Faraway, So Close! (German: In weiter Ferne, so nah!) is a 1993 German fantasy film directed by Wim Wenders, who co-wrote the screenplay with Richard Reitinger and Ulrich Zieger. It is a sequel to Wenders' 1987 film Wings of Desire.[n 1] Actors Otto Sander, Bruno Ganz and Peter Falk reprise their roles as angels who have become human. The film also stars Nastassja Kinski, Willem Dafoe, and Heinz Rühmann in his last film role.

| Faraway, So Close! | |

|---|---|

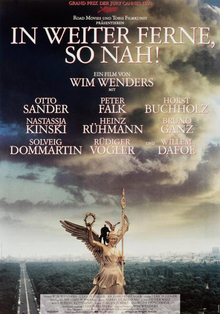

Theatrical release poster | |

| German | In weiter Ferne, so nah! |

| Directed by | Wim Wenders |

| Screenplay by | Richard Reitinger Wim Wenders Ulrich Zieger |

| Based on | Characters by Wim Wenders Peter Handke Richard Reitinger |

| Produced by | Ulrich Felsberg Michael Schwarz Wim Wenders |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jürgen Jürges |

| Edited by | Peter Przygodda |

| Music by | Laurent Petitgand Nick Cave Laurie Anderson Lou Reed |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Tobis Filmkunst |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 144 minutes (German version) |

| Country | Germany |

| Languages | German French English Italian Russian Spanish |

| Box office | $810,455[1] |

The story follows the angel Cassiel, who unlike his friend Damiel, chose not to become human despite being told of the joys of life. Cassiel only becomes human in the reunified Berlin, but quickly becomes involved in a criminal enterprise that threatens his newfound life and his friends.

Wenders opted to pursue the project, desiring to make a film set in Berlin after the fall of the Wall. Sander also wished to pursue a storyline in which his character becomes human, and contributed ideas for the plot. Faraway, So Close! won the Grand Prix du Jury at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival, but enjoyed less critical and commercial success than its predecessor.

Plot

editCassiel and Raphaella, two angels, observe the busy life of reunited Berlin. Due to their divine origin, they can hear the thoughts of the people around them, and try to console a dying man. Cassiel has been following his friend Damiel (a former angel), who senses his presence and talks about his experiences as a human. He owns a pizza parlor named Casa dell'angelo (Angel's House) and has married Marion, a trapeze artist whom he met when he was an angel. She works in a local bar in West Berlin, and the two have a young daughter, Doria.

Cassiel follows Raissa Becker, an 11-year-old girl who lives in the former East Berlin. He observes her life and notices that she and her mother Hanna Becker are being followed by Philip Winter, a detective who works for Anton Baker. Baker is an American arms dealer and pornographer who owns a transport company.

Cassiel follows Becker and Winter to an abandoned building in. As Raphaella and Cassiel sit on top of the Brandenburg Gate, he expresses a desire to experience human life. Visiting Raissa, he finds her alone at her flat and leaning over the balcony railing. As she falls, Cassiel tries to save her and suddenly becomes human, catching the child. He has to adjust to the transformation, learning to modulate the volume of his voice and to negotiate streets and avoid being hit by cars. His only possession is an angel's armor, which became tangible when he leaped into humanity. In the subway, Cassiel is tricked into gambling by Emit Flesti, losing his armor and money won during the game. Raphaella begs Flesti to give Cassiel time to understand what it is to be a human; he agrees but does not promise to stop hunting him.

Arrested and detained, Cassiel struggles to satisfy police demands for identification. He cannot give (or comprehend) his name or address, but refers the police to his friend's pizza shop. Damiel arrives at the station and takes his now human friend home. Tricked by Flesti into drinking alcohol, he becomes addicted and robs a shop with a gun taken from a teenager, who had been planning to kill his abusive stepfather. Cassiel begins begging to make his way and feigns a car accident with Baker to compel him to pay for the forging of a passport and birth certificate he has ordered under the name Karl Engel (Charles Angel). Baker hires Cassiel as his valet, to pass him cards for cheating his fellow gangsters at poker. Stopping by Casa dell'Angelo to return items borrowed from Damiel, Cassiel encounters Flesti again. He is collecting money from Damiel, after having loaned him money to set up the business. After Cassiel saves Baker's life, Baker makes Cassiel his partner. But after learning the true nature of his business, Cassiel decides to leave Baker's service and stop him. Winter is killed by Flesti.

