Nils Olof Thorbjörn Fälldin (24 April 1926 – 23 July 2016) was a Swedish politician and farmer who served as the prime minister of Sweden from 1976 to 1978 and again from 1979 to 1982, heading three non-consecutive cabinets. He was the leader of the Swedish Centre Party from 1971 to 1985.[1]

Thorbjörn Fälldin | |

|---|---|

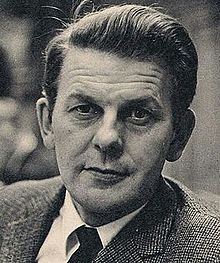

Thorbjörn Fälldin in 1967. | |

| Prime Minister of Sweden | |

| In office 12 October 1979 – 8 October 1982 | |

| Monarch | Carl XVI Gustaf |

| Deputy | |

| Preceded by | Ola Ullsten |

| Succeeded by | Olof Palme |

| In office 8 October 1976 – 18 October 1978 | |

| Monarch | Carl XVI Gustaf |

| Deputy | |

| Preceded by | Olof Palme |

| Succeeded by | Ola Ullsten |

| Leader of the Centre Party | |

| In office 21 June 1971 – 5 December 1985 | |

| Preceded by | Gunnar Hedlund |

| Succeeded by | Karin Söder (Acting) |

| Member of the Riksdag | |

| In office 1 January 1971 – 5 December 1985 | |

| Constituency | Västernorrland County |

| Member of the Second Chamber | |

| In office 1958–1971 | |

| Constituency | Västernorrland County |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nils Olof Thorbjörn Fälldin 24 April 1926 Högsjö, Sweden |

| Died | 23 July 2016 (aged 90) Ås, Sweden |

| Political party | Centre Party |

| Spouse |

Solveig Fälldin (m. 1956) |

On his first appointment in 1976, he was the first non-Social Democrat Prime Minister for 40 years and the first since the 1930s not to have worked as a professional politician since his teens.[2] He was also the last Prime Minister to not be from the Social Democrats or Moderate Party.

Early life

editNils Olof Thorbjörn Fälldin[3] was born on 24 April 1926[4][5] in Högsjö parish, Ångermanland. He was the son of the farmer Nils Johan Fälldin and his wife Hulda (née Olsson),[6] who were involved in agriculturally focused political and civic associations.[2] Fälldin grew up in a farming family in Ångermanland.[1][4] He completed his formal schooling at the age of 19.[5]

In 1956, he and his wife, as a newlywed young couple, took over a small farm. However, the farming authorities did not approve the purchase, as the farm was considered too small and too run down for production, and so refused to provide farm subsidies. This fight led him into the youth branch of the Swedish agrarian party Farmers' League (Bondeförbundet), which in 1958 changed its name to the Centre Party. He and his family maintained their farm throughout his political life, and when he resigned from politics in 1985, he immediately returned to it.[7]

Political career

editEarly political career

editFälldin entered the Swedish national political stage when he was elected to the Second Chamber of the Swedish Riksdag in 1958 for the agrarian-rooted Centre Party.[2][5][8] He was part of a younger generation of activists within the party that wished to expand its appeal to urban voters. He was distinguished by his skepticism of social democracy and trade unions.[2] He lost the seat by 11 votes in 1964.[5] Fälldin was then elected to the party board and met with local party organizations, which raised his profile among the Centrists. In 1966 he gained a seat in the First Chamber, where he befriended the leader of the Liberal Party. Fälldin then regained his Second Chamber seat in 1968.[9]

Competing against his rival Johannes Antonsson, he won a party election to became vice-chairman of the party in 1969.[5][10] Fälldin was able to secure the position without the support of the chairman, Gunnar Hedlund.[9] He succeeded Hedlund as party chairman in 1971.[10][11] Also in 1971 he became a member of the new unicameral Riksdag that replaced the bicameral.[citation needed] With Fälldin's ascension to the leadership, criticism of the Social Democratic Party increased.[11]

