Fayetteville (/ˈfeɪətvɪl, ˈfɛdvɪl/ FAY-ət-vil, FED-vil)[8] is a city in and the county seat of Cumberland County, North Carolina, United States.[9] It is best known as the home of Fort Liberty, a major U.S. Army installation northwest of the city.

Fayetteville | |

|---|---|

Downtown Fayetteville | |

| Nicknames: America's Can Do City, All-American City, City of Dogwoods, Fayettenam, The Ville, 2-6, The Soldier City | |

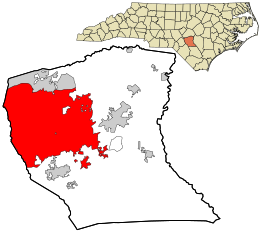

Location in Cumberland County and North Carolina | |

| Coordinates: 35°05′06″N 78°58′38″W / 35.08500°N 78.97722°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | North Carolina |

| County | Cumberland |

| Settled | 1783 |

| Named for | Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Mitch Colvin (D)[1] |

| • City Manager | Douglas J. Hewett |

| Area | |

• Total | 150.08 sq mi (388.71 km2) |

| • Land | 148.26 sq mi (383.99 km2) |

| • Water | 1.82 sq mi (4.73 km2) 1.21% |

| Elevation | 223 ft (68 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 208,501 |

• Estimate (2023)[5] | 209,749 |

| • Rank | 110th In the United States 6th in North Carolina |

| • Density | 1,406.34/sq mi (542.99/km2) |

| • Urban | 325,008 (US: 125th)[4] |

| • Urban density | 1,658.8/sq mi (640.5/km2) |

| • Metro | 392,336 (US: 142nd) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 28301, 28302, 28303, 28304, 28305, 28306, 28307 (Fort Liberty), 28308 (Pope AAF), 28309, 28310 (Fort Liberty), 28311, 28312, 28314 |

| Area codes | 910, 472 |

| FIPS code | 37-22920[7] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2403604[3] |

| Primary Airport | Fayetteville Regional Airport |

| Public transportation | Fayetteville Area System of Transit |

| Website | www |

Fayetteville has received the All-America City Award from the National Civic League three times. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 208,501,[5] It is the 6th-most populous city in North Carolina. Fayetteville is in the Sandhills in the western part of the Coastal Plain region, on the Cape Fear River.

With an estimated population of 392,336 in 2023, the Fayetteville metropolitan area is the second-most populous in southeastern North Carolina and 142th-most populous in the United States.[6] Suburban areas of metro Fayetteville include Fort Liberty, Hope Mills, Spring Lake, Raeford, Pope Field, Rockfish, Stedman, and Eastover.

History

editEarly settlement

editThe area of present-day Fayetteville was historically inhabited by various Siouan Native American peoples, such as the Eno, Shakori, Waccamaw, Keyauwee, and Cape Fear people. They followed successive cultures of other indigenous peoples in the area for more than 12,000 years.

After the violent upheavals of the Yamasee War and Tuscarora Wars during the second decade of the 18th century, the colonial government of North Carolina encouraged colonial settlement along the upper Cape Fear River, the only navigable waterway entirely within the colony. Two inland settlements, Cross Creek and Campbellton, were established by Scots from Campbeltown, Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

Merchants in Wilmington wanted a town on the Cape Fear River to secure trade with the frontier country. They were afraid people would use the Pee Dee River and transport their goods to Charleston, South Carolina. The merchants bought land from Newberry in Cross Creek. Campbellton became a place where poor whites and free blacks lived and gained a reputation for lawlessness.[10][11]

In 1783, Cross Creek and Campbellton united, and the new town was incorporated as Fayetteville in honor of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, a French military hero who significantly aided the American forces during the war.[12] Fayetteville was the first city to be named in his honor in the United States.[12] Lafayette visited the city on March 4 and 5, 1825, during his grand tour of the United States.[12]

American Revolution

editThe local region was heavily settled by Scots in the mid/late 1700s, and most of these were Gaelic-speaking Highlanders. The vast majority of Highland Scots, recent immigrants, remained loyal to the British government and rallied to the call to arms from the Royal Governor. Despite this, they were eventually defeated by a larger Revolutionary force at the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge. The area also included several active Revolutionaries.

In late June 1775, residents drew up the "Liberty Point Resolves," which preceded the Declaration of Independence by a little more than a year. It said,

"This obligation to continue in full force until a reconciliation shall take place between Great Britain and America, upon constitutional principles, an event we most ardently desire; and we will hold all those persons inimical to the liberty of the colonies, who shall refuse to subscribe to this Association; and we will in all things follow the advice of our General Committee respecting the purposes aforesaid, the preservation of peace and good order, and the safety of individual and private property."

Robert Rowan, who apparently organized the group, signed first.