With the help of Damiel and former angel Peter Falk, Cassiel gets into Baker's airport storage area. His team takes all the weapons and destroy the pornography copying machines. They send the weapons to a barge owned by other friends. Once having completed the plan, Cassiel feels ready to live as a human, but Flesti reports that Baker's rival, Patzke, has hijacked the barge with Baker's and Cassiel's friends inside. Becker is also captured and reunites with his sister, Hannah, on board.

Flesti reveals himself as Time and says that he has to make Cassiel understand he does not belong in the human world; he has a word written on his forehead. At a boat lift, Cassiel gets on the barge and frees Raissa, moments before being killed. Flesti slows time so the rest can take over the barge and save the entire party. Cassiel's friends are saddened by his death, but when Damiel hears a ring in his ear, he understands that Cassiel has been reinstated as an angel and is near, and Damiel laughs in joy.

Cast

edit- Otto Sander as Cassiel[n 2]

- Bruno Ganz as Damiel[n 2]

- Nastassja Kinski as Raphaella

- Solveig Dommartin as Marion

- Horst Buchholz as Tony Baker

- Rüdiger Vogler as Philip Winter[n 3]

- Heinz Rühmann as Chauffeur Konrad

- Martin Olbertz as the dying man

- Aline Krajewski as Raissa

- Monika Hansen as Hanna / Gertrud Becker

- Peter Falk as Himself[n 4]

- Lou Reed as Himself[11]

- Mikhail Gorbachev as Himself[12]

- Willem Dafoe as Emit Flesti / Time Itself[n 5]

- Tilmann Vierzig as Young Konrad

- Antonia Westphal as Young Hanna

- Hanns Zischler as Dr. Becker

- Ingo Schmitz as Anton Becker

- Günter Meisner as Forger

- Ronald Nitschke as Patzke

Themes

editWriters later assessed the film as having more religious themes than the original. Peter Hasenberg wrote it contains the two films' first reference to God, when the angels state a purpose to connect humans with "Him".[14] Andrew Tate noted a quote from Matthew 6:22 and Matthew 6:23 in the film, attributing this to Wenders personally converting back to Christianity in the time between the original and sequel.[7] Tate also noted Faraway, So Close! is followed by the 1998 U.S. remake City of Angels, which he said references "mythic phenomena".[7]

Professor Martin Jesinghausen judged the sequel to differ from the original's presumption that the Berlin Wall would never fall, and concluded the lack of divides made the sequel "less powerful".[5] Professor Roger Bromley defended Faraway, So Close! as more than a mere sequel, saying it is "fairly formless" but this is fitting for the "incomplete modernity" in film and life following the Revolutions of 1989.[15] Academic Roger Cook argued that, as with the original and Wenders' 1984 road movie Paris, Texas, Faraway, So Close! advocates for "narrative's potential to sustain both individual and cultural identity".[16]

Production

editDirector Wim Wenders' film Wings of Desire is set in Berlin at the time of the Wall. He opted to make a sequel, desiring to explore Berlin post-reunification, more so than for the sake of having a sequel,[17] though the original ends with "To be continued".[n 6] Wenders had earlier planned to make a film about the evolved Berlin in 1991, but not with Wings of Desire characters, only doing so upon considering that only his angels could observe the moral changes he found problematic.[2]

Otto Sander, who reprises his role as the angel Cassiel, wished to see him become human, an idea unresolved in the first film.[19][n 7] Wenders credited Sander with the idea of Cassiel descending into crime.[21] Richard Reitinger and Ulrich Ziegler wrote the bulk of the screenplay, with Wenders also credited.[22] Due to the larger budget than the original, Road Movies Filmproduktion made the film without original producer Anatole Dauman and Argos.[23]

The film features cameo appearances by the singer Lou Reed, the American actor Peter Falk, reprising his role from the first film,[11] and former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, all of whom play themselves. Gorbachev had never acted in a film before.[13] His appearance was rare, but not entirely unprecedented for a politician, as Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam and New York Mayor John Lindsay had appeared in films.[11] Heinz Rühmann was also cast, and his death in October 1994 made this his last role.[24] Much of the first three weeks of photography went unused in the final edit, due to its influence from Wings of Desire and Wenders' aversion to sequels.[2]

Music

editThe Faraway, So Close!: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack was released on September 6, 1993, in Europe and Canada, and January 25, 1994, in the United States by EMI Electrola.[25][26] The twenty-track album has a run time of 76:33.