During the 1973 general election, Fälldin held a live televised debate against Social Democratic party leader and prime minister Olof Palme, which were in the process of becoming a staple of Swedish politics.[12] That year, Fälldin proposed that the party should merge with the Liberal Party, but he failed to gain the support of a majority of party members.[citation needed] The Centre Party received 25.1% of the votes that year, their highest share for a Riksdag election up to that point and since.[12][13]

Premiership

editDuring the 1976 election, Fälldin again debated Palme. Although Palme was perceived as a better debater, Fälldin was perceived as a having won more sympathy with voters, contrasting with Palme's aggressive style.[12] In particular, Fälldin emotionally criticized the government's proposed nuclear power program, which has been described as a turning point in the Centrists' favor.[5] During the campaign, his political opponents praised him for honesty and similarities to rural voters, but criticized his lack of foreign policy experience and his inability to understand English.[5] In the election the Social Democrats sensationally lost their majority for the first time in 40 years. The non-Socialist parties (the Centre Party, the Liberal Party and the Conservative Moderate Party) formed a coalition government, and, as the Centre Party was the largest of the three, Fälldin was elected prime minister by the Riksdag and confirmed by king Carl XVI Gustaf during a Council of State, being the first person appointed in this manner under the new 1974 Instrument of Government.[citation needed] This was the first time a member of the Centre Party headed a Swedish government since Axel Pehrsson-Bramstorp's brief government fourty years earlier, in 1936.[11]

Two years later, however, the coalition fell apart over the issue of Swedish dependency on nuclear power (with the Centre Party taking a strong anti-nuclear stand),[citation needed] which led to Fälldin's resignation on 18 October, 1978. Ola Ullsten formed a minority Liberal Party government.[14] That year, Fälldin also sued Aftonbladet for 1 krona after they published a satirical interview with him from a mental hospital in which they claimed he had schizophrenia. Fälldin claimed that this was illegal, but later lost the case.[15]

Following the 1979 election, Fälldin regained the post of prime minister, despite his party suffering major losses and losing its leading role in the centre-right camp, primarily due to public disenchantment with the Centre Party over its compromise on nuclear power with the nuclear-friendly Moderates, and he again formed a coalition government with the Liberals and the Moderates. This cabinet also lasted for two years, when disagreement over tax policies compelled the Moderates to leave the coalition. Fälldin continued as prime minister until the election in 1982, when the Social Democrats regained power as the Socialist bloc won a majority in the Riksdag.[citation needed] On 8 October 1982, Fälldin was succeeded by Palme.[14]

Post-premiership

editAfter a disastrous second election defeat in 1985, in which the party received 12.45% of votes,[13][16] Fälldin faced massive criticism from his party. He resigned as party leader on 5 December 1985.[16] He then retired from politics. His posts after that time included chairman of Föreningsbanken, Foreningen Norden, and Televerket.[17]

Membership

editFälldin was one of the board members of the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation in the 1970s.[18]

Personal life

editIn 1956, he married Solveig Öberg (born 1935), daughter of the farmer Albert Öberg and Sofia (née Näsman).[6] They had three children; Eva, Nicklas, and Pontus; as well as several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.[19]

He died at the age of 90, on 23 July 2016.[20][21] The funeral was held on 11 August 2016 in Härnösand Cathedral, and he was buried at Högsjö Cemetery in Högsjö, Härnösand Municipality.[22]

Legacy

editDuring his 27 years as a national politician, Fälldin was generally appreciated in most political camps for his straightforwardness, unpretentiousness, and willingness to listen to all views. His two periods as Prime Minister were far from easy; trying to get three very different parties to work together in a coalition, while Sweden underwent its worst recession since the 1930s.[citation needed]

Fälldin refused to allow security concerns to rule his life. During his years as prime minister, he lived on his own in a small rented apartment in central Stockholm, while his family ran the farm up in northern Sweden. He did his own cooking and carried out refuse in the morning to the communal dustbins in the backyard, before taking a brisk 15-minute walk to his office, shadowed at a distance by an unmarked police car which had been waiting outside the apartment block; his only concession to the security concerns.[citation needed]