Robert Rowan (circa 1738–1798) was one of the area's leading public figures of the 18th century. A merchant and entrepreneur, he settled in Cross Creek in the 1760s. He served as an officer in the French and Indian War, as sheriff, justice and legislator, and as a leader of the Patriot cause in the Revolutionary War. Rowan Street and Rowan Park in Fayetteville and a local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution are named for him, though Rowan County (founded in 1753) was named for his uncle, Matthew Rowan.

Flora MacDonald (1722–1790), a Scots Highland woman known for aiding Bonnie Prince Charlie after his Highlander army's defeat at Culloden in 1746, lived in North Carolina for about five years. She was a staunch Loyalist and aided her husband in raising the local Scots to fight for the King against the Revolution.

Seventy-First Township in western Cumberland County (now a part of Fayetteville) is named for a British regiment during the American Revolution – the 71st Regiment of Foot or "Fraser's Highlanders", as they were first called.

Post-revolution

editFayetteville had what is sometimes called its "golden decade" during the 1780s. It was the site in 1789 for the state convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution, and for the General Assembly session that chartered the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Fayetteville lost out to the future city of Raleigh in the bid to become the permanent state capital.

In 1793, the Fayetteville Independent Light Infantry formed and is still active as a ceremonial unit. It is the second-oldest militia unit in the country.

Henry Evans (circa 1760–1810), a free black preacher, is locally known as the "Father of Methodism" in the area. Evans was a shoemaker by trade and a licensed Methodist preacher. He met opposition from whites when he began preaching to enslaved people in Fayetteville, but he later attracted whites to his services. He is credited with building the first church in town, the African Meeting House, in 1796. Evans Metropolitan AME Zion Church is named in his honor.

On March 4–5, 1825, General Lafayette visited his namesake town - the first one named for him and the only one he personally visited[13] as part of his 1824-1825 tour of all the states as "The Nation's Guest." Admirers stood in mud and pouring rain to welcome him. He was feted with a formal dinner, a ball, and multiple military displays.[14]

Antebellum

editFayetteville had 3,500 residents in 1820, but Cumberland County's population still ranked as the second most urban in the state, behind New Hanover County (Wilmington). Its "Great Fire" of 1831 was believed to be one of the worst in the nation's history, despite no deaths associated with the incident. Hundreds of homes, businesses, and most of the best-known public buildings were lost, including the old "State House". Fayetteville leaders moved quickly to help the victims and rebuild the town.[15]

There was no point in rebuilding the State House since the state government was firmly installed in Raleigh. On its site, the city built a Market House, recreating the city around it just as it had previously surrounded the State House. The new building had a covered area under which business could be conducted since every store in Fayetteville had been destroyed in the fire. Completed in 1832, it became the town's and county's administrative building. It was a town market until 1906 and served as Fayetteville Town Hall until 1907. Currently (2020), it is a local history museum.

The Civil War era through late 19th century

editIn March 1865, Gen. William T. Sherman and his 60,000-man army attacked Fayetteville and destroyed the Confederate arsenal (designed by the Scottish architect William Bell).[16] Sherman's troops also destroyed foundries and cotton factories, and the offices of The Fayetteville Observer. Not far from Fayetteville, Confederate and Union troops engaged in the last cavalry battle of the Civil War, the Battle of Monroe's Crossroads.

Downtown Fayetteville was the site of a skirmish, as Confederate Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton and his men surprised a cavalry patrol, killing 11 Union soldiers and capturing a dozen on March 11, 1865.

During the late nineteenth century, North Carolina adopted Jim Crow laws that imposed racial segregation.

20th century to present

editCumberland County's population increased in the post-World War II years, with its 43% increase in the 1960s the largest in any of North Carolina's 100 counties. Construction was fast-paced as shopping developments, and suburban subdivisions began to spread outside the Fayetteville city limits toward Fort Liberty and Pope Air Force Base. The Fayetteville and Cumberland County school systems moved toward integration gradually, beginning in the early 1960s; busing brought about wider-scale student integration in the 1970s.

Segregation of public facilities continued. Marches and sit-ins during the Civil Rights Movement, with students from Fayetteville State Teachers College (Fayetteville State University) at the forefront, led to the end of whites-only service at restaurants and segregated seating in theaters. Blacks and women gained office in significant numbers from the late 1960s to the early 1980s.

The Vietnam Era was a time of change in the Fayetteville area. From 1966 to 1970, more than 200,000 soldiers trained at Fort Bragg (now Fort Liberty) before leaving for Vietnam. This buildup stimulated area businesses. Anti-war protests in Fayetteville drew national attention because of Fort Bragg, a city that generally supported the war. Anti-war groups invited the actress and activist Jane Fonda to Fayetteville to participate in three anti-war events. The era also saw an increase in crime and drug addiction, especially along Hay Street, with media giving the city the nickname "Fayettenam".[17] At this time, Fayetteville also made headlines after Army doctor Jeffrey R. MacDonald murdered his pregnant wife and two daughters in their Ft. Bragg home in 1970; the book and movie Fatal Vision were based on these events.

