Dent's disease

Dent's disease (or Dent disease) is a rare X-linked recessive inherited condition that affects the proximal renal tubules[1] of the kidney. It is one cause of Fanconi syndrome, and is characterized by tubular proteinuria, excess calcium in the urine, formation of calcium kidney stones, nephrocalcinosis, and chronic kidney failure.

| Dent's disease | |

|---|---|

| |

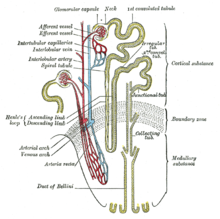

| Nephron of the kidney without juxtaglomerular apparatus | |

| Specialty | Urology |

| Named after | Charles Enrique Dent |

"Dent's disease" is often used to describe an entire group of familial disorders, including X-linked recessive nephrolithiasis with kidney failure, X-linked recessive hypophosphatemic rickets, and both Japanese and idiopathic low-molecular-weight proteinuria.[2] About 60% of patients have mutations in the CLCN5 gene (Dent 1), which encodes a kidney-specific chloride/proton antiporter, and 15% of patients have mutations in the OCRL1 gene (Dent 2).[3]

Signs and symptoms

editDent's disease often produces the following signs and symptoms:[4]

- Extreme thirst combined with dehydration, which leads to frequent urination

- Nephrolithiasis (kidney stones)

- Hypercalciuria (high urine calcium - >300 mg/d or >4 mg/kg per d with normal levels blood/serum calcium)

- Aminoaciduria (amino acids in urine)

- Phosphaturia (phosphate in urine)

- Glycosuria (glucose in urine)

- Kaliuresis (potassium in urine)

- Hyperuricosuria (excessive amounts of uric acid in the urine)

- Impaired urinary acidification

- Rickets

In a study of 25 patients with Dent's disease,[5] 9 of 15 men, and one of 10 women had end-stage kidney disease by the age of 47.[6]

Genetics

editDent disease 1

editDent's disease is a X-linked recessive disorder. The males are prone to manifesting symptoms in early adulthood with symptoms of calculi, rickets or even with kidney failure in more severe cases.[4]

In humans, gene CLCN5 is located on chromosome Xp11.22, and has a 2238-bp coding sequence that consists of 11 exons that span 25 to 30 kb of genomic DNA and encode a 746-amino-acid protein.[7] CLCN5 belongs to the family of voltage-gated chloride channel genes (CLCN1-CLCN7, CLCKa and CLCKb) that have about 12 transmembrane domains. These chloride channels have an important role in the control of membrane excitability, transepithelial transport, and possibly cell volume.[8]

The mechanisms by which CLC-5 dysfunction results in hypercalciuria and the other features of Dent's disease remain to be elucidated. The identification of additional CLCN5 mutations may help in these studies.[9]

Dent disease 2

editDent disease 2 (nephrolithiasis type 2) is associated with the OCRL gene.[10][11] Both Lowe syndrome (oculocerebrorenal syndrome) and Dent disease can be caused by truncating or missense mutations in OCRL.

Diagnosis

editDiagnosis is based on genetic study of CLCN5 gene.[citation needed]

Treatment

editAs of today, no agreed-upon treatment of Dent's disease is known and no therapy has been formally accepted. Most treatment measures are supportive in nature:

- Thiazide diuretics (i.e. hydrochlorothiazide) have been used with success in reducing the calcium output in urine, but they are also known to cause hypokalemia.

- In rats with diabetes insipidus, thiazide diuretics inhibit the NaCl cotransporter in the renal distal convoluted tubule, leading indirectly to less water and solutes being delivered to the distal tubule.[12] The impairment of Na transport in the distal convoluted tubule induces natriuresis and water loss, while increasing the reabsorption of calcium in this segment in a manner unrelated to sodium transport.

- Amiloride also increases distal tubular calcium reabsorption and has been used as a therapy for idiopathic hypercalciuria.

- A combination of 25 mg of chlorthalidone plus 5 mg of amiloride daily led to a substantial reduction in urine calcium in Dent's patients, but urine pH was "significantly higher in patients with Dent's disease than in those with idiopathic hypercalciuria (P < 0.03), and supersaturation for uric acid was consequently lower (P < 0.03)."[13]

- For patients with osteomalacia, vitamin D or derivatives have been employed, apparently with success.