While serving as prime minister during the U 137 crisis in October–November 1981, Fälldin is remembered for the simple answer "Hold the border!" (Håll gränsen!) to the request for instructions from the Supreme Commander of the Swedish Armed Forces when faced with a suspected Soviet raid to free the stranded submarine.[23] During the 2024 European Parliament election in Sweden, the Centre Party used the phrase as a slogan, representing the party's support of stopping imports of Russian fossil fuel and ending EU subsidies to fossil fuels.[24]

Awards and decorations

edit- Grand Cross of the Order of the White Rose of Finland (November 1990)[25]

- Commander with Star of the Royal Norwegian Order of Merit (1 July 1999)[26]

Cabinets

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Marklund, Kari, ed. (1992). "Fälldin, Thorbjörn". Nationalencyklopedin (in Swedish). Vol. 7. Höganäs: Bra Böcker. ISBN 91-7133-426-2.

- ^ a b c d Wilsford 1995, p. 133

- ^ "1991-1992". The International Who's Who (55th ed.). London: Europa Publications. 1991. p. 489. ISBN 0-946653-70-4.

- ^ a b Rising, Malin (24 July 2016). "Swedish ex-prime minister Thorbjorn Falldin dead at 90". Associated Press. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Weinraub, Bernard (21 September 1976). "Victor Over Swedish Socialists". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ a b Uddling, Hans; Paabo, Katrin, eds. (1992). Vem är det: svensk biografisk handbok. 1993 [Who is it: Swedish biographical handbook. 1993] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Norstedt. pp. 362–363. ISBN 91-1-914072-X.

- ^ Karmann, Jens (24 July 2016). "Thorbjörn Fälldin 1926–2016". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ Elgán & Scrobbie 2015, p. 93.

- ^ a b Wilsford 1995, p. 134

- ^ a b "1970-talet". Centerpartiet (in Swedish). Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Nilsson, Torbjorn (5 July 2010). "Partiernas historia: Centerpartiet" (in Swedish). Populär Historia. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Bohlin, Ira (20 September 2006). "Partiledardebatter blev viktiga inför valen" (in Swedish). Populär Historia. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Historisk statistik över valåren 1910–2022. Procentuell fördelning av giltiga valsedlar efter parti och typ av val". Statistics Sweden (in Swedish). Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ a b Elgán & Scrobbie 2015, p. xxix

- ^ Pär Fjällström (10 December 2017). Fälldin, Statsministern som blev bonde (Video) (in Swedish). Stockholm: SVT.

- ^ a b Wilsford 1995, p. 138

- ^ Svenning, Olle; T, Per (2014). Sveriges statsministrar under 100 år / Thorbjörn Fälldin (in Swedish). Albert Bonniers förlag. ISBN 9789100132453. SELIBR 13496022.

- ^ Lars Engwall (2021). "Governance of and by Philanthropic Foundations". European Review. 29 (5): 681–682. doi:10.1017/S1062798720001052.

- ^ Almgren, Christina (11 April 2011). "Thorbjörn firar med familjen". Örnsköldsviks Allehanda (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ Svensson, Frida (24 July 2016). "Thorbjörn Fälldin har avlidit – blev 90 år". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ "Swedish ex-prime minister Thorbjorn Fälldin dead at 90". The Local. 24 July 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ Stattin, Gunnar (29 July 2016). "Planerna för Fälldins begravning tar form flera toppnamn närvarar". Örnsköldsviks Allehanda (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ Wolodarski, Peter (30 October 2011). "När ryssen kom sade Fälldin: "Håll gränsen"". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ "C: Förbjud fossil energiproduktion till 2035". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). 2 May 2024. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ "Thorbjörn Fälldin". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). 12 November 1990. p. 10. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ "Tildelinger av ordener og medaljer" [Awards of orders and medals]. www.kongehuset.no (in Norwegian). Royal Court of Norway. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

Bibliography

edit- Elgán, Elisabeth; Scrobbie, Irene (2015). Historical Dictionary of Sweden (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-5070-3.

- Wilsford, David, ed. (1995). Political leaders of contemporary Western Europe: a biographical dictionary. Greenwood. pp. 132–39. ISBN 978-0-313-28623-0.