To combat the dispersal of suburbanization, Fayetteville has worked to redevelop its downtown through various revitalization projects; it has attracted large commercial and defense companies such as Purolator, General Dynamics and Wal-Mart Stores and Distribution Center. Development of the Airborne & Special Operations Museum, Fayetteville Area Transportation Museum, Fayetteville Linear Park, and Fayetteville Festival Park, which opened in late 2006, have added regional attractions to the center.

In the first decade of the 21st century, the towns and rural areas surrounding Fayetteville had rapid growth. Suburbs such as Hope Mills, Raeford, and Spring Lake had population increases.

In 2005, Congress passed the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Act, resulting in several new commands relocating to Fort Bragg. These include the U.S. Army Forces Command (FORSCOM) and U.S. Army Reserve Command, both of which relocated from Fort McPherson in Atlanta. More than 30,000 people were expected to relocate to the area with associated businesses and families. FORSCOM awards over $300 billion in contracts annually.[18]

In the November/December 2009 issue of Where to Retire, the magazine named Fayetteville as one of the best places to retire in the United States for military retirements.[19]

In April 2019, a report by GoBankingRates (which analyzed data from 175 American cities) listed Fayetteville as one of the top ten American cities at risk of a severe housing crash. 26.8% of home mortgages in Fayetteville were listed as being "under water", while the median home value was listed as $108,000.[20]

In December 2015, Fayetteville unveiled the Guinness World Record for the biggest Christmas stocking, weighing approximately 1,600 pounds (730 kg), and measuring 74.5 x 139 feet.[21]

Fort Liberty and Pope Army Airfield

editFort Liberty and Pope Army Airfield Field are in the northern part of the city of Fayetteville.[22][23]

Several U.S. Army airborne units are stationed at Fort Liberty, most prominently the XVIII Airborne Corps HQ, the 82nd Airborne Division, the United States Army Special Operations Command, the 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne), and the United States Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School.

Fort Bragg (now Fort Liberty) was the home of the Field Artillery at the onset of World War II. All the Army's artillery units east of the Mississippi River were based at the post, about 5,000 troops. Soldiers tested the Army's new bantam car, soon known as the Jeep, although most of the power to move artillery still came from horses and burros. On September 12, 1940, the Army contracted to expand the post, bringing the 9th Infantry Division to Fort Bragg.

The mission of Pope Field is to provide airlift to American armed forces and humanitarian missions flown worldwide. Pope Field mainly includes air transportation for the 82nd Airborne, among other airborne units on Fort Liberty.

All of Pope's fighter jet squadrons have been relocated to Moody AFB, Georgia. The central entity at Pope is now the Air Force Reserve, although they still have a small number of active personnel.

In September 2008, Fayetteville annexed 85% of Fort Bragg (now Fort Liberty), bringing the city's population to 206,000. Fort Liberty retains its police, fire, and EMS services. Fayetteville hopes to attract large retail businesses to the area using the new population figures.[24]

Sanctuary community for military families

editOn September 5, 2008, Cumberland County announced it was the "World's First Sanctuary for Soldiers and Their Families"; it marked major roads with blue and white "Sanctuary" signage. Within the county, soldiers were to be provided with local services, ranging from free childcare to job placement for soldiers' spouses.[25]

Five hundred volunteers have signed up to watch over military families. They were recruited to offer one-to-one services; member businesses will also offer discounts and preferential treatment. Time magazine recognized Fayetteville for its support of military families and identified it as "America's Most Pro-Military Town".[26]

National Register of Historic Places

editGeography

editThe city limits extend west to the Hoke boundary. It is bordered on the north by the town of Spring Lake.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Fayetteville has a total area of 150.08 square miles (388.7 km2), of which 148.26 square miles (384.0 km2) is land and 1.82 square miles (4.7 km2) (1.21%) is water.[2]

Topography

editFayetteville is in the Sandhills of North Carolina, which are between the coastal plain to the southeast and the Piedmont to the northwest. The city is built on the Cape Fear River, a 202-mile-long (325 km) river that originates in Haywood and empties into the Atlantic Ocean. Carver's Falls, measuring 150 feet (46 m) wide and two stories tall is on Carver Creek, a tributary of the Cape Fear, just northeast of the city limits. Cross Creek rises on the west side of Fayetteville and flows through to the east side of Fayetteville into the Cape Fear River.