- Some lab tests on mice with CLC-5-related tubular damage showed a high-citrate diet preserved kidney function and delayed progress of kidney disease.[14]

History

editDent's disease was first described by Charles Enrique Dent and M. Friedman in 1964, when they reported two unrelated British boys with rickets associated with renal tubular damage characterized by hypercalciuria, hyperphosphaturia, proteinuria, and aminoaciduria.[15] This set of symptoms was not given a name until 30 years later, when the nephrologist Oliver Wrong more fully described the disease.[5] Wrong had studied with Dent and chose to name the disease after his mentor.[16] Dent's disease is a genetic disorder caused by mutations in the gene CLCN5, which encodes a kidney-specific voltage-gated chloride channel, a 746-amino-acid protein (CLC-5) with 12 to 13 transmembrane domains. It manifests itself through low-molecular-weight proteinuria, hypercalciuria, aminoaciduria and hypophosphataemia. Because of its rather rare occurrence, Dent's disease is often diagnosed as idiopathic hypercalciuria, i.e., excess calcium in urine with undetermined causes.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ "Dent disease" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Mayo Clinic, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Mineral Metabolism and Stone Disease Archived 2007-03-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ S. Karger AG, Basel, Truncating Mutations in the Chloride/Proton ClC-5 Antiporter Gene in Seven Jewish Israeli Families with Dent’s 1 Disease

- ^ a b "Dent disease". National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ a b Wrong OM; Norden AGW; Feest TG (1994). "Dent's disease; a familial proximal renal tubular syndrome with low-molecular-weight proteinuria, hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, metabolic bone disease, progressive kidney failure and a marked male predominance". Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 87 (8): 473–493. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14.

- ^ Burgess HK, Jayawardene SA, Velasco N (July 2001). "Dent's disease: can we slow its progression?". Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 16 (7): 1512–3. doi:10.1093/ndt/16.7.1512. PMID 11427657.

- ^ Fisher SE, van Bakel I, Lloyd SE, Pearce SH, Thakker RV, Craig IW (October 1995). "Cloning and characterization of CLCN5, the human kidney chloride channel gene implicated in Dent disease (an X-linked hereditary nephrolithiasis)". Genomics. 29 (3): 598–606. doi:10.1006/geno.1995.9960. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-CC06-6. PMID 8575751.

- ^ Jentsch TJ, Friedrich T, Schriever A, Yamada H (May 1999). "The CLC chloride channel family". Pflügers Arch. 437 (6): 783–95. doi:10.1007/s004240050847. PMID 10370055. S2CID 2602342. Archived from the original on 2001-03-18. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- ^ Yamamoto K, Cox JP, Friedrich T, et al. (August 2000). "Characterization of renal chloride channel (CLCN5) mutations in Dent's disease". J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11 (8): 1460–8. doi:10.1681/ASN.V1181460. PMID 10906159.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 300555

- ^ Hoopes RR, Shrimpton AE, Knohl SJ, et al. (February 2005). "Dent Disease with mutations in OCRL1". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76 (2): 260–7. doi:10.1086/427887. PMC 1196371. PMID 15627218.

- ^ Loffing J (November 2004). "Paradoxical antidiuretic effect of thiazides in diabetes insipidus: another piece in the puzzle". J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15 (11): 2948–50. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000146568.82353.04. PMID 15504949.

- ^ Raja KA, Schurman S, D'mello RG, et al. (December 2002). "Responsiveness of hypercalciuria to thiazide in Dent's disease". J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13 (12): 2938–44. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000036869.82685.F6. PMID 12444212.

- ^ Cebotaru V, Kaul S, Devuyst O, et al. (August 2005). "High citrate diet delays progression of renal insufficiency in the ClC-5 knockout mouse model of Dent's disease". Kidney Int. 68 (2): 642–52. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00442.x. PMID 16014041.

- ^ Dent CE, Friedman M (1964). "Hypercalcuric Rickets Associated with Renal Tubular Damage". Arch Dis Child. 39 (205): 240–9. doi:10.1136/adc.39.205.240. PMC 2019188. PMID 14169453.

- ^ "Professor Oliver Wrong (1924 - 2012)".[permanent dead link]