The soundtrack mix of the U2 songs "Stay (Faraway, So Close!)" and "The Wanderer" are augmentations of the original versions included on the July 1993 release of Zooropa.[27]

- "Faraway So Close" ~ 3:56 ~ Nick Cave

- "Stay (Faraway, So Close!)" (soundtrack mix) ~ 6:06 ~ U2

- "Why Can't I Be Good" ~ 4:22 ~ Lou Reed[26]

- "Chaos" ~ 4:51 ~ Herbert Grönemeyer

- "Travelin On" ~ 3:49 ~ Simon Bonney

- "The Wanderer" (soundtrack mix) ~ 5:16 ~ U2 (featuring Johnny Cash)

- "Cassiel's Song" ~ 3:36 ~ Nick Cave

- "Slow Tango" ~ 3:29 ~ Jane Siberry

- "Call Me" ~ 4:08 ~ The House of Love

- "All God's Children" ~ 4:42 ~ Simon Bonney

- "Tightrope" ~ 3:18 ~ Laurie Anderson

- "Speak My Language" ~ 3:36 ~ Laurie Anderson

- "Victory" ~ 4:06 ~ Laurent Petitgand

- "Gorbi" ~ 2:51 ~ Laurent Petitgand

- "Konrad (1st part)" ~ 1:56 ~ Laurent Petitgand

- "Konrad (2nd part)" ~ 3:41 ~ Laurent Petitgand

- "Firedream" ~ 3:01~ Laurent Petitgand

- "Allegro" ~ 3:27 ~ Laurent Petitgand

- "Engel" ~ 4:44 ~ Laurent Petitgand

- "Mensch" ~ 1:38 ~ Laurent Petitgand

Release

editFaraway, So Close! competed at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1993.[28] In late 1993, it made its U.S. debut at the Telluride Film Festival, where Wim Wenders introduced it personally.[2] It also reached theatres in Germany.[29]

A limited release in the U.S. followed in December.[2] In the film's international release, press releases straightforwardly noted "Faraway, So Close marks Mikhail Gorbachev's feature film debut".[13] On its first weekend, it made $55,019 and finished its run grossing $810,455 in North America.[1]

Reception

editOn review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Faraway, So Close! holds a 54% approval rating based on 13 reviews, with an average rating of 5.80/10.[30]

The New York Times critic Caryn James described the film as "lyrical and profoundly goofy" and "one of the more intriguing messes on screen".[13] Desson Howe wrote in The Washington Post that while the sequel was not totally unsuccessful, "the narrative journey up to this point has been so frustrating and inconsistent, the conclusion feels like an afterthought".[3] Time's Richard Corliss summarized it as "a wondrous mess".[4] The Los Angeles Times critic Kevin Thomas was more positive, assessing it as "just as luminous as" and "a considerably more complex film than Wings of Desire."[31] Roger Ebert contemplated the casting of Nastassja Kinski as a new angel character, writing, "A few years ago Kinski would have been cast as one of the humans. Now her face can reflect the sadness, the experience, the wisdom that allows her to be an angel", explaining his argument by saying that at age 30, Kinski resembled her now-dead father Klaus in "The deep-set eyes. The hurt in the lips."[32] New York responded to the casting of Gorbachev with a simple "Go figure".[12]

In his 2007 Movie Guide, Leonard Maltin gave it two and a half stars, and approved of the casting.[33] Time Out dismissed it as "a considerable disappointment".[34]

The film won the Grand Prix du Jury at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival,[28] and Best Cinematography for Jürgen Jürges at the German Film Awards.[35] Its song "Stay" was also nominated for the Golden Globe for Best Song.[36]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Although Wenders rejected the notion of the sequel,[2] critics[3][4] and scholars[5][6] recognized it as such nevertheless. Writer Andrew Tate described it as a "semisequel" instead.[7]

- ^ a b While working on the original, Wenders found the names Cassiel and Damiel in an encyclopedia about angels.[8]

- ^ In Wenders' filmography, beginning with Alice in the Cities, Vogler played a character named Phillip Winter numerous times, though the various Winters may not be the same character.[9]

- ^ Falk joined the cast of the original as himself, with Wenders planning the role of a former angel when assistant Claire Denis suggested the Columbo star would be familiar to everyone.[10]

- ^ Dafoe's character names are a simplistic anagram.[13]

- ^ Professor Detweiler connected the "To be continued" title with Faraway, So Close!.[6] Academic Helen Stoddart noted the title is accompanied by the final French dialogue "We have embarked", arguing this suggests "final movement to a new beginning".[18]

- ^ This excludes a deleted scene in Wings of Desire, in which Cassiel becomes human and engages in a pie fight with the other characters.[20]

References

edit- ^ a b "Faraway, So Close! (1993)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Willman, Chris (31 December 1993). "Fighting the Ghost of 'Wings of Desire' : Movies: Wim Wenders swears 'Faraway, So Close'--a film with much the same cast, characters, setting, design and thematic concerns as his beloved 1986 tone poem--is not a real sequel. Just ask him". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ a b Howe, Desson (11 February 1994). "Faraway, So Close". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ a b Corliss, Richard (10 January 1994). "Date with an angel, take two". Time. Vol. 143, no. 2. p. 56.