Climate

editFayetteville is located in the humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) zone, with mostly moderate temperatures year round. Winters are mild but can get cool, with snow occurring a few days per year. Summers are hot, with levels of humidity that can cause spontaneous thunderstorms and rain showers. Temperature records range from −5 °F (−21 °C) on February 13, 1899, to 110 °F (43 °C) on August 21, 1983, which was the highest temperature ever recorded in the State of North Carolina. On April 16, 2011, Fayetteville was struck by an EF3 tornado during North Carolina's largest tornado outbreak. Surrounding areas such as Sanford, Dunn, and Raleigh were also affected.[27]

| Climate data for Fayetteville, North Carolina (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1910–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) |

85 (29) |

91 (33) |

96 (36) |

102 (39) |

106 (41) |

107 (42) |

110 (43) |

106 (41) |

101 (38) |

89 (32) |

86 (30) |

110 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 74.0 (23.3) |

77.3 (25.2) |

83.1 (28.4) |

88.0 (31.1) |

93.5 (34.2) |

97.8 (36.6) |

99.1 (37.3) |

97.9 (36.6) |

93.2 (34.0) |

87.7 (30.9) |

80.5 (26.9) |

74.7 (23.7) |

100.5 (38.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 54.0 (12.2) |

57.8 (14.3) |

65.3 (18.5) |

74.8 (23.8) |

82.1 (27.8) |

88.5 (31.4) |

91.4 (33.0) |

89.3 (31.8) |

83.9 (28.8) |

74.8 (23.8) |

64.9 (18.3) |

56.8 (13.8) |

73.6 (23.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.0 (6.7) |

47.0 (8.3) |

53.8 (12.1) |

62.8 (17.1) |

70.9 (21.6) |

78.3 (25.7) |

81.7 (27.6) |

79.8 (26.6) |

74.2 (23.4) |

63.8 (17.7) |

53.6 (12.0) |

46.5 (8.1) |

63.0 (17.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 34.0 (1.1) |

36.2 (2.3) |

42.3 (5.7) |

50.8 (10.4) |

59.7 (15.4) |

68.2 (20.1) |

71.9 (22.2) |

70.2 (21.2) |

64.6 (18.1) |

52.9 (11.6) |

42.3 (5.7) |

36.3 (2.4) |

52.4 (11.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 17.0 (−8.3) |

21.1 (−6.1) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

34.0 (1.1) |

45.5 (7.5) |

56.5 (13.6) |

64.1 (17.8) |

61.7 (16.5) |

52.3 (11.3) |

36.8 (2.7) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

15.3 (−9.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −1 (−18) |

1 (−17) |

14 (−10) |

22 (−6) |

34 (1) |

44 (7) |

51 (11) |

46 (8) |

40 (4) |

21 (−6) |

15 (−9) |

2 (−17) |

−1 (−18) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.15 (80) |

2.78 (71) |

3.08 (78) |

3.15 (80) |

3.11 (79) |

4.89 (124) |

4.95 (126) |

5.36 (136) |

4.87 (124) |

3.23 (82) |

3.04 (77) |

2.97 (75) |

44.58 (1,132) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.4 | 8.9 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 10.6 | 11.1 | 11.6 | 12.0 | 9.6 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 9.4 | 117.7 |

| Source: NOAA[28][29] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 1,536 | — | |

| 1820 | 3,532 | — | |

| 1830 | 2,868 | −18.8% | |

| 1840 | 4,285 | 49.4% | |

| 1850 | 4,646 | 8.4% | |

| 1860 | 4,790 | 3.1% | |

| 1870 | 4,660 | −2.7% | |

| 1880 | 3,485 | −25.2% | |

| 1890 | 4,222 | 21.1% | |

| 1900 | 4,670 | 10.6% | |

| 1910 | 7,045 | 50.9% | |

| 1920 | 8,877 | 26.0% | |

| 1930 | 13,049 | 47.0% | |

| 1940 | 17,428 | 33.6% | |

| 1950 | 34,715 | 99.2% | |

| 1960 | 47,106 | 35.7% | |

| 1970 | 53,510 | 13.6% | |

| 1980 | 59,507 | 11.2% | |

| 1990 | 112,948 | 89.8% | |

| 2000 | 121,015 | 7.1% | |

| 2010 | 200,782 | 65.9% | |

| 2020 | 208,501 | 3.8% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 209,749 | [5] | 0.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[30] 2010[31] 2020[5] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[32] | Pop 2010[33] | Pop 2020[34] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 56,419 | 82,797 | 71,917 | 46.62% | 41.28% | 34.49% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 50,656 | 81,768 | 87,913 | 41.86% | 40.77% | 41.82% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 1,234 | 1,907 | 1,993 | 1.02% | 0.95% | 0.96% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 2,606 | 5,147 | 6,487 | 2.15% | 2.57% | 3.11% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 234 | 823 | 980 | 0.19% | 0.41% | 0.47% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 334 | 466 | 1,382 | 0.28% | 0.23% | 0.66% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 2,670 | 7,400 | 12,280 | 2.21% | 3.69% | 5.89% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 6,862 | 20,256 | 26,269 | 5.67% | 10.10% | 12.60% |

| Total | 121,015 | 200,564 | 208,501 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 208,501 people, 82,087 households, and 46,624 families residing in the city.[35]

