuse of the first stage

editOn 30 March 2017, Flight 32 launched the SES-10 satellite with the first-stage booster B1021, which had been previously used for the CRS-8 mission a year earlier. The stage was successfully recovered a second time and was retired and put on display at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.[507]

Zuma launch controversy

editZuma was a classified United States government satellite and was developed and built by Northrop Grumman at an estimated cost of US$3.5 billion.[508] Its launch, originally planned for mid-November 2017, was postponed to 8 January 2018, as fairing tests for another SpaceX customer were assessed. Following a successful Falcon 9 launch, the first-stage booster landed at LZ-1.[235] Unconfirmed reports suggested that the Zuma spacecraft was lost,[236] with claims that either the payload failed following orbital release, or that the customer-provided adapter failed to release the satellite from the upper stage, while other claims argued that Zuma was in orbit and operating covertly.[236] SpaceX's COO Gwynne Shotwell stated that their Falcon 9 "did everything correctly" and that "Information published that is contrary to this statement is categorically false".[236] A preliminary report indicated that the payload adapter, modified by Northrop Grumman after purchasing it from a subcontractor, failed to separate the satellite from the second stage under the zero gravity conditions.[509][508] Due to the classified nature of the mission, no further official information is expected.[236]

Falcon Heavy test flight

editThe maiden launch of the Falcon Heavy occurred on 6 February 2018, marking the launch of the most powerful rocket since the Saturn V, with a theoretical payload capacity to low Earth orbit more than double the Delta IV Heavy.[510][511] Both side boosters landed nearly simultaneously after a ten-minute flight. The central core failed to land on a floating platform at sea.[253] The rocket carried a car and a mannequin to an eccentric heliocentric orbit that reaches further than the aphelion of Mars.[512]

Maiden flight Crew Dragon and first crewed flight

editOn 2 March 2019, SpaceX launched its first orbital flight of Dragon 2 (Crew Dragon). It was an uncrewed mission to the International Space Station. The Dragon contained a mannequin named Ripley which was equipped with multiple sensors to gather data about how a human would feel during the flight. Along with the mannequin was 300 pounds of cargo of food and other supplies.[513] Also on board was Earth plush toy referred to as a 'super high tech zero-g indicator'.[514] The toy became a hit with astronaut Anne McClain who showed the plushy on the ISS each day[515] and also deciding to keep it on board to experience the crewed SpX-DM2.

The Dragon spent six days in space including five docked to the International Space Station. During the time, various systems were tested to make sure the vehicle was ready for US astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken to fly in it in 2020. The Dragon undocked and performed a re-entry burn before splashing down on 8 March 2019, at 08:45 EST, 320 km (200 mi) off the coast of Florida.[516] SpaceX held a successful launch of the first commercial orbital human space flight on 30 May 2020, crewed with NASA astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken. Both astronauts focused on conducting tests on the Crew Dragon capsule. Crew Dragon successfully returned to Earth, splashing down in the Gulf of Mexico on 2 August 2020.[517]

Booster reflight records

editSpaceX has developed a program to reuse the first-stage booster, setting multiple booster reflight records:

- B1021 became, on 30 March 2017, the first booster to be successfully recovered a second time, on Flight 32 launching the SES-10 satellite. After that, it was retired and put on display at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.[507]

- On 3 December 2018, Spaceflight SSO-A launched on B1046. It was the first commercial mission to use a booster flying for the third time.

- B1048 was the first booster to be recovered four times on 11 November 2019.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Falcon 9 first-stage boosters have a four-digit serial number. A decimal point followed by a number indicates the flight count. For example, B1021.1 and B1021.2 represent the first and second flights of booster B1021. Boosters without a decimal point were expended on their first flight. Additionally, missions where boosters are making their first flight are shown with a mint-colored background.

- ^ a b c d e f g h A controlled "ocean landing" denotes a controlled atmospheric entry, descent and vertical splashdown on the ocean's surface at near zero velocity, for the sole purpose of gathering test data; such boosters were destroyed at sea.

- ^ a b c d e f Dragon spacecraft have a three-digit serial number. A decimal point followed by a number indicates the flight count. For example, C106.1 and C106.2 represent the first and second flights of Dragon C106.

- ^ Since it was destroyed in a pre-flight test, SpaceX does not count this as an attempted flight in their launch totals. Some sources consider this planned flight into the counting schemes, and as a result, some sources might list launch totals after 2016 with one additional launch.

- ^ Payload comprises five Iridium satellites weighing 860 kg each,[317] two GRACE-FO satellites weighing 580 kg each,[318] plus a 1000 kg dispenser.[153]

- ^ Total payload mass includes the Crew Dragon capsule, fuel, suited mannequin, instrumentation and 204 kg of cargo.

- ^ Despite making a successful landing, de-tanking and heading back home, the stage tipped over at sea. This is considered a partially failed landing as the stage was destroyed during transport.[415]

References

edit- ^ "SpaceX debuts new model of the Falcon 9 rocket designed for astronauts". Spaceflightnow.com. 11 May 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Clark, Stephen (18 May 2012). "Q&A with SpaceX founder and chief designer Elon Musk". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

The next version of Falcon 9 will be used for everything. The last flight of version 1.0 will be Flight 5. All future missions after Flight 5 will be v1.1.

- ^ a b c d e f "Space Launch Report: SpaceX Falcon 9 v1.2 Data Sheet". Space Launch Report. 14 August 2017. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c Clark, Stephen (4 June 2010). "Falcon 9 booster rockets into orbit on dramatic first launch". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Graham, William (30 March 2017). "SpaceX conducts historic Falcon 9 re-flight with SES-10 – Lands booster again". NASASpaceFlight.com.

- ^ a b Spencer, Henry (30 September 2011). "Falcon rockets to land on their toes". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (3 June 2010). "Falcon 9 demo launch will test more than a new rocket". SpaceFlight Now. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (9 December 2010). "Mission Status Center". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (7 December 2010). "SpaceX on the verge of unleashing Dragon in the sky". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Matt (7 May 2010). "Preparations for first Falcon 9 launch". Space Fellowship. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Krebs, Gunter D. "Dragon C1". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ Berger, Eric (3 June 2020). "Forget Dragon, the Falcon 9 rocket is the secret sauce of SpaceX's success". ArsTechnica. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ a b Amos, Jonathan (22 May 2012). "Nasa chief hails new era in space". BBC News. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Carreau, Mark (20 July 2011). "SpaceX Station Cargo Mission Eyes November Launch". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ Hartman, Dan (23 July 2012). "International Space Station Program Status" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 25 September 2017. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (22 May 2012). "Dragon circling Earth after flawless predawn blastoff". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Launch Log". Spaceflight Now. 1 February 2016. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "SpaceX Launch Manifest". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^

(secondary payload) de Selding, Peter B. (25 May 2012). "Orbcomm Eagerly Awaits Launch of New Satellite on Next Falcon 9". SpaceNews. Retrieved 28 May 2012. - ^ a b c Krebs, Gunter. "Orbcomm FM101, ..., FM119 (OG2)". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ a b Editorial (30 October 2012). "First Outing for SpaceX". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (11 October 2012). "Orbcomm craft falls to Earth, company claims total loss". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ de Selding, Peter B. (11 October 2012). "Orbcomm Craft Launched by Falcon 9 Falls out of Orbit". SpaceNews. Retrieved 12 October 2012.