- ^ a b Jesinghausen 2000, p. 80.

- ^ a b Detweiler 2017.

- ^ a b c Tate 2011, p. 23.

- ^ Wenders, Wim (9 November 2009). "On Wings of Desire". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ D'Angelo, Mike (28 May 2016). "Criterion offers a loose trilogy from Wim Wenders, king of the road movie". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Feaster, Felicia. "Wings of Desire". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ a b c Jackson, Kevin (1 July 1994). "FILM / Didn't you used to be . . ?: Faraway, So Close: a new film by Wim Wenders starring Nastassja Kinski and the former president of the USSR. Kevin Jackson on the cameo". The Independent. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ a b Morgan, Melissa (13 September 1993). "Movies". New York. p. 43.

- ^ a b c d James, Caryn (22 December 1993). "Review/Film: Faraway, So Close; Wim Wenders's Angels Drop In for Another Visit". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Hasenberg 1997, p. 54.

- ^ Bromley 2001, p. x.

- ^ Cook 1997, p. 128.

- ^ Bromley 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Stoddart 2000, p. 179.

- ^ Kenny, J.M.; Sander, Otto (2009). "The Angels Among Us". Wings of Desire (Blu-ray). The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Erickson 2004, p. 336.

- ^ Kenny, J.M.; Wenders, Wim (2009). "The Angels Among Us". Wings of Desire (Blu-ray). The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Fry 2008, p. 88.

- ^ Lerner, Dietlind (30 January 1994). "Wenders takes wing". Variety. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ "Kurzbiografie: Heinz Rühmann (1902-1994)". Spiegel Online (in German). 27 February 2002. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ McGee 2011.

- ^ a b Reed 2008, p. 575.

- ^ Calhoun 2012, p. 149.

- ^ a b "Awards 1993 : Competition". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "On a wim". Billboard. Vol. 105, no. 27. 3 July 1993. p. 40.

- ^ "Faraway, So Close!". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (21 December 1993). "Movie Review: 'Faraway, So Close': Wim Wenders' Spiritual Odyssey". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (20 May 1993). "A Meditation On 2 Faces Of Film". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ Maltin 2006, p. 421.

- ^ TCH (10 September 2012). "Faraway, So Close". Time Out. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "Deutscher Filmpreis, 1994" (in German). Deutscher Filmpreis. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ "Faraway, So Close". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

Bibliography

edit- Bromley, Roger (2001). From Alice to Buena Vista: The Films of Wim Wenders. Westport, Connecticut and London: Praeger. ISBN 0275966488.

- Calhoun, Scott (2012). Exploring U2: Is This Rock 'n' Roll?. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810881570.

- Cook, Roger F. (1997). The Cinema of Wim Wenders: Image, Narrative, and the Postmodern Condition. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0814325785.

- Detweiler, Craig (2017). "10. Wings of Desire". God in the Movies: A Guide for Exploring Four Decades of Film. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1493410590.

- Erickson, Glenn (2004). "Wings of Desire". DVD Savant. Wildside Press. ISBN 0809510987.

- Fry, Carrol Lee (2008). Cinema of the Occult: New Age, Satanism, Wicca, and Spiritualism in Film. Associated University Presses. ISBN 978-0934223959.

- Hasenberg, Peter (1997). "The 'Religious' in Film: From King of Kings to The Fisher King". New Image of Religious Film. Franklin, Wisconsin: Sheed & Ward. ISBN 1556127618.

- Jesinghausen, Martin (2000). "The Sky over Berlin as Transcendental Space: Wenders, Doblin and the 'Angel of History'". Spaces in European Cinema. Intellect Books. ISBN 1841500046.

- Maltin, Leonard (2006). Leonard Maltin's 2007 Movie Guide. Penguin Group (USA) Incorporated. ISBN 0452287561.

- McGee, Matt (2011). "1994". U2: A Diary. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0857127433.

- Reed, Lou (2008). Pass Thru Fire: The Collected Lyrics. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0786726028.

- Stoddart, Helen (2000). "Flights of Fantasy: Representing the Female Aerialist". Rings of Desire: Circus History and Representation. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719052343.

- Tate, Andrew (2011). "Angels". Encyclopedia of Religion and Film. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313330728.