2010 census

editAt the 2010 census, there were 200,564 people, 78,274 households, and 51,163 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,401 inhabitants per square mile (541/km2). There were 87,005 housing units at an average density of 230.3 units/km2 (596.3 persons/sq mi). The racial composition of the city was 45.7% White, 41.9% Black or African American, 2.6% Asian American, 1.1% Native American, 0.4% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 3.3% some other race, and 4.9% two or more races. 10.1% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[36]

There were 78,274 households, out of which 36.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.3% were headed by married couples living together, 19.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.6% were non-families. 28.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.3% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45, and the average family size was 3.02.[36]

In the city the population was spread out, with 25.8% under the age of 18, 14.4% from 18 to 24, 28.5% from 25 to 44, 21.5% from 45 to 64, and 9.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29.9 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.5 males.[36]

In 2013, the estimated median annual income for a household in the city was $44,924, and the median income for a family was $49,608. Male full-time workers had a median income of $37,371 versus $32,208 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,362. 18.4% of the population and 16.2% of families were below the poverty line. 27.1% of those under the age of 18 and 9.8% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[37]

On September 30, 2005, Fayetteville annexed 27 square miles (70 km2) and 46,000 residents. Some affected residents and developers challenged the annexation in the courts, but were ultimately unsuccessful. The exception was the Gates Four neighborhood which won its case against annexation despite the annexation of all surrounding neighborhoods.[38][39][40]

Religion

editFounded in Wade in 1758, Old Bluff Presbyterian Church is one of the oldest churches in the Upper Cape Fear Valley. The fourth Sunday of September each year is the annual Old Bluff Reunion; it is open to the public.[41] Bluff Presbyterian Church maintains a detailed history at its website.[42]

Hundreds of houses of worship have been established in and around Cumberland County, including Catholic, Baptist, Pentecostal, Methodist and Presbyterian churches, which have the largest congregations.[43] Fayetteville is also home to Congregation Beth Israel, formed in 1910 by the Jewish families of Fayetteville.

Fayetteville is home to St. Patrick Church, the oldest Catholic parish in the state, dating back to the 18th century.[44][third-party source needed]

The Masjid Omar ibn Sayyid mosque was named after Omar ibn Said, an African Muslim who was jailed as a fugitive slave and sold in Fayetteville in the 19th century. Visitors to the mosque can find historical information about him and the Muslim community.[45] Additionally, a historical marker to ibn Said was cast along Murchison Road in 2010,[46] the first roadside in North Carolina to recognize a Muslim.[47]

Economy

editFort Liberty is the backbone of the county's economy. Fort Liberty and Pope Field pump about $4.5 billion a year into the region's economy,[48] making Fayetteville one of the best retail markets in the country. Fayetteville serves as the region's hub for shops, restaurants, services, lodging, health care, and entertainment.

As of March 2019, Fayetteville reflected an unemployment rate of 5.2%, which is higher than the national average of 3.8% and the North Carolina average of 4%.[49]

Top employers

editAccording to the Fayetteville 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[50] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Department of Defense (Civilian) (Fort Liberty) | 14,036 |

| 2 | Cape Fear Valley Health System | 7,000 |

| 3 | Cumberland County Public School System | 6,042 |

| 4 | Wal-Mart | 3,956 |

| 5 | Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company | 2,500 |

| 6 | Cumberland County Government | 2,095 |

| 7 | Veterans Administration | 2,000 |

| 8 | City of Fayetteville | 1,776 |

| 9 | Fayetteville Technical Community College | 1,383 |

| 10 | Fayetteville State University | 885 |

Defense industry

editThe Fayetteville area has a large and growing defense industry and was ranked in the top five areas in US for 2008, 2010, 2011 by a trade publication.[51] Eight of the ten top American defense contractors are located in the area, including Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, General Dynamics, and L-3 Communications. The city hosts Partnership for Defense Initiatives (PDI), a trade association promoting defense contractors.[52]

Arts and culture

editAn October 2023 study released by Americans for the Arts, (AFTA)[53] found that nonprofit arts and culture organizations in Fayetteville and Cumberland County created $72.2 million in total economic activity in 2022, supported over 1100 jobs, provided $44.1 million in personal income to residents and generated $9.5 million in local, state and federal tax revenue.[54] At an April 2024 event the Arts Council of Fayetteville/Cumberland County announced that arts and cultural activities drew more than 900,000 visitors to the region.[55]

Points of interest

editFestivals

editHistoric sites

edit- Cool Spring Tavern[56]

- Evans Metropolitan AME Zion Church[57]

- Ellerslie Plantation

- The first Golden Corral[58]

- Hay Street United Methodist Church[59]

- Heritage Square[60]

Libraries

editMuseums

edit- Airborne & Special Operations Museum

- Fascinate-U Children's Museum

- Museum of the Cape Fear Historical Complex[61]

Parks and recreation

editShopping

editTheaters and arenas

editClubs and organizations

editArts & Culture Organizations

edit- Arts Council of Fayetteville/Cumberland County

- Cape Fear Ballroom Dancers

- Cape Fear Botanical Garden

- Cape Fear Regional Theatre

- Cape Fear Studios

- Community Concerts

- Cool Springs Downtown District

- Cumberland Choral Arts

- Dance Theatre of Fayetteville

- Fayetteville Artists Guild

- Fayetteville Symphony Orchestra

- The Gilbert Theater

- Sweet Tea Shakespeare

- Tarheel Quilters Guild

- Umoja Group

Sports

edit| Club | Sport | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fayetteville Woodpeckers[65] | Baseball | Carolina League | Segra Stadium | 2017 | 1 |

| Fayetteville Marksmen | Ice hockey | SPHL | Crown Coliseum | 2002 | 1 |

Education

editPublic schools

editCumberland County Schools' headquarters are located in Fayetteville. CCS operates a total of 87 schools: 53 elementary schools, 16 middle schools, 15 high schools and 9 Alternative and Specialty schools, including 1 year-round classical, 1 evening academy, 1 web academy and 2 special schools. Cumberland County Schools is the fourth-largest school system in the state and 78th-largest in the country.[66]

Cumberland County Schools serves most areas of Fayetteville for grades PK-12.[67] The Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) operates public schools on Fort Liberty for PK-8, but for high school Fort Liberty students attend local public schools in their respective counties.[68]

High schools (grades 9–12)

edit- Cape Fear High School – School of Agricultural & Natural Sciences Academy (9–12)[69]

- Douglas Byrd High School – Finance Academy & Ford Partnerships for Advanced Studies (9–12)[70]

- Ezekiel Ezra "E.E." Smith High School – Academies of Math & Science and Fire Science (9–12)[71]

- Jack Britt High School – Academy of Integrated Systems of Technology and Applied Engineering (9–12)

- Pine Forest High School – Academies of Emergency Medical Science & Information Technology (9–12)

- Seventy-First High School – School of Arts (9–12)

- Terry Sanford High School – Global Studies Academy (9–12)[72]

- Westover High School – Academies of Health and Engineering (9–12)[73]

- South View High School – International Baccalaureate (9–12)

- Gray's Creek High School – Academy of Information Technology (9–12)

Specialty schools

edit- Cross Creek Early College High School (9–12)

- Cumberland International Early College High School (9–12)

- Massey Hill Classical High School (9–12)

- Cumberland Polytechnic High School (9–12)

Private schools

edit- Berean Baptist Academy (Pre-K–12)[74]

- Fayetteville Academy[75]

- Fayetteville Christian School (Pre-K–12)[76]

- Northwood Temple Academy[77]

- Village Christian Academy

- Trinity Christian School (K–12)[78]

Colleges and universities

edit- Carolina College of Biblical Studies[79]

- Manna University (formerly Grace College of Divinity)

- Fayetteville State University[80]

- Fayetteville Technical Community College[81]

- Methodist University

- Shaw University Satellite Campus

Media

editNewspapers

edit- The Fayetteville Observer[82]

- Up & Coming Weekly Local community newspaper

- The Voice

- The Fayetteville Press

- Acento Latino

- The Paraglide

Television stations

editFayetteville is part of and served by television stations in the Raleigh–Durham television market.[83]

- FayTV7 (Spectrum Channel 7) City of Fayetteville's Government Access Channel

Radio stations

edit- 88.3 FM WUAW Various Genres

- 88.7 FM WRAE Religious Music

- 89.3 FM WZRI Christian Contemporary Music

- 90.1 FM WCCE Christian Contemporary Music

- 91.1 FM WYBH Traditional Christian Music/Teaching/BBN

- 91.9 FM WFSS Public Radio

- 95.7 FM WKML Country

- 96.5 FM WFLB Classic Hits

- 98.1 FM WQSM Top 40

- 99.1 FM WZFX Mainstream Urban (Hip Hop and R&B)

- 102.3 FM WFVL Christian Contemporary/ K-Love

- 103.5 FM WRCQ Rock

- 104.5 FM WCCG Mainstream Urban (Hip Hop and R&B)

- 105.7 FM WCLN-FM Southern Gospel Music

- 106.9 FM WMGU Urban Adult Contemporary (Adult's R&B)

- 107.3 FM WKFV Contemporary Christian/K-Love

- 107.7 FM WUKS Urban Adult Contemporary (Smooth R&B)

- 640 AM WFNC News/talk

- 1230 AM WFAY Country

- 1450 AM WMRV Classic Rock

- 1490 AM WAZZ Top 40

- 1600 AM WIDU Black Gospel/Talk

Infrastructure

editMajor highways

editInterstate highways

editU.S. highways

editState highways

editOther highways

editAir transportation

editFayetteville Regional Airport is served by five regional carriers that provide daily and seasonal passenger services to three major airline hubs within the United States. An additional regional carrier and several fixed-base operators offer further services for both passenger and general aviation operations. Landmark Aviation also provides services for passenger and general aviation traffic at the Fayetteville Regional Airport.

Public transportation

editThe Fayetteville Area System of Transit (FAST) serves the Fayetteville and Spring Lake regions, with ten bus routes and two shuttle routes. FAST operates thirteen fixed bus routes within the city of Fayetteville. Service is between the hours of 5:45 am and 10:30 pm on weekdays, with reduced hours on Saturdays and no Sunday service. Most routes begin and end at the Transfer Center at 147 Old Wilmington Road in Fayetteville. Other transfer points are located at University Estates, Cross Creek Mall, Veterans Administration Medical Center, Bunce and Cliffdale Rds and Cape Fear Valley Medical Center.

Passenger rail

editThe Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Station, built in 1911, provides daily Amtrak service with northbound and southbound routes leading to points along the East Coast.[84]

Notable people

editSister city

editFayetteville has one sister city, as designated by Sister Cities International:

- Saint-Avold, Moselle, Grand Est, France[85]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Mayor Mitch Colvin breezes to re-election". Fayetteville, NC: CityView TODAY. July 27, 2022. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ a b "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Fayetteville, North Carolina

- ^ United States Census Bureau (December 29, 2022). "2020 Census Qualifying Urban Areas and Final Criteria Clarifications". Federal Register.

- ^ a b c d "QuickFacts: Fayetteville city, North Carolina". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2020-2023". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Fayetteville Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster".

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Fayetteville, North Carolina". www.carolana.com. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Marker: I-54". www.ncmarkers.com. Archived from the original on November 6, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c Encyclopedia of North Carolina, 3rd ed., Vol. 2 (1999), p. 254.

- ^ "Lafayette's Visit". NCPedia. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ "Fayetteville Observer March 10, 1825" (PDF).

- ^ "Citywide Fire in Fayetteville, 1831". This Day in North Carolina History. N.C. Department of Natural & Cultural Resources. Archived from the original on May 29, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Bell, William (1789-1865) : NC Architects & Builders : NCSU Libraries". Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ Morgan, David T. (2005). Murder Along the Cape Fear: A North Carolina Town in the Twentieth Century. Mercer University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-86554-966-1.

Rottman, Gordon L. (February 4, 2020). Grunt Slang in Vietnam: Words of the War. Casemate Publishers. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-5040-6170-4.

Fry, Joseph A. (June 19, 2015). The American South and the Vietnam War: Belligerence, Protest, and Agony in Dixie. University Press of Kentucky. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-8131-6109-9.

Baca, George (June 8, 2010). Conjuring Crisis: Racism and Civil Rights in a Southern Military City. Rutgers University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-8135-4979-8. - ^ "BRAC: Developers Place Bets on Growth"[dead link], Fayetteville Observer

- ^ "5 Star Towns for Military Retirement" (PDF). Where to Retire. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ "Cities in Danger of a Housing Crisis (Study 2019) | GOBankingRates". Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ "At 1,600 Pounds, this is officially the World's Largest Christmas Stocking". FOX News Insider. FOX News. December 11, 2015. Archived from the original on December 14, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ "Pope Army Airfield History". pope.af.mil. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ "Fort Bragg History". home.army.mil. United States Army. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ Mims, Bryan (September 16, 2008). "Bragg annexation could boost Fayetteville's retail scene". WRAL. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Fayetteville Wants You" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2011. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ Thornburgh, Nathan (November 20, 2008). "Fayetteville: America's Most Pro-Military Town". Archived from the original on April 4, 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2009 – via www.time.com.

- ^ Jacobs, Chick (April 16, 2021). "10 years ago today, deadly tornadoes struck the Fayetteville area killing 8 and injuring hundreds". The Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Fayetteville RGNL AP". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Fayetteville (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". May 7, 2015. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Fayetteville city, North Carolina". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Fayetteville city, North Carolina". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Fayetteville city, North Carolina". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ Woolverton, Paul (May 27, 2019). "People from many lands live in Fayetteville". The Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 (DP-1): Fayetteville city, North Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates (DP03): Fayetteville city, North Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ Lowrey, Michael (June 8, 2005). "Court Allows Fayetteville Annexation". Carolina Journal. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Barksdale, Andrew (March 17, 2017). "The annexation debate". The Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ "Fayetteville seeks $198M in bonds to extend utilities into annexed areas". WWAYtv3.com. October 4, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ "The Bluff Presbyterian Church". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ "The Bluff Presbyterian Church". Archived from the original on June 21, 2007.

- ^ "Discoverfayetteville.com". Archived from the original on February 3, 2007. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Fayetteville, 2844 Village Drive; Copyright 2013, NC 28304-3813. "History". St Patrick Catholic Church. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Saudi Aramco World : The Life of Omar ibn Said". archive.aramcoworld.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ "Marker: I-89". www.ncmarkers.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ Futch, Michael (October 29, 2010). "A slave and scholar, Omar Ibn Said led an exceptional life". Fayetteville Observer. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019.

- ^ "Community Facts > FACVB". Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ "Fayetteville, North Carolina Metropolitan Unemployment Rate and Total Unemployed | Department of Numbers". Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ "2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, City of Fayetteville".

- ^ "Top 5 Defense Awards 2011". Expansion Solutions Magazine. Cornett Publishing Co., Inc. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ "PDI Research & Development Lab - Mission Statement - North Carolina". Archived from the original on April 15, 2013.

- ^ "Groundbreaking Arts & Economic Prosperity 6 Study Reveals Impact of the Arts on Communities Across America". Americans for the Arts. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Meador, Stephanie (April 17, 2024). "Arts Council of Fayetteville/Cumberland County details economic impact of local arts industry". Greater Fayetteville Business Journal. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Woolverton, Paul (April 17, 2024). "Study: Cumberland arts industry generated $72.2 million of economic activity in 2022". CityView. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Woolverton, Paul (January 13, 2019). "What survived the 1831 fire?". The Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- ^ "The History of Evans Metropolitan A.M.E. Zion Church". Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "The Brand Story". Golden Corral. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "Hay Street United Methodist Church – First Time Visit". Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Heritage Square". visitFayettevilleNC.com. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "About us – Cape Fear Museum". museumofcapefear.ncdr.gov. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "Official website of Cross Creek Mall". CrossCreekMall.com. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "About Crown Complex". Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Woman's Club of Fayetteville -". Archived from the original on October 11, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ^ "Official website of the Fayetteville Woodpeckers". Minor League Baseball. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "CCS District Profile". ccs.k12.nc.us. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Cumberland County, NC" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022. - Text list - Note "Fort Bragg Schools" (UNI 00014) refers to the DoDEA situation.

- ^ "Fort Bragg/Cuba Community". Department of Defense Education Activity. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Cape Fear High School". ccs.k12.nc.us. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ "Douglas Byrd High School". ccs.k12.nc.us. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ "E.E. Smith High School". cc.k12.nc.us. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ "Terry Sanford High School". ccs.k12.nc.us. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ "Westover High School homepage". ccs.k12.nc.us. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ "Berean Baptist Academy - Fayetteville, NC". www.bbafnc.org. Archived from the original on February 18, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ "Fayetteville Academy". Archived from the original on November 21, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Fayetteville Christian School". Archived from the original on December 25, 2008. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ "Northwood Temple Academy". Archived from the original on January 3, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ "Trinity Christian School". trinitycommunityservices.org. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "Our Mission & Core values – Carolina College of Biblical Studies". ccbs.edu. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Our History – Fayetteville State University". uncfsu.edu. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Fayetteville Technical community college official website". faytechcc.edu. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "Fayetteville Observer homepage". The Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Nielsen Station Index, Viewers in Profile, Raleigh–Durham (Fayetteville), NC May 2010

- ^ "North Carolina's Rail Division with AMTRAK Service". bytrain.org. Archived from the original on November 2, 2006. Retrieved November 8, 2006.

- ^ "Interactive City Directory". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

Works cited

edit- Baca, George. Conjuring Crisis: Racism and Civil Rights in a Southern Military City (Rutgers University Press; 2010) 196 pages. An ethnographic study of urban politics and racial tensions in Fort Bragg and Fayetteville.

- Fenn, Elizabeth A.; Watson, Harry L.; Nathans, Sydney; Clayton, Thomas H.; Wood, Peter H. (2003). Joe A. Mobley (ed.). The Way We Lived in North Carolina. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Meyer, Duane (2007). The Highland Scots of North Carolina, 1732–1776. The University of Matthew Burris.

- Oates, John (1981). The story of Fayetteville and the upper Cape Fear. Fayetteville Woman's Club.